On April 16, 1746, on the moor of Culloden in Scotland, the British government army clashed with Jacobite forces. The Jacobites, led by the claimant to the throne, Charles Edward Stuart, fought to restore the Stuart dynasty to power in Britain. The better-equipped and organized Hanoverian government troops defeated them despite their courage. The Battle of Culloden ended the Jacobite rebellions in Scotland. Pursued, Charles Stuart went into hiding before exiling himself to France, while repression struck the surviving Jacobites.

What Were the Causes of the Battle of Culloden?

From 1688 to 1689, the Second English Revolution, also known as the “Glorious Revolution,” took place. Following this revolution, King James II overthrew the Stuart dynasty. The English Parliament entrusted the crown to James II’s daughter, Mary II, who ruled with her husband, William of Orange-Nassau. They were considered usurpers by supporters of James II, who had taken refuge in France. The Latin name Jacobus gave James II’s supporters the nickname Jacobites.

Primarily from Ireland and Scotland, the Jacobites aimed to restore the Stuart dynasty, of Scottish origin, and return the crown to James II. A rebellion broke out in Scotland in 1689, pitting Jacobite forces against the Orangists, resulting in a defeat for the Jacobites. James Francis Stuart, the son of James II, led the Jacobites after his death. They continued the fight and attempted to land in Scotland in 1708 and again in 1715, all of which ended in failure.

In 1744, a war broke out between France and England. Jacobite refugees in France, led by Charles Edward Stuart (son of the previous claimant), sought to take advantage of this to invade England. The country was under the control of the House of Hanover, with George II at its head. Despite the lack of an invasion, the House of Hanover launched the second Jacobite rebellion. Charles landed in Scotland in July 1745 and managed to assemble a powerful army. His troops won the battles of Prestonpans (September 1745) and Falkirk (January 1746). Ready to invade England, Charles did not receive the expected aid from France and had to remain in Scotland. In April 1746, the Jacobites took Inverness and Fort Augustus. The Hanoverian forces joined them on Culloden’s moor to confront them.

How Did the Battle of Culloden Unfold?

The Battle of Culloden took place on April 16, 1746. The two armies met on the moor of Culloden, located between Inverness and Nairn in Scotland. When the Hanoverian army arrived in Nairn, the Jacobite troops were at Drummossie, near Inverness. Since early April, Charles Edward Stuart’s supporters have had control of the city, as well as Fort Augustus, a fortified stronghold at the western end of Loch Ness. The weather conditions were poor due to rain, making the terrain marshy. Scottish General George Murray advised Charles against fighting in this location, where his soldiers would be too exposed to enemy fire, but the young claimant did not listen.

