What has not changed since the time of ancient Rome? Given the profound impact of ancient Rome on human civilization, it is possible that at some point in medieval Europe people held a strong belief that “civilization is in decline,” vividly recognizing the many changes that had occurred in ancient Rome. Visiting any ancient Rome exhibitions prompts you to contemplate, “Wasn’t the foundational aspect of human existence, ensuring comfortable living conditions, already well-established during the ancient Roman era?” This question serves as a poignant reminder of the remarkable advancements achieved during that time.

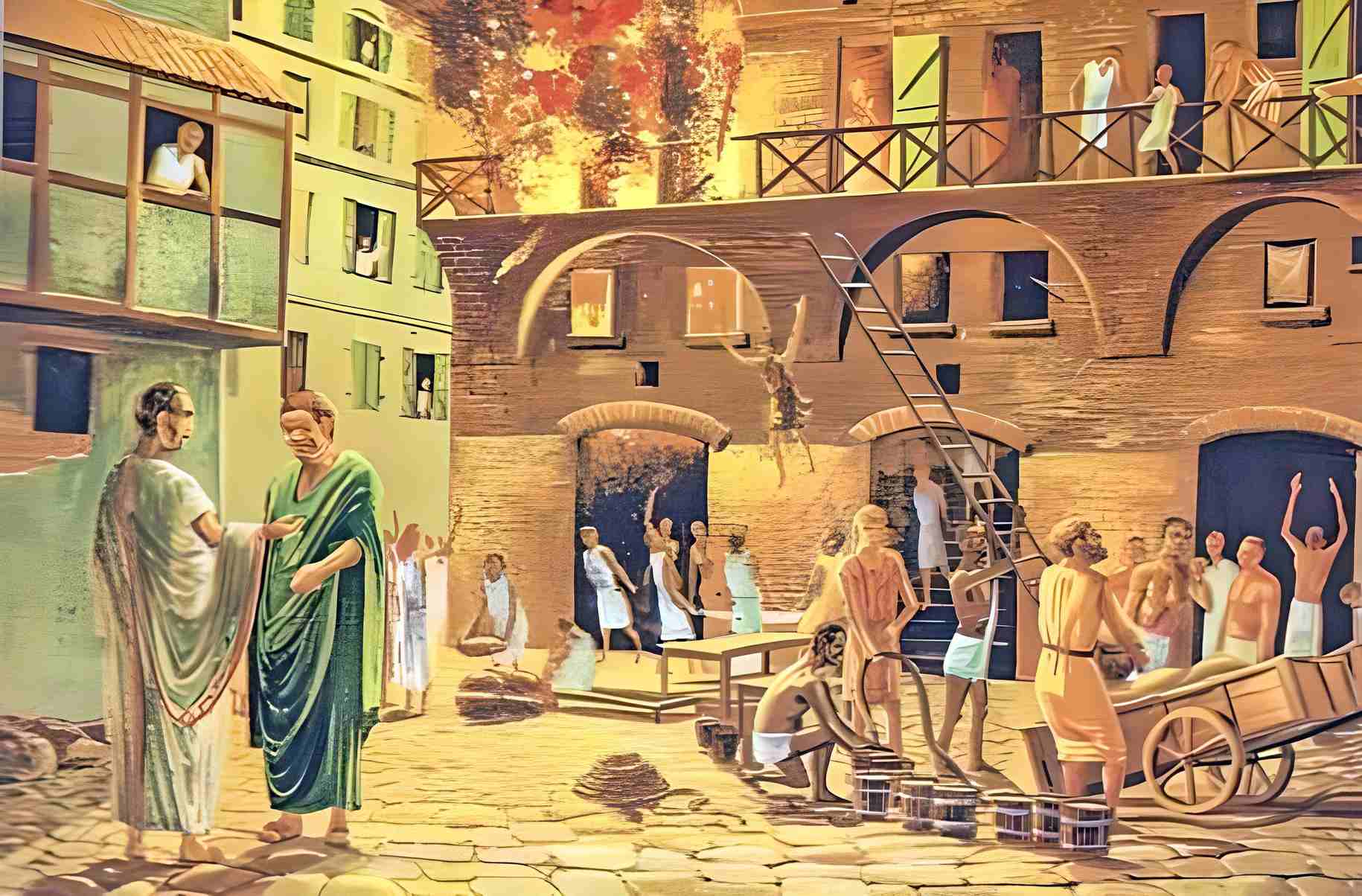

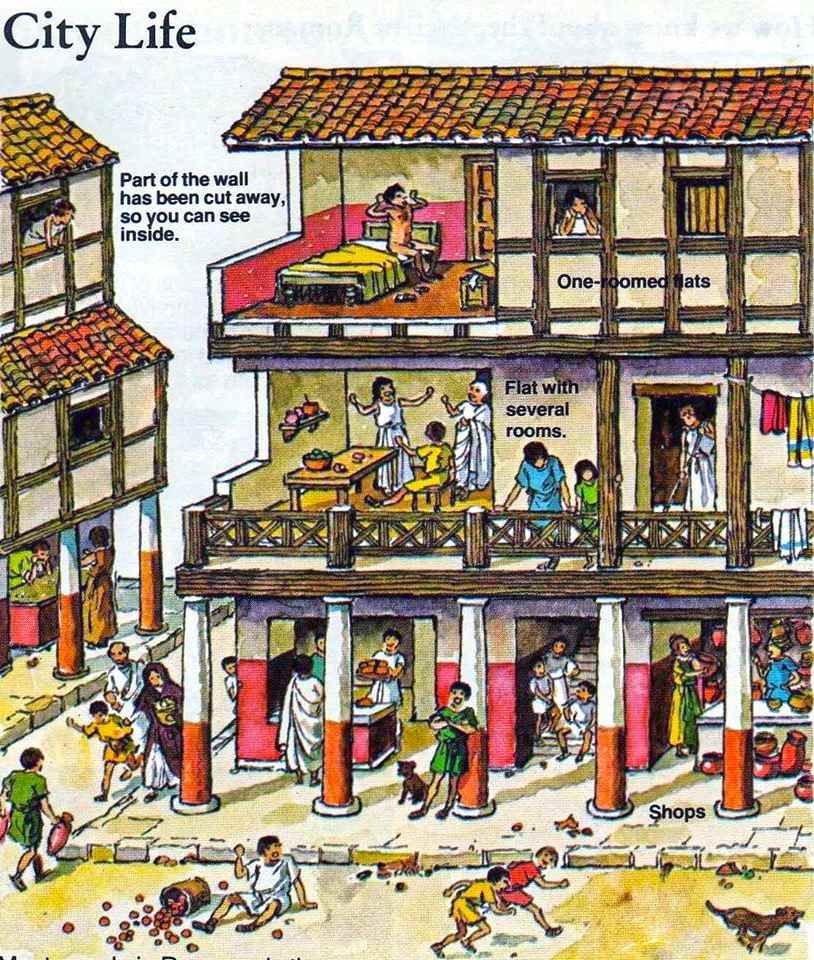

Rental Housing

The Romans were not the first to realize the financial benefits of renting out their homes to tenants in return for monthly payments. The practice dates back far further than that. So many people rented their houses in ancient Rome because Plebeians (lower- or middle-class citizens) made up about 95 percent of Rome’s population. Typically, a family would pay a year’s worth of rent in advance to live on the insula’s first level since it was the costliest. Similar to current apartment complexes, landlords would rent out ground-floor spaces to businesses.

Tenancy agreements: Several aspects of Roman rental housing from antiquity have survived to the present day. One such aspect was the availability of tenancy agreements, in which renters would make a monetary commitment to their landlords in exchange for the right to inhabit a property for a certain amount of time.

Maintaining properties: Another feature that has endured is the responsibility of landlords to maintain rental properties. In ancient Rome, landlords were expected to ensure that the rented dwellings were in habitable condition by performing necessary repairs and upkeep.

Dispute resolution mechanisms: Landlord-tenant disputes were prevalent in ancient Rome, mirroring the characteristics of today’s rentals. The rights of both tenants and landlords were protected by the law, just as they are today. Problems with rent payments, property maintenance, and the enforcement of contractual duties were resolved with the use of these procedures. Rental housing has always had a need for fair and reasonable remedies, and conflict resolution methods.

See also: What Was Daily Life Like in Ancient Rome?

Tableware

Plates and bowls: There were several characteristics of Roman tableware that have survived to the present day. The Romans used plates and bowls made of clay, bronze, or silver for their dinner tables. These containers were not only useful for serving food, but also added visual appeal to the dining experience. Ceramic and porcelain dishes and bowls are still widely used in modern households. The continued use of these basic pieces of tableware exemplifies the ongoing impact of ancient Roman tableware on contemporary eating customs.

