- Indricotherium, an enormous herbivorous mammal, lived in Asia.

- Resembling rhinos, they lacked horns and had long necks.

- Names like Indricotherium, Paraceratherium, and Baluchitherium are often used interchangeably to refer to these animals.

Extinct in the 30–20-million-year-old Middle Oligocene–Early Miocene epochs, Indricotherium (a Latin word from “indrik“—a unicorn-like mythological beast in Russian mythology and from ancient Greek Θηρίον—animal) is a genus of mammals in the family Hyracodontidae. Most indricothere fossils have been unearthed around Asia. Beluchitherium, discovered in the Oligocene of Mongolia, and Aralotherium, discovered in more recent strata in the Aral Sea in Kazakhstan are close relatives of Indricotherium.

Features of Indricotherium

The enormous Oligocene animals known as Indricotherium originated in Asia. It was a relative of modern rhinos but was hornless. Its diet consisted mostly of the foliage of towering trees, since it was an herbivore. Indricotherium fossils have been discovered in Central Asia as well.

How Did Indricotherium Look Like?

They resembled rhinoceroses in many ways, including their body forms, long and straight three-toed legs with a substantially expanded middle toe, and a small head on an unusually long neck. However, they did not have horns and had a domed skull instead of a flat one.

Size and Weight

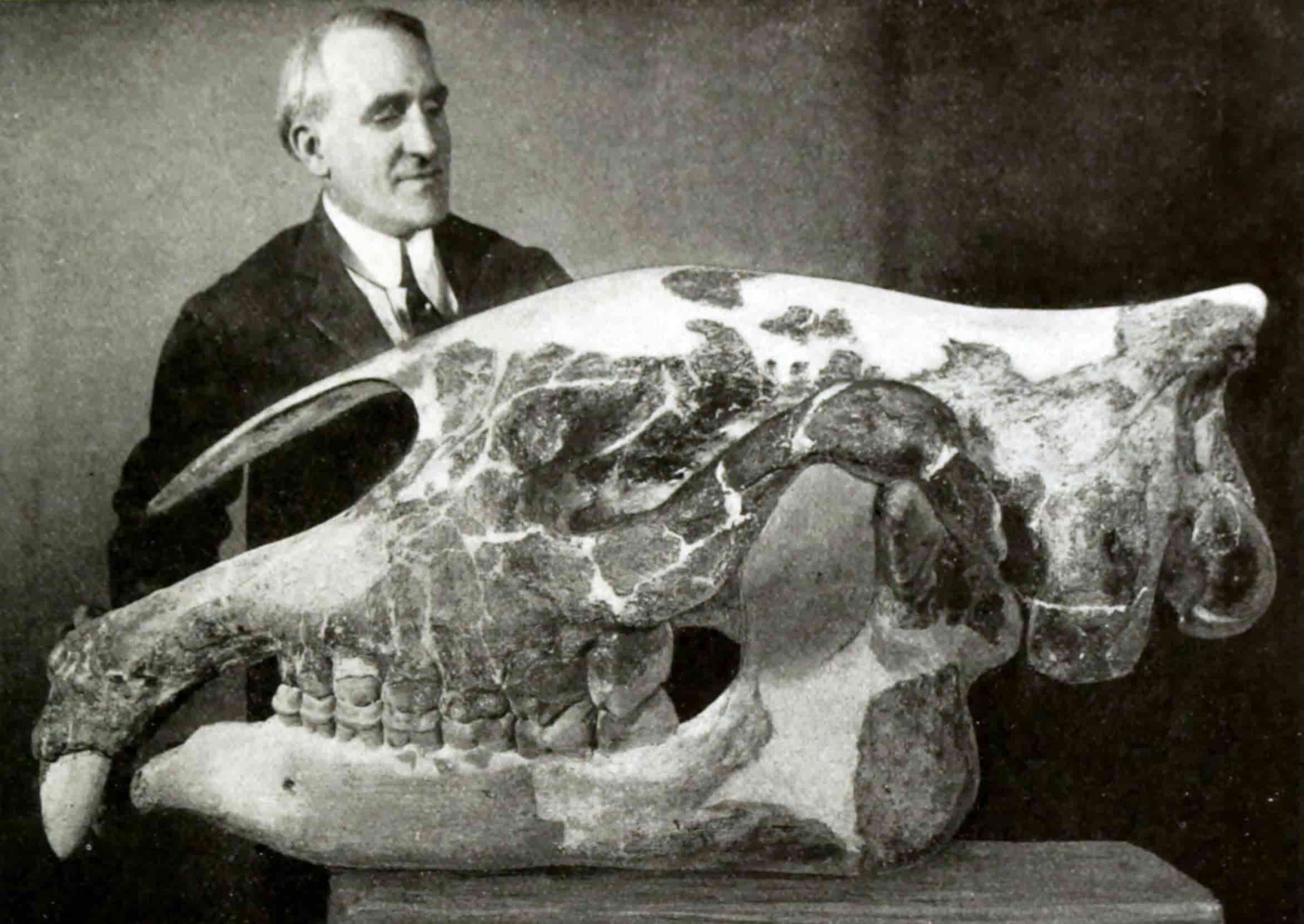

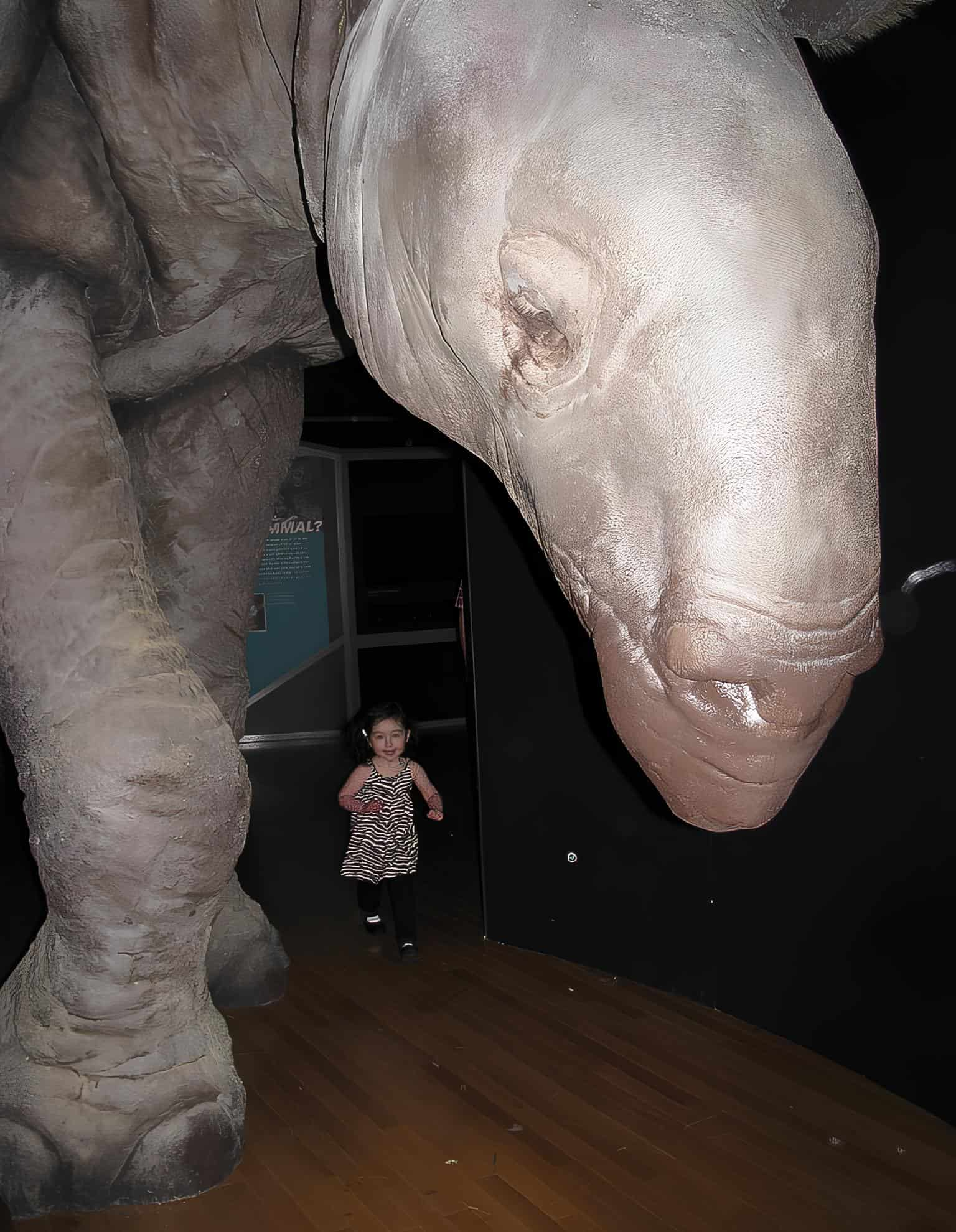

The largest ever mammals were the Indricotherium and Beluchitherium, which could grow to be 18 feet (5.5 m) in height at the shoulder and 28 feet (8.5 m) in length. These animals weighed 20 to 25 tons. The length of Indricotherium’s skull was almost 4.6 feet (1.4 m).

