Combat between German and French forces at Verdun raged from February 21 to December 18, 1916. The Germans launched an assault meant to “bleed the French army dry.” In short order, General Pétain was given responsibility for defending this section of the front, and he organized the front’s supply by building the “sacred way,” a road that was widened and maintained to allow two lines of trucks to pass each other without stopping. French resistance forces were able to slow the German advance, but at an unbelievable cost in lives and injuries. France’s victorious offensive at Verdun was widely regarded as a turning point in World War I (1914–1918).

Why Was the Battle of Verdun Fought?

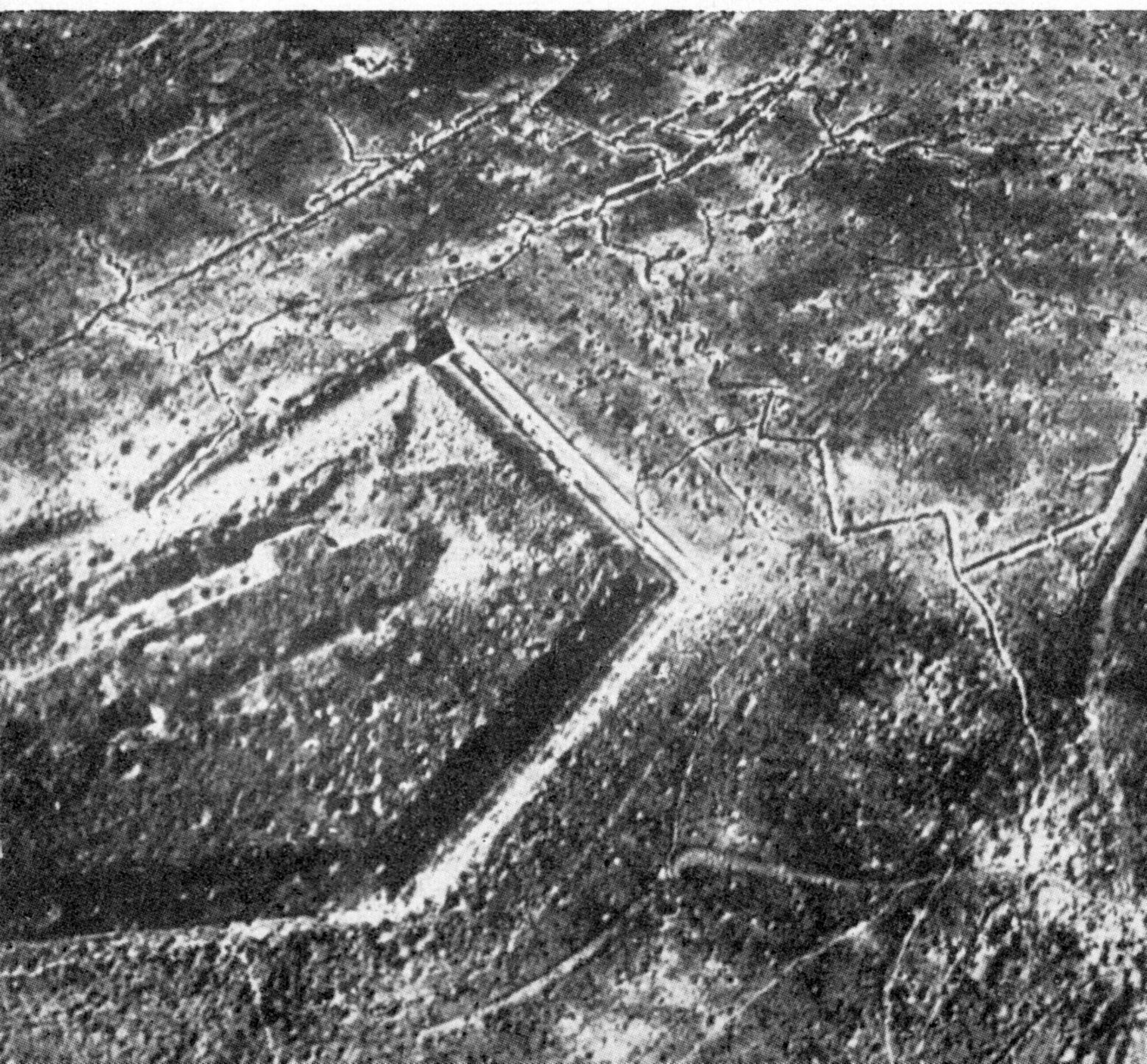

Since the Battle of the Marne, the war of movement had been transformed into a war of positions: the combatants buried themselves in trenches, fought in horrible conditions, folded in the mud in the midst of rats, were surrounded by corpses that were not always possible to evacuate, and above all, survived in fear. General Erich von Falkenhayn planned to “bleed the French army white” on the Verdun salient with the fire of thousands of cannons, meaning to exhaust it both morally and physically before completely defeating it. The Kronprinz, William II’s eldest son, who was also intent on destroying the French army and who described Verdun as the symbolic “heart of France,” backed him up in this mission.

