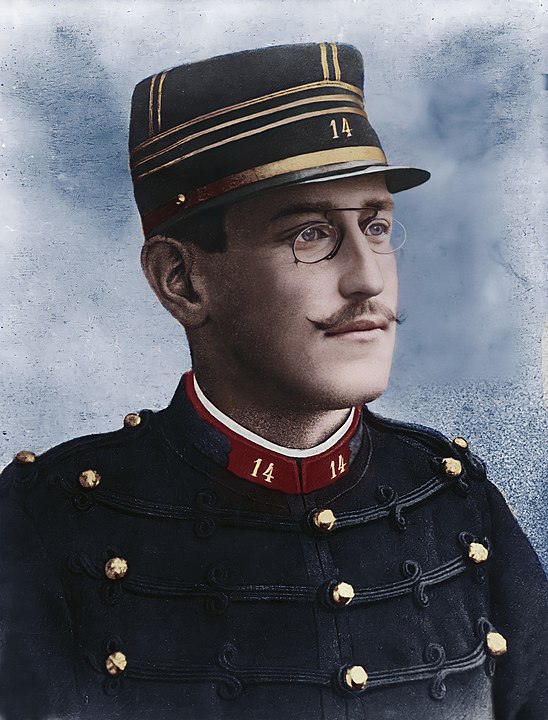

Revealing the profound ideological and political divisions of pre-1914 France, the Dreyfus Affair triggered a severe political crisis that, from 1896 to 1899, caused a deep split in public opinion. It all began on October 15, 1894, when Captain Alfred Dreyfus, of Alsatian and Jewish origin, was arrested at the Ministry of War. Military authorities accused him of transmitting military secrets to the German embassy.

