- The tonfa, originating in China or Indonesia, is a versatile martial arts weapon.

- Modern police forces in the US and Europe use tonfa batons for crowd control.

- Originally adapted from millstone handles, tonfas are balanced for striking efficiency.

- It is part of Okinawan kobudo and its origins in agricultural tools reflect Okinawan resourcefulness in self-defense.

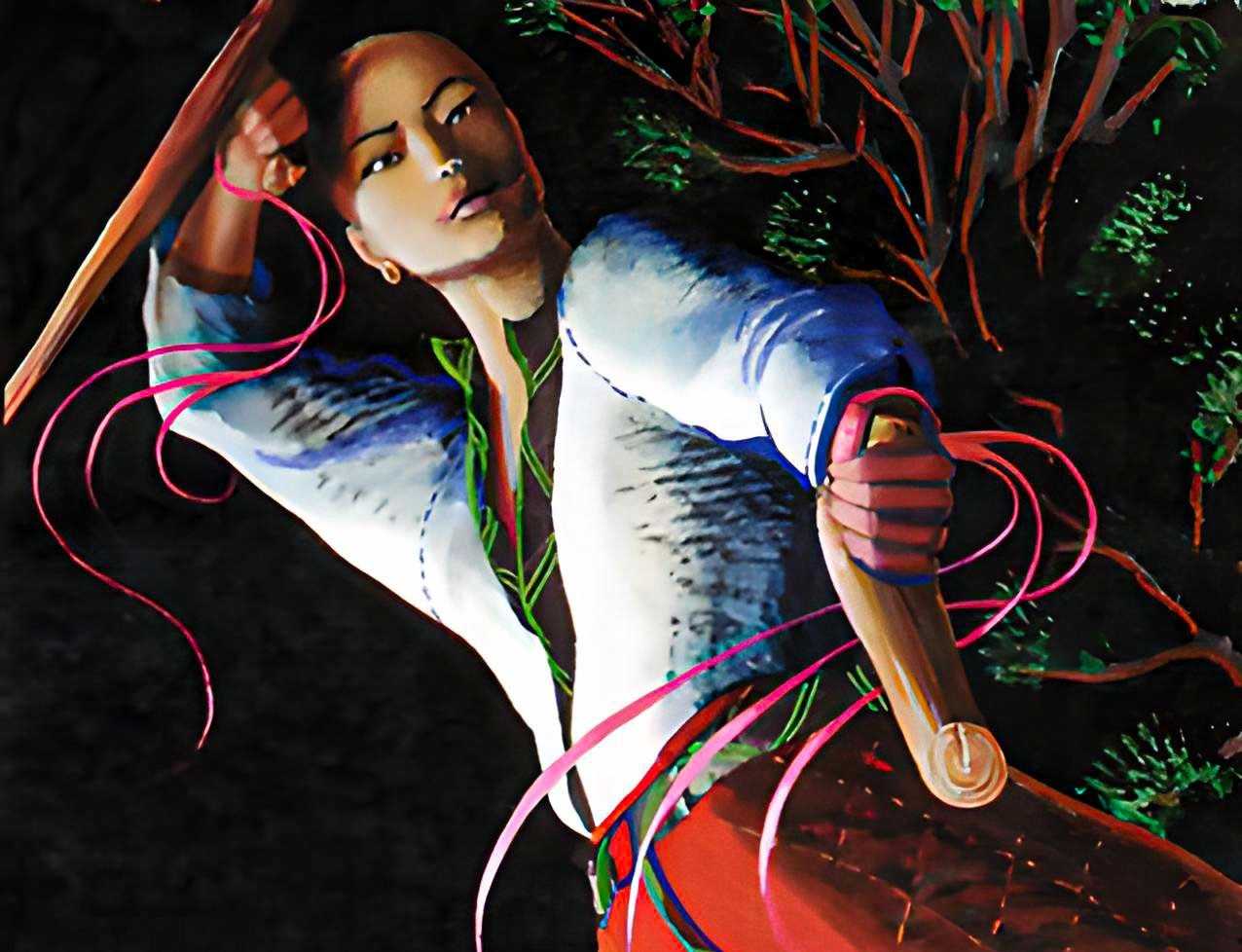

The tonfa is a striking, cold weapon used in martial arts and by the police. It is typically made of wood for martial arts but may also be made of polymer to be used by the police. The tonfa weapon is a 20- to 24-inch (50–60 cm) long stick or truncheon with a handle (tsuka) that is perpendicular to the shaft (yoka). The vertical handle is attached to the shaft around the quarter mark of its length. This ancient martial arts weapon is also body armor in the way it covers the forearm.

