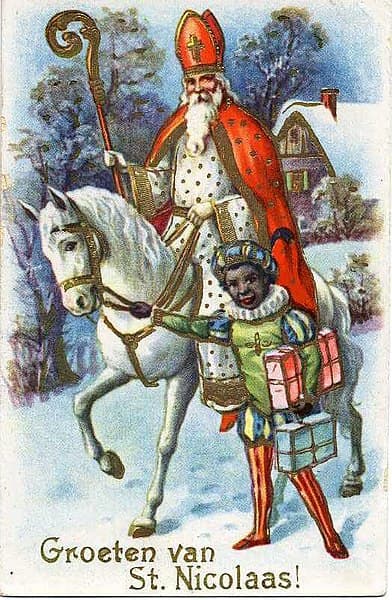

The Zwarte Piet (Dutch; West Frisian Swarte Pyt, “Black Peter”) or Piet is, in the Netherlands and Flanders, the helper of Sinterklaas, Saint Nicholas in the Dutch tradition. The Zwarte Piet, present everywhere in November and December, is extremely popular among the population, and the Sinterklaas festival is more significant than Christmas. In France and the French-speaking part of Belgium, the character is known as Père Fouettard.

Originally, Zwarte Piet was a frightening figure in Dutch folklore unrelated to the Sinterklaas tradition. It only became associated with St. Nicholas in the mid-to-late 19th century. From that time, it served a similar function to figures like Knecht Ruprecht, Schmutzli, or Krampus—punishing naughty children instead of the physically reserved Saint. In the 20th century, the single helper evolved into a group of Zwarte Piets assisting Sinterklaas. The performers’ faces are painted brown or black, and they wear colorful festive clothing reminiscent of 16th-century servants.

Since 2013, criticism has increased regarding whether the character of Zwarte Piet (as in the case of Blackface) could be racially charged. This was sparked by the Jamaican Professor of Social History, Verene Shepherd, who, as a member of a working group at the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR), called for the abolition of the Sinterklaas festival along with Zwarte Piet. The population responded emotionally to these allegations. Consequently, alternative costumes have emerged, where the black on the face is only suggested as soot, or performers are painted in colors like green or red. The character is increasingly referred to simply as Piet, rather than Zwarte Piet.

Zwarte Piet’s Function and Characteristics

The Sinterklaas festival on December 5th is the most popular folk tradition in the Netherlands, as a 2010 survey revealed. In its current form, it is unique to the Netherlands and Flanders. It is primarily a children’s festival, with adult participation as well. According to tradition, Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet bring gifts during the Sinterklaas festival on December 5th. Zwarte Piet climbs through the chimneys of houses—where people sleep—and distributes sweets. Additionally, he serves as Sinterklaas’s assistant, holding his book or staff, guiding his horse, or performing other tasks for him.

Until the 1970s, Zwarte Piet often carried a rod, with which he punished naughty children. Nowadays, the rod is rarely seen in Zwarte Piet’s hand. Although it still exists as an attribute, it is no longer used. Some children are afraid of Zwarte Piet because all misdeeds are recorded in Sinterklaas’s book. Moreover, some parents tell their children that Zwarte Piet takes the stubborn kids to Spain in a jute sack.

In recent times, Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet can be seen in city centers weeks before December 5th, often near department stores. In mid-November, Sinterklaas makes a festive entry into a specific city, which is broadcast on television. Especially the Sinterklaas featured in the children’s television program Sinterklaasjournaal has many Zwarte Piet as helpers. Piet has been assigned various tasks, such as shopping, wrapping, transportation, etc. There is also now a leader of the Piet, known as the “Head Piet.” The fictional news program reports on the difficulties Piet faces on their way to the Netherlands. For example, one Piet lost the gifts, requiring a joint effort from the bishop’s entourage to save the celebration for the children.

In older depictions, Zwarte Piet had a black face, large red lips, an afro hairstyle, and golden earrings. He was wild, childish, and unreliable, playing pranks and speaking clumsily. According to a children’s song, he says: Want ook al ben ik zwart als roet / Ik meen het wel goed (Even though I’m black as soot, I mean well). Consequently, he had to assert his goodness because his appearance didn’t suggest it. Later on, Zwarte Piet became more serious and wiser, serving as support for the elderly Sinterklaas.

