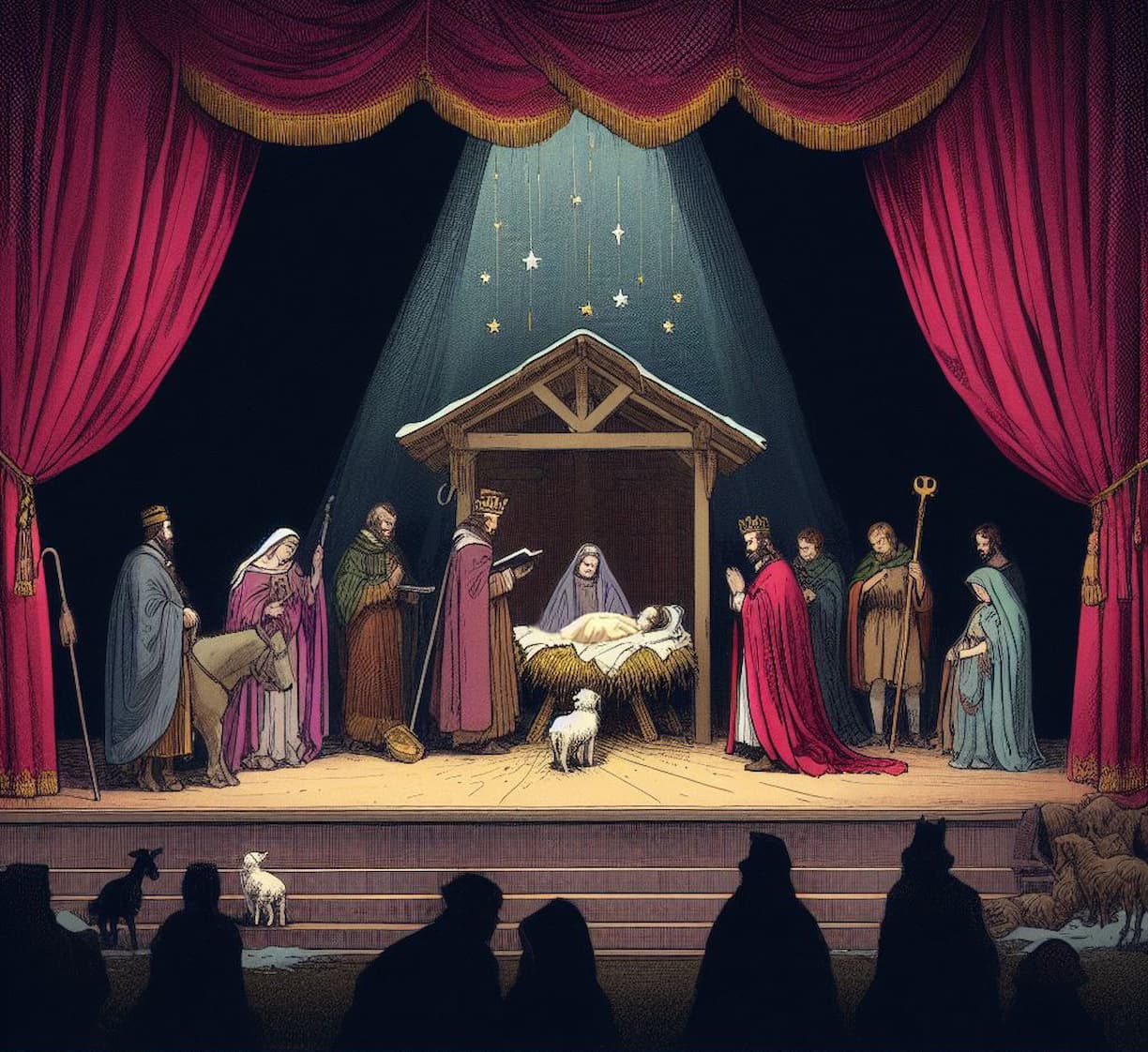

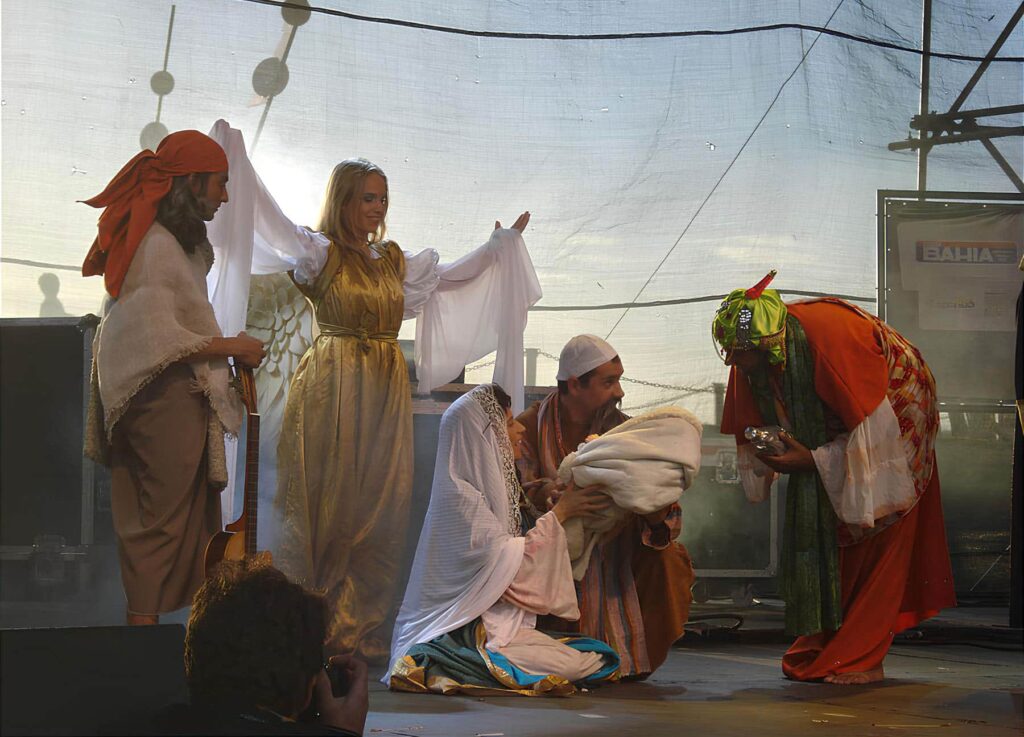

The birth of Jesus Christ is told in a Nativity Play, which is sometimes called a Christmas pageant. During the Christmas season, youngsters usually perform it, and animals and props are sometimes part of the drama, along with human and heavenly characters. The play draws on biblical events as a basis, but it is also free to include apocryphal stories, regional elements, and customs. The Nativity Play is a common practice in Sunday schools and elementary schools with a strong Christian focus.

What is a Nativity Play?

The Nativity Play is a Christian folk custom associated with Christmas. It is a multi-character dramatic play and the most popular Christmas peasant mystery play, also known as a shepherd’s play. The characters include not only the baby Jesus but also witnesses to the birth of Jesus: Mary, Joseph, the Three Wise Men, an angel, shepherds, an ox, a donkey, and a lamb. In this folk custom, two traditions blend: pre-Christian pagan and ancient beliefs, as well as customs stemming from the Christian nature of the celebration. Its name in countries like Hungary originates from the biblical city of Bethlehem. The purpose of this folk custom is to drive away evil spirits with noise by wearing costumes and masks.

Originally practiced in what is now Italy, the practice of staging real nativity scenes eventually spread to other Christian nations. Not only does the Catholic Church uphold this practice, but so do other Christian faiths like the Baptists. Nearly two hundred venues throughout Italy hosted Nativity Plays at the turn of the millennium.

The Beginnings of the Nativity Plays

The Nativity Play or Christmas pageant developed into a spiritual theater that laypeople performed throughout the Middle Ages, with its roots in liturgical Christmas festivities. The nativity scene with the holy family and the infant Jesus Christ was staged at the altar as early as the tenth century.

