The first part of the Peloponnesian War is known as the Archidamian War, spanning from its outbreak in 431 BC until the Peace of Nicias in 421 BC. Its name is derived from the Spartan king Archidamus II, who, despite not being a war enthusiast, led Peloponnesian invasions into Attica until his death in 427 BC. The conflict lasted for ten years and can be divided into four phases:

- Pericles‘ defensive war (until his death).

- Athens’ offensive war after the death of Pericles.

- The Athenian occupation of Pylos and Sphacteria.

- The peace of 421 BC achieved by the Athenian strategist Nicias.

Until the Death of Pericles

The main events in Thucydides’ narrative of the war until the death of Pericles are:

- The first invasion of Attica by the Spartans.

- The beginning of the siege of Plataea by its neighboring Boeotia, Thebes.buy lexapro online in the best USA pharmacy https://rxnoprescriptionrxbuyonline.com/lexapro.html no prescription with fast delivery drugstore

- The plague epidemic in Athens.

Invasions of Attica

The operational plan of the Spartans and the Peloponnesian League involved appearing in Attica every year before the harvest, devastating the fields to compel the Athenians to initiate a struggle in the open field, where they would be at a disadvantage. Meanwhile, Sparta continued to foster discontent among the Athenian allies of the Delian League.

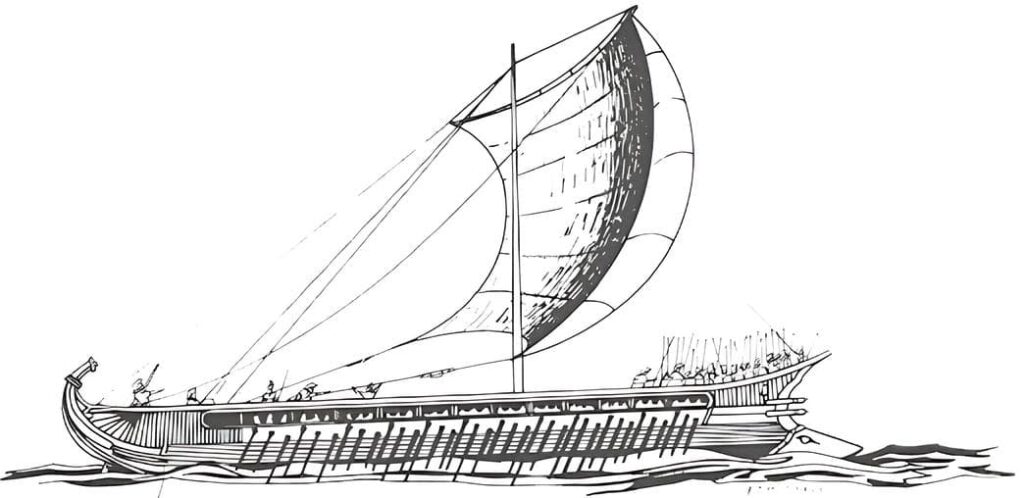

The Athenians knew that the final outcome depended on their fleet, to which four specific missions were assigned:

- Control the maritime routes of the Western Mediterranean through the Gulf of Corinth and around the Peloponnesian Peninsula.

- Harass the Spartans with landings on their coasts.

- Consolidate a series of strategic points crucial to keeping them blocked.

- Isolate the Peloponnesian forces from their allies in Sicily and Magna Graecia.

In 431 BC, two months after the events recounted in the following section, the Spartan army appeared in Attica, and Archidamus attempted, as he had done previously, to get the Athenians to make some concessions. Pericles did not yield. Additionally, the Athenian Assembly enacted a decree prohibiting negotiations with the enemy under pressure of arms.

For greater security, the Athenians sheltered their families and possessions in the Long Walls, from where they could witness the destruction of their wheat fields, vineyards, and olive groves by the Peloponnesians. Archidamus had to withdraw from Attica after waiting in vain for a month for Pericles’ troops to defend their lands and try to expel him. Moreover, he lacked supplies as the Athenians had withdrawn their food reserves and livestock.

