Elected King of Poland, Stanislas I Leszczyński was forced to give up his throne in 1709 but regained it after the death of Augustus II (1733). While he was supported by France, Spain, Sardinia, and Bavaria, his rival Augustus III (the deceased king’s son) received backing from Russia, Austria, and Saxony. This rivalry led to the War of the Polish Succession (1733-1735), at the end of which Stanislas renounced the Polish throne.

As compensation, he was granted the duchies of Lorraine and Bar. Constantly forced to flee, he was a philosopher, always in good spirits, and knew how to enjoy life, saying, “He who possesses much is not the happiest: it is he who desires little and knows how to enjoy what he has.” He was also the great-grandfather of three Kings of France: Louis XVI, Louis XVIII, and Charles X.

Summary of Key Achievements

- King of Poland (1704–1709 and 1733–1736), though both reigns were marked by political conflict and eventual exile.

- Duke of Lorraine (1737–1766), where he ruled with great success, promoting education, culture, and social welfare.

- Cultural contributions, including the construction of the Place Stanislas in Nancy, which remains a symbol of his legacy.

- His daughter, Marie Leszczynska, became the Queen of France through her marriage to Louis XV, linking Stanislas to one of Europe’s most powerful royal families.

Early Steps in Politics

Stanislas Leszczyński was born on October 20, 1677, into an influential family belonging to the Polish nobility since the 16th century. His father was the Palatine of Poznań and the Grand Treasurer of the Crown, while his mother was the daughter of a renowned general who had defeated the Swedes and Cossacks. He studied in Leszno, Greater Poland, learning sciences, mathematics, and literature, and he spoke Latin, German, Italian, and French fluently. At 18, his educational journey took him to Vienna, Venice, Rome, Florence, and Paris, but he had to cut it short in 1696 due to the death of King John Sobieski.

Holding the title of Count of Leszno and acting as the governor of Poznań, he made his first political moves and sat in the senate. Stanislas was elected to the diet preparing for the final election of a new king. Facing two tough competitors (the Prince of Conti and the previous king’s son), he withdrew from the final vote and left the throne to the King of Saxony, Frederick Augustus, who was crowned in Krakow in September 1697 as Augustus II. Stanislas had the honor of offering the assembly’s condolences to the widow of King John Sobieski, impressing everyone with his oratory skills.

At 21, in May 1698, Stanislas married the daughter of a Polish magnate, Catherine Opalińska, who gave him two daughters: Anna in May 1699, and Maria in June 1703. Her dowry included sixty towns and one hundred fifty villages, giving him control of a vast estate when his father, Raphael III, died in 1703.

Stanislas Leszczyński: The Short-Lived King of Poland

Charles XII of Sweden refused to accept the alliance that Augustus II had signed with Russia and Denmark against him. Impressed by Stanislas’s good nature, Charles maneuvered to demonstrate Augustus II’s incapacity to rule and install Stanislas on the throne. This was accomplished on October 4, 1705, in Warsaw, but not without difficulty, as Augustus II attempted to kidnap Stanislas! The new King of Poland could rely on his “protector” until 1709, when Charles XII suffered a major defeat in Russia and fled to the Turks. With Russian and Saxon armies advancing on Warsaw, Stanislas had no choice but to abdicate.

While informing Charles XII, Stanislas took refuge in Stettin and later Stockholm. Unlike the optimistic and victorious Swedish king, Stanislas knew that Poland would suffer more if he persisted. He had lost all his possessions and was now living as a refugee abroad. Meanwhile, Augustus II reclaimed Poland. Despite Charles XII’s insistence to hold on at any cost, Stanislas decided to join him in Turkey during the winter of 1712, disguised as a French officer.

After a complicated journey, including an arrest upon arrival and a quick release, Stanislas convinced the Swedish king to accept his abdication. In a moment of understanding, Charles XII offered him the Duchy of Zweibrücken in Germany as he waited to reclaim his Polish kingdom.

Stanislas traveled back through Vienna and Lorraine. In Lunéville, in need, he pawned his jewels. Despite using the alias “Count of Cronstein,” he was recognized by Mr. de Beauvau, loyal to the Duke of Lorraine, who allowed him to keep his jewels and lent him the estimated amount.

By early July 1714, Stanislas arrived in Zweibrücken and found an old castle. The income was 70,000 écus, but 400 Swedish troops in the garrison consumed much of it. Always good-natured, Stanislas adapted to this situation, and three months later, he brought over his wife and two daughters. He embraced this new peaceful life, despite the premature death of his eldest daughter in June 1717.