Zwarte Piet’s Origin

The cult around Saint Nicholas of Myra is ancient, while the Dutch Zwarte Piet can be traced back to the Baroque period and is mentioned as a frightening figure alongside entities like Poltergeist, Nightmare, and Klabautermann in Pieter Nieuwland’s 1766 work De bespookte Waereld ontspookt (“The haunted world dehaunted”). In the Alpine region, Krampus is documented as the black, demonic servant of Nicholas. This black-white contrast (Nicholas’s beard being white) has a pre-Christian origin, symbolizing the (rewarding) good spirit overcoming the (punishing) evil spirit. There is no evidence supporting a connection between Krampus and Zwarte Piet.

The “modern” Zwarte Piet originated with the teacher Jan Schenkman. According to Schenkman (1850), the Dutch saint resides in Spain. This might be due to the rhyme between the Dutch name for Spain, Spanje, and appeltjes van oranje (golden little apples, oranges), as found in the famous song about Piet Hein. Alternatively, it could be related to the fact that during the 16th century, when the children’s celebration was documented, the Netherlands, like Spain, belonged to the Habsburg monarchy. The presence of a Moor in Oriental attire on stage might be connected to the fact that Spain experienced nearly 800 years of Moorish rule in al-Andalus. The term “Moor,” often used for Zwarte Piet, can refer to both a sub-Saharan African and a darker North African.

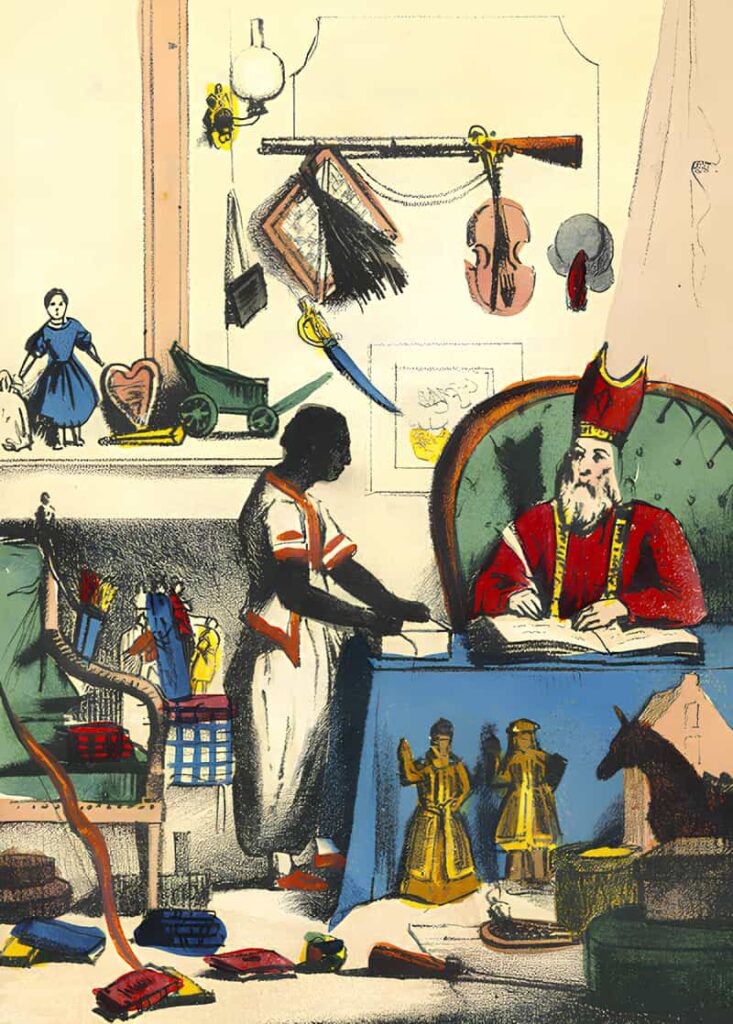

According to the director of the Rijksmuseum, there is a painting from 1520 depicting the court of Emperor Charles V. A proud black man is already shown with the attributes later associated with Zwarte Piet. However, Sinterklaas initially had no companion; it was only in 1850 that Schenkman portrayed him with an unnamed black servant in his picture book. In a later edition from 1858, this figure wears a page uniform with breeches and a beret. Although Schenkman did not invent the companion, as there are indications of earlier use, he canonized it, according to the Meertens Institute for Folklore.

