The Indus culture remains the most enigmatic of the great sophisticated civilizations due to its indecipherable writing, astonishingly contemporary cities, and massive empire, the end of which is just as unknown as its commencement. Little is known about it, despite the fact that it influenced a large area about 5,000 years ago.

Many people are unaware that the Indus civilization is one of the three major early sophisticated civilizations. Indeed, little is known about these people despite the fact that their dominion was once greater than that of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia put together. The only thing we know for sure is that they had a profound impact on the whole region, which is now Pakistan, as well as on sections of India and Afghanistan, beginning approximately 2800 B.C.

The reasons for this culture’s emergence and subsequent fall, some 700 years apart, remain unknown. Also, nobody knows for sure what language the locals spoke, and nobody has been able to understand the writing, which does not seem to be connected to any of the established scripts.

The Indus civilization’s early years

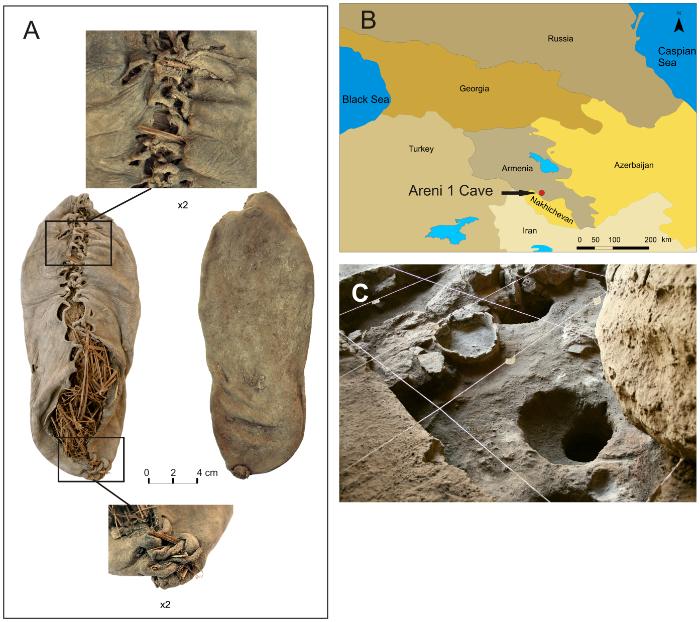

Early human settlement and the domestication of animals and plants started in the Indus River area, where Stone Age artifacts indicate people began to dwell some 10,000 years ago. They were a typical agricultural society from around 6500 B.C. forward, when they began raising cattle and growing wheat, among other crops.

At about 2600 B.C., however, everything changed. Huge cities home to thousands of people sprung up all throughout the Indus basin. Harappa and Mohenjo-daro are two of these cities that have provided archaeologists with their first glimpses of these mysterious people and their way of life.

The Indus city plans are very similar, giving the impression that they were all drawn out at the same time. Buildings and streets inside them, as shown by excavations, adhered to a rigorous geometric layout, startlingly comparable to the districts of contemporary towns. Broad avenues ran along north to south, while narrower streets intersected at right angles, much like the squares on a chessboard.

A standardized architecture

A majority of the residences in the neighborhood were large rectangles. Mohenjo-daro and Harappa had a very consistent exterior look; unlike the colossal structures typical of Mesopotamia, they were designed with functionality in mind. Not even enormous temples or palaces were built. The majority of the structures were made from burned mud bricks, and they all followed the same design: Typically, after passing through a vestibule, one would enter a courtyard that the rest of the rooms would be organized around. Some of the homes included lofts or roof decks that could be used as extra living space.

Researchers have speculated that the Indus civilization may have been the first to have advanced urban planning because of its remarkably practical, cohesive structure and design.