In Poland, Charles XII continued to push for Stanislas to reclaim the throne, although Augustus II attempted to capture him again in August 1717. After Charles XII’s death in late 1718, Stanislas was forced to relocate, first near Landau, then to Wissembourg in 1719, thanks to Regent Philippe d’Orléans, who granted him a pension of 4,000 livres a month. The Duke of Lorraine lent him an additional 30,000 livres

Lacking the funds to settle, Stanislas pawned his jewels again and proposed to Augustus II: he was ready to give up his crown if he could recover his property. He needed to marry off his second daughter, who had just turned 18. Suitors were scarce due to the family’s poverty, but Stanislas made peace with the situation, enjoying a happy affair with a French officer’s wife, philosophizing, hunting, and savoring the simple pleasures of life.

Father-in-Law to Louis XV

In France, after the departure of the Spanish Infanta, who was too young, seventeen candidates remained for Louis XV’s marriage, from an initial ninety-seven. Either they were not Catholic or, like Stanislas’s daughter, were too poor. The Duke of Bourbon, serving as regent after the death of Philippe d’Orléans, offered to marry Marie, and Stanislas was pleased with the outcome. In February 1725, a portrait painter for the royal court arrived and left with Marie’s portrait.

In early April, the Duke of Bourbon asked for her hand… on behalf of the King of France!

As Stanislas fainted, France was taken aback, but Louis XV was pleased with the portrait: “neither beautiful nor pretty, but with a fresh complexion, lively eyes, cultured, gentle in character, and kind-hearted like her father.” When Stanislas recovered, he reclaimed his pawned jewels with the help of a 13,000 livres loan from the Strasbourg government.

The marriage took place by proxy on August 15. Stanislas received good news in early September, thinking, “I lost the Polish throne, but my future grandson will ascend the throne of France,” and radiated with happiness. In 1729, Louis XV settled his in-laws at Chambord with a modest pension, but the castle was empty. Accustomed to having little, Stanislas managed his funds wisely, leaving much of the castle unfurnished. Life unfolded quietly between his devout wife, his mother indulging herself, his forest walks, and his readings. “We live in great tranquility, which makes my life sweet,” he said, having long given up on the Polish throne, as no one in France would act while Augustus II was still alive.

Stanislas Leszczynski Regains His Throne of Poland…

August II died in February 1733, and several candidates for the Polish throne emerged, including his son August III and Stanislas Poniatowski, a former loyal supporter of Stanislas Leszczynski. The Marquis de Monti, French ambassador to Poland, made every effort to help Stanislas reclaim his throne despite his exile. With the support of sympathizers, Monti spared no expense, explaining that Stanislas had the backing of the King of France, who would never invade Poland even though neighboring countries (Austria, Prussia, Russia) were threatening. He even assured that France was ready to defend Poland in case of an invasion by any member of the Treaty of the Three Black Eagles (Germany, Russia, and Prussia, who sought to prevent any Polish claimant from ascending the throne).

By March 1733, Monti requested that France send Stanislas to Poland, but he hesitated. While confident about reclaiming his throne, Stanislas was unsure of the reception he would receive from the Polish people. Brave and clear-sighted, he realized he didn’t have the support of the French Prime Minister; if war broke out, he couldn’t count on France’s aid. In August 1733, Stanislas set sail from Brest but was stopped in Copenhagen by the Tsarina, who blocked the roads.

Eventually, he disguised himself as a German merchant’s clerk and traveled by postal carriage. He arrived on September 8, just days before the election on September 11, which Monti had masterfully organized. On September 10, Stanislas was recognized leaving the embassy, and the public was ecstatic—no one had expected his presence! The next day, he was unanimously elected, with only three abstentions. Meanwhile, 5,000 Polish soldiers deserted!