Utensils: Another piece of Roman dinnerware that has survived the test of time is the utensil. We still follow the ancient Roman practice of using cutlery like spoons, forks, and knives when we dine. Utensils have served the same essential purpose throughout history, despite variations in form and substance.

Drinking vessels: There was a consistent theme running through the form and function of ancient Roman drinking containers. Wine, water, and other drinks were often consumed from cups and goblets crafted from pottery, glass, or precious metals. Glass, ceramic, and metal continue to be popular materials for drinking vessels in the modern period. These dishes’ longevity exemplifies how ancient Roman and contemporary cultures value similar qualities in their tableware: utility, beauty, and social importance.

Decorative elements: Ancient Roman tableware is also famous for the legacy of its ornamental aspects. Their dinnerware was embellished with intricate engravings, patterns, and motifs. Even in modern times, tableware with detailed designs, exquisite patterns, or unique touches is highly prized.

See also: Since When Do Westerners Use Cutlery?

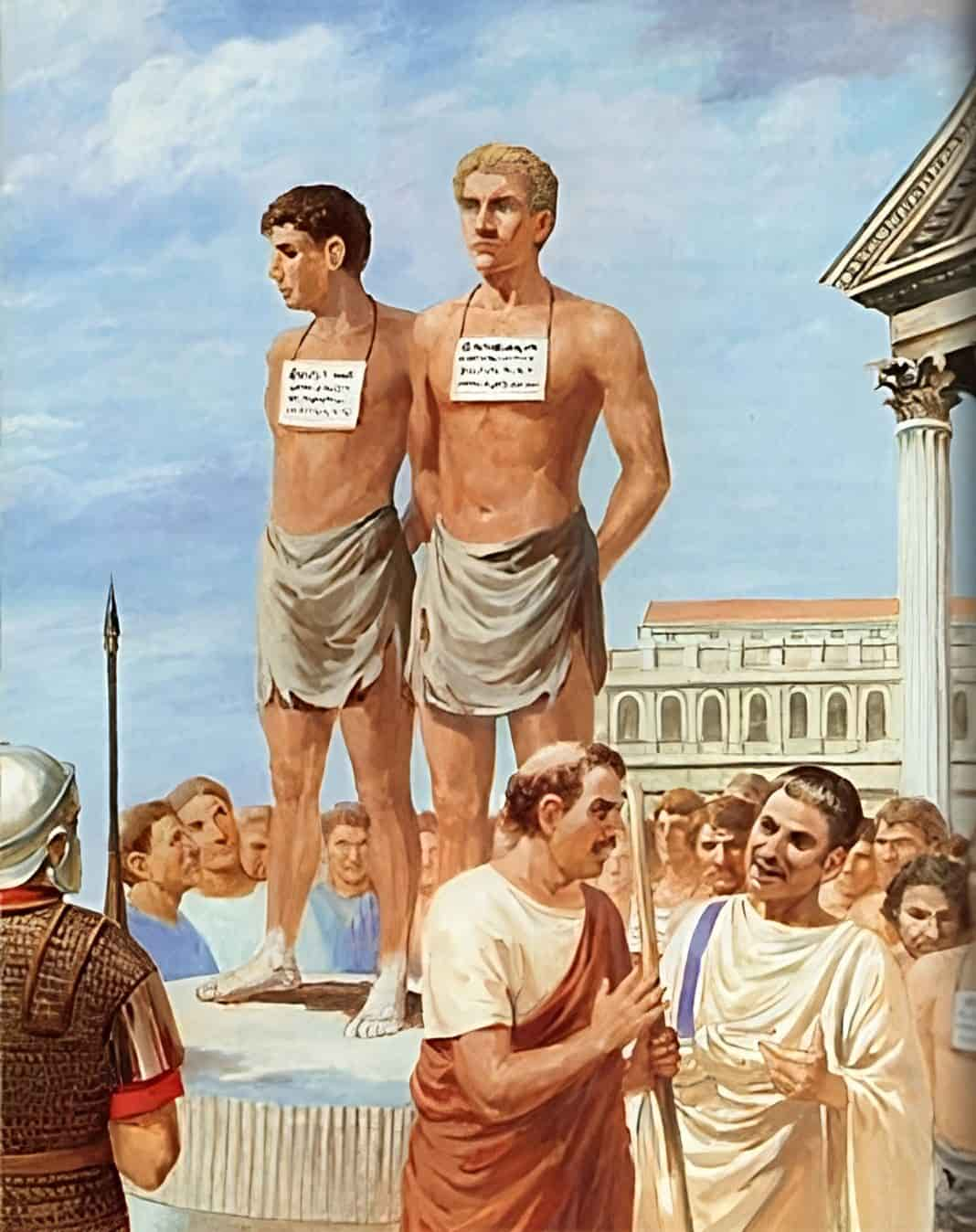

Coinage

Although coinage had been in use long before the time of the Roman Empire, the Romans did much to improve upon it and standardize it.

