Jerusalem has been around since ancient times, and it has been a holy city for Jews, Christians, and Muslims ever since. Ancient Jerusalem flourished around 2000 BC, rising rapidly to prominence as one of the principal Canaanite era city-states before falling under Egyptian control. In the 10th century BC, after being conquered by King David, ancient Jerusalem rose to prominence as the seat of the Israelite government and the site of the magnificent Solomon’s Temple. Ancient Jerusalem fell under Roman control in the 1st century after being destroyed multiple times.

The Origins of Ancient Jerusalem

It is believed that the first settlers arrived in the area around ancient Jerusalem at the close of the 4th millennium BC. However, the first fortification at the location was built in the 1700s BC, long before the rise of the Israelite kingdom. And Jerusalem was a regional political center long before that.

The name of the “Jerusalem” city is attested in ancient Egyptian records, specifically in the inscriptions unearthed at the site of Tell el-Amarna. This shows the political importance of the city. The major urban growth of Jerusalem, however, did not occur until the 8th century BC.

The city has served as the center of a state for close to two centuries, established by people who name themselves “Hebrews” or “Israelites.” This group claimed Mesopotamian ancestry, but the reality is more likely that its members migrated to Canaan from neighboring regions like Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The governmental presence of ancient Jerusalem is at least as old as the Merneptah Stele, a.k.a. “Israel Stele”, discovered in Egypt which dates back to 1208 BC. The stele is the first written mention of Israel in history.

In the 10th century BC, Israel was divided into two kingdoms: The northern portion of Israel was called the Kingdom of Israel (1047–720 BC), while the southern area was called the Kingdom of Judah (930–587 BC).

Ancient Jerusalem and the First Temple (10th century–587 BC)

There is evidence of ancient Jerusalem’s prosperity in the form of temples, the growth of the city and the wealth of its ancestors, and the construction of important and complex hydraulic infrastructures like the 1,640-foot (500-meter) long Siloam Tunnel (built between 727 and 698 BC). This water tunnel was dug in the rock and connected the spring of Gihon to a reservoir in the City of David.

The devotional impact of building a temple to Yahweh (“God”) on Mount Sinai was the likely cause of Jerusalem’s prosperity. Solomon’s Temple, or the First Temple, is thought to have existed between the 10th and 6th centuries BC. The temple is described in the Book of Kings as a small one, with an entryway dubbed the “Holy of Holies,” where the Ark of the Covenant and the texts from Mount Sinai were kept.

However, no physical evidence of the First Temple (Solomon’s Temple) has ever been found. On the Yom Kippur holiday, only the high priest was allowed inside the temple. At the time, the temple was not used for a monotheistic religion but for a monolatry one (the belief in more than one god).

This evidence is based on the belief in ritual sacrifice, just like in every other Middle Eastern faith. In an essentially polytheistic world, this monolatry inevitably led to monotheism.

Byblos, a place where papyrus was produced, is where the Bible got its name. The same city gave rise to the Greek word biblio, or “book”. This ancient capital of the Levant is believed to have been first occupied between 8800 and 7000 BC.

The Torah, the first five volumes of the Bible, contains God-given laws for general rules of daily life. This is a crucial aspect because it represents one of the most significant traditions that Islam would later adopt. Despite some anomalies, such as the Temple of Elephantine in Egypt (Aswan), the purpose of the Jerusalem temple is reflected in the will to concentrate the worship in Jerusalem.

In 586 BC, Nebuchadnezzar II’s forces stormed Jerusalem and demolished the First Temple. A portion of the city’s populace was taken as captives to Babylon (modern Iraq) after only a part of the city was destroyed. The most influential Israelite society outside of Judea had now been established in Babylon.

Ancient Jerusalem and the Second Temple (516 BC–70 AD)