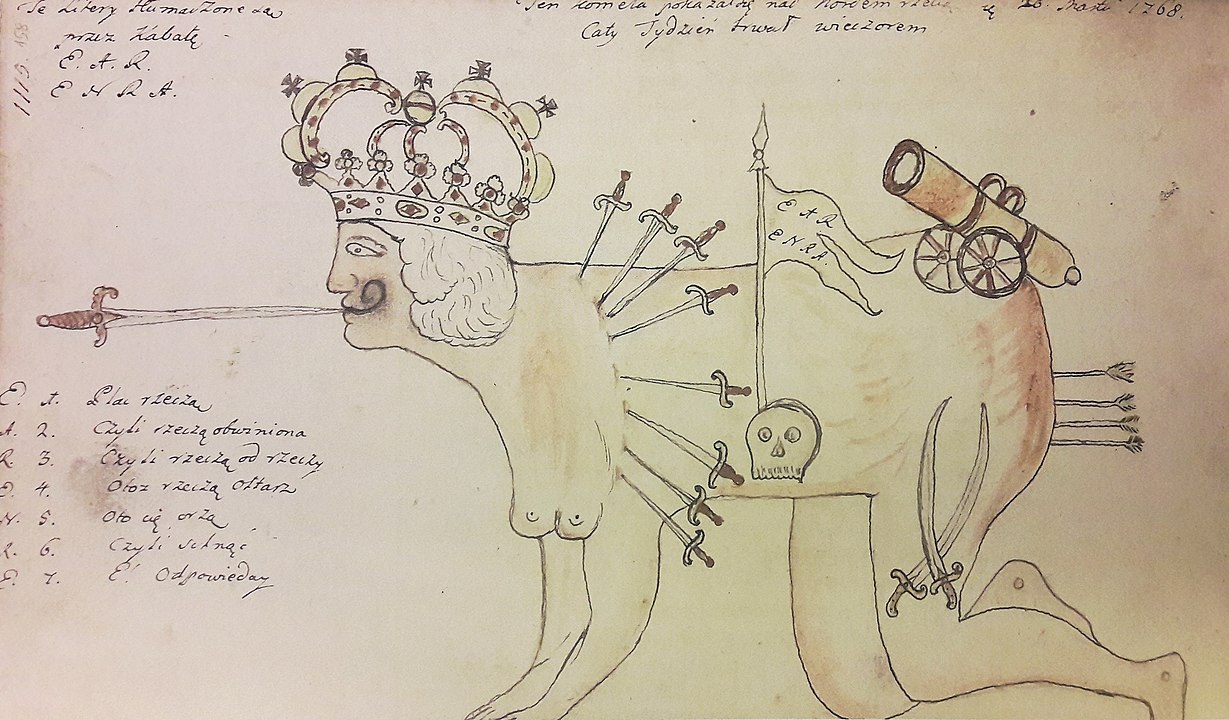

A Master of Escapes

Barely elected and knowing the Russian army was advancing, Stanislas engaged in two glorious battles. But faced with the overwhelming number of attackers and lacking a regular army, he left Warsaw on September 22, heading to Danzig, where he awaited help from France.

That help would never arrive. Louis XV had decided to declare war on Emperor Charles VI (an ally of the Russians invading Poland), stationing his troops on the German-Italian border. Thus began the “War of the Polish Succession.” On October 5, 1733, August III was crowned with the support of 40,000 Russians, 20,000 Saxons ravaging the country, and 36,000 soldiers advancing on Danzig!

Finally, reinforcements arrived in April 1734—but with only 1,950 men, each with 20 bullets!

They quickly retreated, showing “good sense” in the face of the overwhelming enemy forces. As the Russians issued an ultimatum—”For the freedom of Danzig, hand over the King of Poland or let him flee”—the city continued to fight despite the soldiers’ exhaustion. In late June, the ambassador organized an evacuation plan: slipping past enemy posts, crossing the Vistula River, and reaching Prussia.

Furious that Cardinal Fleury had refused to send more help, Stanislas fled once again, maintaining his good humor. Assisted by a Swedish general, both disguised as peasants, he undertook a perilous journey. Along the way, the Polish king, who was also the French king’s father-in-law, was reprimanded by his guides. This was no time for royal airs—it was no longer about keeping the throne but saving his life, as enemies were everywhere, and a hefty reward had been offered for his capture, “dead or alive.”

The escape took over a week, traversing canals and moving from farm to farm, hidden in carts covered with goods. Eventually, he reached safety and was welcomed by the King of Prussia in Königsberg in early July. Frederick William I offered him an honor guard and a respectable pension. A few days later, Danzig capitulated, and Stanislas’ small band of loyalists was imprisoned in a castle near Marienburg by the Russian army.