Attack on Plataea

Military actions began in 431 BC with Thebes’ attack on the city of Plataea, an ally of Athens and hostile to Theban supremacy in the Boeotian League, which served as an outpost in Boeotian territory. There were significant tensions between the two cities as the Thebans sought to expand the Boeotian League under their leadership and were unwilling to relinquish Plataea.

In the spring of 431 BC, Thebans, aided by a pro-Theban faction from within, attempted to seize Plataea by surprise. The attempt failed, but the frightened Plataeans killed the 330 Theban prisoners who had surreptitiously entered the city, and this massacre incited Thebans against them.

Although the Theban aggression against an Athenian ally tacitly initiated hostilities, the “official” beginning of the conflict did not occur until May, with the Peloponnesian invasion of Attica led by the Eurypontid king Archidamus II.

Subsequent Military Actions

In these early years of the war, Athens displayed intense military activity, as evidenced by various actions such as the annual invasion of the neighboring Megaris region and the expulsion of the Aeginetans from their own island to establish Athenian cleruchs (settlers) under a pact between Athens and Sparta, who settled in the region of Thyrea. The Athenians also aimed for absolute control of the Gulf of Corinth and the maritime route to the Western Mediterranean.

In 431 BC, in accordance with his capabilities and strategic plans, Pericles dispatched a fleet of a hundred triremes to the shores of the Peloponnese. Although it failed in Methone (on the western coast of Messenia), defended by the Spartan general Brasidas, it succeeded in Elis. Brasidas, an atypical Spartan strategist, undoubtedly stood out during the Archidamian War, earning the praise of Thucydides for his military talent and diplomatic skill.

The northwest of continental Greece became a significant theater of operations, where Athens, with the assistance of its Acarnanian allies, attempted to eliminate Corinthian influence. In 431 BC, the same 100 ships that had circumnavigated the Peloponnese seized the Corinthian colony of Soli, ousted the pro-Corinthian tyrant Evarchus from power in Astakos—though he was restored by the Corinthians in the following winter—and diplomatically gained control of the island of Cephalonia, at the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth.

Swift landings in the perioeci territory of Laconia and Messenia were repeated in subsequent years:

- In 430 BC – For details on these actions, refer to the second paragraph of the section “After the death of Pericles.”

- In the summer of 428 BC when, on two occasions, the Athenian fleet ravaged coastal regions in Lacedaemon. Thucydides reflects the Spartans’ concern.

In the spring of 430 BC, 4,000 Athenian hoplites and 300 horsemen, aboard 100 Athenian cavalry transport ships and 50 from Chios and Lesbos, laid waste to the countryside of Epidaurus and attempted an assault on the city, which failed. Following this, they devastated the fields of Troezen, Halieis, and Hermione, cities located on the Acte Peninsula in the northwest of the Peloponnesian Peninsula. The expedition concluded with the conquest and plunder of Prasiae.

The devastation of these three cities, besides undermining Spartan morale, served as a call to Argos to abandon its neutrality and lead the opposition to Sparta in the Peloponnese. Additionally, Prasiae, situated south of Cynuria, was a hotspot in the age-old conflict between Spartans and Argives over the possession of this border region between Laconia and Argolis. The dispute intensified when the Spartans settled Aeginetans there, expelled from their island by the Athenians.

In the summer of 430 BC, there was an attempt at diplomatic rapprochement between Sparta and Persia. A delegation, consisting of Spartans Aneristus, Nicolochus, and Pratodamus, Tegean Timagoras, Corinthian Aristeus, and Argive Polides, was sent with the main mission of securing financial support from the Great King for the Peloponnesian League. The presence of at least two high-ranking Spartans, Aneristus and Nicolochus, descendants of Espertias and Bulis, the two nobles who sacrificed their lives to Xerxes I to atone for the crime against the heralds of the Persian Great King, confirmed Sparta’s readiness to continue the war until the disintegration of the Athenian Empire.

