Fordite, often known as “Ford stone,” is an artificial mineral made by layering and hardening automotive enamel paint. Detroit agate, also known as Motor City agate, is a kind of agate mined from the site of a defunct car plant in Detroit, Michigan, United States. “Fordite” was so named because it was first found in the 1940s at the Ford Motor Company’s car painting facility in Michigan. However, that automaker wasn’t the only one that produced it. Today, they are still considered an “ore,” and the raw Fordites continue to rise in value.

History and Formation of Fordite

Automobiles were once painted by hand or sprayed with a spray gun which was invented in 1888 in the United States. Therefore, the work site’s hallways, spray booths, and loading platforms were contaminated with oversprayed paint in those automotive factories.

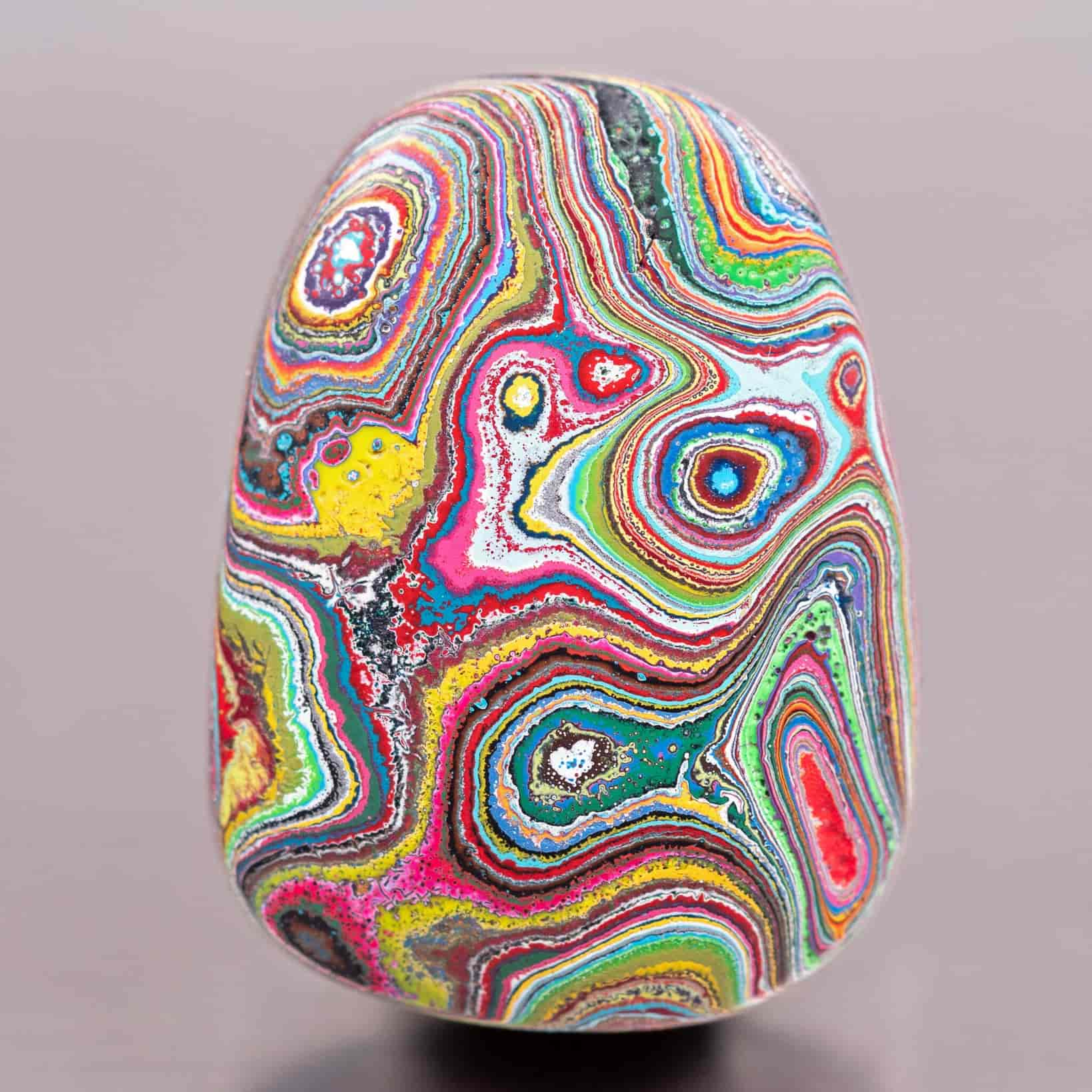

Since automobiles were often painted in highly vivid colors in the 1960s and 1970s, the Fordites from those decades tend to have more vibrant, psychedelic hues. A cabochon of a very uncommon kind of Fordite, with big metal flakes, dating from 1972, sold for $400.