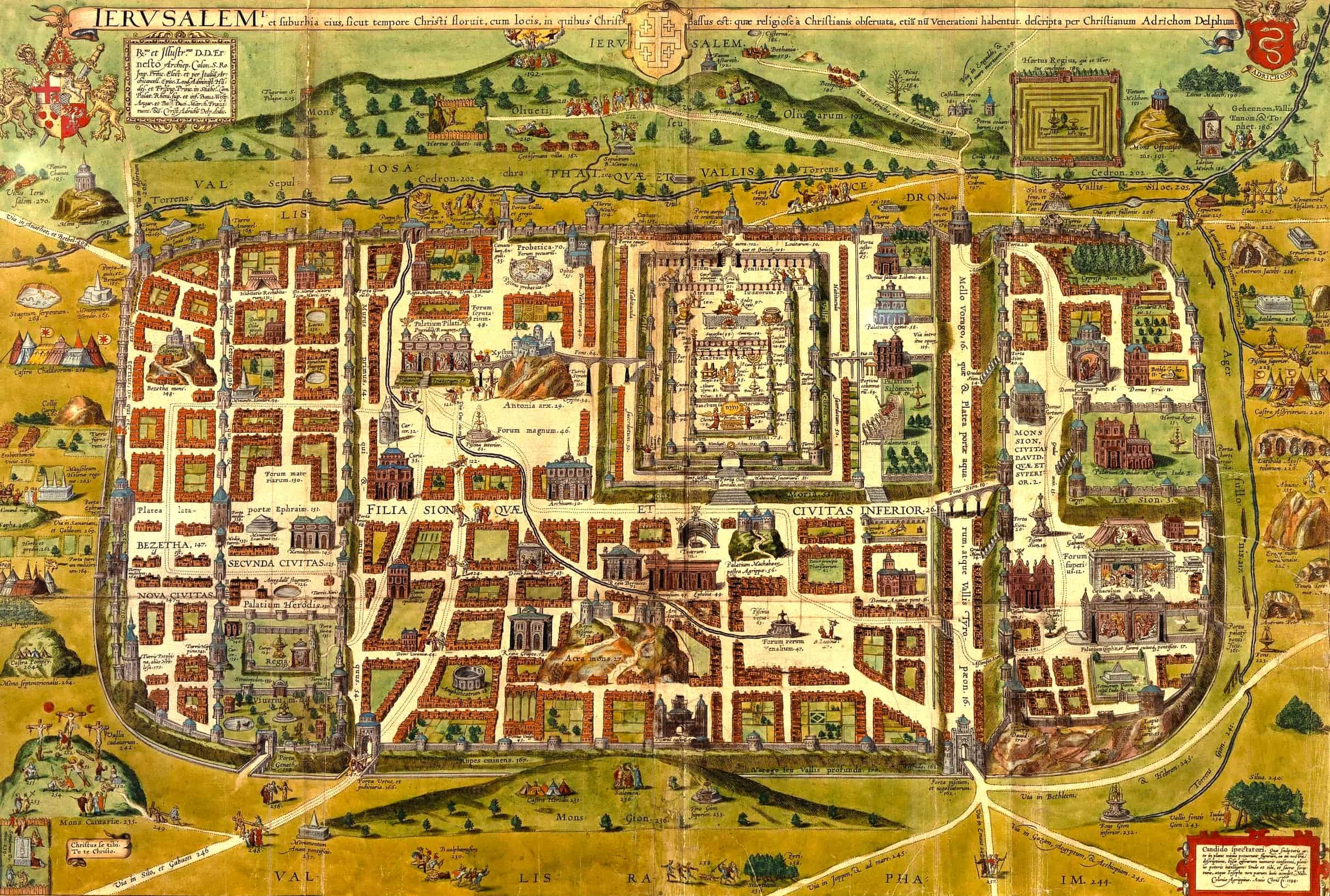

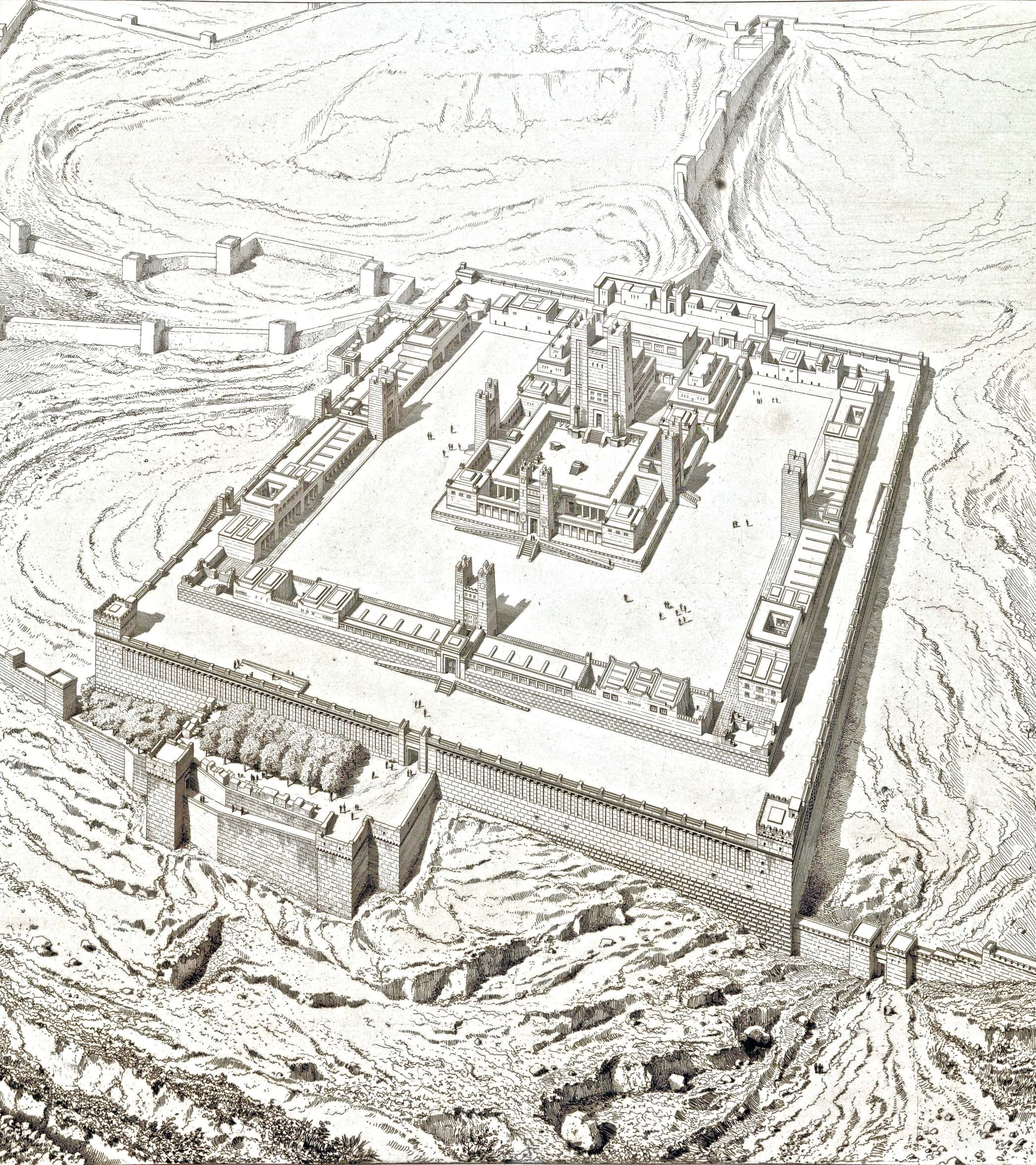

In the northern section of the Temple Mount complex stood the Antonia Fortress, called after a prominent Roman commander. The regal cauldron, a gathering place, courtroom, and center of government, was built in the building’s southern section. In the middle of the mountain rose an inner complex where the sanctuary was situated, and an enclosed tunnel 49 feet (15 m) wide was exposed to the interior of the compound and encircled it from all directions.

With the foundation of a new empire by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC called the Persian Empire, the Near East saw a shift in power. The dominance of this kingdom over the Levant grew. Jerusalem’s citizens received permission from Cyrus the Great to spend years rebuilding the city’s sacred significance by constructing a new temple in 538 BC.

The Second Temple in Jerusalem was built under the watchful eye of foreign forces during the Achaemenid dynasty (Persian culture) and the Seleucid dynasty (Hellenic culture) that followed Alexander the Great‘s invasion. The Greek king Antiochus IV introduced the worship of Olympian Zeus into the Temple of Yahweh (House of Yahweh) in 167 BC, a particularly cruel measure of Hellenization.

This imposition set off what would become known as the “Maccabean Revolt” and lasted until 141 BC. In 164 BC, the worship of Yahweh was reinstated in the Second Temple, and to celebrate this event, the Hanukkah holiday was established.

