In June 1928, American Amelia Earhart made history by being the first female pilot to fly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. In 1937, she attempted to become the first woman to fly around the globe, but she vanished under strange circumstances. Though over 95 years have passed, many unanswered questions surround the disappearance of the American aviatrix. Doubts persist despite the many studies done to learn what became of the adventurer destined for greatness. Just a few short decades were all it took for this trailblazer to leave an indelible imprint on aviation.

Who was Amelia Earhart?

Amelia “Amelia” Earhart was born on July 24, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas. Even as a little girl, “Meeley” (as she was called) exhibited a penchant for exploration and outdoor play with her younger sister. Amelia wasn’t interested in flying until years after she found out what an aircraft was for the first time at age 10.

The young lady joined her sister in Toronto, Canada, after finishing high school in Chicago and college in Pennsylvania. There, they were exposed to the horrors of World War I. In 1917, after seeing the homecoming of injured troops, she became a nurse’s assistant for the Canadian Red Cross. While volunteering at a military hospital the next year, she contracted the Spanish flu while working with its patients. After this, she decided to enroll in medical school, but she dropped out after only a year.

How did Amelia Earhart become an aviator?

A 23-year-old American’s life changed forever in 1920 when her father escorted her to a Long Beach airport to see a pilot. Neta, aka Mary Anita Snook, was an early female pilot in the United States, beginning her career in 1917. Amelia took flying lessons from her for $1 per minute.

For that lesson, Amelia’s income came from two side jobs, but the one that paid the most was driving an old truck full of gravel for a construction firm. She hadn’t yet flown solo when she realized she wouldn’t be a “genuine” pilot until she had her own aircraft.

After just 10 minutes in the air, she knew she had to become a pilot. She worked several jobs until she saved enough money to begin flying training. She saved up enough money in the summer of 1921 to purchase a brilliant yellow biplane she dubbed “The Canary.”

In 1922, she took to the skies in her aircraft and went as high as 14,100 feet (4,300 m). A female pilot has never before accomplished this before. Amelia Earhart was the sixteenth American woman to get a pilot’s license in May of 1923. In 1925, she moved to Massachusetts to begin a career in social work, but her love of flying never left her.

First woman to fly across the Atlantic

Historically, aviator Charles Lindbergh made headlines in 1927 when he flew alone from Paris to New York. The notion of accomplishing the same feat with a female pilot took shape. There were five people who set out to do the adventure, but none of them made it. Until April 1928, when Amelia was approached to give it a try. She departed Newfoundland on June 17 in a three-engine aircraft flown by Wilmer Stultz and staffed by Louis Gordon, a mechanic.

20 and 40 minutes later, the gang arrived in Welsh territory. Amelia Earhart was greeted with a hero’s welcome when she made history by being the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. Her description of the voyage, published in Times on June 19, 1928, emphasized that during the flight she was only a passenger.

However, Amelia Earhart was now a renowned aviatrix. The moniker “Lady Lindy” was given to her because of her likeness to Charles Lindbergh. Some months later, she proved her abilities by completing her first solo transcontinental journey. She reached a height of 18,415 feet (5,613 m) and a speed of 180 miles (291 kilometers) per hour in 1930, both world records for a female pilot.

She married her publisher, George Putnam, in 1931, without giving up her independence or her flying interests. The level of attention given to Amelia Earhart increased dramatically. Both the Distinguished Flying Cross and the National Geographic Society’s Gold Medal were awarded to her in 1932, making her the first woman to earn either honor. She didn’t rest on her laurels, however; rather, she continued to push herself and her achievements to new heights. As an example, she made the first solo flight from Los Angeles to Mexico City (1935).

On May 20, 1932, at the age of 34, she flew across the Atlantic Ocean alone once more, this time in a Lockheed Vega. Her flight from Harbour Grace, Canada, to Derry, Northern Ireland, lasted 14 hours and 56 minutes. The achievement was again well covered by the press of the day, despite the leak that caused her to return to ground sooner than expected.

Le Populaire ran the title, “Five years after Lindbergh, the young American Miss Amelia Earhart, alone on board her plane, managed to cross the Atlantic from Newfoundland to Ireland” on its front page on May 22, 1932, over a portrait of the aviatrix with a broad grin. Amelia Earhart conducted many further solo flights, including a historic crossing of the Pacific Ocean from Hawaii to California, before 1935.