| Tonfa | |

|---|---|

| Type: | Blunt object, farm weapon |

| Origin: | Chinese, Ryukyuan, or Indonesian |

| Utilization: | Mostly civilian, seldom military |

| Length: | 20 to 24 inches (50 to 60 cm) |

| Weight: | 1 to 2.2 lb (0.45 to 1 kg). |

This weapon is known as a Tonfa (トンファー), Tuifa (トゥイファー), or Tunkuwa (トンクワァ) in Okinawan Kobudo.

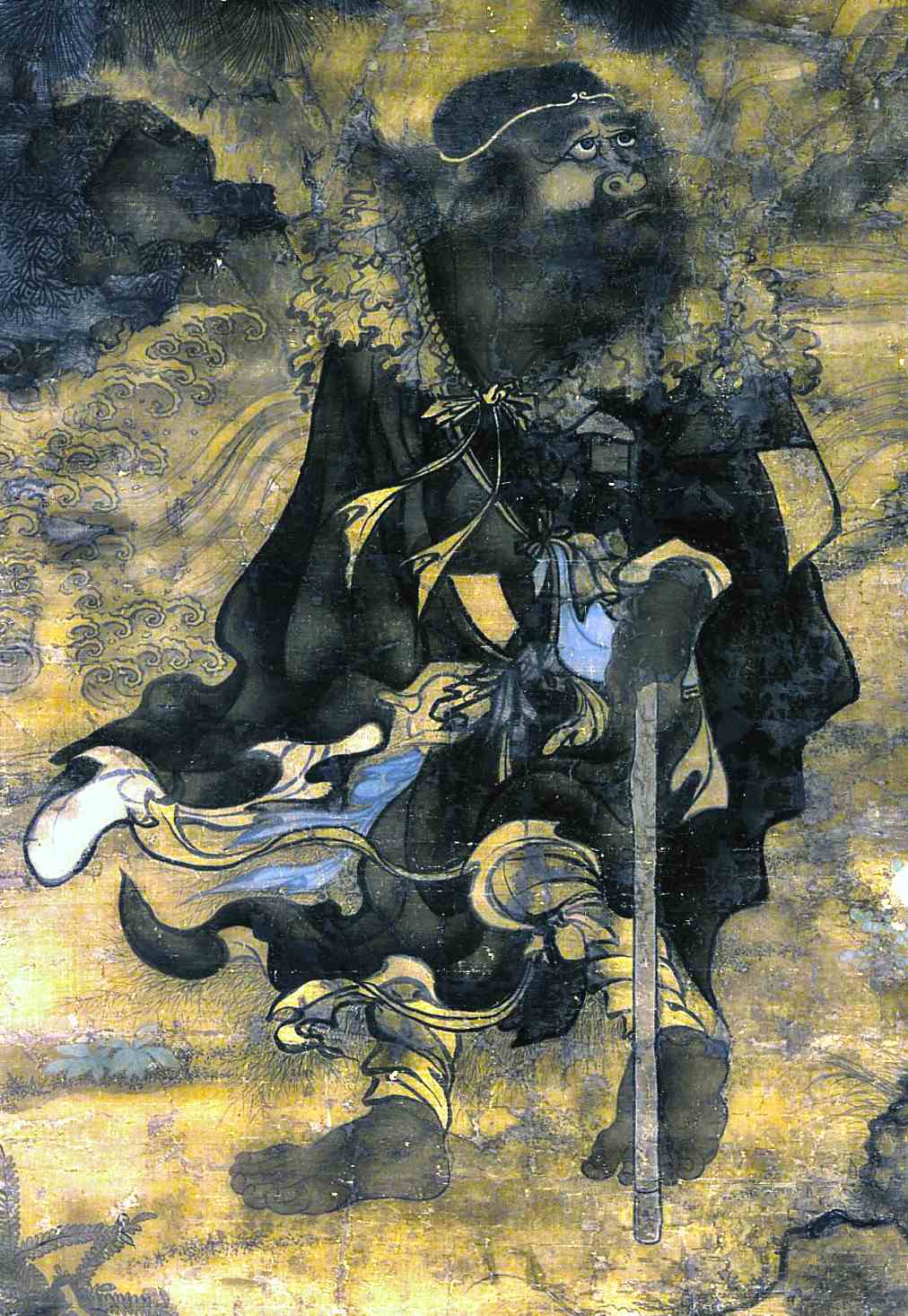

Origin of the Tonfa Weapon

Although there is some debate among experts, most assume that tonfa originated in either China or Indonesia. A hooked sword dating back to the Qin and Han dynasties is credited by certain Chinese authors as the inspiration for this weapon.

