Aerial Screw: Leonardo da Vinci’s Helicopter

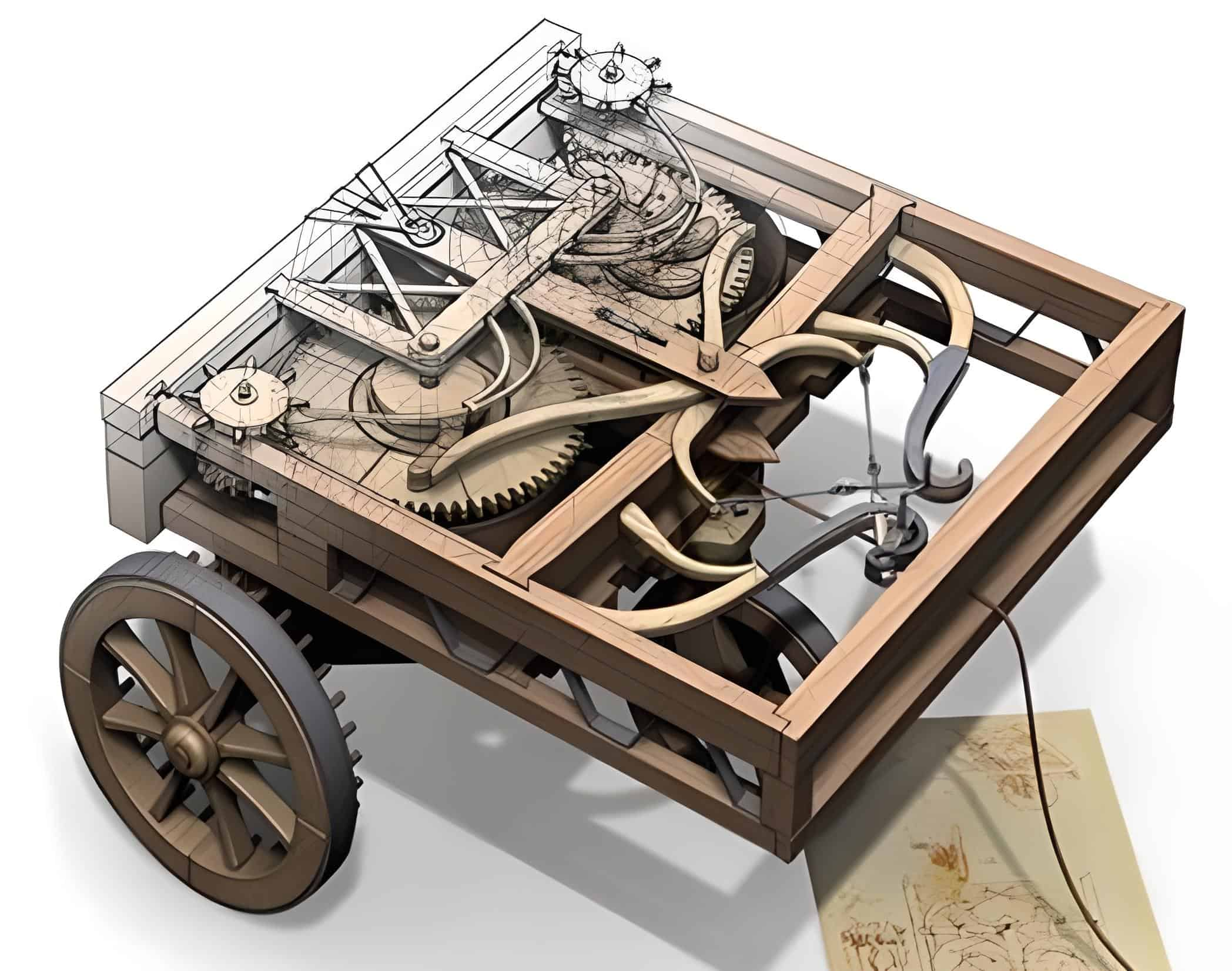

While working as a military engineer for the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo da Vinci considered the possibility of the first human flight after his studies on perpetual motion, his spring-powered cart of 1478, and his tank of 1485.