The location on the Meuse in Lorraine and its fortifications made it a strategic issue and a matter of national honor for the French, and the Germans knew this. The military history of Verdun’s defense was extensive, beginning with the construction of fortifications in the 14th century and continuing with the construction of an underground citadel under Louis XIII, its consolidation under Louis XIV with Sebastien Le Prestre de Vauban, and its reinforcement once more at the end of the 19th century. The Prussians besieged and conquered the city twice: in 1792 and again in 1870.

Due to the salient in the front and the dividing Meuse River, Verdun was a very difficult battlefield to defend. The Germans were also aware of the difficulty the French would have in reaching the Verdun-based troops due to the lack of a proper railway line.

Since Joffre believed the Verdun defenses to be nearly invulnerable, he failed to adequately staff the forts with sufficient numbers of men and equip them with adequate weapons. Also, in August 1915, military leaders decided to relocate around forty heavy batteries and twelve field batteries to safer areas. A battle in Champagne was expected, so the outbreak of fighting at Verdun came as a shock to the French.

A Meticulously Prepared Offensive

The German high command had decided in December 1915 that Verdun would be a decisive battle, and they had prepared for it accordingly. German forces were increased from six to eight divisions, and concrete tunnels were constructed as close as possible to the French positions. The German army was spread out over a dozen-kilometer-long front, and 221 artillery batteries were set up to support them. These plans were kept secret, but the French intelligence services were aware of an attack on February 11. Although some reinforcements were dispatched to the site just in case, military authorities didn’t put much stock in this unexpected information. The assault was delayed for a few days due to bad weather.