Jwing-Ming Yang claims it is only an iteration of a crutch (it is called Kuai, 枴 or 拐, in Chinese which means hanger, crutch, or walking stick).

But two of the most prominent hypotheses propose that the tonfa weapon was either adapted from a Chinese martial technique called sai that was taken to the Ryukyu Islands (“Southwest Islands”) and shrunk into a new weapon or that it was developed from a millstone.

But in the eyes of the Chinese, the origin of the tonfa can also be traced to the crutch. Both of these theories base themselves on a ban on weapons in Okinawa instituted by Shō Hashi (d. 1439) after the island’s civil war inspired the construction of this weapon.

However, it is speculated that these limitations encouraged people to resort to the unusual use of agricultural equipment as weapons. And it is more frequently claimed that the wooden handle of a millstone, a well-liked agricultural tool, served as inspiration for the tonfa.

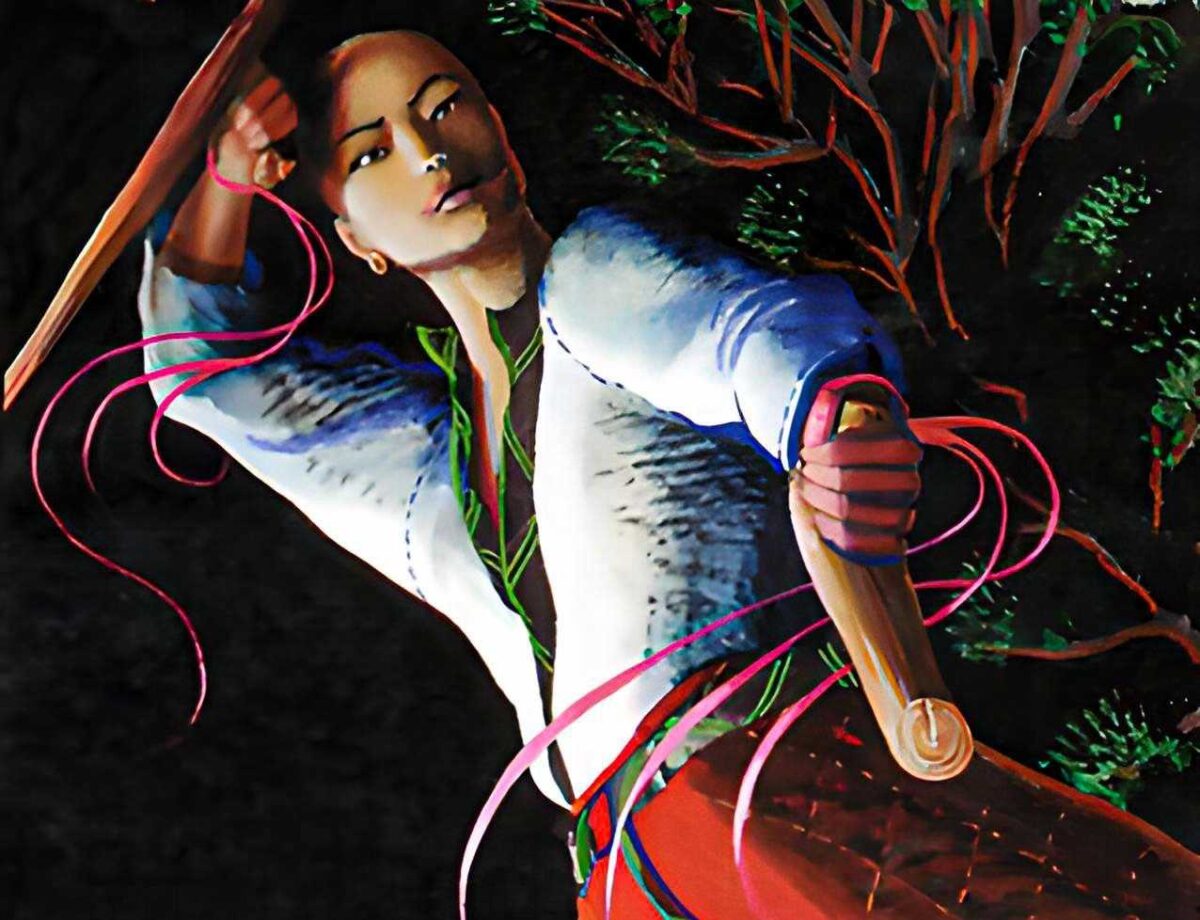

Numerous variants, tonfa-inspired weapons, and characters that wield tonfas can be found in works of fiction like manga and anime today.

How Do You Use the Tonfa Weapon?

In a tonfa, a small vertical handle is affixed to one end of the about 18 to 20 in (45–50 cm) long pole to serve as a grip. These weapons often come in pairs and are held individually. Each weapon weighed from 1 to 2.2 lb (450 to 1 kg).

This weapon’s delicacy lies in the way it balances flexibility with strength, allowing its user to gauge the force of both incoming and outgoing blows. Pairing two tonfas together has proven to be the most effective way to use them. The weapon calls for excellent hand-eye coordination and a steady center of gravity.

Cover your arms and elbows while holding the grip portion (honte-mochi style), block the strikes like in karate, stand your ground, thrust forward, or utilize your free hand or kick.

If you turn the long end of the shaft toward your adversary, you can also use this weapon like a club (gyakute style).

Half-rotating the weapon by turning the wrist allows for rapid switching, and you can also strike your opponent by using the momentum of this rotation.