Standardized denominations: Ancient Roman coinage shares several similarities with modern-day currency systems. Just as today’s coins and banknotes have standardized denominations, Roman coins were issued at fixed values. The gold aureus, silver denarius, and bronze sestertius were among the commonly used denominations, ensuring consistency and facilitating transactions.

Portraits of national leaders: Secondly, similar to how modern currencies feature portraits of national leaders, Roman coins prominently displayed the likenesses of emperors and other influential individuals.

Inscriptions and symbols: Additionally, both ancient Roman coins and modern currencies bear inscriptions and symbols. Roman coins contained important information such as the issuing authority’s name, denomination, and minting year, while modern currencies feature similar inscriptions denoting their country of origin and value.

Luxury Homes

While some of the features of luxury houses may have changed since ancient Rome, the desire for a pleasant place to live has not. Luxury homes and villas were available even in ancient Rome, with amenities such as heated floors, mosaic-tiled ornate walls, decorative floors, and even indoor plumbing, all of which still exist in today’s houses.

Atrium: The hallmarks of a well-appointed Roman home have survived the centuries. Atriums are open areas in the middle of a home that often include a skylight or other opening to let in light and air. This architectural feature is still admired because of the positive impact it has on a home’s airiness and brightness.

Plumbing system: The sophisticated Roman plumbing systems delivered flowing water to residences, allowing for the installation of luxuries like baths and toilets in individual bathrooms. The Romans’ innovative plumbing and widespread access to clean water for personal cleanliness attest to their awareness of the value of such amenities. There’s little question that this aspect of ancient Roman dwellings affected the evolution of plumbing systems in houses throughout history.

