The fossils of the extinct Oxyaenodonta mammal Patriofelis (genus Patriofelis) have been discovered in North America, and they existed during the middle Eocene (about 48 to 40 million years ago). Although the resemblances between this predator and a modern jaguar were the consequence of convergent evolution, they were still strikingly similar. Patriofelis was a massive Oxyaenodonta (“sharp hyena”), measuring in at over 100 inches (250 cm) in length (including its tail).

The Discovery of Patriofelis

Joseph Leidy initially defined the genus Patriofelis in 1870 using fossils discovered in Middle Eocene soils in Wyoming; the type species is Patriofelis ulta, which was also discovered in Colorado. Fossils of P. ferox, another well-known species, have been discovered in somewhat older soils in Wyoming and Oregon.

Patriofelis is typical of the Oxyaenodontas (“sharp tooth hyenas”), a widespread group of animals from the Paleocene and Eocene that exhibited extreme carnivory. Among the Oxyaenodonta, Patriofelis was both huge and highly specialized. The smaller Oxyaena, the related Malfelis genus, and the enormous Sarkastodon were its closest relatives.

The Lifestyle of This Animal

A Scavenger

Despite its small size, Patriofelis was clearly an effective predator because of its robust set of teeth and smaller skull. Patriofelis must have been an active scavenger, since the skeleton seems to be designed to enable the animal to climb trees, despite this trait being more often associated with predators who feed on carrion. Not built for speed, this predator was better adapted to ambush hunting.

Unique Adaptations

Since the fossils of Patriofelis have been discovered at river deoposites and flood zones, this may imply that this animal was suited to walking on soft terrain, like riverbanks. Because of its small legs and widely spaced fingers, several researchers have hypothesized that Patriofelis was a strong swimmer. Given Patriofelis’ massive size, it’s hard to believe that this animal ever engaged in burrowing behavior, as suggested by the morphology of its upper arm bone (humerus) and hand.