Among the sources of factories for Fordite are the Corvette Assembly Plant in Kentucky, the Ford Motor Company in Michigan, the Harley-Davidson motorcycle plants, and the Lincoln-Mercury painting plant in Canada. The Fordites from the latter plant even hold a specific name: “corvetteite”.

This practice continued from the 1930s all the way to the 1990s. And as the years accumulated, the factories were covered in a rainbow of paint hues.

Since the paint was subjected to high heat treatment hundreds, if not thousands of times, the accumulated layers of paint became harder over time.

This paint buildup got too thick over time and needed to be scraped away since it was getting in the way. Some creative souls in Henry Ford‘s Ford automotive factory then realized that this layer of paint could be sliced and polished to create a beautiful agate-like gemstone, cabochons, and beads, which could then be recycled and sold as eco-friendly jewelry.

The finished product was visually spectacular and distinctive, with swirls and patterns in vivid colors that emphasized the industry’s long and storied past in automobile production.

Fordite is a Time Capsule

The color of Fordite, and, by extension, the development of the automotive industry in the United States can be deduced from its distinctive color.

According to Fordite, for instance, most automobiles in the nation in the 1940s were painted in black or brown enamel—industrial paint that dries to a very hard, glossy finish—but by the 1960s, brighter lacquers were in favor.

Current automobiles are painted with electrostatic coatings that adsorb paint granules to the steel plate by Coulomb force, or “electrostatic force”, almost eliminating the need for unnecessary spraying.

Consequently, the formation of Fordite has halted since powder painting has been replaced by hand spraying.

That’s why we no longer see new Fordites around, and the raw ones that are still around continue to rise in value. There is actually a small market for Fordites today.

What Makes Fordite Valuable?

Fordite is prized for its one-of-a-kind, multicolored patterns that have developed through many years of paint overspray accumulation. This artificial ore is actually quite uncommon because the majority of car companies no longer produce it.

Fordite finds its most widespread use in the jewelry and automobile industries. Collectors and those with an interest in automobiles often buy them.

Experienced cutters can bring out striking layers of color and design in polished Fordite. Paint is a fairly light substance because of its composition. During the cutting and polishing procedures, safety equipment like a dust mask is required.

Similarly, several generations of Jackson Whites in Sloatsburg, New York fell victim to this same paint when contractors hired by the defunct Ford factory in Mahwah, New Jersey dumped poisonous vehicle paint waste dangerously close to the communities’ houses.

Where Can I Find Fordite?

Today, Fordite is a very uncommon man-made mineral. But you may be able to find some residual Fordite in a few classic automobile assembly plants in the Detroit region. However, internet vendors and gem and mineral exhibitions are the most typical places to find Fordites.

Fordite is a colorful tribute to the American workers whose creativity and resourcefulness transformed a byproduct of the auto industry into a piece of art. The workers at the American auto factories saw value where most others would see waste, much like how older vehicles have long been admired for their beautiful looks.

Types of Fordite

There are four types of Fordite today:

- Type 1: Characterized by consistent gray banding of primer layers in between distinct color layers (Color on Color).

- Type 2: Opaques and metallics make up Type 2. Lacking variety. Miniature quantities and limited-edition colors (Distinct Colors).

- Type 3: Drippy and/or striped, with several overlapping layers of solid colors and metallic accents define this type. Patterns of lace and orbits appear on the surface, and there is some channeling on occasion (Distinct Colors).

- Type 4: Opaques and metallics of Type 4 have color layers that flow into one another and may have pitting from air bubbles that developed while the layers solidified (Distinct Colors).

Fordite at a Glance

What is Fordite?

Fordite, also known as Detroit Agate or Motor Agate, is an artificial substance made out of enamel paint layers that collected over decades on the tracks, racks, and floors of paint booths in automobile plants.

How is Fordite formed?

Layers of paint overspray would accumulate on the walls and floors of paint booths at auto assembly plants, eventually transforming into Fordite. As more paint was sprayed on top, the previous coats would dry and solidify. This method would result in thick layers of multicolored, patterned material that could be gathered and fashioned into a wide range of objects.

What makes Fordite special?

The distinctive and vibrant patterns of Fordite are the product of years of paint overspray accumulation. Since the majority of automakers no longer produce it, it is an uncommon item.

References

- Featured Image: Photography by Elaine Sweeney. Original Image – Flickr

- Relics: A History of the World Told in 133 Objects – By Jamie Grove, Max Grove, Mini Museum · 2021- Google Books

- The Ford Industries; Facts about the Ford Motor Company and Its Subsidiaries – By Ford Motor Company · 1927- Google Books