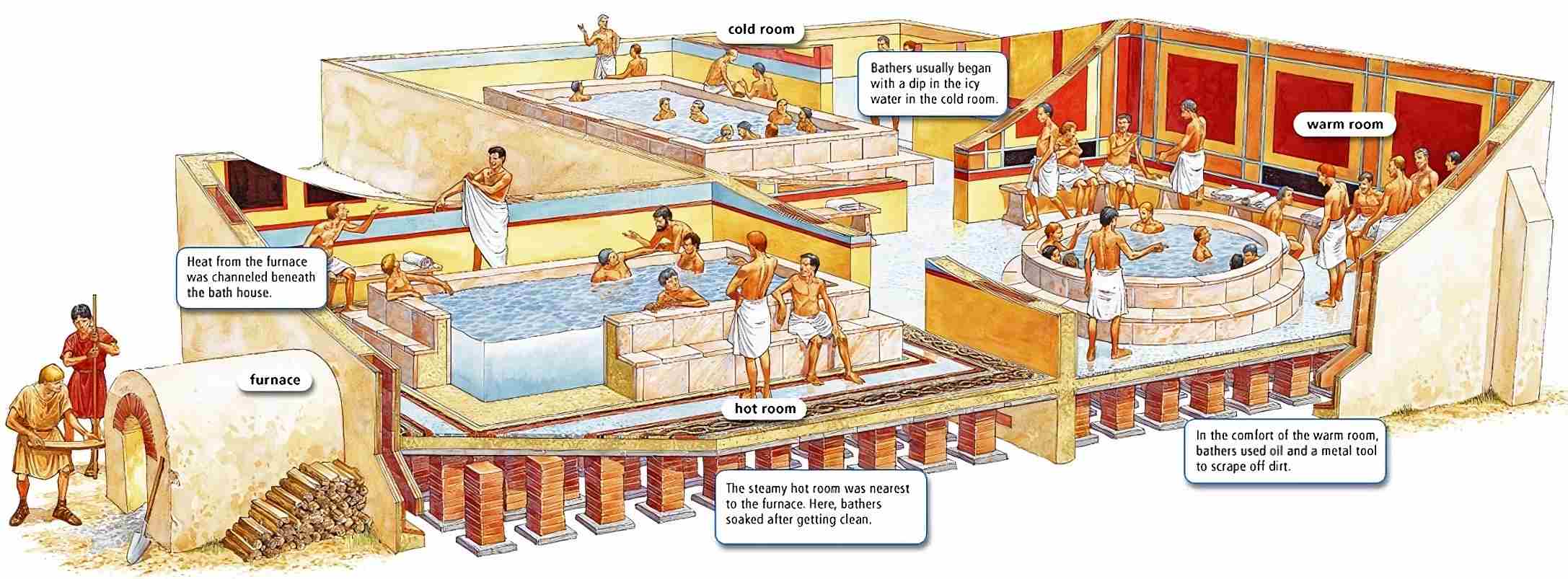

Hypocaust system: This novel underfloor heating system was another standout. Hot air or steam that was circulating under the flooring heated the chambers. Because of its usefulness throughout the year, not only during the winter, the hypocaust has been a popular addition to homes for ages. Multiple heated rooms, such as the caldarium, tepidarium, and frigidarium, provided a luxurious bathing experience.

Enclosed garden: The peristyle, an enclosed garden or courtyard framed by columns, enhanced the tranquility of the Roman outdoors. The idea of creating a personal sanctuary inside one’s own dwelling is still highly prized in contemporary design.

Private rooms: The design of a typical Roman home, known as a domus, contained distinguishing features that continue to influence modern architectural layouts. Private dining areas like the tricliniums offered elegant spaces for reclining and enjoying meals in ancient Rome. These areas, furnished with couches and low tables, facilitated the Roman tradition of dining while reclining, creating a relaxed and sociable atmosphere for residents and their guests. This design element still exists today.

An architectural principle that hasn’t changed much in modern home construction was how the Romans met their demand for solitude by clearly dividing their living space into public and private areas.

Aqueducts

The Romans built massive aqueducts to bring water from faraway areas to populated areas. While improvements in water transportation technology and materials have been made, the idea of using constructed buildings to provide potable water to urban centers has not changed.

They were and still are crucial for transporting water from where it is abundant to where it is limited, whether 2,000 years ago in ancient Rome, Italy, or today in California. Engineers have created brand-new aqueducts to transport water over long distances, frequently hundreds of miles.

Oldest running aqueduct: Some of Rome’s fountains even get their water supply from a Roman aqueduct that is still in use today. The Acqua Vergine, which was first constructed in 19 BC and has undergone several restorations, is still in use today. It is the oldest running aqueduct in the world today.

Oldest survived aqueduct: The Segovia Aqueduct (also known as El Puente for “The Bridge”) is an aqueduct that was constructed during the era of the Roman Emperor Trajan (98–117 AD) and is still in use today to transport water from the Frio River to the city of Segovia in Spain, a distance of 10 miles (16 km).

Although not exactly “today,” the Bogotá, Colombia, aqueduct, completed in 1955, stands out as one of the recently built, modern aqueducts.