This happened precisely at a time when Athens sought a peaceful resolution to the conflict. En route to Persia, the ambassadors seized the opportunity to persuade the Odrysian king Sitalces to abandon the Athenian alliance, which could be very useful for aiding Potidaea and even for inciting a rebellion throughout Chalcidice, very close to the Thracian kingdom.

However, coincidentally, two Athenian ambassadors were present at the court of Sitalces, who persuaded Sitalces’ son, Sadoch, who had recently granted Athenian citizenship, to hand over the Peloponnesian envoys. The members of the delegation were arrested, taken to Athens, and executed without a prior trial. Thucydides explains the violation of the law that allowed any individual to defend themselves publicly, attributing it to the fear inspired by Aristeus, who was accused of all the troubles in Potidaea and Thrace.

In the late summer of 430 BC, the Spartans and their allies dispatched an expedition of 100 ships, carrying 1000 hoplites, against the island of Zakynthos, located off Elis and an ally of Athens. Led by the Spartan Cnemus, they disembarked and devastated most of the island. As the Zakynthians refused to surrender, they set sail towards the Peloponnese. Thucydides implies that the military campaign was a failure due to Cnemus’ role as the navarch (admiral), considering him the archetype of a Spartan due to his lack of energy and decisiveness.

Zakynthos held significant strategic importance, serving as a stopover in Athenian voyages around the Peloponnese and its location off the coast of Elis, not far from the Peloponnesian naval base at Cyllene. The crucial aspect is the timing of the expedition, which occurred shortly after Athens initiated negotiations for the end of the war—talks that remain unknown as Thucydides does not even outline them, showing little concern for the failed peace attempts.

Athens was going through a challenging moment in the war, not only due to the annual Peloponnesian invasions but also because of the epidemic that was decimating the population. Additionally, there was the rapid depletion of Athena’s treasury, accelerated by the financial drain resulting from the prolonged siege of Potidaea. The authority of Pericles was also questioned by a majority of the people who blamed him for the war’s misfortunes. These criticisms manifested themselves in the temporary deprivation of the strategos position and the imposition of a fine.

The conditions that Sparta set for achieving peace are unknown, but they probably weren’t much different from those demanded before the outbreak of the conflict. The Athenian historian’s silence suggests intransigence on both sides and little success in the diplomatic approach.

The Plague

An epidemic, originating in Ethiopia, was introduced through the port of Piraeus in 430 BC and quickly spread through a city whose dense population lived crowded within the walls in precarious hygienic conditions. Although Thucydides accurately describes the symptoms, the nature of the disease remains a subject of debate among pathologists, considering possibilities such as bubonic plague, typhus, smallpox, and influenza. In three years, 4,400 hoplites and 300 horsemen perished, roughly one-third of both bodies, a casualty percentage presumably also recorded among the general population. Pericles succumbed to the epidemic and died in 429 BC. The epidemic, moreover, recurred in 427 BC.

After the Death of Pericles

The power vacuum left by Pericles was filled by the aristocrat Nicias and the demagogue Cleon (d. 422 BC). The former advocated for an understanding with Sparta to end the conflict, while the latter was inclined toward an all-out war without concessions. This internal struggle affected Athenian foreign policy, which experienced continuous fluctuations as the people were swayed by one leader or the other. The political legacy of the “Olympian” also fell to Eucrates and Lysicles. None of these figures knew how to capitalize on the opportunities that presented themselves to the Athenians to emerge successfully from a challenging war.

Phormion and Cnemus

In the summer of 429 BC, the Spartans implemented a vast and ambitious plan in the northwest, aspiring not only to dominate Acarnania but also the islands of Zakynthos and Cephalonia, and even Naupactus, where since the winter of 430-429 BC, the Athenians had stationed a fleet under the command of Phormion, enhancing their control of the Gulf of Corinth.

The Spartan plan would make it extremely difficult, or even prevent, the Athenians from circumnavigating the Peloponnese and blockading the Gulf of Corinth due to a lack of ports for their ships. However, the Acarnanian campaign, also led by Cnemus, would end in another debacle due to poor coordination among the participants and the inconsistency in Spartan leadership.

