This Article at a Glance

Nittel Nacht, also known as “Christmas Night” or “Blind Night” in Yiddish, refers to Christmas Eve in Ashkenazi Jewish communities. During this time, especially among Hasidic Jews, the tradition is to refrain from studying the Torah, which may be traced back to the medieval Latin term “Natale Domini,” meaning “the birth of the Lord.” Various practices have emerged around Nittel Nacht, such as abstaining from Torah study, avoiding public activities, and engaging in specific customs to subtly express disdain for the Christian holiday of Christmas and the birth of Jesus. The origins of the name and the tradition are varied, braided with historical events, apologetic stances, and coded language. Despite its complex origins, some Jewish communities continue to observe Nittel Nacht today.

Nittel Nacht (Yiddish: “Christmas Night” or “Blind Night”) is the term used to refer to Christmas Eve in the Jewish communities of Ashkenazi descent. They also call this day simply “Nittel” or “Nitel,” and it is customary for Jews, especially Hasidic Jews, to not study the Torah on this evening. This practice may be traced back to medieval Latin, notably “Natale Domini,” which means “the birth of the Lord,” and in this sense, “Nittel Nacht” also means “night (of the holiday) of the birth.”

The Harsh Practices Associated with Nittel Nacht

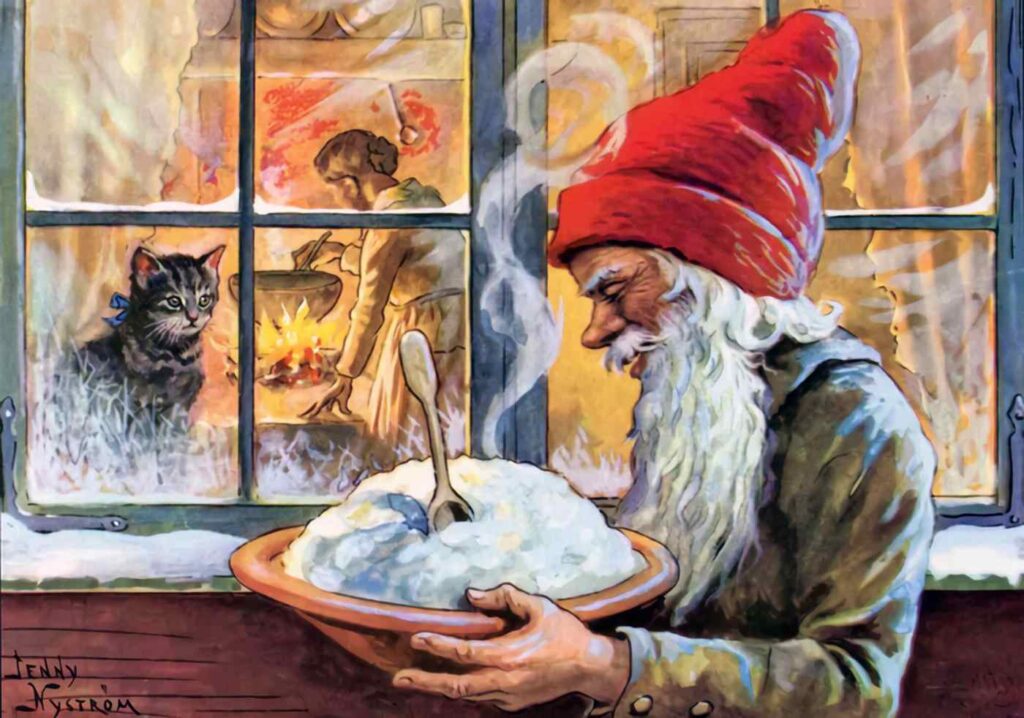

Nittel Nacht is celebrated in a number of different ways by different groups but is most widely associated with the Hasidic communities of Eastern Europe and Hungary. On Christmas Eve, the fundamental tradition is to abstain from studying the Torah from sundown until midnight. German rabbi Moses Sofer’s students often went to bed early and came back to work after midnight. Another practice includes speaking aloud the part of the prayer known as “Aleinu” that asks God to forgive those “who bow down to vanity and emptiness,” which was formerly said in hushed tones to spare the feelings of Christians.

Some Hasidic groups provide regular gatherings where members may learn about secular issues, play chess, or share a friendly game of cards. The Mertzdorf Hasidic group has a tradition of cooking items with a particularly offensive smell as a way of subtly displaying their disdain. One of the Gur Hasidim leaders used to tear toilet paper into strips and use them all year as a sign of the group’s stance against the Jewish Christian faith.