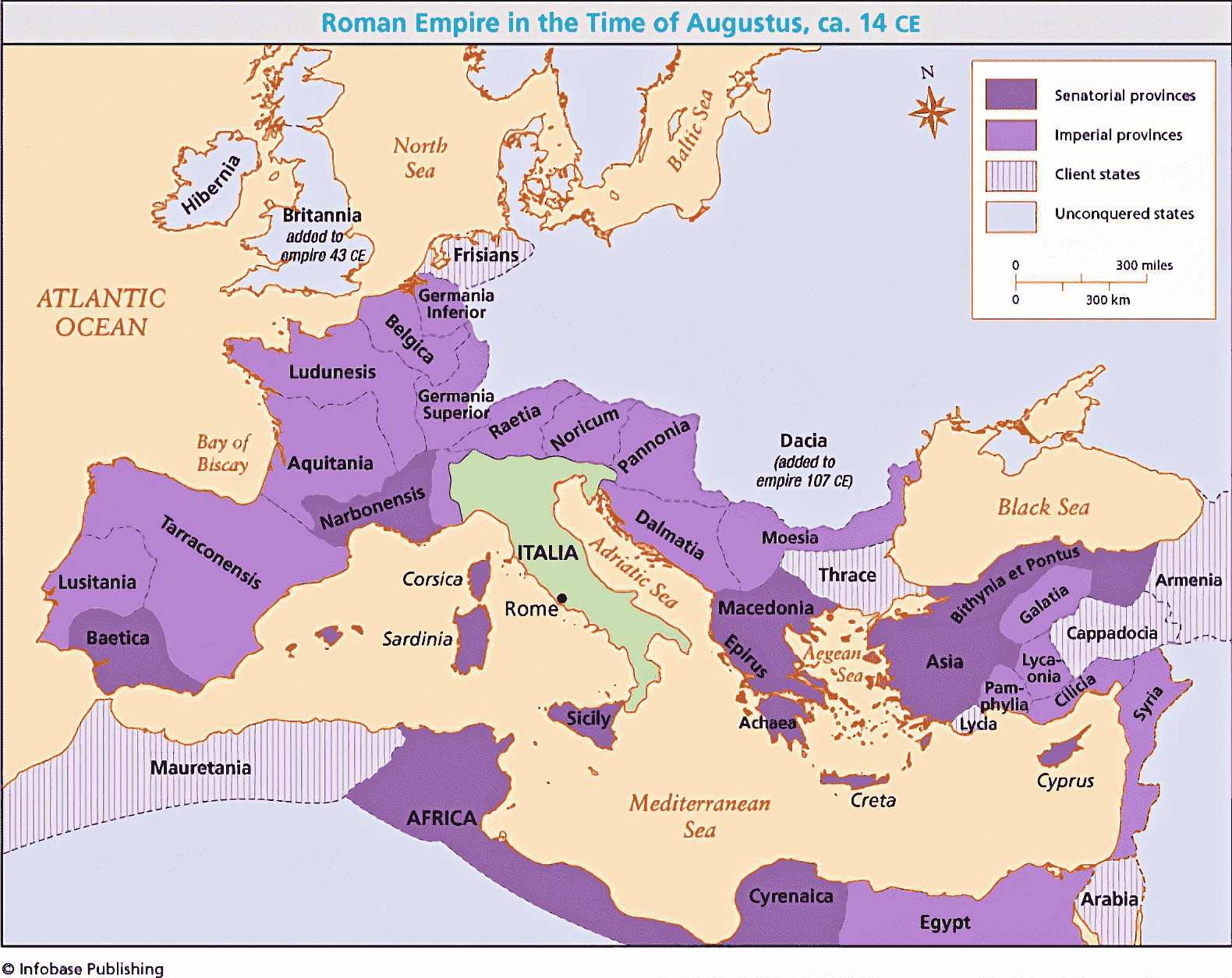

City Planning

Grid layout: Ancient Rome’s gridiron or cardo and decumanus street plans used a grid pattern to partition the city into square and rectangular sections. Many contemporary towns throughout the globe still have this grid layout.

Public spaces: The Romans placed a premium on the development of public spaces in urban areas. Civic, economic, and social life often converged in public gathering places like plazas and squares in ancient Rome. The public realm remains a focal point of urban planning in today’s cities.

Infrastructure: Ancient Rome’s infrastructure was state-of-the-art and much admired for its extensive network of well-constructed roadways, aqueducts for water supply, and sewage facilities. Although these aspects of infrastructure have been upgraded throughout history, they still serve as the basis for contemporary urban planning.

Zoning: The Romans were early adopters of zoning laws, which were designed to separate residential and commercial areas of a city. Partitioning land for different uses (such as residential, commercial, and industrial) is a tenet of today’s city planning.

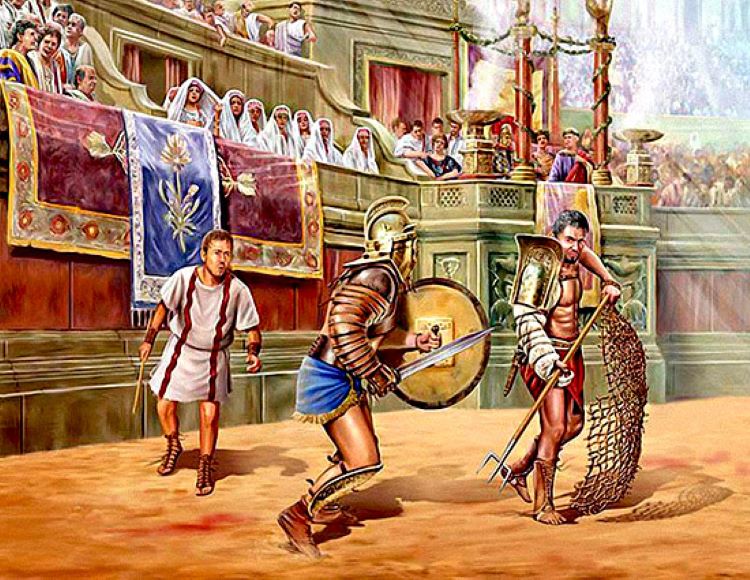

Monumental architecture: The ancient Romans built several very impressive buildings, including amphitheaters, temples, and public baths. Iconic structures and landmarks still stand as representations of cultural value in today’s cities.