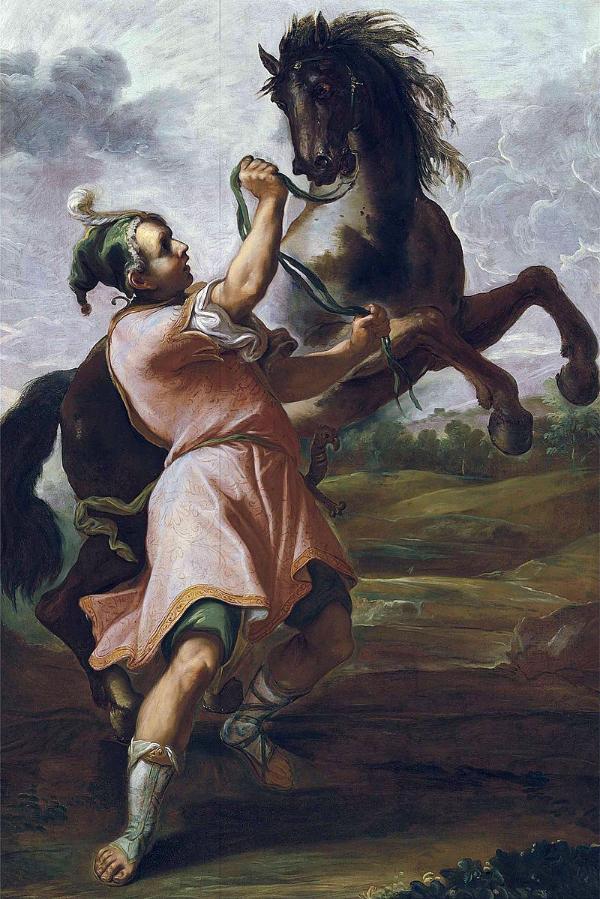

To win the battle, the Jacobites relied on the courage of the Highland warriors, armed with broadswords and axes. They planned to lure the enemy into taunting them, then defeat them with deadly charges. In contrast, the Hanoverian forces were better disciplined and equipped with powerful artillery and bayonet rifles. They used a new technique to break the momentum of the Highlanders’ charges: to render the Scottish shields ineffective, soldiers aimed their bayonets at the enemy coming from the right rather than targeting those coming directly in front.

Who Won the Battle of Culloden?

The government army, commanded by the Duke of Cumberland, won the Battle of Culloden. Better organized, the Hanoverians pounded the Jacobites with their cannons and mowed down enemy charges with shrapnel and grenades. In less than an hour, they managed to rout the Jacobite army. General Cumberland commanded the execution of the wounded and low-ranking prisoners. He also hunted down Jacobite survivors in the surrounding villages, searching barns and setting fire to houses near the battlefield.