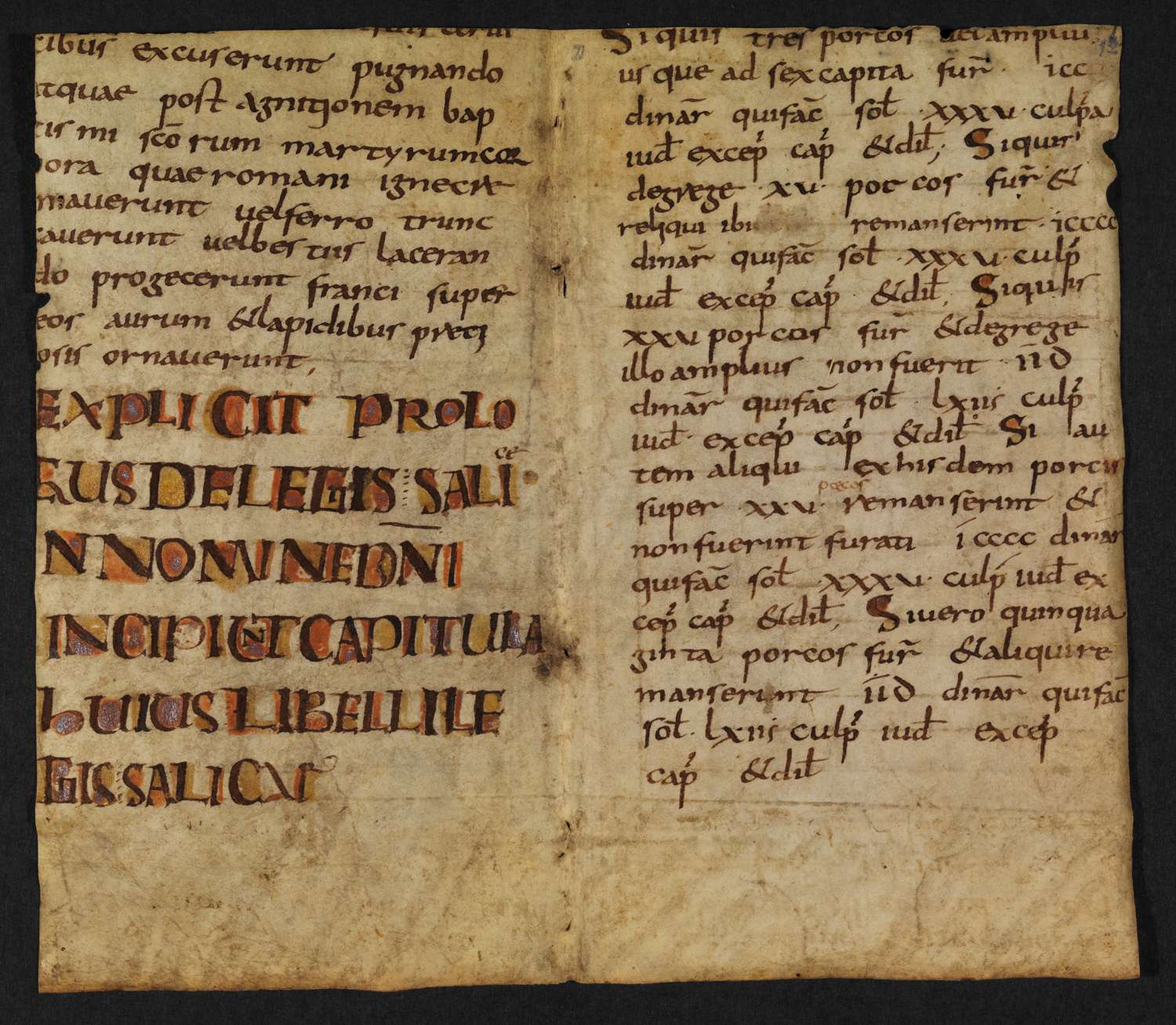

They relied on writings (the infamous bordereau), the graphological analysis of which supposedly concluded that they were penned by Dreyfus. Let’s delve into a judicial error that shook the fledgling Third Republic.

—>The Dreyfus Affair had lasting consequences, including increased awareness of anti-Semitism, changes in French military procedures, and a reevaluation of the relationship between the state and religion. It also highlighted the importance of a fair and transparent judicial system.

The Dreyfus Affair

On the eve of the Dreyfus Affair, France, still reeling from the humiliating defeat of 1870 and the loss of Alsace-Lorraine, which led to the downfall of the Second French Empire, sought solace in the sanctification of the army—a staunch defender against the German enemy and protector of institutions. Espionage was rampant. In late September 1894, a cleaning lady discovered pieces of a memorandum in the waste bin of Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, a military attaché at the German embassy. The memorandum had been written by a French officer who was about to depart for maneuvers.

Swiftly, suspicions fell upon Captain Alfred Dreyfus, an Alsatian of Jewish origin.

In December 1894, following an extensive investigation led by General Auguste Mercier, the Minister of War, Alfred Dreyfus was brought before a military tribunal. Despite the weakness of the evidence presented by the prosecution, including graphological analyses, the captain became a victim of a revanchist and anti-Semitic political atmosphere. This was evident in the reactions of the Parisian crowd during his degradation: “Down with the traitor, down with the Jew!” He was ultimately sentenced to degradation and deportation to Guyane.