As a result of this uprising, an autonomous state with Jerusalem as its center and Yahweh as its sole god was restored in the year 141 BC. There was a ruling family, the Hasmoneans, who came to control ancient Jerusalem following the uprising. Even though the Hasmoneans were a sacred monarchy in which the High Priest held absolute authority, they nonetheless Hellenized Jerusalem over time and built tombs in the Hellenistic style.

From roughly 40 BC to 4 BC, the Roman Jewish King Herod of Judea initiated massive construction projects in Jerusalem, most famously on the Temple Mount. To distinguish the Second Temple from the rest of the city, he planned to flatten the temple hill and turn it into an esplanade. The Second Temple grounds were off-limits to non-Jews (Gentiles), and only Yahweh’s cultural adherents were allowed. The Gentiles were restricted to the Gentile Prayer.

Herod’s 19 BC Second Temple (later “Herod’s Temple”) project was not completed until 63 AD. Jerusalem’s connection with the Roman government did not improve after Pompey desecrated Herod’s Temple in 64 BC. The Romans, who viewed religion more as a public good, were taken aback by Judaism’s emphasis on discrimination.

As a Roman influence on ancient Jerusalem grew, so did the Roman offerings performed at the Second Temple. The temple was now a stronghold of the imperial religion.

The Hasmonean dynasty collapsed in 44 BC when Rome chose to establish direct governance in ancient Jerusalem. Because the desecrations were not resolved by this direct governance, the Judeans rose up in 66 AD and were brutally put down by the Roman troops.