Their Diet and Habitat

The legs were long and huge, much like an elephant’s today. They ate grass and the leaves and branches of bushes and trees. Some of them lived in semiarid or desert environments, while others preferred damper environments like woods or wetlands.

Perhaps the emergence of more specialized big herbivorous animals contributed to the demise of indricotheres (the members of Indricotherium). While giraffes and proboscideans specialized in eating tree branches, short-legged rhinoceroses were better suited to devouring low grassland plants.

Indricotherium, Paraceratherium, and Baluchitherium

Although the species within the genus Indricotherium are well-known, the taxonomy of the genus itself is currently in flux. The first member of the genus Paraceratherium wasn’t named until 1911, when the English paleontologist Clive Forster-Cooper did so. Baluchitherium was another organism he described in 1913. A. A. Borissiak first described the genus Indricotherium in 1915.

Paraceratherium, Baluchitherium, and Indricotherium are all seen as interchangeable terms (Lucas & Sorbus, 1989) and hence equivalent. These names represent different genera within the family Hyracodontidae.

However, there are many who believe the two genera, Indricotherium and Paraceratherium, are distinct. Whatever the case may be, these names all refer to creatures that are around the same size and shape.

Indricotherium transouralicum: Middle to late Oligocene Indricotherium transouralicum (Pavlova, 1922) is the most common and well-studied species among others. Its historical range included what are now parts of Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and northern China.