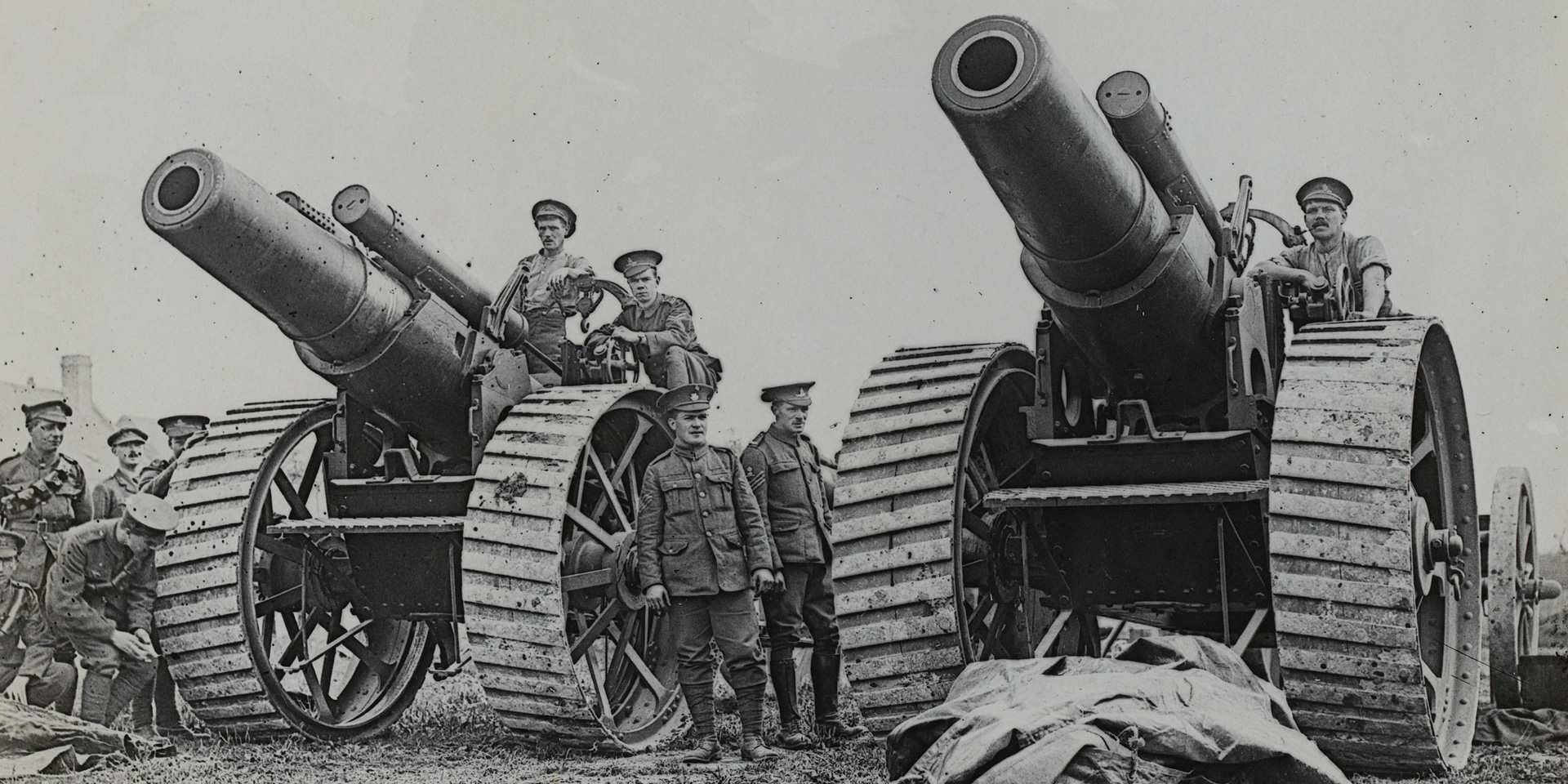

A German artillery barrage began at 7:30 a.m. on February 21. It had over 1.2 million cannons, including 13 mighty 420-mm Krupps. Bombs rained down on the three French divisions that were stationed along this fifteen-kilometer front. With only 65 artillery batteries and 270 cannons, von Falkenhayn planned to wipe out as much of the enemy infantry as possible. After nine hours of bombardments, German artillery finally gave way to infantry: German infantrymen launched themselves against French positions, and, for the first time, the formidable weapon of the flamethrower was used.

Two million shells were fired at French positions in the first 48 hours of the war, and the French front was pushed back about ten kilometers in that time. German artillery was relentless, but the French defenders’ tenacity in the face of isolation and a lack of leadership surprised the occupiers. Joffre ordered the French to resist at all costs, declaring with resolve, “They will not pass!” on February 25, after the French had lost 20,000 men and the fort of Douaumont had fallen. In order to defend Verdun, he put General Philippe Pétain in charge, with support from Generals Nivelle and Mangin of the 2nd army.

Pétain Organized the Defense

Pétain had a plan to close the gap the enemy had left and establish communication with the rear starting on February 26. Over the course of 24 hours, reinforcements and supplies of food and ammunition were brought in via the 6,000 trucks that took the “sacred road” connecting Bar-le-Duc and Verdun. They brought back a lot of wounded soldiers when they got home. From that point on, weekly transports included 90,000 men and 50,000 tons of equipment. Additionally, Pétain established a rotation of units that led to two-thirds of the French army taking part in the fighting at Verdun in an effort to minimize losses within each division and provide some respite for the poilus in the area around Bar-le-Duc.

The French army grew from 230,000 to 584,000 strong between February and April, with the artillery nearing 2,000 pieces, of which a quarter were heavy weapons. But the Germans continued to show their strength; on February 27, they captured the fort of Douaumont, which had been defended by only 60 men. The Germans launched their attack on the left bank of the Meuse on March 6 and quickly gained control of Cumières Wood on March 7, Mort-Homme Ridge on March 14, and Hill 304 on May 24.

The German offensive launched in the early spring was repelled on both the eastern and western fronts, and by the end of March, the enemy’s breach had been sealed. Despite the initial setback on April 9, the Germans rallied quickly, and General Mangin was unable to retake Douaumont between May 22 and May 24. Massive casualties were sustained in the so-called “hell of Verdun,” but the war of attrition nonetheless continued. The Germans captured Vaux Fort on June 7, and at the month’s end, they launched a fresh assault on Thiaumont, Fleury, and the area around Froi-deterre.

The Germans advanced three kilometers, endangering French positions on the right bank of the Meuse, and the terrible phosgene bombs made their first appearance. But the situation on the Somme, further north, gradually shifted the balance of power; on July 1, the French and British forces launched a massive offensive that compelled the Germans to reduce their numbers in Verdun in order to hold their positions on the Somme.