Furthermore, the grip can also be turned towards the opponent and used in a kamajutsu fashion by handling the shaft (tokushu-mochi style). It’s an attacking and defensive weapon designed specifically for use against sword-wielding foes.

To stop a fleeing person, the “baton throwing” method teaches students to hurl the tonfa in a boomerang fashion toward their legs. This method is highlighted in the 1982 drama series “T. J. Hooker.” Karate was especially responsible for spreading this weapon across the American martial arts community.

History of the Tonfa Weapon

Tonfa (also known as tuifa or tongwa in martial arts) has a long and storied history in Japan, but its modern development is inextricably tied to Okinawa Island, located south of the Japanese main islands.

Tonfa is also one of the Eighteen Arms of Wushu and is widely practiced in southern China and Southeast Asia. This weapon has become well-known outside of Japan because of its innovative design, unconventional method of usage, and exceptional effectiveness in close combat.

King Shō Hashi united the three Okinawan kingdoms under the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1409 and banned peasants and other residents from owning or using weapons out of fear of an uprising. After two centuries, in 1609, the regime once again took the weapons away from the people.

It’s Time to be Imaginative

The ban forced the locals to develop a system of warfare that would enable them to defend themselves against intruders using only their bare hands. Okinawa-te (“Okinawan hand”) was born in this way, and it is the progenitor of karate (kara-te, “empty hand”).

Farmers, however, were also resourceful enough to repurpose common agricultural implements into lethal weapons. Kobudo tradition holds that the tonfa, like most of the weapons it employs, has agricultural origins. The tonfa was originally the handle (crank) of a millstone that was used to grind grains, and the farmers turned it into a fighting tool.

Ryukyu islanders fought Japanese samurai with tonfas, similar to the jo or bo staffs.