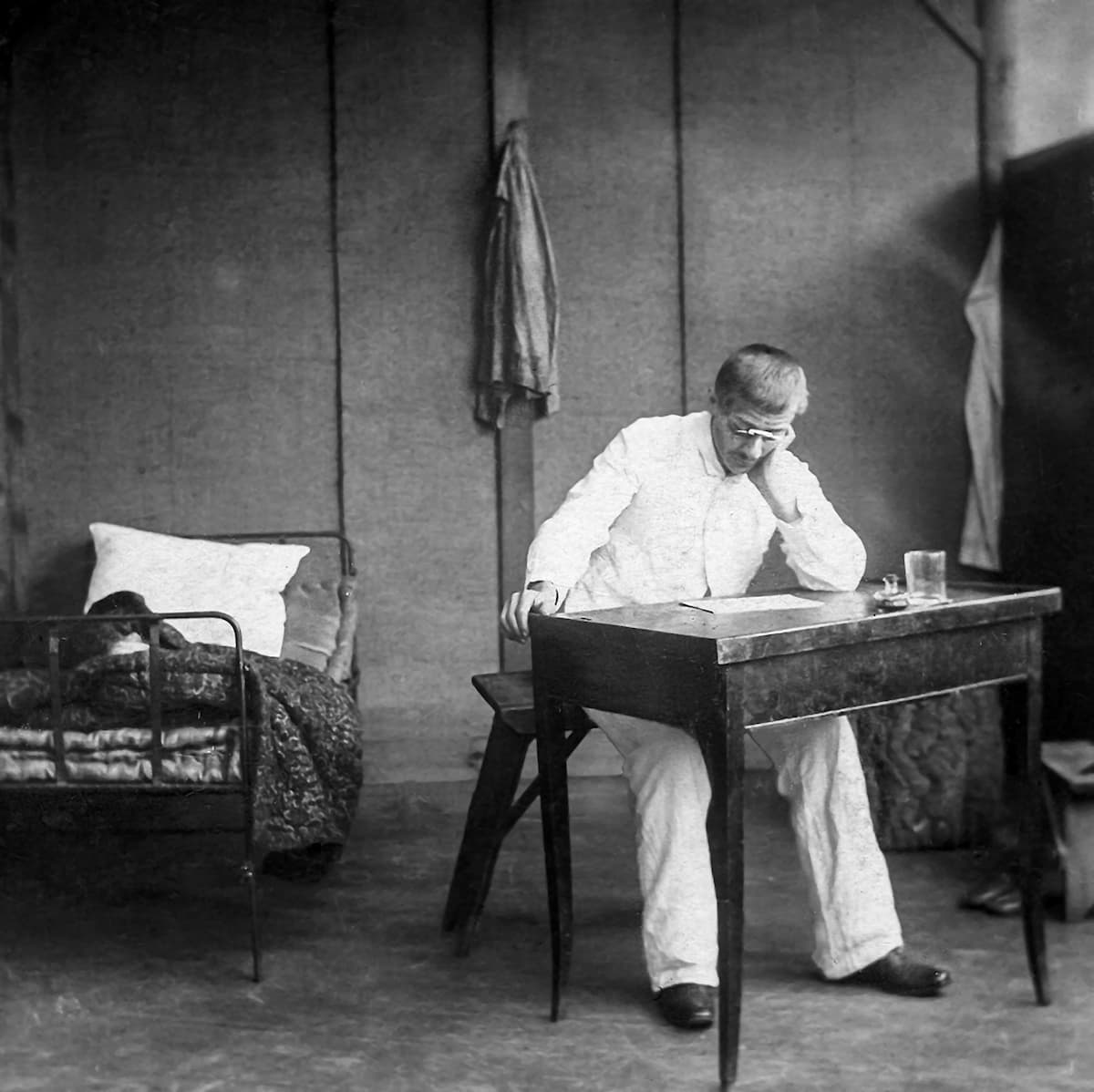

Deported off the coast of Guyane and held in secret, Dreyfus endured the horrors of the penal colony, his health deteriorating rapidly. His case returned to the spotlight with revelations by the new Chief of Intelligence, Lieutenant Colonel Picquart. In early 1896, Picquart intercepted a document authored by Commander Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, associated with the German embassy, featuring handwriting identical to that of the memorandum.

Dismissed by the military high command to whom he reported his findings, Picquart, despite being instructed to remain silent, eventually reveals the truth to Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, an Alsatian politician, and a close associate of Clémenceau. Initially reluctant, Scheurer-Kestner becomes an advocate for Dreyfus with the authorities.

After Mathieu Dreyfus, the elder brother of Dreyfus, filed a complaint, Esterhazy faced trial by the end of 1897. Despite mounting evidence against him, Commander Esterhazy was acquitted in January 1898—an outcome celebrated by nationalist circles but vehemently contested by the emerging “Dreyfusards.”