While a connection to slavery, prevalent in the Dutch colonies at the time, cannot be proven, the stereotypical depictions may have been influenced by the contemporary discourse on colonialism and slavery. The name Pieter has been in use since 1859, and only around 1900 did the name Zwarte Piet become established. On the other hand, a connection to the black ravens of Wotan is more likely to be excluded, just as the comparison between the airborne Wotan and the rooftop-riding Sinterklaas is rather superficial. Additionally, Zwarte Piet is not black due to soot, as he is already black upon arrival by boat from Spain and not only after delivering gifts through chimneys.

Controversy

Isolated Zwarte Piet Protests

Since the 1970s, there have been occasional complaints about Zwarte Piet, as his appearance and behavior are seen by some as reminiscent of an uneducated Black person, raising concerns about racism. For instance, in 1987, a Black Dutchwoman expressed on the children’s program Sesamstraat that she disliked the tradition because, during Sinterklaas time, Blacks were referred to as Zwarte Piet.

In 2011, two Black Dutch individuals intended to hold a banner saying “Nederland kan beter” (“The Netherlands can do better”) during Sinterklaas’ entry. When the police prohibited this, they complied but revealed T-shirts with the inscription “Zwarte Piet is racisme” (“Black Pete is racism”). The police sought to prohibit this as an unauthorized demonstration, and when the two individuals did not comply, a scuffle ensued, leading to their arrest. They were fined 140 euros.

In 2013, the public broadcaster EenVandaag collected statements from dark-skinned Dutch people, often of Surinamese or Caribbean descent. Many recounted positive childhood experiences during Sinterklaas but also recalled instances of discrimination and bullying. Both adults and children made “jokes” about whether the dark-skinned child had arrived in the country too early or had missed the boat (back to Spain). If they spoke up against it, they encountered incomprehension, so they learned to adapt. As adults, many continued to celebrate Sinterklaas, but some avoided the festivities as much as possible. The festival, they argued, shouldn’t be abolished, but the companion should be adapted to modern times.

Accusations in 2013

In October 2013, a nationwide protest erupted in the Netherlands when a Jamaican professor of social history suggested that the country should abolish Zwarte Piet. Verene Shepherd has been part of a four-member Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent at the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCHR) since 2008, aiming to highlight human rights issues. In January 2013, the group asked the Dutch government for clarification on the Sinterklaas festival. The Zwarte Piet perpetuates a stereotype that portrays people of African origin as second-class citizens and incites racism, the group argued. They also mentioned hearing that Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet were proposed to UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage of the Netherlands. However, a government representative stated in July that the latter was not true.

Shepherd stated in an interview with a Dutch newspaper:

“As a Black person, I feel that if I were to live in the Netherlands, I would resist it. As a member of the research group, I am obligated to conduct more research, but as a Black person, I would certainly resist. […] We are investigating whether the information we have received is correct. If not, we will change our stance. But the complaints we receive point to racism and a return to slavery. That is what we are investigating.”

In her opinion, the Sinterklaas festival should take place for the last time in 2013, as having a single Santa Claus would be sufficient (instead of both St. Nicholas on December 6th and Santa Claus on the 24th). She wanted the issue to be addressed in the UN General Assembly.

The Belgian UNESCO representative, Marc Jacobs, responded a few days after the media uproar, stating that the working group could not speak on behalf of the United Nations or UNESCO. He called the working group incompetent and said their quasi-official request should not be taken seriously. The instrument of intangible cultural heritage was being misused. A delegation from the Dutch Parliament’s Second Chamber, located in New York, wanted to meet with the social historian and explain the Sinterklaas festival to her.

A Dutch online newspaper drew a connection between the debate and the question of compensation for the descendants of slaves. Caribbean countries have been demanding some form of compensation from the countries that have benefited the most from the slave trade for decades. In the summer of 2013, the leaders of 14 Caribbean countries in Miami formulated a corresponding demand for the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands. Jamaican academic Verene Shepherd was one of the driving forces behind the “battle plan” of these 14 countries.