Water from the tap and central sewerage

Furthermore, the remainder of the infrastructure in these Bronze Age towns was remarkably advanced for its time. Mohenjo-daro, for instance, had a public bath and a central well about 4,000 years ago. Many people, however, had their own very modest wells dug into the mud brick walls of their homes in order to get potable water. Some structures may have even had running water piped in via these underground networks. According to the excavations, the sewage from the homes was carried through clay pipes into the municipal sewer system, which consisted of sewers covered with bricks and ran down the main streets.

Much of Mohenjo-daro was constructed on a plateau to prevent it from flooding, with watchtowers and fortifications along its southern side to ward off invaders. Raw materials for jewelry production and a large number of beads point to the existence of workshops in addition to residential structures in these cities. Some of these raw minerals could only be sourced from Central Asia or farther afield, indicating the sophisticated trading network that the ancient Indus society had.

Fixed units of measurement and reference weights

One such indicator of the Indus culture’s sophisticated level 4,500 years ago is its unified and astoundingly exact system of units of measurement. Buildings, plazas, and even the mud bricks themselves all seem to adhere to consistent proportions, according to surveys of Indus towns. These may all be reduced to 0.69 inches (17.6 mm), the putatively fundamental measuring unit of the Indus civilization.

Precise rules

In 2008, researchers unearthed the clay crossbeam of a scale with lines cut into it at regular intervals—every 0.69 inches—in the Indus city of Kalibangan. Subunits of this measurement, called angulam, were reportedly recognized by many smaller markings in between. It is already clear to Indus specialists that the builders at Harappa adhered to strict standards of proportion and beauty, rather than relying on chance.

Early on in the excavations at Mohenjo-daro in 1931, researchers uncovered a number of cube- and cuboid-shaped blocks of limestone of varying sizes, proving that the people of the Indus empire were also methodical when it came to weight. Extensive digging has uncovered similar blocks from other cities, each one looking like an egg next to the originals. What were they, though?

Reference weights for trade

Clues might be gleaned from the places where the blocks were unearthed, since they often turned up with artifacts associated with commerce such as seals and merchandise. These blocks have now been identified as reference weights and utilized in the commerce sector for the purpose of measuring items. The tiniest bricks weighed 0.89 grams (0.031 ounces), which is lighter than the gram unit.

Within a certain weight category, there is only roughly a 6% variation in Indus weights.

The Indus script, which has yet to be deciphered

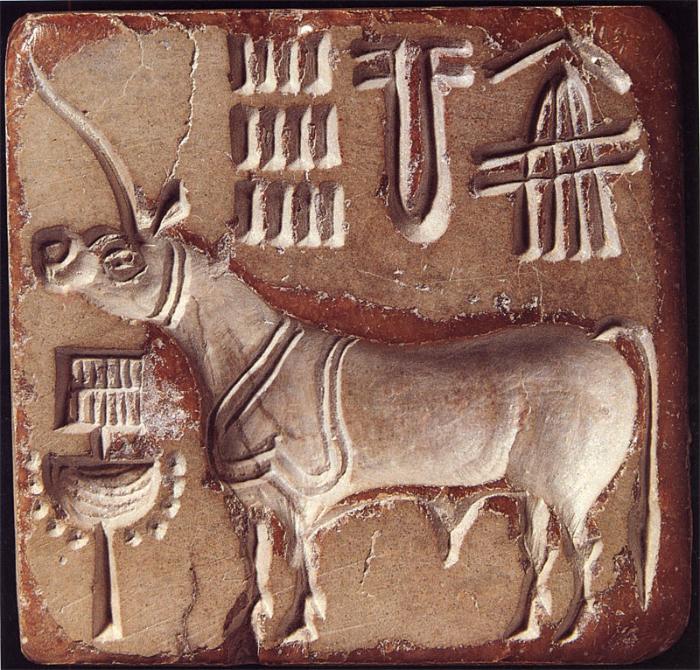

The Indus people’s writing looks like a blend between Egyptian hieroglyphics and Sumerian cuneiform, with its use of triangles, circles with cross-like letters, and plant-like symbols. Neither of those things has anything to do with it, and the meaning of its characters is still a mystery.