The Battle of Verdun Turns to the Advantage of the French

On July 11, the Kronprinz attempted a fresh assault on the fort of Souville in Verdun, but the French artillery response and counterattacks saved the situation just in time. In light of the setbacks suffered by the German forces, Marshal Hindenburg, aided once more by General Ludendorff, relieved General von Falkenhayn of his command on August 29, 1916.

General Robert Nivelle, who had replaced General Pétain as head of the 2nd Army (Pétain was given command of the Army Group Centre), began a counteroffensive against Verdun on the 24th. After losing ground steadily since February, this allowed the Allies to turn the tide and recover quickly, retaking the forts of Douaumont and Vaux within a matter of hours and two months, respectively. Along the right bank of the Meuse, between Champneuville and Bezonvaux, the front had steadied.

The French triumphed at Verdun on December 18, 1916.

The “Massacre” of Verdun

Considering the previous ten months of bloodshed and 37 million shells fired, this victory was monumental. Despite nearly 380,000 dead, missing, and wounded, France maintained its advantage in the Verdun region. It was a double loss for Germany: first, they were unable to break through the French front, and second, their casualty count (estimated at 335,000 killed, missing, and wounded) was nearly as high as France’s. After the Somme, the Battle of Verdun was the bloodiest in World War I.

KEY DATES OF THE BATTLE OF VERDUN

- German forces stormed and captured Douaumont Fort on February 25, 1916. General Pétain was given control of the fortified Verdun area after the French army suffered this symbolic defeat.

- The Germans made a small gain for their efforts on April 9, 1916, when they captured the Mort-Homme observation point. General Pétain issued a historic rallying cry the following day: “Courage, we will get them!”

- On May 1, 1916, General Joffre appointed General Nivelle to replace Pétain because Joffre found Nivelle more offensive than Pétain.

- On May 22, 23, and 24, 1916, General Mangin, acting on orders from General Nivelle, led a major French offensive that ultimately failed to retake the Fort of Douaumont. No adequate artillery preparations were made.

- On June 7, 1916, the defenders of Vaux Fort signed a document surrendering the fort. When they realized they wouldn’t have enough water to make it, the local troops under Major Raynal’s command surrendered. The Germans took control of the area.

- Following a nonstop barrage of poison gas shells on June 23, 1916, 60,000 German soldiers attacked along a 6-kilometer front. Fleury was taken. Despite this, Germany’s efforts to capture Verdun persisted in failing, producing disappointing results despite the enormous effort.

- The German army’s final offensive began in the Souville sector on July 12, 1916. There was no success. The enemy’s greatest advance during the Battle of Verdun occurred here. This was yet another setback for Kronprinz Wilhelm of Prussia’s troops, who had been told to stick to defensive measures.

- After months of planning the “artillery fire” phase, the French forces successfully retook Fort Douaumont from the Germans on October 24, 1916, effectively ending the Battle of Verdun.

Battle of Verdun at a Glance

What was the Battle of Verdun?

The Battle of Verdun was a major battle fought between German and French forces during World War I. It was one of the longest and deadliest battles of the war and took place in and around the city of Verdun in northeastern France.

What was the significance of the Battle of Verdun?

The Battle of Verdun is considered significant because it became a symbol of the tenacity and resilience of the French forces. It also represented a turning point in the war, with both sides suffering heavy casualties and the battle ultimately resulting in a stalemate.

What were the objectives of the German offensive?

The German objective was to capture the strategic city of Verdun and inflict heavy casualties on the French army, hoping to break their morale and force them to divert resources from other parts of the front.

What was Falkenhayn’s strategy in the Battle of Verdun?

German General Erich von Falkenhayn’s strategy was to engage the French in a battle of attrition at Verdun, hoping to bleed the French army and force them to commit significant resources to defend the area. His intention was to wear down French morale and create a favorable situation for German victory elsewhere

What role did trench warfare play in the Battle of Verdun?

Trench warfare was a defining characteristic of the Battle of Verdun. Both sides constructed extensive networks of trenches, which served as defensive lines and provided protection from enemy fire. The battle involved fierce fighting over small sections of land between the opposing trench systems.

Bibliography:

- Martin, W. (2001). Verdun 1916. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-993-5.

- Windrow, M. (2004). The Last Valley: The Battle of Dien Bien Phu. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84671-0.

- Horne, A. (2007) [1962]. The Price of Glory: Verdun 1916 (pbk. repr. Penguin ed.). London. ISBN 978-0-14-193752-6.

- Grant, R. G. (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey through 5,000 Years of Combat. London: Dorling Kindersley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4053-1100-7.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2014). The French Army and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60568-8.