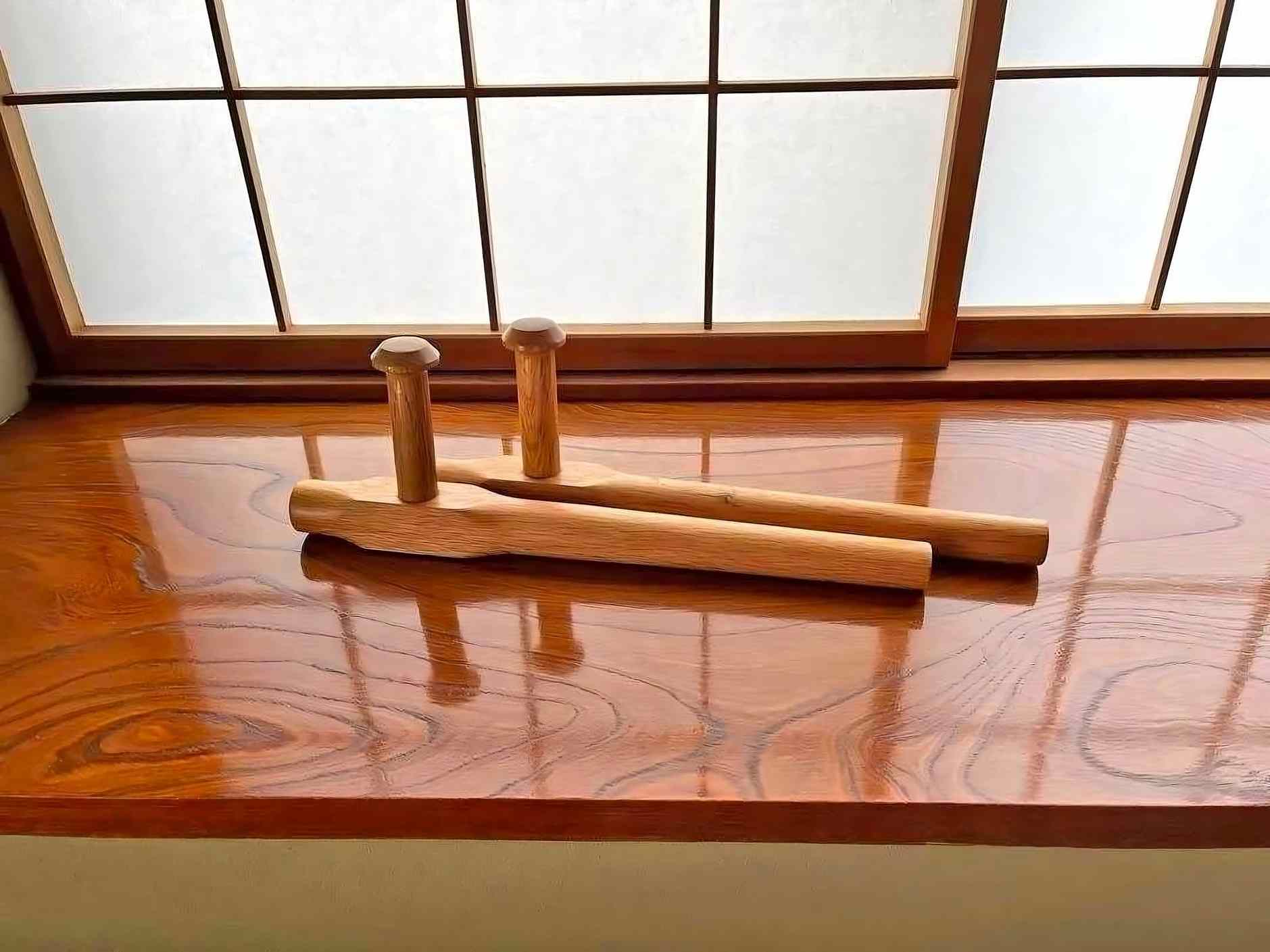

It was simple to remove this crank from the millstone and wield it as a weapon, protecting one’s forearm by grasping it with the yoka (the long portion of the weapon). Lunging with the shorter portion of the shaft, striking with the other end (yoko nage), or rotating the weapon with a quick wrist movement were all common methods of attack.

The tonfa is considered a weapon in Okinawan kobudō (i.e., Ryukyu kobujustu), along with the sai (a weapon with the metal head of a fork) and the nunchaku (a flail weapon).

The territory of the former Ryukyu Kingdom continued to be the main area for the use of the tonfa weapon even after Japan annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1879 and turned it into the Okinawa Prefecture.

