The Yule Lads, or the Jólasveinarnir in Icelandic, are legendary figures that are said to reside in the mountains and make an appearance in the town 13 nights before Yule. They are all named after things that describe how they like to cause trouble. They put presents in the shoes that kids have left on the windows, but if the kid has been bad, they put a spoiled potato in there instead.

Iceland passed a law outlawing the transmission of terrifying tales about the Yule Lads to youngsters in 1746.

Therefore, these characters have evolved into more sympathetic characters throughout the years and become the children of the witch Grýla and his husband Leppalúði, two other mischief figures.

Family of the Yule Lads

The Yule Lads were originally monsters who ate disobedient children and naughty animals that left presents at night. In recent times, they have taken on greater charitable responsibilities. The 13 Yule Lads are shown as living inside a cave together as a family:

- Grýla is a giant who eats mischievous children cooked in a cauldron.

- Leppalúði is her husband who is sluggish and spends most of his time in the cave.

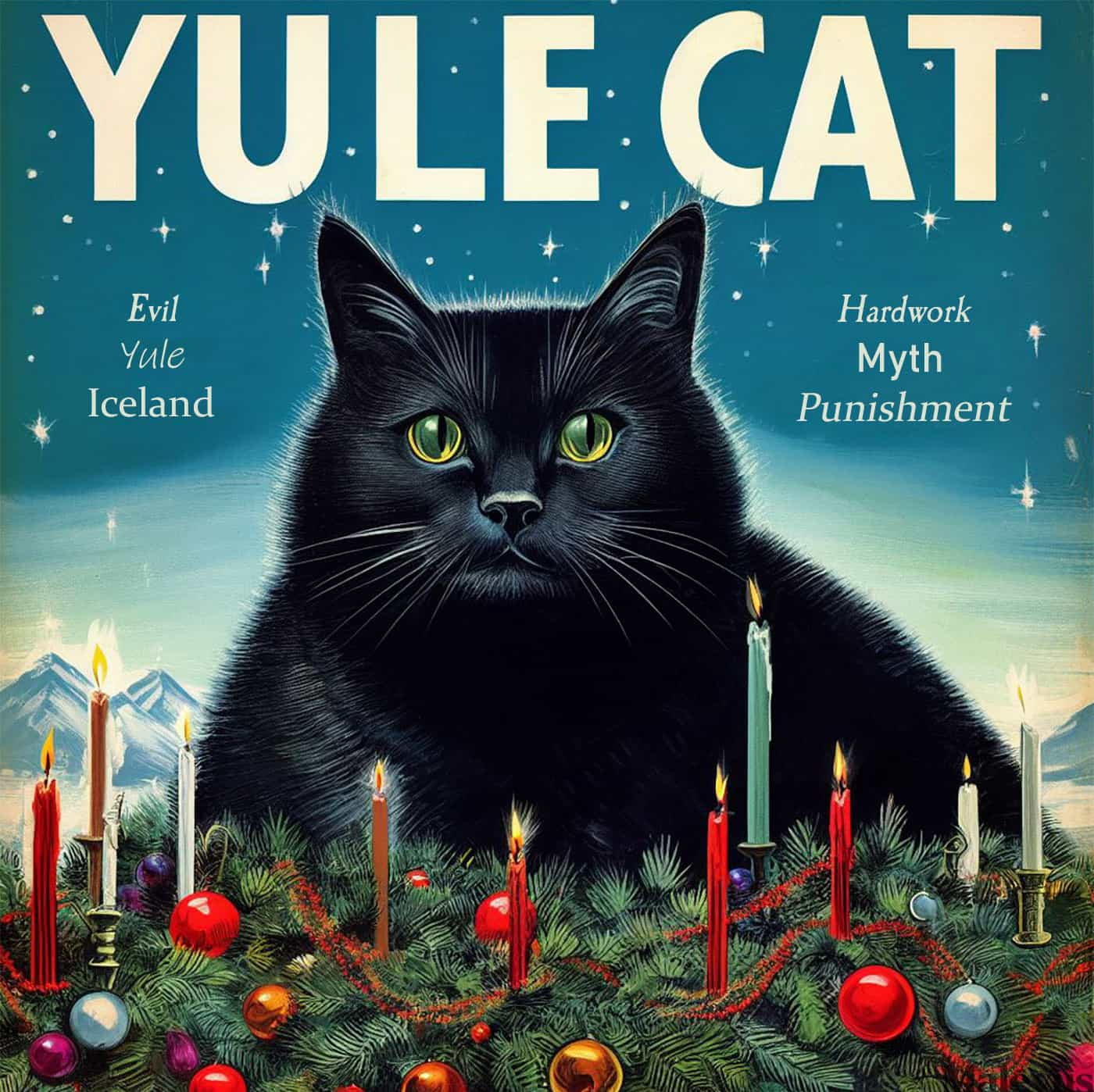

- Yule Cat or Jólakötturinn is a gigantic and evil cat that lurks in homes during Yule and eats anyone who hasn’t gotten clothes as a gift before Yule.

- The Yule Lads are the offspring of Grýla and Leppalúði. They are a group of trolls causing mischief to the population during Yule. In the thirteen nights leading up to Yule, they make their way to town one by one each day to either deliver gifts or punishment for the children.

Originating in the 17th century, the specifics of these Yule tales changed with the times and places they were told. Their tales are now meant to inspire good conduct. Translations of the poem by Hallberg Hallmundsson served as a source for the English names of Yule Lads.

List of Yule Lads

The Yule Lads come into town on December 12 and depart in the same order (beginning on December 25); hence, each boy stays for thirteen days. This happens on each of the thirteen nights leading up to Yule Day. The thirteen Yule Lads are listed below according to the sequence in which they come and go.

| Yule Lads | Meaning | What He Does | Arrives | Leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stekkjarstaur | Sheep-Cote Clod | Causes trouble for sheep but faces hindrance due to his wooden legs. | 12 December | 25 December |

| Giljagaur | Gully Gawk | Lurks in gullies, patiently awaiting a chance to slip into the cowshed and steal milk. | 13 December | 26 December |