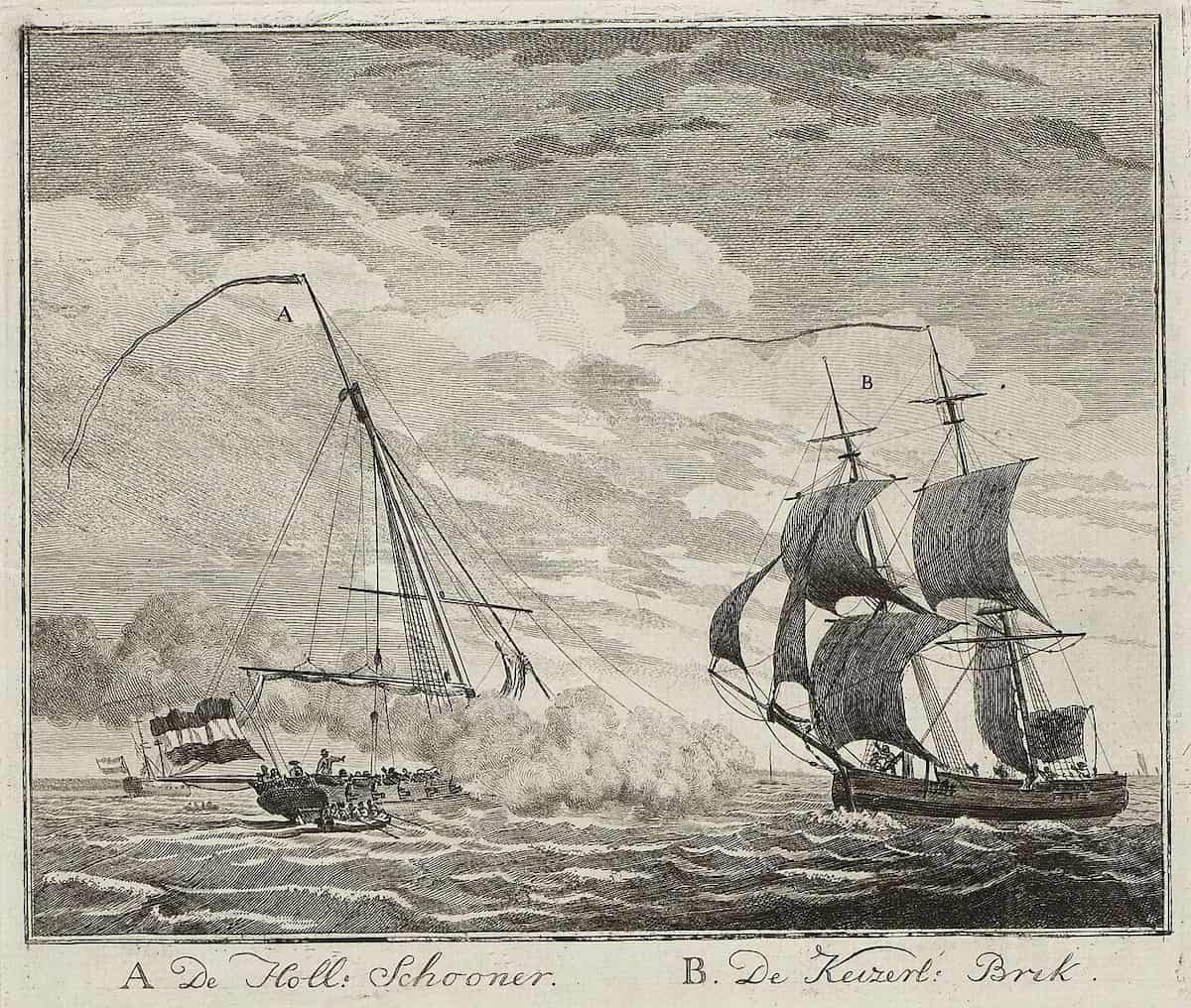

The repression resulted in tens of thousands of casualties, earning Cumberland the nickname “Butcher of Culloden.” High-ranking Jacobite prisoners faced imprisonment and trials. High treason led to the trial and execution of some officers. The government offered Charles Edward Stuart’s head as a reward. To escape his pursuers, the Jacobite leader disguised himself as a woman and hid in the western Highlands. In September 1746, he managed to board a ship that took him back to France.

Who Were the Combatants in the Battle of Culloden?

The Battle of Culloden pitted the Hanoverians against the Jacobites. The Hanoverian government army, consisting of 8,000 men, fought for King George II, the King of Great Britain. Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, one of King George II’s sons, commanded it. Its ranks included Englishmen, as well as Germans and Lowland Scots, close to England. The Jacobites, numbering 7,000, were under the command of Charles Edward Stuart and General George Murray. Charles Stuart, nicknamed “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” led the second Jacobite rebellion.

The son of James Francis Stuart and the grandson of James II, he aimed to reconquer the throne of Great Britain and restore the Stuart dynasty. The Jacobite army mainly consisted of Scottish Highlanders, Irishmen, and a few English loyal to the Stuarts, but also Scottish and Irish soldiers from the French army (the Irish Brigade). Indeed, King Louis XV of France was at war with Great Britain and unofficially supported his cousin Charles.

How Many Deaths Were There in the Battle of Culloden?

The Hanoverian camp reported only 300 deaths and wounded from the Battle of Culloden. Among the Jacobites, the toll is heavier: between 1,500 and 2,000 dead and wounded. The Hanoverians capture 3,800 Jacobite soldiers and 200 soldiers from France.

What Were the Consequences of the Battle of Culloden?

The Battle of Culloden marks the end of the Jacobite rebellions. The British government handsomely rewarded the Scottish lords who remained loyal to it. On the other hand, the Jacobite-supporting nobles lost their lands. As part of a policy to integrate Scotland into the rest of Great Britain, the government drafts laws abolishing the hereditary rights of lords and clan chiefs in the Highlands. This weakens the identity of the Highlanders and, more broadly, Gaelic culture.

In 1746, the Dress Act declared the wearing of tartan and kilt, the main elements of traditional Scottish costume, illegal. Loyal subjects of Scottish origin received the confiscated lands from the Jacobites. These individuals create large pastures for sheep farming and expel the peasants present on their lands. Many Highlanders emigrate to the Lowlands or settle in North America. We refer to these massive population movements as the “Highland Clearances.”

Charles Edward Stuart, on the other hand, takes refuge in France and converts to Protestantism, hoping one day to reign over England and Scotland. Expelled from France in 1748, he stayed in Avignon, in papal territory. In 1759, he failed to convince the French to invade Great Britain, which definitively ended his project to ascend to the throne. He settled in Italy and died in Rome in 1788, without any legitimate descendants.