After the insurgents sought shelter in the Second Temple during the Roman blockade of Jerusalem in the year 70, the city was plundered and the temple was burned to the ground at the end of that year’s summer. This was four years after the revolt and possibly the day on which Tisha B’Av was observed. The Roman legions under Titus retook and destroyed much of Jerusalem and the Second Temple.

Ancient Jerusalem in Roman Times

The destruction of the Second Temple took time to become accepted. It was a gradual farewell to the Temple in Jerusalem, with no hope of reconstruction, unlike the First Temple.

With the loss of the Temple and the High Priest, the religion became non-sacrificial and was led by the experts in the law: the rabbis. This led to a religion of the Book, and the Judeans gathered in what was called in Greek the “synagogue,” meaning “assembly.” However, the Jews remained haunted by the loss of Jerusalem and the Temple.

The Romans took exclusionary measures against the Jews after a final rebellion broke out in 132, led by Simon bar Kokhba and his men, which lasted until 135. This rebellion was crushed by the Roman legions, but to permanently remove the risk of rebellion, the Romans took drastic measures: circumcision, Sabbath observance, and Torah study were banned in Judea, and the Judeans were banned from entering Jerusalem except once a year. It was the only city in the Roman Empire that became forbidden to Jews.

During that time of year, the Jews would begin visiting the Wailing Wall (or Western Wall) to express their grief over the destruction of the temple and the city of Jerusalem. This permission became a ritual known today as the Western Wall, where Jews still go to mourn the loss of the temple and the city.

This wall was located southeast of Herod’s Temple. Since 135, with Emperor Hadrian, Israel no longer existed as an independent kingdom, and the word by which the Judeans called themselves (yehudim, which originally meant “Judeans”) became an ethnonym for a people in exile. From then on, Yehudim was no longer translated as “Judeans” but as “Jews.”

Only the esplanade, the underground cisterns, and the wall with its entrances remain today. In the Middle Ages, Cairo, like many other towns with a rich historical heritage, relied heavily on materials salvaged from the Temple Mount (the site of the two temples), because it was a veritable “reservoir” of stones.

The Real Ancient Jerusalem: The City of David

Jerusalem is one of the most passionately revered towns in the world due to its legendary and historical significance. The Latin root for passion is “passio” or “suffering.” And as for the Jerusalem legends, they often feature prophets from the Bible, Jewish tradition, Christianity, and Islam. Thus, the word “passion” has its linguistic roots in these myths and tales.

Jerusalem has many places where the collective memory of its people has been preserved better than in most other cities. Even the tiniest stone in Jerusalem has a story to tell. Everything is a remnant of some past incident, whether real or imagined. But the past is always being reshaped by memory.

A researcher at the turn of the 20th century pinpointed the ancient Jerusalem city, located just south of the medieval city fortifications. Louis-Hugues Vincent, a historian at the École Biblique in Jerusalem, was a devout monk, an archaeologist, and a Dominican priest.

This educational institution was established in the middle of the 19th century to be dedicated to the study of Holy Land antiquities and interpretation. And the location of ancient Jerusalem was the target of this researcher’s quest. The initial settlement was dubbed “the City of David” by him.

The Israelite tribes were said to have been united under David’s leadership in the land of the Canaanites. According to the scriptural timeline, David captured Jerusalem in the year 1010 BC, well before the birth of Christ. But can we really verify David’s existence?

What the Bible states about him is all we have. External evidence, such as stelae carved in the Aramaic language and referring to rulers from the “house of David,” is, at best, equivocal. This evidence shows that David was the progenitor of a family that controlled Jerusalem, but we have no other information about him or his life.

The Consistency of Ancient Jerusalem

Over the course of history, Jerusalem has been an integral part of the Levant, an area that is sometimes referred to as Islamic Syria (but not in the sense of the present nation) or Bilad Al-Sham. Palestine was the name given to the coastal area of the Levant.

The city of Jericho, which was founded in the Fertile Crescent and has been constantly inhabited since 4500 BC for five millennia, is an example of one of the earliest towns in the world.

Cities have moved around in Egypt and Mesopotamia over time. For example, Babylon, which was close to Ctesiphon, served as the capital of the Persian emperors until the 1st century BC. And Baghdad was also close to Ctesiphon, but there is no historical continuity between these three cities.

Even though urban sites in the Levant are rarely abandoned, even during times of devastation, it is the reverse in Egypt, where we witness movement between ancient cities such as Memphis and Fustat, both of which are near the later-founded Cairo.

For instance, in 715 AD, the Umayyads established the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. The mosque was constructed on the site of the former church of St. John the Baptist. This consistency is what makes Jerusalem so special.