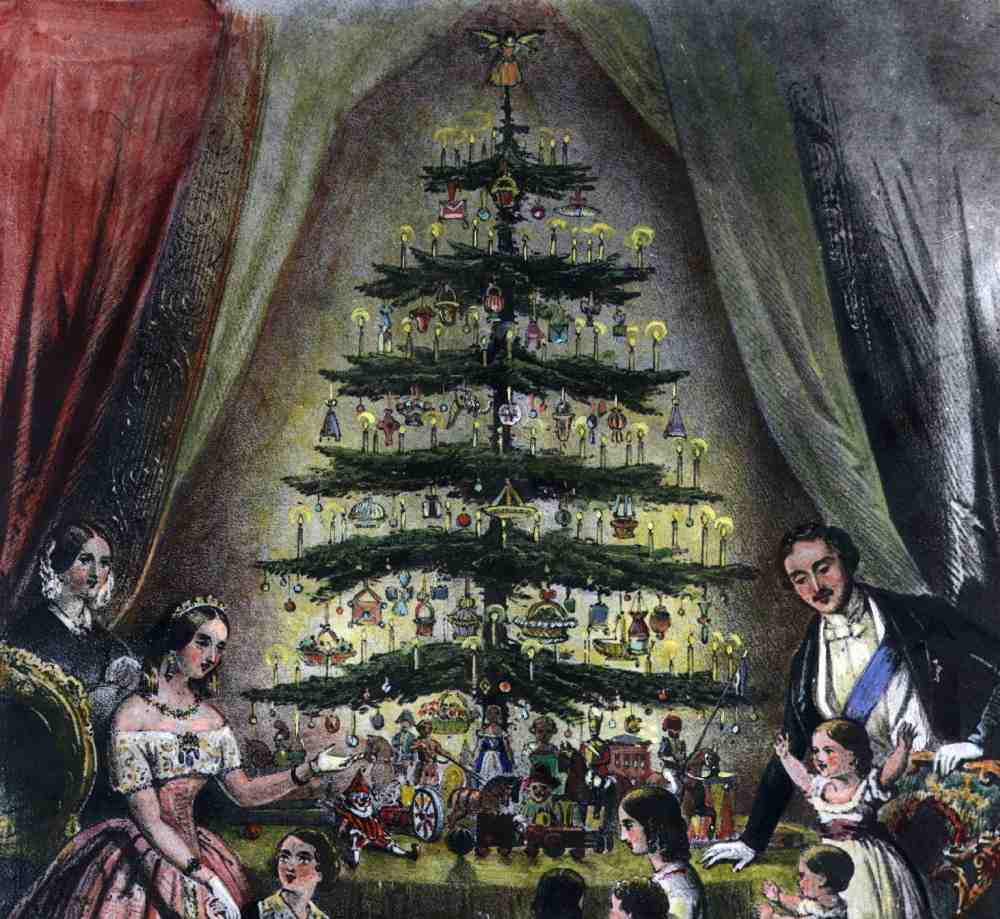

Yes, there is no mention of a Christmas tree in the narrative surrounding Jesus’ birth. And the early Christmas trees did not appear until the 15th century. When Martin Luther and other reformers claimed the Christmas tree for the Protestants, the Nativity scene had hitherto been associated with Christmas only in the Catholic tradition. The habit of adorning the home with evergreens is traced to the Germans, and it finally spread to the United States in the 1830s. The custom didn’t fully take off until German Prince Albert offered one to his wife, Queen Victoria of England. Royal fever was propagated through illustrations of the couple in 1848 in front of a Christmas tree.

Christmas tree has been around for at least 4,000 years

The Christmas tree custom, which has been around for at least 4,000 years, has its roots in Northern Europe, notably among the Celts. This is due to the Samhain festival of the Celts which is at least 4,500 to 5000 years old. The winter solstice represented the sun’s rebirth and renewal, hence its symbolism was significant. In the past, on December 24, it was usual to adorn the Christmas tree with edible items like fruit and ears of wheat. In order to compete with this pagan event, the Christian Church in the 4th century decided to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ on the same day.

The Celts attributed a tree to each month of the year, and December’s tree was the one they identified with the celebration of the winter solstice. This custom predates Christianity by at least 2,500 years. In the 11th century, men used red apples as a garnish to represent the heavenly realm of Christianity. In Europe, an ordinary festive tree first made its appearance in Alsace, France, in the 12th century. The tree was given the moniker “the Christmas tree” only for the first time in 1521. Apples, chocolates, and miniature cakes were placed within, and the star of Bethlehem was carefully placed atop the tree as a symbol of the celebration.

Was the first Christmas tree a palm tree?

Probably not but the Christmas tree’s Arabic origin appears in the Koran in a passage with Maryam (or Mary), where she is astonished by childbirth pangs and rests against a tree. Arabic for “Jesus” is “Isa,” and he is born beneath a (Christmas) tree in this story. But this tree wasn’t your average tree; it was a palm tree.

The Pagan origin of the Christmas tree

The Christmas tree is an ancient custom and it seems likely that the modern Christmas tree has its roots in a more Pagan observance. Pagan people traditionally welcomed winter into their houses at the time of the winter solstice. These living, verdant branches were thought to ward off evil winter spirits while also promising safety and fruitfulness.

The custom of putting up a Christmas tree and decorating it dates back to ancient pagan customs. An evergreen tree was decked up with paper ornaments, candles, fruit, and nuts at the time. For this purpose, apples were employed more than any other fruit.

The Christmas tree also dates back to Saturnalia in ancient Rome when the Romans celebrated their god Saturn. In order to celebrate the arrival of spring at the winter solstice on 17–23 December, Pagan Roman families always brought their homes evergreen branches and adorned trees which later became the base of today’s Christmas tree.