The Spartans were more inclined to withdraw at the slightest adversity or setback than to engage in a distant enterprise from which they were not direct beneficiaries. The 47 ships forming the fleet supporting Cnemus couldn’t evade the surveillance of Phormion and were forced to combat at the entrance of the Gulf of Corinth. In the two naval battles, the second of which Phormion won despite a numerical disadvantage of almost 4 to 1, a significant portion of the Peloponnesian fleet was trapped in the gulf. This prevented the Peloponnesian League from participating in the defense of the Peloponnesian coasts, as the consequences of both defeats were disastrous for them.

Subsequently, Phormion took a detour through Acarnania, a region with several territories dominated by Athens’ allies. He returned to Athens via Naupactus, thus complicating the supply of wheat from Magna Graecia to the Peloponnese. Despite his successes, he was accused in court and sentenced to pay a fine, which, being unable to satisfy him, led to his atimia (loss of citizenship). Consequently, he could no longer hold any public office.

Militarily, Athens retained Naupactus, signifying the blockade of the gulf and the Isthmus of Corinth, while almost a quarter of the Peloponnesian fleet had been dismantled and its crews captured or killed. These effects had repercussions on naval activity in the following years. Another no less important development was the naval strengthening of Athenian power in northwest continental Greece at the expense of the Corinthians, as demonstrated shortly after by the expeditions to Acarnania by Phormion and his son Asopius.

Mytilenean Revolt

In 428 BC, the island of Lesbos, which had been one of Athens’ most loyal allies for half a century, defected from the Delian League. This defection had the potential to drag other city-states along and undermine Athenian dominance in Asia Minor. Due to its strategic position in the region of the northern Aegean straits, Lesbos was admitted to the Peloponnesian League, although the Peloponnesians did not provide effective assistance. The Athenians sent the strategos Paches to the island, commanding 1000 hoplites and 250 triremes. He blockaded the two ports of Mytilene and surrounded them with a wall.

As the Athenian punitive expedition incurred significant expenses, Athens had to resort to a wealth tax, eisphora, which provided a fund of 200 talents. Meanwhile, another Athenian fleet circumnavigated the Peloponnese. Due to the harm it inflicted on the perioeci communities of Laconia, the Spartans chose to come to their aid instead of rescuing the people of Mytilene. When Sparta decided to send a fleet of 40 ships under the command of Alcidas, it was already too late. In the Cyclades, the Spartan navarch received the news that Mytilene had surrendered.

The city of Miletus, which sought help from the Peloponnesian League, waited in vain and had to surrender. In the treaty between Paches and the people of Mytilene, the Athenian general pledged not to execute, enslave, or imprison any Mytilenean before the return of an embassy sent by the city to Athens. The ecclesia, at the suggestion of Cleon, decided to punish all Mytileneans severely, advocating for the execution of the adults and the enslavement of the children.

However, in a hastily convened Assembly, the people were persuaded by Diodotus to repeal the cruel decree (psephisma) and replace it with another that only sentenced the leaders of the rebellion to death. It was also decreed that the walls be torn down, only the ambassadors, whose number remains unknown to this day, be executed, autonomy be lost, the fleet be handed over, and all cultivable lands, except those of Mithymna, be confiscated for later distribution among Athenian cleruchs.

The End of Plataea

In 427 BC, the Spartans and their allies marched with their troops to Plataea, which had been under siege since 429 BC. Plataea, an ally of Athens, remained a thorn in the side of the Boeotian League, led by the Thebans. After speeches from both Plataeans and Thebans, five Spartan judges dispatched to Plataea pleased their Theban allies by deciding to execute the 225 defenders who had surrendered (200 Plataeans and 25 Athenians) and enslave 110 women. The city was destroyed, and the lands and small communities dependent on it were annexed by the Thebans (427 BC), who saw their political and economic power increase within the confederation.