Amelia Earhart’s last flight

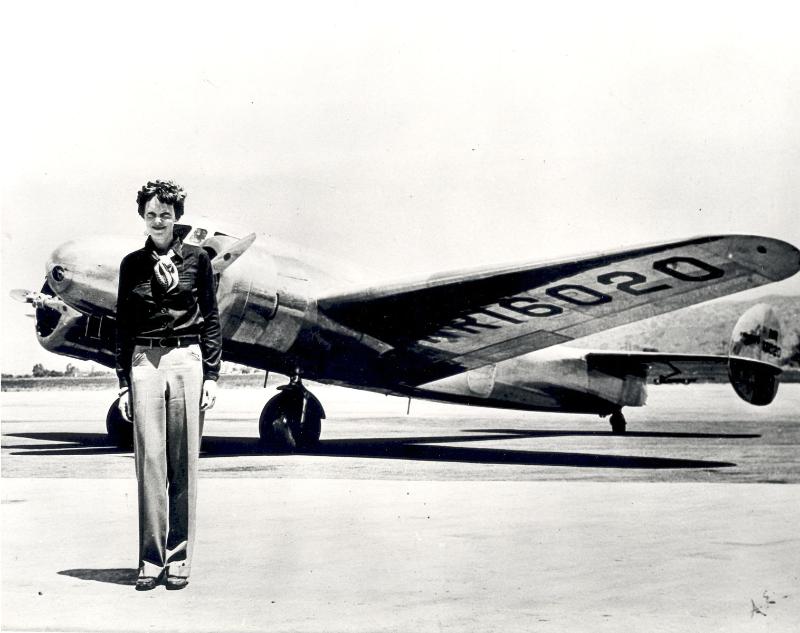

Amelia Earhart first considered doing a circumnavigational flight in 1936. After purchasing a Lockheed L-10 Electra, she dubbed it her “flying laboratory.” The first attempt to take off was in March of 1937, and after that, it was June before another flight was made. This time, Amelia Earhart made it from Miami to Lae, New Guinea, with pilot Fred Noonan, traveling a total of nearly 21,700 miles (35,000 km) through a number of intermediate cities.

They still needed to go somewhere about 6,835 miles (11,000 km) away before their journey was completed. On the afternoon of July 2, 1937, the two set off from a Lae airfield in search of Howland Island, located in the middle of the western Pacific, where they planned to refuel. Both pilots were lost in transit and never made it to their destination.

Her biggest challenge was undertaking the first female round-the-world flight, which she attempted in 1937. The day she disappeared, July 2, 1937, she transmitted an ominous communication to a ship near the Pacific island of Howland. Although President Roosevelt took involved in the search, it was ultimately determined that she had passed away in 1939.

Amelia Earhart’s mysterious disappearance

The rapid notification was sent on July 2, after Earhart and Noonan had shown no signs of life for many days. We studied the pair’s last exchange of text messages. They could only fly for 30 minutes and said that they could not see the island due to a lack of fuel. In an effort to locate the pilots and their aircraft, search parties were sent immediately. Attempts that bore no fruit. On July 3rd, with no tangible clue in sight, optimism was at an all-time low. Unfortunately, the investigation into the fate of the crew members was halted in the middle of July 1937.

Most experts agree that the jet lost its way after deviating from its intended course. Having depleted its fuel supply, it would have plummeted toward the ocean, eventually sinking under the waves and taking its passengers with it. There have been several, more or less credible explanations for this disappearance. Speculations range from the plane being shot down to Earhart being taken prisoner by the Japanese.

Nikumaroro Atoll, previously known as Gardner Island, has been proposed as an alternative crash site for pilots. Amelia’s husband, George Putnam, funded studies until October 1937, but they found no evidence to support any of the claims. In January of 1939, it was officially announced that the aviatrix had passed away.

Bones found in Nikumaroro

The terrible disappearance of the aviation pioneer has not been solved despite the passage of more than 90 years. Evidence has accumulated in favor of one of the ideas, the Nikumaroro atoll theory. In 1940, the island was the site of an expedition that uncovered human remains and other artifacts, such as a sextant. Although the bones were examined as early as 1941, their whereabouts since then are unknown, prohibiting any further testing, notably DNA testing, that may reveal the name of their owner.

An updated examination of the measurements collected at the time of discovery was published in 2018 by University of Tennessee anthropology professor Richard Jantz, who claimed that they were “more comparable” to the missing aviatrix than to “99% of the persons in a large reference group.” Though this was a significant breakthrough, it was not enough to solve the mystery for good.

The atoll was the site of several excursions after 1940, with more potential camp remnants, including shoe fragments and a pocket knife, being uncovered. Once again, though, the collection fell short of providing enough evidence to positively identify the owner.

In 2019, Robert Ballard, the American wreck hunter famed for discovering the Titanic’s ruin, led an expedition off the deserted coast of Nikumaroro in search of Amelia Earhart. Unfortunately, no aircraft or debris was located after extensive searches over the course of many days.

A pioneer who continues to inspire

It is hard to determine whether or not the fate of Amelia Earhart, who may remain one of aviation’s biggest mysteries, will ever be solved. But it hasn’t stopped “Miss Lindy” from becoming a legend and an inspiration that intrigues people even now, more than 90 years after her death.

Many people have paid their respects to her memory since her passing. Amy Adams, who played her in the sequel to Night at the Museum (2006) is only one of the many actors who reference her or play her in dramatic works.