One explanation is that, unlike the lengthy Mesopotamian text tablets, Indus characters often occur in clusters of no more than six. They are often affixed to clay seals, miniature tablets, and talisman-like amulets. They are often mixed with animal representations, particularly on the seals.

Mysterious signs and animal symbols

It is possible that the animals’ emblems denoted certain people or clans, and that the names or legitimacy of the owners were indicated by the text. Clay jars, metal implements, and even gold jewelry have all been unearthed with the mysterious writing. Names found in that area may also date back approximately 5,000 years to the people who lived in the Indus Valley.

However, the Indus script remains as mysterious as it was when first found, despite decades of efforts to translate it. Not only is it unclear what language the strings were written in, but it’s also possible that the same script was used for more than one language. While some in the academic community are convinced that it is a genuine script, others see the symbols not for what they are, but for what they represent, such as religious or political iconography.

Mathematical aid

But Mumbai’s Tata Institute of Basic Research researcher Mayank Vahia disputes this. A few years ago, he utilized mathematics to crack the code of the puzzling characters and found evidence that they were, in fact, a legitimate script with a set canon of symbols and an underlying grammar.

The research conducted by Vahia and his coworkers is founded on the so-called Markov model, a statistical technique for forecasting the likelihood of an occurrence based on its antecedents. Insights into the Indus script’s underlying grammatical structure can be gained using the statistical approach. Any meaning attributed to a symbol during the decipherment process using such a model must be consistent with the meanings of the symbols that came before and after it.

A specific sequence

The studies verify the existence of meaning in the string of characters. If researchers randomly switched characters in their model or transplanted a hieroglyph from one set of characters to a sequence on another artifact, the likelihood of the new sequence matching the predicted language and its patterns dropped quickly. These findings provide more evidence that Indus writing follows a consistent set of rules.

It seems to be adaptable as well. Given that seals with sequences of these characters have been uncovered in both the Indus and Mesopotamian regions. However, the signs there are ordered differently from those from the Indus Valley, suggesting that the identical symbol sequences may have had a distinct meaning in that region. The possibility that the Indus script may have been used to express a variety of themes in western Asia is an intriguing finding. The concept that the hieroglyphs were only religious or political symbols is hard to square with the available evidence.

The meaning of the mysterious symbols, and whether or not they represent actual writing, are still mysteries. In this case, archaeologists and linguists are banking on luck in the shape of fresh discoveries that may provide more insight. Nothing will be certain until a multilingual tablet, a type of Indus Rosetta Stone, is discovered.

How peaceful was Indus Valley Civilization?

Archaeological digs in the town remnants have uncovered no indications of conflict or violence, neither in the destruction of structures nor in combat scenes on art items or pottery, which has long been one of the most remarkable elements of the mysterious Indus civilization. No signs of a superior or subordinate caste or a governing elite were to be found.

Therefore, it was theorized that the Indus civilization was structured more like a “grassroots government,” in which the populace gave political and religious leaders little power and the social order was relatively flat. As a result, it was assumed that very little physical force was required to maintain order in society.

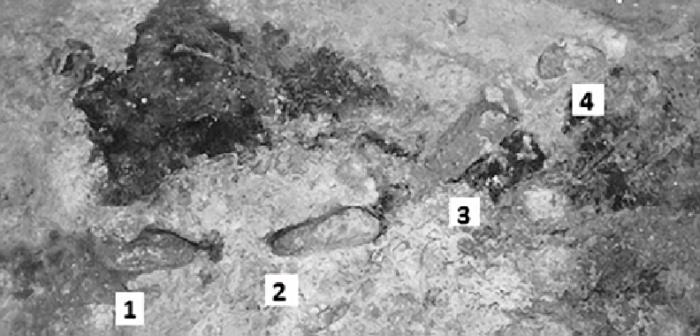

However, throughout the summer of 2012, archaeologists discovered objects that broke, or at least severely rattled, the picture of the empire as a place of peace. 160 corpses from three Harappan tombs were analyzed by a team of experts headed by Gwen Robbins Schug of Appalachian State University in Boone. Numerous traces of severe injuries were discovered, most notably in bones dating to the late Indus civilization era (ca. 1900–1700 BC).