The Civil War of Corcyra

The Civil War (stasis) that erupted in Corcyra represented the first incident of dramatic consequences for the internal politics of a city as a result of the interference of the two powers vying for hegemony in Hellas. In 427–426 BC, the endemic antagonism between the Corcyrean (Corfu) democrats and oligarchs degenerated into an open civil conflict when the latter attempted to seize power through violent means and overthrow the democratic government.

The prisoners taken during the battles over the city of Epidamnus had been released, either in exchange for a huge sum for their ransom or due to the promise they made to reconcile their city and Corinth. Corcyra possessed the third-largest fleet of the time, and if it fell into the hands of the Peloponnesians, it would tilt the balance of naval power.

Moreover, the island of Corcyra had significant strategic value due to its location on the maritime route to the Italian peninsula and Sicily. Athens sent its first expedition there in the same year to cut off the Peloponnesian grain supply and the possibility of gaining control of the island. The intervention of the Athenian Nicostratus with his fleet did not resolve the problem, although Corcyra signed an alliance with Athens, replacing the previous epimachia (defensive alliance) for the time being.

The Athenian Occupation of Pylos and Sphacteria

The war was about to take a new and unexpected turn in favor of Athens, amidst the successes and failures on each side. The Athenians had decided to carry out intensive naval activity in the Ionian Sea, aiming to attack Sparta’s allies and seeking to extend their hegemony to Sicily and Magna Graecia.

Athens deployed its fleet there with two specific objectives:

- Isolate the Peloponnese from the wealthy colonies of Italy and Sicily, especially Syracuse.

- Impose political hegemony over the Greek colonies in the West.

The Athenian intervention relied on the old and bitter rivalries that had long faced the Greeks of these western colonies. For a long time, Syracuse had threatened Segesta, Leontino, and Rhegium, among others. Pericles had allied with them against Syracuse and its allies (Gela, Selinunte, Himera, and Locri).

Under the command of Laques, 40 ships appeared between 427 and 426 BC. They returned to Athens with no real success because the Greeks of Sicily gathered in Gela, anticipating Athens’ annexation intentions, and agreed to make peace among themselves. However, the Athenian assembly, following bellicose and megalomaniac leaders, exiled the three strategoi of the fleet, accusing them of being corrupted to abandon the conquest.

On the Peloponnesian coasts, Athens achieved favorable results that it failed to capitalize on. Demosthenes landed on the coast of Messenia to harass the Spartans. His fleet had to anchor in the bay of Pylos due to a storm, a moment the Athenian strategos used for his other two colleagues, Eurymedon and Sophocles, to occupy the Corifasian Peninsula. From there, the Athenians could be in contact with the Messenians.

While most of the ships continued to Corcyra and Sicily, Demosthenes stayed behind with five triremes. The Spartans occupied the island of Sphacteria, located south of Pylos, with the intention of confronting the Athenian detachment. The Athenian fleet that had headed to Corcyra returned from Zante and blocked the two entrances to the bay of Pylos, isolating a significant number of Lacedaemonian hoplites on Sphacteria.

Faced with this dramatic situation, Sparta arranged a truce for the region of Pylos and wanted to negotiate peace with the Athenians. Given the power of the radical Athenians under the leadership of Cleon, the Assembly ordered him to end the situation. Athenian hoplites landed on the island, disarmed the Spartans, and captured 120 Spartiates.

The success of the operation was not Cleon’s but Demosthenes’, the main architect of it, although Cleon claimed the triumph. He took advantage of this victory to triple the tribute of the Delian League and increase the juror fees to three obols, thereby gaining the favor of the people. The Spartan defeat surprised all of Greece. Such a victory over their infantry and, above all, the presence of a garrison in Pylos formed by Messenians from Naupactus and Athenians, posed a significant threat to Laconia due to the potential danger of a helot uprising.