According to legend, Solomon Luria, a famous Polish Jewish scholar, used this night to tithe, or donate 10% of his income and expenditures, to good causes. Nittel is used by a large number of individuals to perform a wide range of administrative, organizational, and domestic duties. Some people would spend hours a day reading biographies of saints. Some Hasidic groups also observe the sabbath by immersing in a ceremonial bath (mikveh), fulfilling the requirement of “Onah” (marital relations), and refraining from being married on this night.

The Book of the Tales of Jesus, a “humorous” depiction of Jesus’ life written in Hebrew in the early Middle Ages and later translated into Yiddish, is read in certain communities on this day. Furthermore, in the 19th century, the “Megillat Nittel” (Nittel Scroll) appeared, which recounts the events of Jesus’ life and is said to have been written by one of Moses Sofer’s students from materials he discovered in his teacher’s possession.

Some celebrate both “Nittel Gadol” (Big Nittel) and “Nittel Katan” (Small Nittel), both on the evening of the Western Christmas (December 24) and on the evening of the Eastern Christmas (January 6, also known as “Second Christmas”). Hasidim who “choose” between the two Christmas dates often follow the Christian tradition that is more widely observed in their nation. As an added bonus, some Hasidic courtyards celebrate Nittel on January 5 from midday to midnight.

Nittel Nacht in History

Annotations to the Austro-Hungarian historian Isaac Tyrnau’s “Book of Customs” from the 14th century provide the earliest evidence of the practices associated with Nittel Nacht; in them, the custom of reciting the prayer “Aleinu” aloud on this night is mentioned, along with the phrase “who bow down to vanity and emptiness,” which is avoided during the rest of the year out of respect for the Christian community. A notable 17th-century German Jew, Yair Bacharach, first documented the practice of halting study on a certain festival night. As for the name “Nittel,” he said, “Lest a Capricorn be swallowed between seventy lions, we do not count on a miracle.”

The Mishnah’s tractate Avodah Zarah in Talmud states that “three days before their (idolaters’) holidays, it is forbidden to engage in commerce with them, borrow from them, lend to them, repay debts to them, or demand repayment from them.”

According to the Mishnah, these celebrations were known as “Kalenda, Saturnalia, and Kratisim, the day of their king’s birth and the day of his death (Genusia).” Kalenda and Saturnalia, two winter solstices observed in ancient Europe and recorded in the Mishnah, had an early impact on the development of Christmas celebrations. These well-known celebrations were included in Christian rituals as a means of attracting new members.

Commenting on the Mishnah, Italian rabbi Obadiah of Bertinoro (1450–1516) stated, “It is forbidden to engage in commerce with Christians every Sunday, and also on their holidays when they celebrate, such as Nittel and Peshkva, but their other idolatrous days, which they observe for their holy beings where divinity is not invoked, are permissible.”

In 1616, the anti-Semitic polemicist Dietrich Schwaab testified about the distorted custom in his book “The Jewish Mask” (Jüdischer Deckmantel):

“While we Christians, according to our ancient and beautiful custom, celebrate with great honor, with ringing bells, in prayer, singing, and gratitude… and the Jews hear the ringing bells, they utter words of mockery… He is here, to instill fear in the hearts of the children and the rest of the household, to the point where they do not want to go to the restroom unless they have a great need… Likewise, they do not permit themselves to study or pray on the night of Christmas, which they call ‘Nittel,’ meaning the holiday of hanging. The reason for this is that they believe that on this night, Jesus is in terrible agony, and by preventing study and prayer, he will not find peace and tranquility. Therefore, they prefer to sit idle, curse, and mock him.”

Why Jews Don’t Study Torah on Nittel Nacht

The grieving for the birth of Jesus is the reason why Torah study is forbidden on Nittel Nacht, according to a 17th-century rabbi from Karlsruhe named Nathaniel Weil. Moses Sofer, on the other hand, disputes the mourning justification, maintaining that one may engage in permitted study at any time, regardless of whether it is before or after midnight. According to him, this means that the restriction against studying the Torah is designed to silence academics. To prevent a scenario where Jews are asleep when Christians are up, they will retire to bed early at night owing to their lack of activity and wake up at midnight when the Christians rise for their prayers.