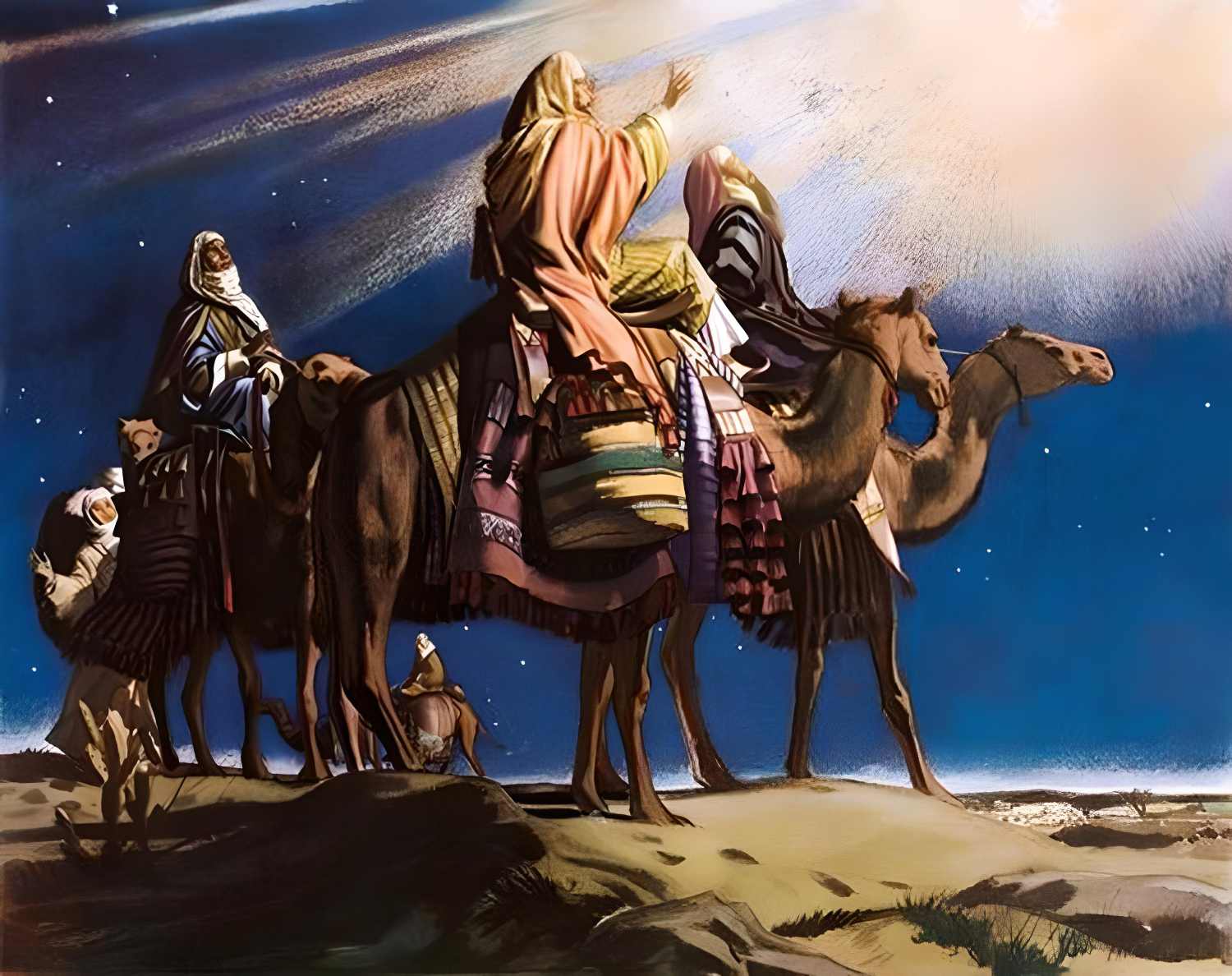

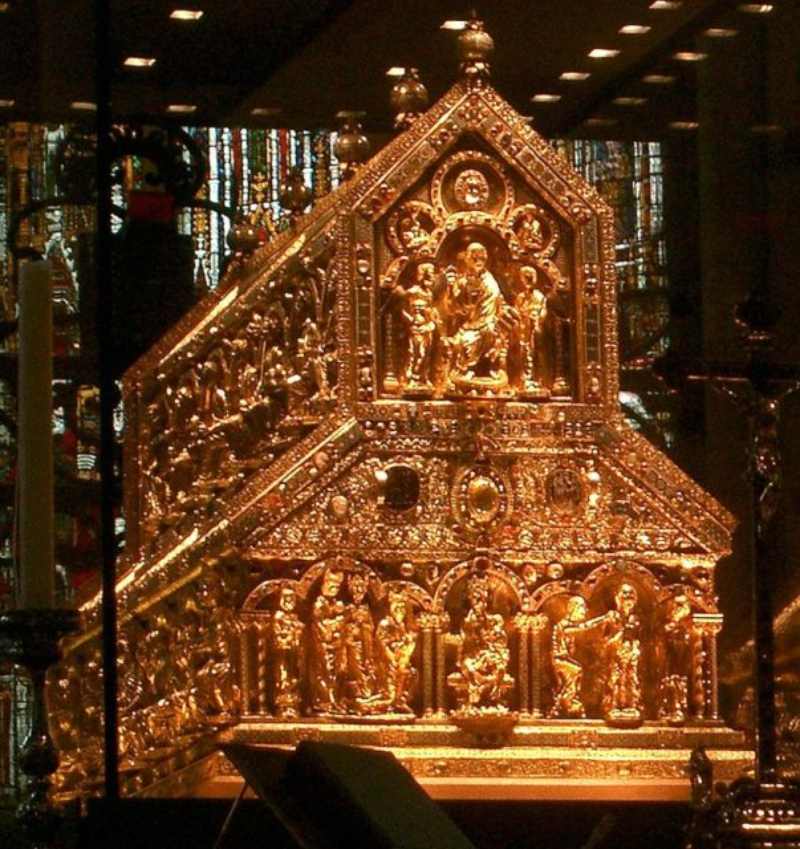

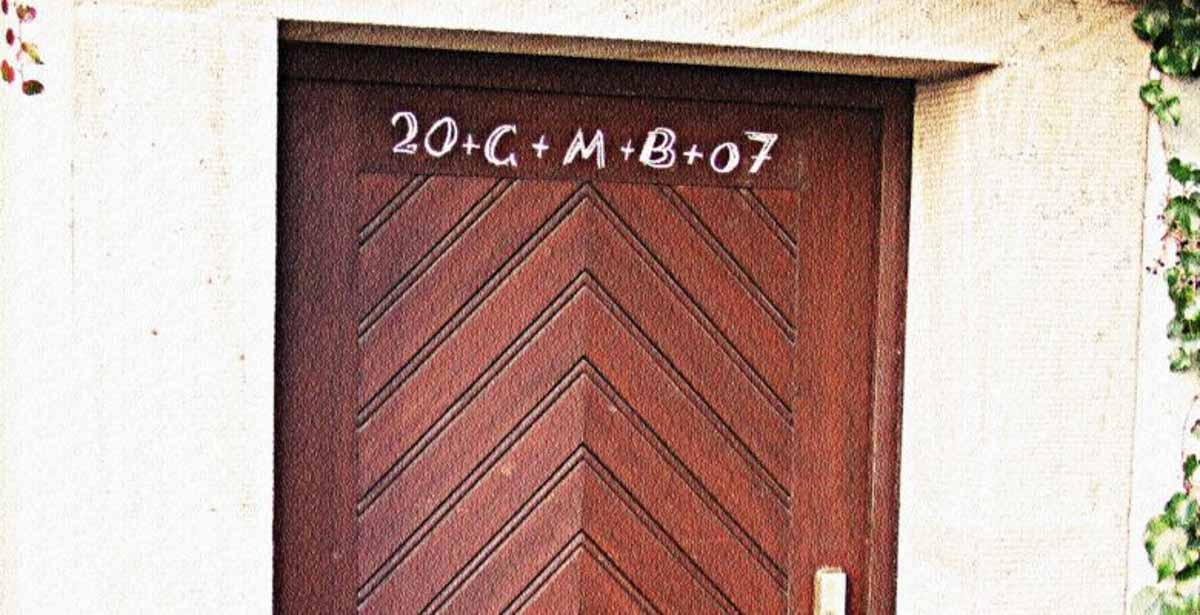

There was also a dramatization of the shepherds’ news of Christ’s birth (the Shepherds’ play) and the three wise men’s devotion to the newborn (the Three Kings’ play). The Magi Play in Freising, Germany, was one of the first Three Kings’ plays that has been preserved textually. It depicted the events leading up to the Nativity of Christ in one hundred Latin lines, including the escape to Egypt. Around the year 1080, Freising Cathedral probably staged its first performance without scenic representation.

From these roots, Nativity plays emerged in the 12th century. From the 13th century, the Nativity Play from Benediktbeuern (Germany) in Latin (Ludus scenicus de nativitate Domini) is preserved as part of the Carmina Burana manuscript, which also contains a Passion play. The Nativity Play differs from the Nativity Play mainly because it includes additional scenes from the Bible, such as the expulsion of Adam and Eve from paradise, a prophetic play, and the events from the Annunciation to the Flight to Egypt. Stube plays, which meant “nativity plays” performed in a living room or guest room without a dedicated stage, were also common in Styria and Carinthia in Austria.