Paraceratherium orgosensis: The biggest indricothere is Paraceratherium orgosensis (Chiu, 1973). The Xinjiang Uygur area of northwest China is where it was found. Paraceratherium lipidus (Xu and Wang, 1978), Dzungariotherium turfanensis (Chiu, 1973), and Dzungariotherium orgosensis (Chiu, 1973) are all likely to refer to the same species of fossil.

Paraceratherium zhajremensis: The indricothere Paraceratherium zhajremensis (Osborn, 1923) was discovered in the Oligocene of India.

Indricotherium prohorovi: The eastern Kazakh middle and late Miocene are home to the Indricotherium known as Indricotherium prohorovi (Borissiak, 1939).

Paraceratherium bugtiense: The original species of the genus Paraceratherium is found in the middle Miocene of Pakistan and was named by Pilgrim (1908).

Baluchitherium osborni: It is a more recent but etymologically equivalent name (Forster Cooper, 1913) to Paraceratherium bugtiense. It was discovered in Baluchistan’s Chitarwata Formation.

Paraceratherium linxiaense: In the Linxia-Hui Autonomous District of Gansu Province, at the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, Paraceratherium linxiaense (Tao Deng, 2021) was found in late Oligocene sediments (26.57 million years old). At the time of its description, it was estimated to weigh 24 tons and stand 13 feet (4 m) tall (around 27 feet high at the shoulder).

Indricotherium in the Cultural Realm

- Paraceratherium or Indricotherium was the inspiration for the design of the walking battle machines AT-AT used by the Empire in the “Star Wars” film series.

- V. A. Obruchev mentions indricothere in his book Plutonia.

- The third episode of the British documentary series “Walking with Beasts” is devoted to the indricothere’s early years.