The Distinct Features of Patriofelis

Powerful Jaw Muscles and a Strong Bite

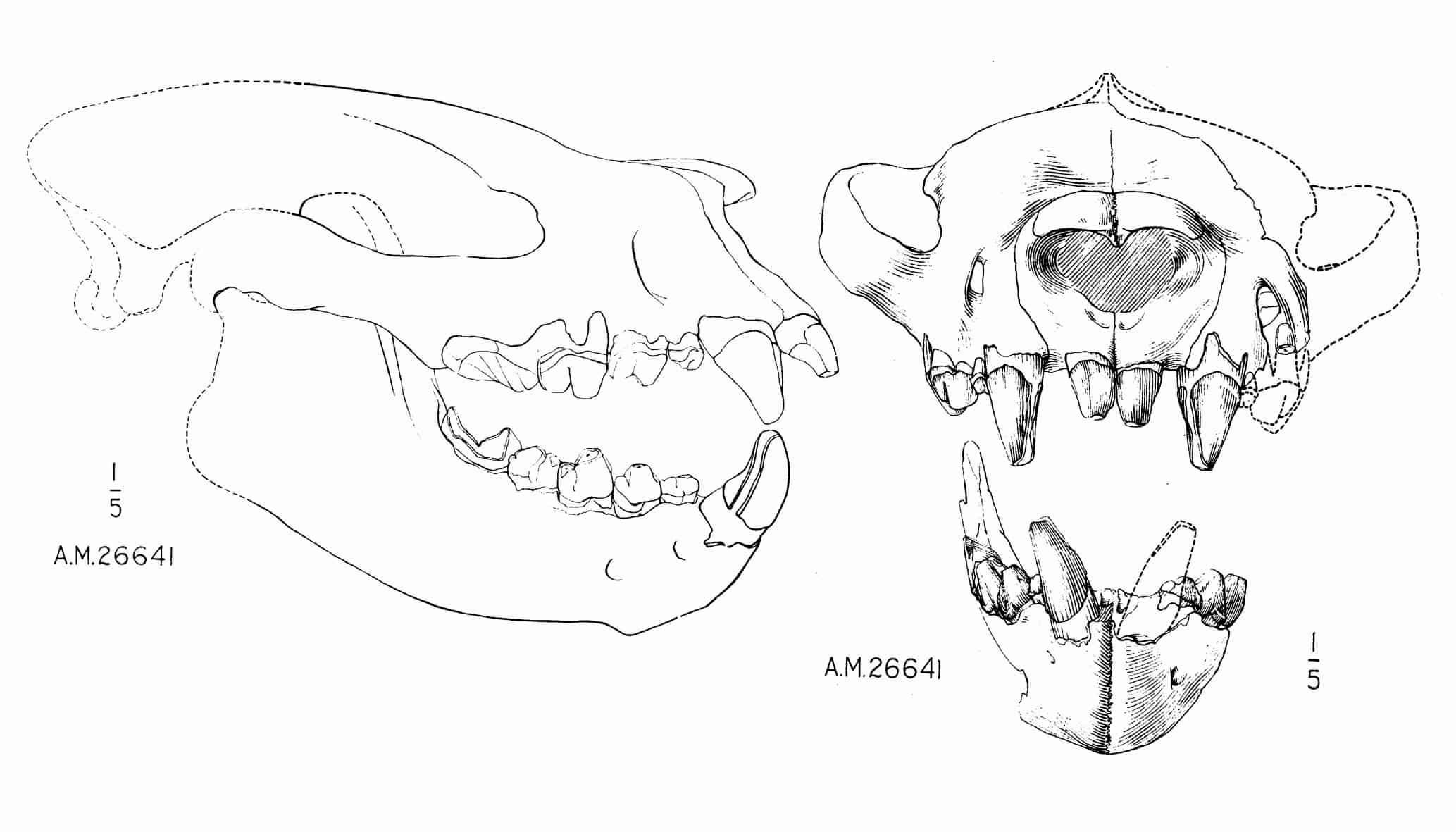

The cranium of this prehistoric animal was huge, measuring up to 10 inches (25 cm) in length and as big as a lion’s. It also had a short nose. In contrast to other creodonts (“meat teeth”), Patriofelis had some distinct skull features. For starters, it had special ear bones (ossified tympanic bulla) and passages in its skull that were likely linked to its hearing, sensory perception, facial expressions, etc.

When we look at its skull, we see large ridges where muscles are attached, showing it had powerful jaw muscles. Its cheekbones were strong, and its lower jaw was sturdy despite being not very long. Interestingly, the teeth of this ancient animal were quite distinct. The upper premolars had sharp internal edges, and their incisors were smaller than their canines. It was also missing its top third molar. Additionally, the upper back teeth were shaped like sharp blades, indicating they likely had a strong bite.

All these features give us clues about Patriofelis as a prehistoric mammal. It probably had a strong bite and might have been really good at hunting. Thanks to its ear bones and facial structures, it had acute senses like a modern felidae.

A Shorter Body but a Muscular Tail

Patriofelis had a somewhat sturdy skeleton. It had a shorter body and a neck of average length compared to other creodonts. The lumbar vertebrae in Patriofelis connected in a way that resembled how some animals with split hooves, like deer or cows, have their spines arranged.

However, it was on a more complicated scale. A long, muscular tail curled out from the body towards the end.

The lower extremities, and the forelegs of the Patriofelis in particular, were short and powerful. The shoulder blade of Patriofelis had specific features. It had two equal-sized depressions and large protrusions. Additionally, there was a visible bony projection. These shoulder blade characteristics indicate good mobility and advanced hunting techniques for Patriofelis. These features were generally typical among early meat-eating animals.

Patriofelis shared similarities in its upper arm bone with its relative, the Oxyaena (“sharp hyena”), but it had more distinctive traits. Notably, it had a highly developed deltoid crest, which is a bony ridge where powerful shoulder muscles attach. Thus, Patriofelis likely had strong chest and shoulder muscles which makes it powerful as a predator.

Powerful Leg Muscles

As expected, the size of the olecranon (an elbow bone), along with other features, suggests that Patriofelis was exceptionally adept at walking. Its well-adapted limbs and muscles likely allowed it to move efficiently.

Patriofelis also had a unique hip and leg structure. Its femur, the thigh bone, could move freely due to its long ilium (a part of the pelvic bone) which provided a sturdy base for attaching powerful gluteal muscles that are crucial for movement. A bony protrusion on the femur was positioned at a higher angle in Patriofelis which indicates robust leg muscles.

Almost Dull Claws

The limbs of this animal ended in pentadactyl hands and feet, meaning it had five digits on each. This is still a common trait among mammals after millions of years. However, Patriofelis had small and widely spaced toes with slightly blunt nail phalanges, suggesting that its claws weren’t extremely sharp.

These features hint at its ability to walk effectively but it might not have been specialized for climbing or grasping prey with its claws because its claws probably weren’t that sharp.