In Versailles, no one dared tell the Queen of France the full story, to the point where pamphlets were printed in support of Stanislas! Meanwhile, the King of France signed a famous treaty known as the Pragmatic Sanction: Francis III, Duke of Lorraine, married Maria Theresa of Habsburg, ending the War of Polish Succession. France acquired the duchies of Bar and Lorraine, intending to install Stanislas there!

Stanislas Leszczynski Rules Over the Duchies of Bar and Lorraine

After two years of negotiations, Stanislas Leszczynski signed his abdication to the Polish throne on January 27, 1736, pressured and forced by Versailles. Even his daughter urged him to accept, explaining that Lorraine was close by, and though it wasn’t Poland, it was still a duchy where he wouldn’t be a king without a throne. Forced to sign the “secret declaration of Meudon” in early June, which stated, “His Polish Majesty, not wishing to burden himself with the administration of the finances and revenues of the duchies of Bar and Lorraine, leaves that responsibility to the King of France, from now and forever,” Stanislas was granted an annual income of 2,000,000 livres, a chancellor to manage affairs, and the honorary title of King of Poland. Stanislas would reign without ruling! As was his nature, he accepted this with philosophical grace.

Antoine Chaumont de la Galaizière, urged by Cardinal Fleury, took control of the duchies in February and March 1737, wielding full power. Stanislas made his official entrance into Lunéville on April 3 before a reluctant populace but reunited with an old acquaintance, Mr. de Beauvau, who had crossed his path 23 years earlier and set him up in his private mansion. Stanislas was happy and busied himself with restoring Lunéville Castle, which was uninhabitable, and furnishing the Bar Castle. Who would have thought he would reign over his duchies for 29 years and be beloved?

Stanislas “the Benevolent”

From the moment he arrived, though unwelcome, Stanislas Leszczynski got to work, establishing his Council of State, Finance, and Commerce. He spent his money on charitable works, fought against famine, created a form of social security to cope with unforeseen events like accidents, illness, or disability, and set up free legal consultations for the poor. In 1748, he founded an order of the Brothers of Schools and contributed to school maintenance, ensuring free education for several schools in Nancy. This kind man “smoothed the rough edges” when his chancellor imposed French laws.

Everything went smoothly until 1740 when the War of Austrian Succession began. Three years later, despite French armies stationed in Strasbourg, Stanislas fled Lunéville as the Germans advanced, seeking refuge in Metz. In 1746, he returned to Lorraine and took care of his castle, which had burned down in 1744. Queen Catherine died in March 1747, and the Marquise de Boufflers, nicknamed “the Lady of Pleasure,” became his mistress. Stanislas enjoyed life and, thanks to his passion for desserts, invented the “baba”: finding the kouglof too dry, he soaked it in rum. He was reunited with old escape companions: Thyange, the Chevalier de Solignac, Tercier, and he welcomed Montesquieu in 1747 and Voltaire in 1748-1749. His court was “more breathable” than Versailles, a haven of peace with a love for intellectual pursuits!

Architect of Lunéville and Nancy

Major works were undertaken at the Château de Lunéville, where he even created a throne room. He redesigned the gardens, installed a Turkish-inspired kiosk, a pavilion in the Chinese style, and in 1742, added a series of 88 automatons at the “Rock.” He also had the “Chartreuses” built for his favorite courtiers so they could host salons. Visitors came from far away to admire these wonders of Lunéville. All of this was gradually destroyed by Louis XV after the death of Stanislas, as the king wanted to transform the château into a military barracks!

In Nancy, he built the Church of Notre Dame de Bonsecours in 1738, unified the medieval Old Town and the New Town, and used his own funds to develop the Royal Square (future Place Stanislas), which was inaugurated in 1755. He also created a large public library, a Royal Society of Sciences and Fine Letters in 1750, and the Royal College of Medicine in 1752.

A Fatal Day for Lorraine

On February 5, 1766, Stanislas Leszczynski got too close to the fireplace, and the fur robe (a gift from his daughter) he was wearing caught fire. He tried to extinguish the flames but fell into the blaze.

By the time the guard managed to enter the room, it was too late: one side of Stanislas’s body was burned, and one of his hands was charred.

Stanislas died seventeen days later, on February 23, 1766, at the age of 88. His remains rest in the crypt of the Church of Notre Dame de Bonsecours, alongside his wife, Catherine Opalinska.

Following the agreements made with Louis XV, Nancy became part of France, and in 1831, the population installed a statue in his honor at the center of the Royal Square, with the inscription: “To Stanislas the Benefactor, from grateful Lorraine.”