Many of the customs we identify with Christmas originated in Saturnalia festivities which also originated in Pagan traditions such as candles, dancing, eating, wreaths, and gifts.

The Romans were familiar with the practice of using green branches to mark the New Year’s Eve celebration, since they did it themselves during the Kalends (the Roman New Year festival) by decorating their homes with laurel.

Evergreen branches were also utilized as a symbol of perpetual life when the Druids, ancient Celtic priests, decorated their temples in Northern Europe. As the “barbaric” Vikings venerated Balder, the sun god, evergreen trees were honored throughout Scandinavia.

Ra was a hawk-headed deity in ancient Egyptian religion who was crowned with a solar disk. The Egyptians celebrated the victory of life over death by decorating their dwellings with green palm rushes on the solstice, when Ra started to recover from his curse.

The Christian origin of the modern Christmas tree

An Englishman named Saint Boniface (675-754) traveled to what is now Germany to share the gospel with the native Pagan tribes. The great tree known as Donar’s oak (Thor’s oak), which the new Christians had been worshiping and using for sacrifices, was knocked down by him in 723 or 724 with one mighty blow of his axe. A fir tree sprang from the hole where the tree had split in two.

Because it was a hallowed tree, the Tree of the Christ Child, Saint Boniface explained to the villagers that it held the promise of eternal life. Then, on Christmas, Boniface instructed them to bring a fir tree from the woods into their homes and adorn it with gifts of love and kindness. The result was the origin of the fir Christmas tree.

In the Middle Ages (between the 5th and 15th centuries), Pagan and Christian beliefs began to blend. Church leaders realized early on that they needed to reach out to illiterate members of the community by representing biblical themes in art. This practice gained momentum throughout the Middle Ages.

Among them all, the myth of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden had long been told. So, a “paradise tree” would be instructive for a paradise setting. It was imperative that this tree be evergreen, thus, a fir tree was chosen. Meanwhile, the red apple in the story was the symbol of knowledge, and therefore, it became an indispensable part of the Christmas tree, even today.

The original tale told around the green tree with the apple was not the Christmas story but rather the story of Adam and Eve and the snake. The “tree of paradise” became associated with the Christmas tale throughout time, and thus it may be seen as the progenitor of the Christmas tree that is now adorned with gifts of candy, cookies, and ornaments made of gold.

It is safe to say that the modern version of the Christmas tree with fir was created by Christians. Above all else, though, the actual Christmas tree is an emblem of expectation in many different faiths.

Fir trees in Germany were the first to be decorated

For the modern history of the Christmas tree, a decorated tree is first referenced in 1419 in conjunction with the bakers’ guild of Freiburg in Germany. Though the tree’s origins are still murky. For instance, 2020 marked the 510th anniversary of the adorned Christmas tree in Riga, Latvia.

Therefore, southwest Germany seems to be the birthplace of the decorated fir tree, which evolved from the practice of keeping evergreen branches inside the home, a Pagan tradition. A local legend claims that the Christmas tree trade took place in Strasbourg as early as 1535.

Candles were not offered, but the little yew, holly, and box trees adorned the parlor walls at the time. In 1570, the ritual spread north to Bremen, where guild houses of artisans hung apples, and nuts on their trees. Children were encouraged to take the edible decorations home and devour them.

The fir as a Christmas tree was popularized in the 19th century

Beginning in 1730, candles were also used to adorn Christmas trees. But initially, only Protestant households decorated trees with lights. During the liberation struggles against Napoleon Bonaparte at the turn of the 19th century, the fir tree became a popular decoration in homes of all faiths. Even non-Christians began to associate the tree with Christmas during this period.

At the tail end of the 19th century, the practice of adorning trees spread across Germany, first to the urban centers and later to the rural areas. Eventually, the Christmas tree made its way throughout Europe, helped by the links of German aristocratic families to other kingdoms.

Although the tradition of decorating a Christmas tree began in Germany, it was made widely known in the 1840s in Britain thanks to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The German Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld was Victoria’s mother, therefore the little princess’s upbringing included a Christmas tree and all the trimmings. When the Illustrated London News released a depiction of the royal family gathered around a Christmas tree at Windsor Castle that year (1848), the practice of adorning an entire tree became more widespread in Britain.

Along with emigrants, German troops who participated in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) also helped spread the Christmas tree across the New World in the 1800s. Washington, D.C.’s first “Christmas Tree” was placed in front of the White House in 1891.

Origin of the notable Christmas trees

The tradition of the “Christmas Tree” spread to the United States in the 19th century. In the United States, the Ellipse to the south of the White House has had a Christmas tree every year since November 1923, when First Lady Grace Goodhue Coolidge (1879–1957) approved the idea and gave the go-ahead to the District of Columbia Public Schools in Washington. The tree was officially dubbed the “National Christmas Tree” by its organizers.

Another well-known Christmas tree has its roots in WWII. It is the Norwegian fir that is displayed annually in London’s Trafalgar Square. Since 1947, London’s Trafalgar Square has featured a Christmas tree that has been sent from Oslo. This event is a tribute to the two nations’ resistance against Nazi Germany.

Similarly, at Christmastime, the Pope and everyone in Rome marvel at the beauty of a massive tree in St. Peter’s Square known as the Vatican Christmas Tree. It is customary to import the tree from a new nation every year.

The glistening Christmas tree even spread to Latin America after World War II. The ones with the means would buy a tree imported from Europe and adorn it with cotton flakes on Christmas Eve in La Paz, the capital of Bolivia.

A Christmas tree is an essential part of the holiday season, bringing delight to both children and adults. And today, towns and cities fight to have the biggest and best Christmas tree in the middle of their biggest square. A clipped tree usually dies within 40 days. But scientists have found a way to increase their life to 75 days.