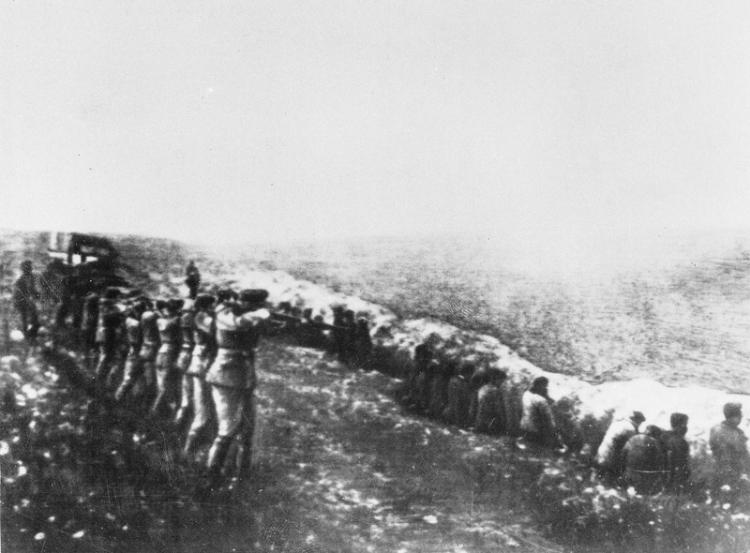

An explanation ascribed to the French rabbi Rashi’s book “Likutei HaPardes” is referenced in the late 19th-century book “Ta’amei HaMinhagim VeMekorei HaDinim,” which states that on Christmas Eve, disruptions and assaults on Jews who ventured out into the streets were widespread. This clarification does not occur in Rashi’s “Likutei HaPardes,” although its likely exclusion was owing to book burnings or other forms of censorship that targeted Hebrew texts.

This account of the origin of the tradition has been adopted by several scholars. On the other hand, critics say the risk rationale isn’t credible since education could continue in the comfort of one’s own home and there’s no proof that public prayer was suspended. The rabbis’ apologetic and contradictory stance against Christians’ assertions that Jews do not study the Torah in order to disrupt Jesus’ peace might be a manifestation of their fear of their Christian surroundings.

An example of this can be seen in the correspondence between the Jewish book censor in Prague, Karl Fischer, and Bohemian rabbi Elazar Fleckeles (1754–1826), who attempts to dismiss the questioner’s opinion by belittling certain customs and offering convoluted explanations about the origin of the term “Nittel.” The rationales from the realms of mysticism and Kabbalah refer to the night being considered impure due to the birth of Jesus, and special impure forces are attributed to that night.

The 9th of Tevet, which is quite near Christmas, is listed as a fast day on a list of around 20 days of sorrow that was transmitted from the book “Halachot Gedolot” to the “Shulchan Aruch”. But unlike the other days on the list, no clear explanation is given for this fast; instead, it is simply said, “The distress that occurred on this day is not known.” But later, rabbis interpreted that the day of Jesus’ birth was the cause of this fast. However, there is no Jewish tradition associated with abstaining from food for a Christian feast.

Theories for the Origin of This Name

Several folk theories have been proposed to explain the origin of the word:

- Theory 1: The phrase “the night of the removal of that man from the world” is the inspiration for the name. Jews have always avoided discussing Jesus or even using his name.

- Theory 2: A coded term used to keep the beginnings of the Jewish words (“Nisht Yiden Tarn La’er’an”) which means “Jews are forbidden to study Torah”.

- Theory 3: Perhaps because no one was studying the Torah at that time, “Nittel Nacht” was a common name for the night in Eastern Europe.

- Theory 4: “Nolad Yeshu Tet L’Tevet” is an initialism for the Hebrew phrase “Some believe that the 9th of Tevet fell on the same day as Jesus’ birthday.”

Another theory contends that the original name for Passover, a significant Jewish holiday, was “Chag HaNitu’ach” (the “Hanging Holiday”), a derogatory term Jews used to refer to Jesus because of the account of his execution by crucifixion on the eve of Passover (according to the Book of Acts) “for sorcery and inciting Israel” French rabbi Rashi used the word “Nitu’ach” (hanging) in his works as early as the 13th century. Over time, the written form of “Chag HaNitu’ach” morphed into “Chag HaNitul” and then “Chag HaNittel” to conceal its true meaning from non-Jews.

It is not surprising that some Jewish communities still practice this ritual today despite its roots in historical and theological contexts given the complex interaction between cultural practices and religious beliefs.