Signs of beatings and fightings

15 percent or more of the skulls in a tomb from this time period showed signs of violence, such as cracks or fractures in the top of the skull from a hit from a blunt weapon or other damage to the bones. A male in his mid-30s had a broken nose and a cut across his forehead from a sharp weapon, and a lady had been battered to death, judging by the fractured skull.

The skull trauma does not seem to have resulted from an accident or to be consistent with postmortem trauma. Experts say the evidence points inexorably to violent interactions between people. They claim that women and children were disproportionately affected by such violence at that period. The researchers concluded that the level of violence in Harappa was very high, even by city standards, and was the highest of any Southeast Asian region at the time. That begs the question, why?

Turmoil and violence

By comparing them to tombs and corpses from previous eras of the Indus civilization, researchers were able to deduce that signs of violence were, in fact, exceedingly uncommon. It seems that murder and manslaughter were very rare even when Harappa had more than 30,000 residents. However, something shifted about 1900 B.C., and the Indus civilization started to crumble.

This era was a time of social upheaval all throughout the known world, as many towns were abandoned and people moved out of the countryside. The rise in hostility and violence may be traced back to this period of change and the stress and uncertainty it produced among the populace.

The inhabitants of Harappa’s metropolis clearly experienced regular bouts of war and hardship. This shows that, at least during this time period, the Indus Empire was not a very peaceful one.

What caused the demise of the Indus Valley Civilization?

The fall of the Indus civilization is baffling, as is the fall of many other early great civilizations. Why did this civilization, which once occupied 390,000 square miles (1 million square km) and accounted for up to 10 percent of the world’s population, go away over time? What caused people to abandon the Indus Valley’s major cities and, in many cases, the whole area after 700 years?

There are many proposed explanations for this mystery, but there are only a few solid pieces of evidence. Social upheaval, invasions by neighboring peoples, and a reduction in commerce are all possible explanations that have been proposed by some experts. While some believe that internal strife or external threats to civilization led to its demise, others point to the weather as the likely culprit.

Floods and dry seasons

The Indus Valley and its tributaries were very fertile at the period of the Indus culture, providing abundant opportunities for proper agriculture to feed even bigger towns. Nonetheless, the glacial meltwater from the Himalayas and a considerably less predictable factor: the monsoon, were responsible for this fertile soil and water supply.

In the upstream areas, near the rivers’ sources, the rain was heaviest during the wet season. This water then rolled down the rivers again, generating floods, as it does to this day in Bangladesh and Pakistan, in the form of flash floods and high tides. As was the case with the Nile at the same time, the fertile soil along the riverbanks was made possible by the river’s periodic flooding.

However, unlike ancient Egyptians and even Mesopotamian societies, those who lived in the Indus Valley reportedly didn’t try to manage and regulate these floods by means of irrigation systems. A traditional irrigation farming system has not left any traces that we can find. Could this have been the beginning of the downfall?

Did the monsoon contribute to the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization?

How did weather contribute to the demise of the Indus civilization? After all, other sophisticated cultures like the Maya and the Khmer Empire at Angkor Wat fell victim to dry seasons, too. In fact, in 2012, researchers uncovered Indus culture-related data supporting the same thing.