Towards the Peace of Nicias

Cleon and Brasidas

The success at Sphacteria had led Athens’ war faction, led by Cleon, to a program of actions that differed from Pericles’ naval policy, leaning towards land warfare. The conquest of the island of Cythera in 424 BC by Nicias caused serious damage to Peloponnesian trade. The Athenians seized the port of Nisaea. Later, an Athenian contingent attempted the conquest of Boeotia but suffered a major defeat in Delium against Boeotian hoplites who, for the first time, employed the oblique phalanx formation.

The Spartan general Brasidas introduced a new turn to the war, which had hitherto involved ravaging Attica and maintaining a defensive stance in the Peloponnese. They recognized that Athens’ vulnerability lay in Chalcidice and Thrace. To reach these regions, the Lacedaemonians would need to pass through Thessaly, officially an ally of Athens but divided between pro-Athenian and pro-Spartan factions: the common people favored Athens, while the wealthy aristocracy sympathized with Sparta. Brasidas crossed the Isthmus of Corinth, Boeotia, and Thessaly, and arrived in Chalcidice, where he incited the inhabitants to revolt.

The cities of Acanthus and Stagira sided with him, and his most notable success was the conquest of Amphipolis. Thus, Brasidas dealt a significant blow to the Athenians in an area where their empire seemed secure. Thucydides, the historian, and then the strategos responsible for the city’s defense could not prevent it from being taken by Brasidas. This loss was crucial due to its strategic position with respect to Thrace and the Straits (Hellespont and Dardanelles), as Amphipolis provided wood for shipbuilding and contributed financially. Thucydides was punished with ostracism (exile) by the Athenian assembly.

Following the Spartan victory, numerous Chalcidian cities defected from the Delian League, and the rich gold mines of Mount Pangaion came under Spartan control. Athens’ position in Thrace weakened with the loss of other cities like Torone (Toroni). Consequently, the Athenians were compelled to increase tribute quotas (eisphora), leading to the defection of additional allied cities. However, both Athenians and Spartans, represented by Nicias and Pleistoanax, desired peace as soon as possible. The latter were particularly concerned about the prisoners from Pylos, who would be executed if the Peloponnesians invaded Attica again.

Consequently, in the spring of 423 BC, Laconian general Laconian negotiated a one-year truce that seemed to leave a door open to a definitive peace. Thucydides records its contents, which included different local demarcation lines for both forces and their territorial possessions. Certain problematic issues would be subject to arbitration.

However, once the deadline passed, the war resumed in Chalcidice, and intrigues continued. The city of Sicyon defected from the Delian League, and according to the agreement, it should have been returned to them, but Brasidas refused. Nicias managed to win the support of Perdiccas II of Macedonia and Prince Arrhidaeus of Lynkestis, gaining some advantage in the north. Cleon presented himself with a strong contingent and achieved some victories, including the conquest of Torone, but as he approached Amphipolis, the Spartans dealt him a severe defeat. Cleon and Brasidas died in the Battle of Amphipolis in 422 BC.

The Peace of Nicias

The deaths of Cleon and Brasidas removed two staunch supporters of war from the political stage, allowing Pleistoanax and Nicias to resume peace negotiations. The events in Delium and Amphipolis shifted the spotlight in the direction of the war and, therefore, in Athenian politics, to the aristocrats led by Nicias, who wanted to return to Pericles’ plan as the war was ruining the agricultural economy. Nicias faced opposition from radical Democrats Hyperbolus and Peisander. Sparta also desired peace. Among other things, they wanted the return of the 120 prisoners from Sphacteria (island), as the diminishing number of Spartiates was a concern. In the early days of April 421 BC, peace was signed for a duration of 50 years. The key points recorded by Thucydides were:

- Athens and Sparta would return to the situation before the war and should therefore reintegrate everything conquered during it.

- The Spartans and their allies would regain Pylos, Corcyra, Cythera, Methana, Pteleum, and Atalanta.

- Exchange of prisoners.

- Release of prisoners by both sides.

- Recognition of the autonomy of the Sanctuary of Delphi.buy viagra online in the best USA pharmacy https://viagra4pleasurerx.com/ no prescription with fast delivery drugstore