Public Opinion Fractured Between Two Camps

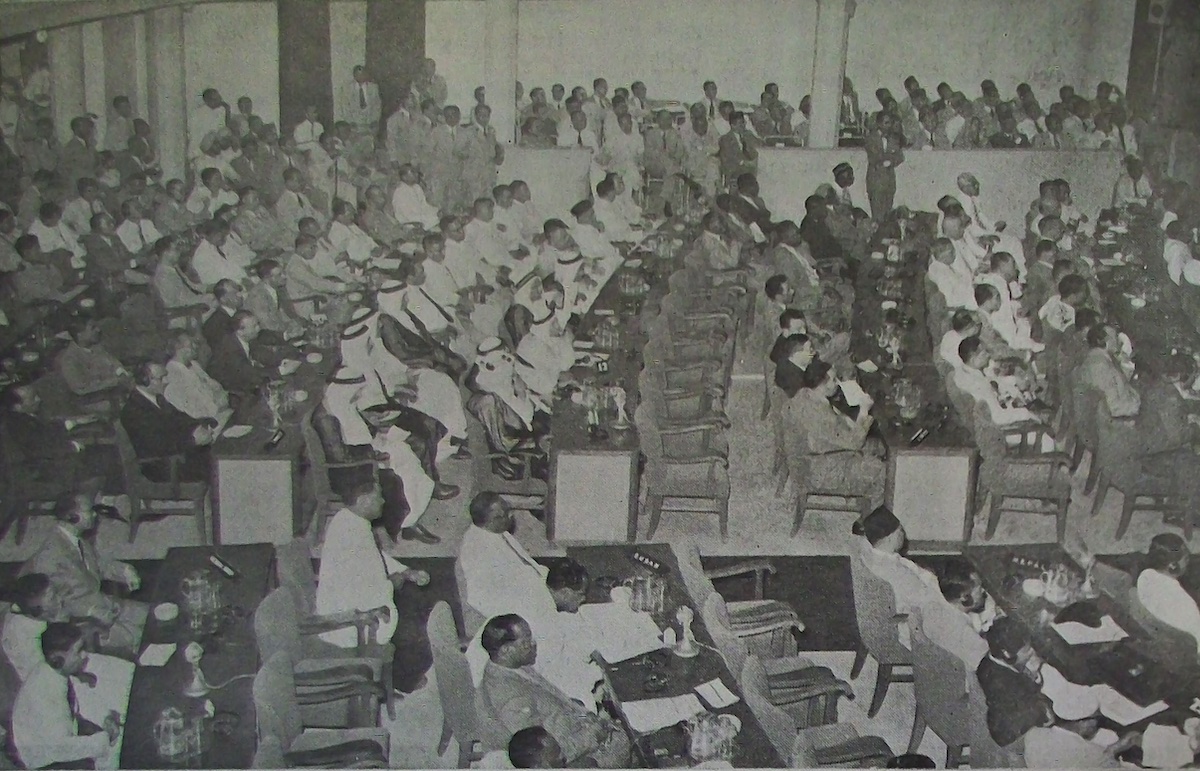

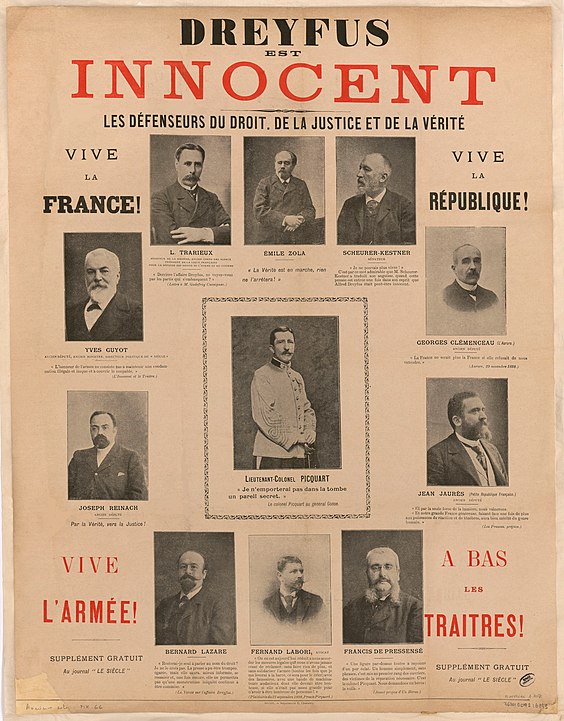

The opinions were divided into two camps: the Dreyfusards, who called for a revision of the trial, and the Anti-Dreyfusards, or Anti-revisionists. Intellectuals were involved. Senator Ludovic Trarieux established the League of Human Rights. Jules Lemaître and François Coppée responded by creating the French Homeland League. Two value systems clashed.

The anti-Dreyfusards were unwilling to question the legal decision or doubt the military. This was seen as essential for the integrity of the nation and the maintenance of social order. According to them, the revisionists embodied anti-France. They even absolved Colonel Henry of being the author of a “forgery” to support the official thesis (Henry eventually committed suicide). This denial of the facts stemmed from a new, antipositivist mindset.

In contrast, the Dreyfusards, by condemning the actions of some officers, claim not to harm the army and present themselves as true patriots and guardians of the traditions of the French Revolution. They advocate for the defense of the individual, fight for justice, with France having the mission of “being the teacher of law for Europe,” and criticize the alliance of the “sword and the crosier,” as the Church, for the most part, sided against Dreyfus.