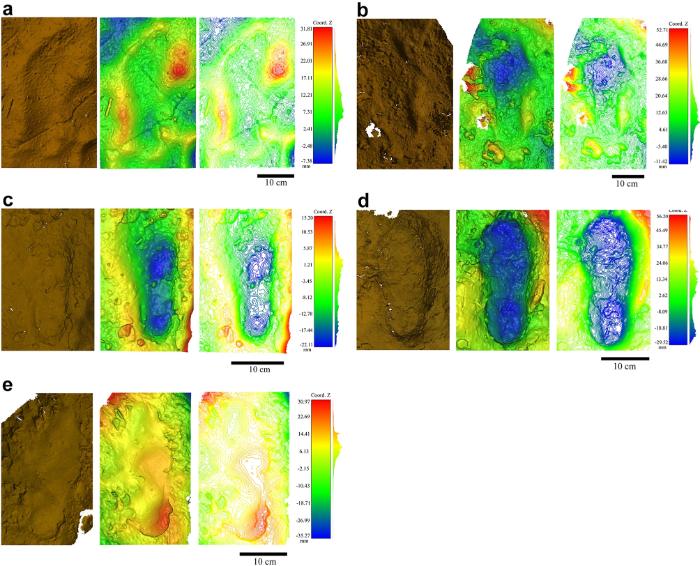

The researchers began by developing a computerized topography model of the Indus Valley, which was done by Liviu Giosan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and his colleagues. The researchers dug pits and sifted through the silt to piece together the history of the region and the river movements within it. University College London co-author Dorian Fuller discusses how the discovery of this geological data allowed the team to integrate prior knowledge of Indus communities, climate, and agricultural practices.

Climate-friendly, at least initially

The results of the analysis showed that the climate had a major impact on the development of the Indus civilization. Several centuries passed before the first settlements were established in this area, and the environment gradually became drier as a result. The researchers estimate that the height of this dry era occurred about 3200 B.C., which is also when the Indus civilization started to develop.

They believe this is not a coincidence, since climatic change during this period reduced the severity of flash floods along the Indus and its tributaries, but still caused sufficient flooding to enrich the soil in the areas close to the rivers. In particular, the fertile soil and plentiful water supply in the plains where the Indus meets its three connected tributaries—the Jhelum, the Chenab, and the Ravi—made for abundant crops.

Harappa, too, called this place home, since it was nestled within a chain of hills not far from the river’s lush floodplains. Further to the northeast, in the Ghaggar-Hakra river system’s basin, a second population center emerged. The monsoon rains were the primary supply of water for these rivers, not the melting snow. That’s why experts say there weren’t any devastating spring floods, but there was plenty of water throughout the rainy season.

The Himalayas provide a safe haven

Unfortunately, this paradise did not endure. Actually, the drought became much worse. As the monsoon moved east, the Ganges area began receiving more precipitation than the Indus basin. Around 1900 B.C., the Indus River and its tributaries became less prone to catastrophic floods, and large swaths of the southern Ghaggar-Hakra river system were without water for months at a time.

“The expansion of Indus Civilization-era communities near the Ghaggar-Hakra system’s birthplace can also be explained by this,” Giosan says. It’s because even at the foot of the Himalayas, there were still modest floods that permitted at least one harvest a year. However, this repeated climatic change proved disastrous for the tens of thousands of people living in the lowlands’ megacities. As a result, the fields’ ability to provide for the ever-increasing food needs of the populace was severely compromised by the arid weather.

Time to emigrate

If water was becoming more limited, then why didn’t the people of Harappa and the other settlements at least create an irrigation system? Because they could have done something far less difficult. The people of the Indus were able to expand into the wetter lands to the east, towards the Ganges River, whereas the people of Mesopotamia and Egypt were hemmed in by deserts and arid plains. Nonetheless, this movement reduced the overall population density in the Indus Valley.

As the water supply dwindled, people increasingly stopped living in cities and instead settled in smaller communities. It’s likely that society at the time was particularly susceptible to various forms of disruption because of the severity with which the environment had changed. But even this doesn’t explain all that went wrong with the Indus civilization in a single, deterministic explanation. Therefore, it is still not officially known what caused the Indus civilization to collapse.