Focus on public health: Public health was a primary concern for the ancient Romans when designing cities. Public amenities such as latrines and water fountains were installed to encourage good personal hygiene.

Transportation: Rome built an enormous network of roads, bridges, and docks, which aided commerce and communication. Cities today still spend money on transportation infrastructure like this.

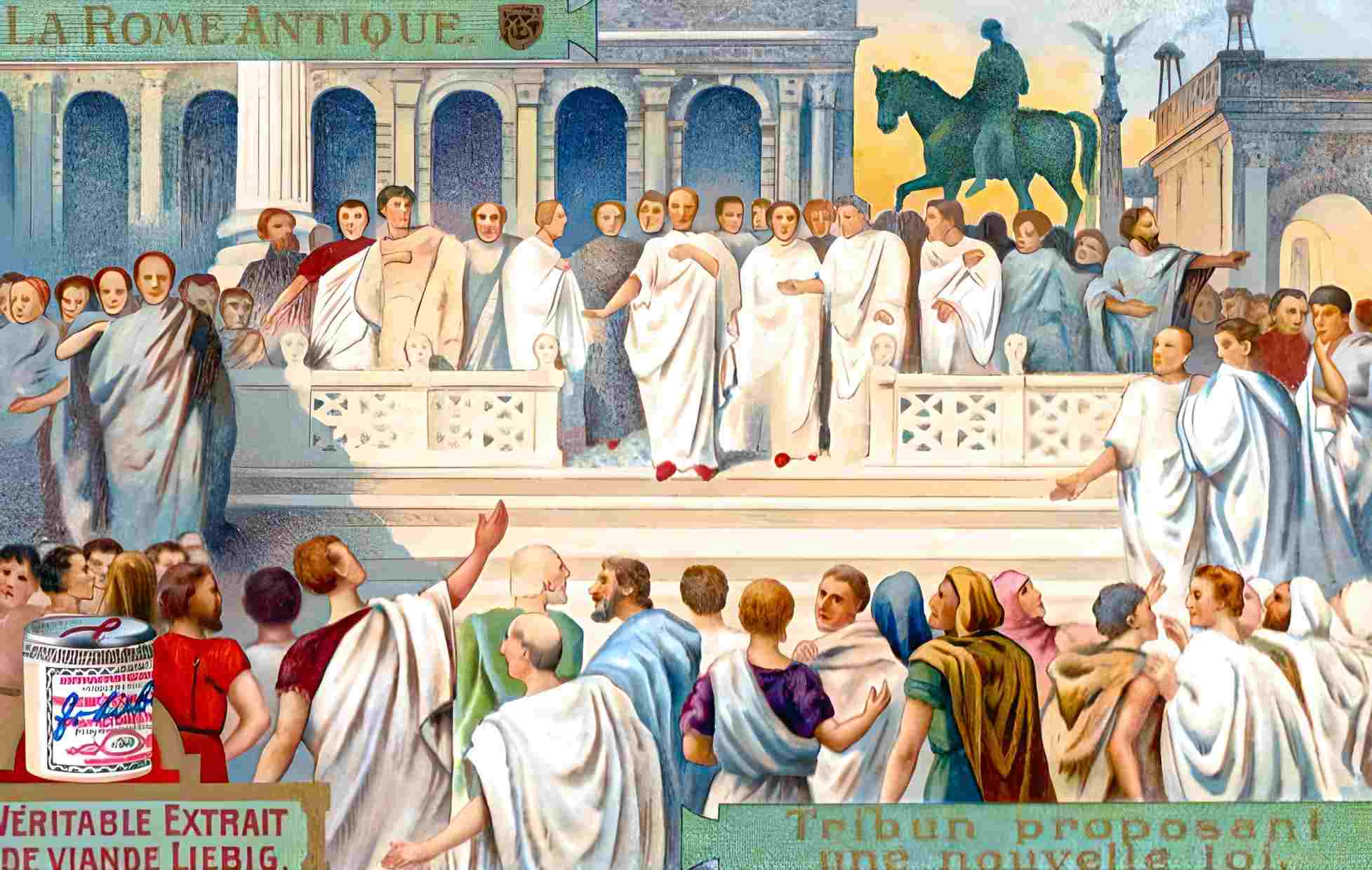

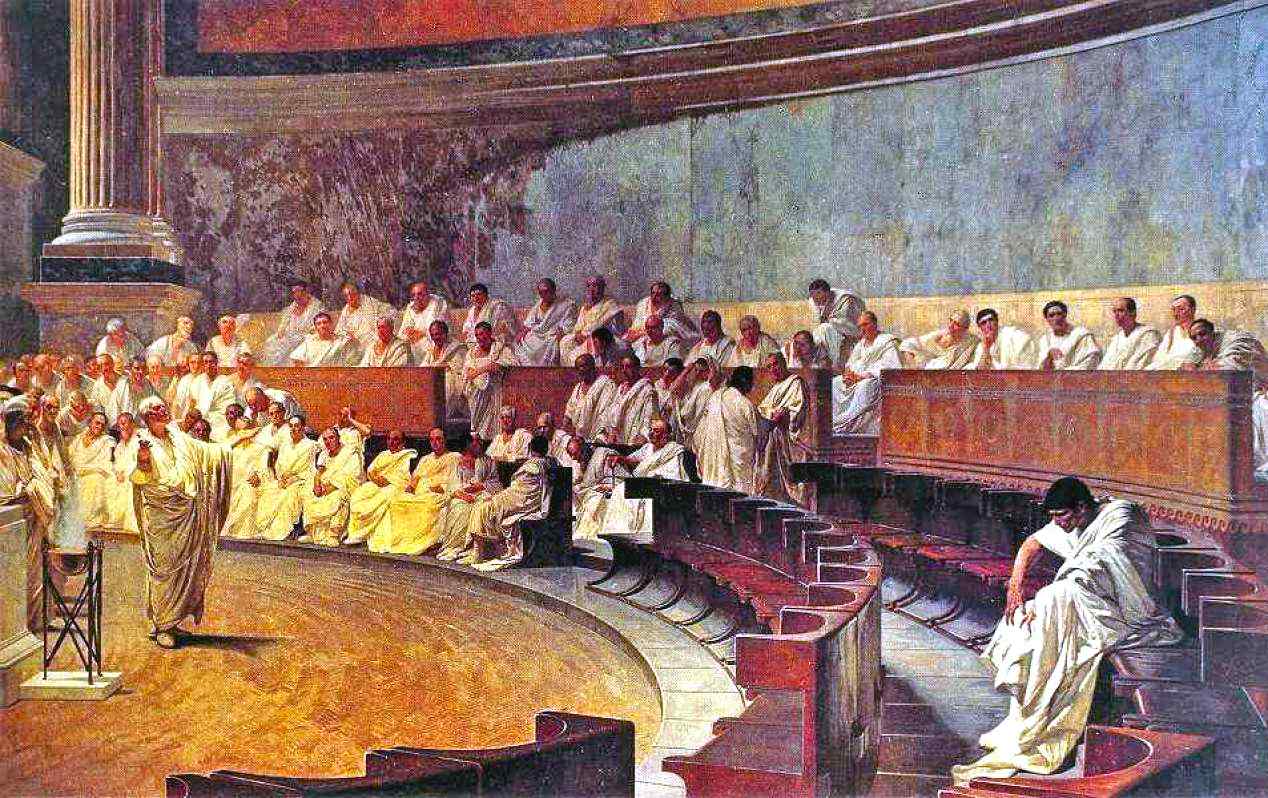

Legal Systems

Codification: The Twelve Tables (450 BC) were only one example of the complex legal rules enacted by Ancient Rome. Many modern legal systems still heavily rely on this principle of codification.

Precedent: The Roman legal system adopted the notion of precedent, wherein prior rulings provided a binding precedent for new cases. This tenet remains important to the common law system in use by many nations today.

Legal professions: Advocates (the ancient Roman equivalent of lawyers) and judges also played an important role in ancient Roman society. The importance of attorneys and judges as experts in the law remains unchanged in today’s legal systems.

Legal rights: The property rights, contract protections, and the guarantee of a fair trial are only a few examples of the individual liberties acknowledged by ancient Roman law. Legal safeguards in contemporary countries are still conceptualized in terms of these ideas.

Legal procedures: The examination of witnesses and the presentation of evidence were two examples of the legal processes and norms that were strictly adhered to in ancient Roman judicial proceedings. Modern legal systems share a commitment to procedural fairness and due process with their historical precedents.

References

- SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome by Mary Beard, 2015, Goodreads

- Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire by Jérôme Carcopino, 2013 – Amazon Books

- History Of The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire, by Edward Gibbon, 1776-88, The Project Gutenberg eBook