According to tradition, both the Nativity play and the Christ Child cradle of the Dominican nuns, as well as the Christmas crib, trace back to the year 1223. Allegedly, at that time, Francis of Assisi staged the Nativity scene in the forest of Greccio with live animals and people, anticipating the Feast of the Epiphany. Since then, the Franciscans have promoted this form of representation, which persisted even after the Reformation.

Instances of Nativity Play Around the World

The practice is more recent in certain areas; for instance, the Nativity Play has only been put up since 2009 at Sassi di Matera, the oldest section of Matera (Basilicata), which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Approximately 300 people from the Italian town of Genga in the province of Ancona take part in the Presepe di Genga, the biggest Nativity Play on Earth. It takes place every year in the caverns and their surroundings on the slopes of Mount Frasassi. The Slovenian Postojna Cave hosts similarly ornate Nativity Plays underground.

Other European nations, including Germany, France, and Spain, as well as Central European nations like Poland and the Czech Republic, also have Nativity Plays. Stará Plzeň and several other towns and cities in the Czech Republic have Nativity Plays. Countries in Central and South America, as well as a few US states, have adopted this practice. As an example, Nativity Plays have been created by the Baptist Church in Lafayette, Indiana, as well as other places in Texas and Arkansas. On thirteen indoor and outdoor stages in Mount Laurel, New Jersey, nearly two hundred artists play each December for an audience of over thirteen thousand.

In Germany, Austria and Switzerland

- Meyer’s Nativity Play depicts the Christmas tale (a mash-up of the Three Kings, Messenger, Herod, and Shepherd plays) all the way up to the beginning of the worship at the crib. It is a lengthy Latin fragment with instructions from the 12th century.

- Among Austria’s many traditional Nativity Plays, a famous one is performed in Ischl. Although transcription has been around since the 11th century, the first recorded example is from 1654. The Parish Church of “Bad Ischl” still hosts the performance every four years.

- The late Middle Ages were also the birthplace of the Hofer Christmas drama. The cantor and the St. Lorenz parish school choir took care of the music. The St. Michael’s Church Hofer Latin School carried on the tradition even after the Reformation. Ludger Stühlmeyer’s Nativity Play children’s cantata continued the tradition at St. Marien’s City Church.

- Since the 1920s, the Lübeck Katharineum has hosted a Nativity Play in Low German during Advent every year at the Aegidienkirche in Lübeck.

- Waldorf schools are known for their renowned Oberufer Nativity Play.

- At the Christmas market in Andernach, performers bring the Nativity scene to life. On display in the marketplace is a cradle that represents the events surrounding the birth of Christ. The scene unfolds in a pastoral setting, complete with oxen, donkeys, sheep, shepherds, the three wise men, Mary, Joseph, the angel, and the Christ child. On weekends, there are two performances every day.

- Beginning with the 2013 Swiss Huttwil Christmas market, Roland Zoss has been performing the contemporary Chinder Wiehnacht in the Alemannic dialect in several churches.

A Nativity Play Ban in Germany

When the city government of Worms in Germany forbade the Evangelical Lutheran community from performing a Nativity Play in the Christmas market in the lead-up to the 2014 holiday season, the incident garnered national attention. The Mainz Administrative Court upheld this restriction on the grounds that the Nativity performance would interfere with other people’s freedom to freely attend the Christmas market. The congregation’s goal in staging the Nativity Play was to bring focus to the situation of refugees. The municipal administration’s decision to ban the Nativity performance was met with severe criticism from the evangelical deanery, Worms-Wonnegau. According to Dean Harald Storch, panic and escape are fundamental elements of the Christmas narrative.

Nativity Plays in Hungary

A unique variation of the nativity scene is the puppet dance nativity scene. It occurs in the Hungarian language area in the Transdanubia and Upper Tisza regions.

Characters: Angel in a white woolen shirt, with a towerless and open-sided puppet dance nativity scene (see the first picture on the first board); first, second, and third shepherds in turned-out sheepskins with sticks; Old Man – similarly, with a long hemp beard and a cauldron. Names of puppets: bride, deaconess with a bell-shaped alms box, two shepherds, friend, chimney sweep, and devil. In the illuminated nativity scene, there is a crib with baby Jesus, Joseph, Mary, animals, and on the wall, holy images can be seen.

– Hungarian Folklore Collection Volume VIII: Transdanubian Collection: Nativity Plays and Christmas Carols, 2–81