Design of the Tonfa Weapon

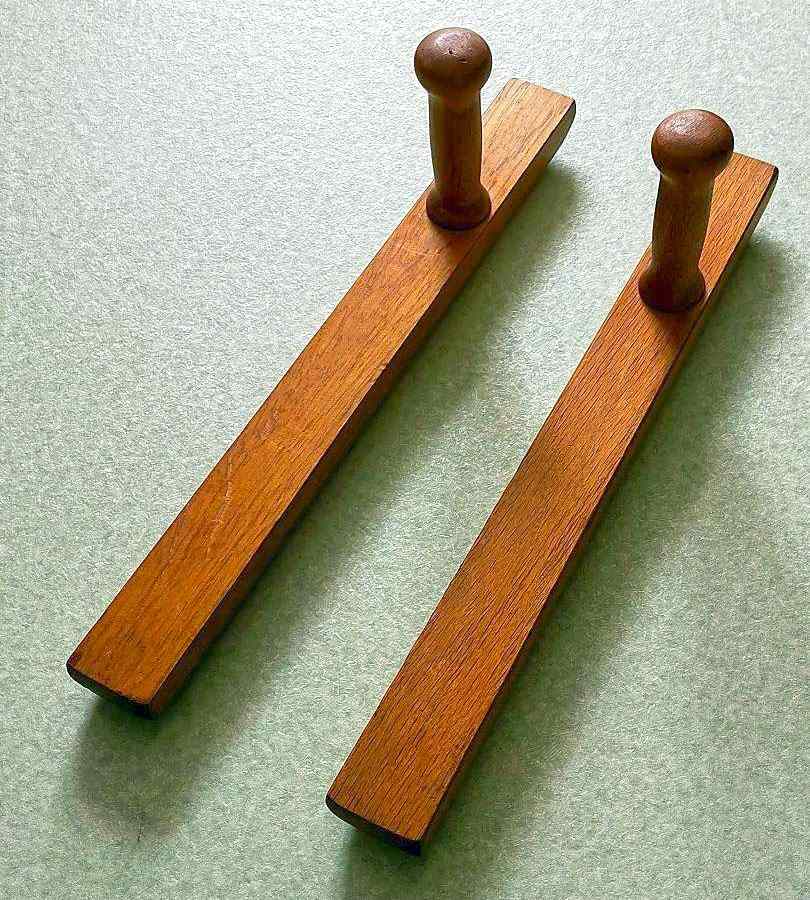

In modern kobudo dôjô, the tonfa weapon has a red wood handle and a circular or square cross-section. It’s 20 in (50 cm) long and has a side handle that’s about a third of the way up.

Different people have different ideal sizes, but once gripped, the weapon should stick out around 1.2 in (3 cm) over the elbow. The cross-section of the weapon is often round, square, or trapezoidal.

When handled improperly or with improvised tactics, the tonfa may cause severe harm or broken bones; hence, it must be treated as a weapon at all times by the law.

Because of the tonfa’s adaptability, law enforcement currently uses it in a number of nations, including Italy, the United States of America, Canada, Finland, Germany, and Switzerland.