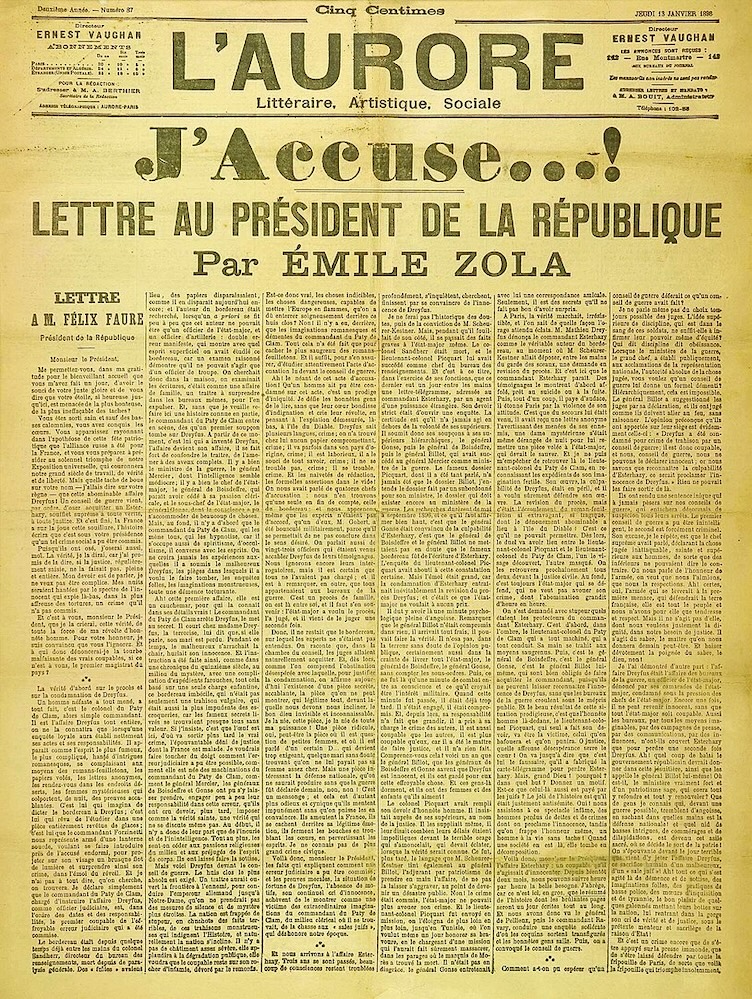

Émile Zola’s Open Letter

The “Dreyfusards” were led by the writer and journalist Émile Zola. In his article “J’Accuse…!” published in the newspaper L’Aurore on January 13, 1898, Zola appealed to President Faure, denouncing the injustice done to Dreyfus. The captivatingly titled article achieved significant success, selling 300,000 copies within hours. As Charles Péguy noted, the impact was so extraordinary that Paris almost turned on itself. The Dreyfus Affair sparked a nationwide public debate in France, giving rise to fratricidal passions. Anti-Semitic riots, particularly in Algiers, disturbed the country, and the Third Republic momentarily appeared to waver.

In response to this turmoil, authorities overturn Dreyfus’s initial verdict, and the captain returns to the mainland for his second trial. Once again, justice exhibits rare partiality by condemning the accused, this time to ten years in prison, allegedly with mitigating circumstances. On September 19, 1899, ten days after the verdict, President Loubet pardoned Dreyfus, a way of finally delivering justice without losing face.