Consent or Mediating Positions

Some voices questioned how Zwarte Piet was portrayed on this occasion. Peter Jan Magry, a professor of ethnology in Amsterdam, told Algemeen Dagblad on October 24, 2013:

“Because the Sinterklaas festival is almost in the genes of the Dutch, we have had blinders on regarding the appearance of Zwarte Piet. Pieterbaas has indeed transformed from a foolish bogeyman into a clever friend of children in recent decades, but he still has kinky hair, baggy pants, red lips, and large earrings. For outsiders, he is a black stereotype that is perceived as racist.”

Cultural traditions need to be thoroughly understood instead of immediately expressing an opinion. However, the appearance of Zwarte Piet has indeed changed insufficiently with society. From a servant, he has become a friend of Sinterklaas, no longer carries a rod, no longer speaks in crooked sentences, and is no longer a foolish grimace-maker. But it must change that he still looks like a Black person as imagined by a White person in 1858.

Some organizers and politicians have also moved in this direction or at least expressed understanding. If public opinion slowly changes, organizers and department stores would also adapt. The center-right Prime Minister Mark Rutte said he could hardly change Piet’s color, while Interior Minister Ronald Plasterk (Social Democrats) said that children would still have fun even if a few green or blue Piet joined the black ones in the future.

On the Caribbean island of Bonaire, which has had the status of a special Dutch municipality since 2010, Sinterklaas is also celebrated. Mostly dark-skinned residents paint themselves black or brown for their role as Zwarte Piet, while Sinterklaas paints himself white. Due to the influx, candidates have to audition, said the Sinterklaas coordinator of a youth center, and there have never been accusations of racism. In contrast, on the neighboring island of Curaçao in 2011, there was a discussion that led to painting the Zwarte Piet in different colors. Children were told that the boat had sailed through a rainbow. An employee of the youth center in Bonaire explained that Zwarte Piet got his color from the soot in the chimney. Residents of Bonaire prefer not to be reminded of the slave past and would rather see themselves as descendants of Indians.

Negative Reactions

In the broader population, a massive wave of protests has emerged with particularly intense emotions. According to a survey, 92 percent of respondents want to keep Zwarte Piet, and a Facebook support page called Pietitie (a portmanteau of Piet and petitie, Dutch for the petition) received 2 million likes within two days. It has been reported that tattoos related to the topic have suddenly increased.

Geert Wilders of the right-wing populist Party for Freedom suggested on Twitter that instead of celebrating Sinterklaas, the United Nations should be abolished. The UN complained that members of the volunteer human rights group were harassed, intimidated, and attacked for their personal integrity. The popular Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf referred to Shepherd, who was unreachable, as a “zeurpiet” (‘whining Pete’).

In Groningen, a foundation that organizes the festival for underprivileged children initially planned to accompany Sinterklaas with not only black but also yellow and green Petes. However, they reconsidered this decision after receiving death threats and accusations that the foundation was behaving like traitors during World War II or supporters of the National Socialist Movement. The editor-in-chief of two children’s magazines stated that the discussion was only taking place among adults, and their magazine for elementary school children would not cover it. Otherwise, it would have to be revealed immediately that they were just men in costumes. Children are conservative; they want everything to stay as they are accustomed to.

On October 26, 2013, according to police reports, 500 people peacefully demonstrated in support of Zwarte Piet on the Malieveld in The Hague. The event was initiated by a sixteen-year-old. During the demonstration, Facebook petitions were handed over to PVV parliamentarian Joram van Klaveren, who intended to take them to the Second Chamber. A black woman protested on the sidelines of the demonstration against the UN for its role in the transfer of the former Dutch colony Dutch New Guinea to Indonesia in 1969, justified by a controversial vote (Act of Free Choice). The woman was mistakenly taken for a Zwarte Piet opponent and was harassed and insulted by demonstrators (“Go back to your own country”). The police ensured the woman’s safety.

On October 24, literature scholar Marleen de Vries wrote in the newspaper de Volkskrant that the character of “Zwarte Piet” has always been adaptable. She traces the black man back to the Moors, who were present on the European continent early and for centuries due to the conquest of Spain (from 711 to; the abandonment of the last stronghold in 1492). Moors associated with a bishop have been known since the late Middle Ages. De Vries sees the prototype for “Zwarte Piet” in the Saracens, who were feared. She describes the portrayal of the Moor as part of European cultural history for 700 years. According to de Vries, referring to slavery is misleading.