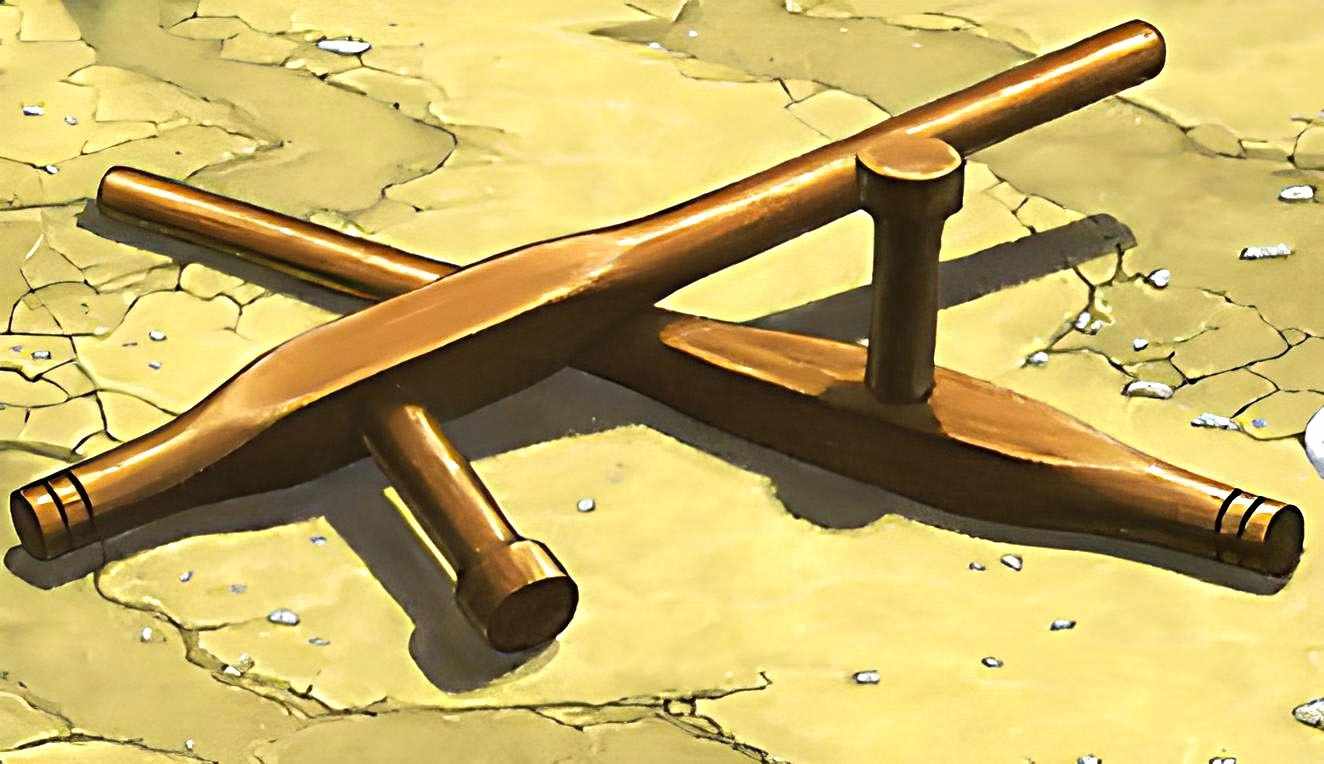

Western Tonfa is Different

As can be seen in the above image, the weapon’s original form is more like a square pillar. However, the weapon’s adaptability led to a cylindrical form in places like the United States and Europe, creating the variant called the “tonfa baton.” When it is used as a baton, it is called a “side-handle baton” or “T-baton.”

Practicing the tonfa necessitates a high level of finger, wrist, elbow, and arm flexibility, strength, and agility in order to achieve a high level of technical proficiency and a certain degree of dexterity.

Tonfa in Popular Culture

Movies and TV Shows

- In Spiritual Kung Fu (1978), Jackie Chan fights a group of monks using more than 6.5 feet (2 m) long staffs, representing the Sixteen Arhats, while wielding a pair of tonfas.

- Diaz – Don’t Clean Up This Blood, a 2012 Italian-French-Romanian historical drama film features the tonfa weapon.

- In the Ninja Turtles: The Next Mutation TV series, Michelangelo uses this weapon instead of the nunchakus he used in previous versions.

- Raphael uses this exact weapon in the TV series Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and it was his boyhood weapon in the comics.

Video Games

- Players of the Left 4 Dead 2 video game get access to the tonfa as a melee weapon option.

- The tone phase is a technique used by Talim in Soulcalibur.

- In Mega Man Zero 3, Zero wields a pair of tonfas with energy blades. By pushing adversaries, breaking certain blocks, and bouncing on the ground, he can go to locations he couldn’t before.

Weapons Similar to the Tonfa

These weapons below share at least a few characteristics with the tonfa weapon:

- Police baton: A police officer’s baton is a cylindrical weapon used for self-defense and to subdue offenders. It has a side handle, designed like a tonfa for improved grip and control. A typical kind of baton used by law enforcement is the PR-24, which is longer and has a side handle.

- Yawara stick: A short, portable weapon used for striking and joint locking, the yawara stick is often constructed of wood or metal.

- Nunchaku: Two sticks are linked together with a chain or rope to form this ancient Okinawan weapon known as nunchaku.

- Sansetsukon: A sansetsukon is a three-section staff that looks like a tonfa but has two extra prongs. It’s a common component in many forms of martial arts.

Martial Art Schools That Use the Tonfa

- China: Shaolin Temple, Sun Bin Quan, Pak Mei Pai, etc.

- Japan and Ryukyu: Karate (especially early Karate known as “Tang Soo Do”), Ninjutsu schools.

- Thailand: Traditional Muay Thai style

- Philippines: Arnis, the traditional martial arts of the Philippines.