The Annulment of the Judgment and the Rehabilitation of Dreyfus

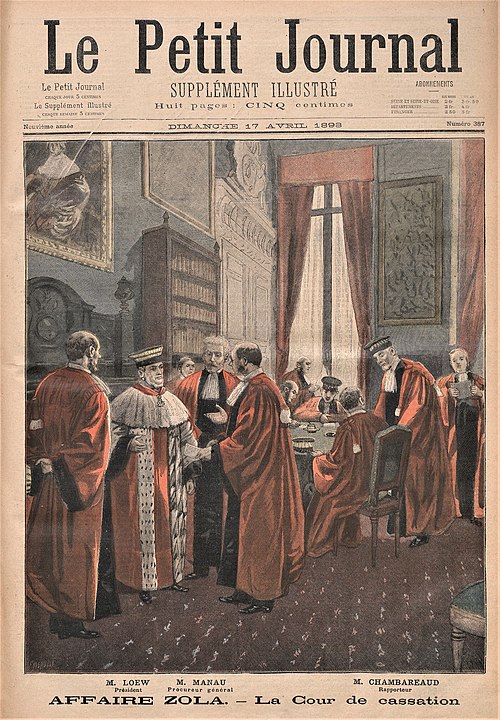

The legal resolution of the Dreyfus Affair occurred only in 1906, when the Court of Cassation overturned the verdict of the military tribunal in Rennes, acknowledging that Dreyfus’s conviction was “wrongly” pronounced. The true culprits, including Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, who was in exile in the United Kingdom, were never condemned. Dreyfus, reinstated in the military, served his country during World War I and rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

Alfred Dreyfus passed away in 1935, and there was a time when the idea of transferring his ashes to the Panthéon alongside the illustrious advocate of his cause, Émile Zola, was considered.

Chronology of the Dreyfus Affair

October 15, 1894: Arrest of Captain Dreyfus

General Mercier, Minister of War, orders the arrest of French Captain Alfred Dreyfus. The officer is accused of providing confidential military information to Germany. He will be charged based on a mere resemblance of handwriting on a document found at the German Embassy in Paris. Behind this accusation lies another reality, a religious one, as Captain Dreyfus came from an Alsatian Jewish family.

This seemingly ordinary espionage story will lead to one of the most serious political crises of the Third Republic, becoming known as the “Dreyfus Affair” and dividing France between Dreyfusards and Anti-dreyfusards.

December 22, 1894: Dreyfus Pronounced Guilty

Alfred Dreyfus is sentenced to life imprisonment for espionage in favor of Germany. He was sent to Devil’s Island in Guyane on January 21, 1895. His conviction triggered an ideological battle in France between “Dreyfusards” and “Anti-dreyfusards” when intelligence chief Commander Picquart requested a retrial in 1898. Captain Dreyfus’s condemnation becomes the infamous “Dreyfus Affair.”

January 5, 1895: Dreyfus’s Degradation

Condemned to life imprisonment, Dreyfus undergoes a humiliating procedure: he is degraded in the grand courtyard of the Saint-Cyr military school in Paris during a parade. An engraving immortalizes this procedure and is circulated in French newspapers. Military justice believes it will put an end to the Dreyfus affair by showing firmness against those who betray the Fatherland.

However, a victim of an unfair trial where he and his lawyer couldn’t even see all the evidence against him, Alfred Dreyfus, proclaims his innocence. People who want to know the truth will bring up the affair again in 1896.

June 4, 1898: Foundation of the League of Human Rights

Against the accusations of Dreyfus and Zola in the same affair, a new social concept emerges for intellectuals. They gathered in January 1898 to defend the Dreyfusard cause and establish the “League for the Defence of Human Rights.” Banned under Vichy France, the LDH was later reformed and still exists.