UN and Dutch UNESCO List

Independent of Verene Shepherd’s group, the Sinterklaas festival was also examined concerning its inclusion on a UNESCO list for intangible cultural heritage. In early summer, the Sint Nicolaasgenootschap requested the festival’s inclusion in this list. The Knowledge Center Intangible Heritage Netherlands dealt with this matter.

The director of the center, during the consideration of the request, welcomed it but expressed concerns that the discussion about Zwarte Piet could resurface. She inquired about how the society intended to handle the issue. In turn, the Sint Nicolaasgenootschap refused to make any changes.

In 2015, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination issued a recommendation. The Dutch government should actively work towards eliminating negative stereotypes surrounding Zwarte Piet, especially those reminiscent of the slavery past. The Dutch delegation understood the pain and expressed openness to dialogue but rejected government intervention in defining or banning Piet’s appearance.

Highway Blockade 2017

On November 18, 2017, protesters traveled by bus to the province of Friesland. They intended to demonstrate against Zwarte Piet and racism during the Sinterklaasintocht in Dokkum. They had the municipality’s permission. On the A7 highway near Joure, they were stopped: activists advocating for Zwarte Piet blocked the highway with cars and threatened the demonstrators. Under police escort, the anti-Piet demonstrators returned while the mayor prohibited the anti-Piet protest, fearing chaos during Sinterklaas’s arrival.

As a consequence, 34 pro-Zwarte-Piet activists faced charges for the blockade. On November 9, 2018, the verdict was delivered. The judges largely followed the prosecution’s stance. The activists had prevented a demonstration, curtailing the demonstrators’ right to freedom of expression. Moreover, they significantly endangered traffic. Most pro-activists received 120 hours of community service. The ringleader, Jenny Douwes, received 240 hours of community service and a one-month suspended prison sentence. They are collecting funds through crowdfunding for an appeal.

Recent Developments

In November 2017, Algemeen Dagblad reported that TV presenter Humberto Tan had been under protection for a year and a half due to his remarks against Zwarte Piet. The reason was his solidarity with Sylvana Simons of the DENK Party, who also received death threats and required protection. In the same month, the newspaper declared a Sinterklaas ceasefire, a kind of truce in the interest of children. While Sinterklaas is in the Netherlands, discussions on the topic should be avoided. This call was supported by politicians Mark Rutte, Jan Terlouw, Erica Terpstra, Lodewijk Asscher, and former Sinterklaas actor Bram van der Vlugt, as well as singers, comedians, and other well-known Dutch figures.

Dutch newspapers reported in 2018 on the ongoing polarization of the debate, with demonstrators either for or against the traditional Zwarte Piet. The majority of society rejects the radicalism of violent Zwarte Piet supporters and has become more open to change. Currently, there is a coexistence of Piet with full face paint and those with only a few black strokes on their faces, interpreted as remnants of soot.

De Volkskrant described how some children explain the changes: the Piet are lazier than before because they no longer transport as many packages through chimneys, and therefore, they are not as black. Children recognize Piet through the costume and call them Zwarte Piet, even if they don’t have face paint. A study from Leiden University in 2015 found that children aged 5 to 7 perceive Zwarte Piet as clever, friendly, and significant, associating him more with a clown than with black people.

While the German manufacturer Playmobil offered a set with Zwarte Piet with dark skin in 2018, only the supermarkets Jumbo and Albert Heijn still offered Zwarte Piet as chocolate figures. AH reported that Piet had been adjusted for a few years and no longer had earrings or red lips. Other supermarkets had only sooty Piet or none at all, or the sooty Piet only appeared on advertising posters. In some AH branches, unknown individuals pressed the heads of chocolate Zwarte Piet with their thumbs.

During the arrival of Sinterklaas in November 2018, there were disturbances in various cities. According to the police, Kick Out Zwarte Piet activists peacefully demonstrated and followed the rules. However, in Eindhoven and Rotterdam, for example, they were surrounded and insulted by pro-Zwarte-Piet demonstrators. Objects like eggs or beer bottles were thrown. The mayor of Eindhoven, the liberal John Jorritsma, described it as the very intimidating behavior of a large group of aggressive and unregistered hooligans. Similar incidents occurred in 2022 in Staphorst against Kick Out Zwarte Piet, whose demonstration was ultimately canceled by the mayor, and Amnesty International.

References