Tonfa as Police Equipment

Many martial arts professionals from Okinawa have come to the United States as part of the various waves of immigration from Asia. They were especially Japanese karate practitioners. The American police utilized a cylindrical stick called a tanbo (a type of jo or bo staff) of 25 in (65 cm) in length, 1.2 in (3 cm) in diameter, and 1.1 lb (500 g) in weight until the 1970s.

Some police officers modified their standard-issue baton by adding a side handle to the middle third of the baton using a hexagonal screw, drawing inspiration from the tonfa used in Okinawan kobudo training.

Thus, the first police tonfa baton was created, but its whole construction had to be rethought to reveal its full potential. And unlike the original version used in kobudo, the baton was not intended to be employed in pairs.

Police tonfa designers responded by mandating a new covering made of lightweight, shock-absorbing materials. The United States police agency settled on a polycarbonate alloy covering a 24 in (60 cm) long pole that was injected in a single piece and weighed about 1.5 lb (700 g) after extensive testing and trial and error.

The United States’ police forces emphasize defensive tonfa skills against bladed weapons, with a concentration on disarming the opponent. For those without martial arts training, the technique of temporarily releasing the hold and spinning the weapon to attack is commonly overlooked.

In the United States and Europe, the tonfa baton is an offensive and defensive weapon used to quell riots and incapacitate attackers. Striking, thrusting, sweeping, and grappling are just some of the many methods that can be mastered with this device, which leads many to feel it is very practical and efficient.

Laws and Enforcement

In the United States, carrying a tonfa or any other weapon on duty requires training from a law enforcement organization. For instance, the Monadnock Baton PR-24 STS is listed as the standard baton in the New York City Police Department’s Patrol Guide section “204-09 16 ‘Baton (Side Handle),” and only properly trained personnel who have graduated from the police school are permitted to carry them.

The material also specifies the following details:

- Police officers employed after December 1988 may only carry PR-24 STS.

- Police officers employed by December 1988 and not trained in tonfa are permitted to carry straight batons no longer than 24~26 inches and 1.5 inches in diameter.

- The straight baton may be made out of either false acacia, hickory, American holly, or rosewood.

- Even for those qualified to carry a straight baton, individuals who have received tonfa training at the police academy must carry a tonfa.

The tonfa is a category D weapon in France. Without proper paperwork and a valid reason, you can’t carry this weapon there, just like in Germany. Since the ordinance of 2000 did not permit the concealed carry of firearms by municipal police, telescopic batons remained illegal until 2013. When on duty, French police officers must get special permission to use this weapon instead of the more common truncheon. Because the weapon is considered dangerous, particularly for the head.

Due to its association with shock-crushing cold weapons, the use of tonfa in combat or self-defense is also illegal in Russia. The German Bundeswehr (armed forces) and police have long used this martial arts weapon in the baton role.

A Shift from Tonfas to Batons

Police officers still frequently use tonfas today. However, there has been a shift in recent years toward telescopic batons, which are both easier to hide and more convenient to carry. The aim is to strike fear into the hearts of its potential victims with the mere sight of the weapon.

Another factor is the public’s growing mistrust of law enforcement as a result of high-profile episodes of police brutality, such as the “Rodney King beating” that prompted the Los Angeles riots and similar occurrences around the United States.

Since 2007, the Los Angeles Police Department and other agencies have begun using the Pelican Light 7060 Tactical Flashlight, a handheld, small, high-intensity illumination device measuring only around 8 in (20 cm) in length, instead of the flashlight formerly used for nighttime patrols.

The preceding “Streamlight” and “Maglite” tactical weapon lights were also strong blunt weapons, inspiring the same mistrust as the tonfa, and thus they were phased out. The current generation of flashlights is not designed to be used as a blunt weapon, but their bright beams of light may briefly incapacitate targets like would-be attackers.

The martial arts tonfa is often crafted from red oak and other similarly thick and durable woods. However, law enforcement personnel frequently use batons made of synthetic materials, such as polycarbonate and particular metals, that offer exceptional impact resistance.

References

- Tonfa – Karate Weapon of Self-Defense by Fumio Demura, 1982.

- Classical Weaponry of Japan Special Weapons and Tactics of the Martial Arts by Serge Mol, 2003.

- Weapons & Fighting Arts of Indonesia by Donn F. Draeger – 2012.

- The Ultimate Weapons Manual with Grandmaster by Ted Gambordella Master all the Martial Arts Weapons by Ted Gambordella, 1998.