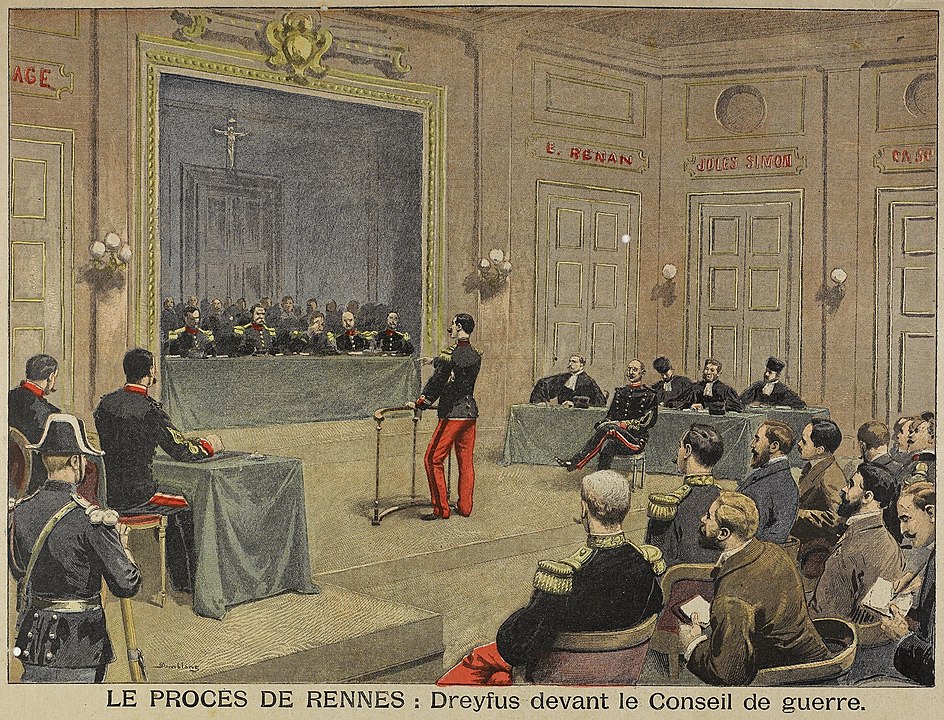

June 3, 1899: Opening of the Second Dreyfus Trial

The Court of Cassation having finally overturned the 1894 judgment, the military court must again judge Alfred Dreyfus, this time in Rennes. Dreyfusards are optimistic about the trial’s outcome, believing that the truth is already known: according to them, Dreyfus will be acquitted and recognized as not guilty of treason. Moreover, the climate in France is dire, and anti-Semitic leagues, now very virulent, are prohibited.

To avoid a nationalist coup, Waldeck-Rousseau had indeed ordered arrests, including the challenging arrest of Jules Guérin. But to everyone’s surprise, the trial will continue and once again incriminate Dreyfus.

September 9, 1899: Dreyfus Again Convicted

The verdict of Dreyfus’s second trial shatters the hopes of the Dreyfusards: the military officer is declared guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison. It was a perplexing sentence for many observers, but the judges granted him mitigating circumstances to reduce his sentence.

Antidreyfusards rejoice while condemning this leniency. In a climate close to nationalist insurrection, the judgment seems political: a compromise to save the honor of the state and the army. Ten days later, under the advice of Waldeck-Rousseau, President Émile Loubet pardons Dreyfus.

September 19, 1899: Dreyfus Pardoned

Following the advice of his Prime Minister, Waldeck-Rousseau, President Émile Loubet pardons Alfred Dreyfus, who had been sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment just days before during the revision of his trial. The French officer, wrongly accused of divulging military information to the German army during the 1870 war, had been sentenced to life deportation on Devil’s Island in Guyane in December 1894.

The mobilization of Dreyfusards, notably Émile Zola, had led to his retrial. The day after the presidential pardon, Alfred Dreyfus is released. The five-year-long “affair” that divided France comes to an end.

March 5, 1904: The Court of Cassation Accepts the Request for the Revision of the Dreyfus Trial

Alfred Dreyfus’s efforts for his rehabilitation achieved an initial victory in French justice. The Court of Cassation, known for its independence, agrees to review the Dreyfus case to potentially overturn the Rennes judgment of 1899 and request a retrial. A year and a half later, the judgment will indeed be overturned without a retrial being requested; Dreyfus will be officially rehabilitated.

July 12, 1906: Rehabilitation of Captain Dreyfus

Stripped of his position as captain in the French army in 1894 on suspicion of disclosing military secrets to Germany, Alfred Dreyfus is rehabilitated by the Court of Cassation in Rennes. After serving five years of penal labor in Guyane, he was declared guilty of high treason in 1899 and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

However, all evidence attests to his innocence and the guilt of another officer, Commander Esterházy. Pardoned by President Émile Loubet in September 1899, Alfred Dreyfus is reinstated in the army with the rank of battalion chief and decorated with the Legion of Honor.

October 26, 1906: Georges Clemenceau Assumes the Presidency of the Council

The Minister of the Interior forms a cabinet that includes René Viviani as Minister of Labor and General Picquart, who distinguished himself in the Dreyfus affair, as Minister of War. Georges Clemenceau retains the Ministry of the Interior. Internationally, he stands out, among other things, by maintaining peace with Germany while reforming the army to be prepared for any conflict.

June 4, 1908: Émile Zola Enters the Pantheon

Six years after Émile Zola’s death, his ashes were transferred to the Pantheon. This decision, desired and voted for by socialist deputies, triggered violent reactions from the nationalist right. They still reproach Zola for his involvement in the Dreyfus affair, especially through his letter “J’accuse,” and unleash a torrent of hateful insults against the writer and journalist, the left, and Dreyfus. Moreover, the latter is the victim of an assassination attempt by a journalist from “Le Gaulois,” while anti-Semitic demonstrations punctuate