| Stúfur | Stubby | Unusually small in stature. Steals pans to consume the remnants of crust left on them. | 14 December | 27 December |

| Þvörusleikir | Spoon-Licker | Snatches and licks wooden spoons. Extremely thin as a consequence of malnutrition. | 15 December | 28 December |

| Pottaskefill | Pot-Scraper | Steals remnants from cooking pots. | 16 December | 29 December |

| Askasleikir | Bowl-Licker | Lurks beneath beds, anticipating the moment someone sets down their askur (a bowl with a lid), which he proceeds to steal. | 17 December | 30 December |

| Hurðaskellir | Door-Slammer | Enjoys shutting doors during the night to wake people up. | 18 December | 31 December |

| Skyrgámur | Skyr-Gobbler | Enjoys skyr (similar to yogurt) a lot. | 19 December | 1 January |

| Bjúgnakrækir | Sausage-Swiper | Conceals itself in the rafters and grabs smoked sausages. | 20 December | 2 January |

| Gluggagægir | Window-Peeper | An intruder who peeks through windows, searching for items to steal. | 21 December | 3 January |

| Gáttaþefur | Doorway-Sniffer | Possesses a large nose and a keen sense of smell just to locate leaf bread (laufabrauð). | 22 December | 4 January |

| Ketkrókur | Meat-Hook | Utilizes a hook to pilfer meat. | 23 December | 5 January |

| Kertasníkir | Candle-Stealer | Chases after children to take their candles, which were once made of tallow and thus edible. | 24 December | 6 January |

Origin of Yule Lads

The 17th-century Poem of Grýla was the initial reference to the Yule Lads. Grýla, previously a troll in tales, had no prior association with Yule.

She serves as the fearsome mother of the Yule Lads, posing a threat to children. Initially, various types of Yule Lads existed, with descriptions ranging from harmless pranksters to child-devouring monsters, depending on the region. Similar to the boogeyman, they aimed to encourage good behavior.

However, in 1746, King Christian VI of Denmark (1699–1746) opposed the use of these tales as a form of punishment. This apparently small decision in the last year of his life changed the course of the history of a national folklore story. In the late 18th century, a poem featuring thirteen Yule Lads emerged. Inspired by the Brothers Grimm, Icelandic folklorist Jón Árnason began collecting tales in the 19th century, introducing the Yule Lads in his 1862 anthology. Icelandic poet Jóhannes úr Kötlum included the Yule Lads poem in his widely-known 1932 collection, “Jólin Koma” (Yule is Coming) which has cemented the identities, names, and the thirteen canonical Yule Lads.