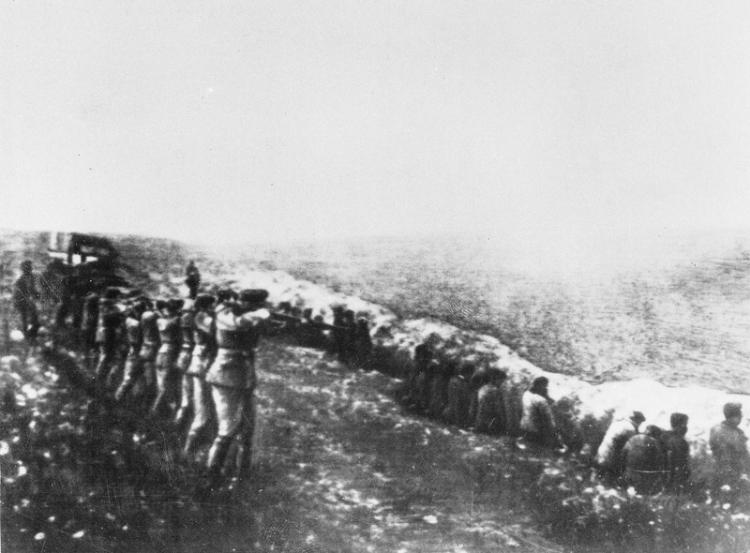

When discussing the genocide of European Jewry, the Babi Yar or Babyn Yar ravine is one of the massacres that stands out. The Nazis killed 33,771 Jewish children, women, and men in under 36 hours on September 29 and 30, 1941, in Kiev, Ukraine. This was more than they had killed in all of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps combined.

Freedom to kill

The massacre at Babi Yar (“Old Women’s Ravine”) in Ukraine, west of Kiev (or Kyiv), was the first major destruction operation after Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, which broke the German-Soviet Treaty of August 23, 1939.

Each Wehrmacht unit that invaded the Soviet Union was followed by “Deployment Groups,” or Einsatzgruppen. These groups were run by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), which Reinhard Heydrich created in September 1939 by combining the Gestapo and Kripo with the Reichssicherheitshauptamt.

Beginning in August of 1941, these groups were given wide rein to brutally murder the Jewish civilian population hiding behind the war lines.

The Jewish population

There were around 5 million Jews in the Soviet Union at that time, with the vast majority residing in the western provinces of the past Tsarist era. Cities were where they were most likely to be found. At this time, 160,000 Jews made up over a quarter of Kiev’s population.

The Red Army’s mobilization at the end of June 1941 and the policy of evacuating a variety of Soviet citizens enabled 100,000 Jews to depart Kiev by September. During the time of the German-Soviet Pact, no one knew about how the Nazis treated Jews in Germany and the other places they took over.

Time bombs and a large fire

As they advanced on Kiev on September 19, 1941, German forces committed a series of horrific atrocities. The Khreshchatyk Street government buildings were demolished by the time bombs placed by the NKVD (a ministry of the Soviets) and the Red Army before they withdrew. The time bombs started a massive fire that raged for five days across the heart of the city.

As the Bolsheviks who committed these bombings were seen by the Nazis as the agents of the Jews (and vice versa), an order to punish them was issued on September 28. People who spoke Yiddish in Kiev and the surrounding area were told to gather in a street near the Jewish cemetery at 8 a.m. on September 29, the holy day of Yom Kippur, with their “identity papers, money, valuables, warm clothes, underwear, and other belongings.”

The notice was written in Russian, German, and Ukrainian on a white background with dark letters. Those who failed to appear would be put to death.

Destination ravine

The Jews of Kiev proceeded to the meeting spot designated by the Nazis, certain that they would be transported or put to work at a nearby freight depot next to the gathering place. But the Jews of Kiev were not deported and rather had to undress, leave their belongings, and walk to a ravine nearby.

All of the Jews were killed by Paul Blobel’s Kommando 4A of the Einsatzgruppen’s Group C and two battalions of the Ukrainian auxiliary police unit. Until 1943, hundreds of Jews, Gypsies, Soviet captives, and Ukrainian patriots were killed in this same valley. The Nazis had the bodies burned and the Soviet prisoners of war covered the mass grave before they withdrew in November 1943.

After the “Great Patriotic War” (1941–1945) was over with victory, Jews who were now just “peaceful Soviet citizens” were still not allowed to have their persecutions discussed openly. This included the Babi Yar Massacre as well. However, witness statements were growing rapidly, particularly in the Yiddish language.

The accounts of survivors

For instance, there were the accounts of survivors like Dina Pronicheva, who managed to free herself from a mound of bodies without injury, and the accounts of war journalists Vasily Grossman and Ilya Ehrenburg, which were collated by Lev Ozerov in The Black Book. Dina Pronicheva testified at the Soviet military tribunal in Kiev in January 1946, when the perpetrators of the atrocities were on trial. Babi Yar. Context (2021), a film by Sergei Loznitsa, features this testimony.

The Soviet Government considered erasing the massacre’s location as early as 1946. A brick business had been dumping its waste into the ravine, and the Jewish cemetery had been demolished, but all that changed in March 1961 when a dam burst and flooded the Babi Yar district.

At that moment, discussions concerning Babi Yar became public. After visiting the site of the forgotten ravine in 1961, Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko said, “Over Babi Yar there are no monuments.” By reaffirming their Jewishness, the poet was restoring their dignity. In 1976, a huge memorial to the Babi Yar Massacre was built in the strict Soviet realism style, but it didn’t actually say anything about Jews.

Until the fall of the Soviet Union and Ukraine’s independence in 1991, neither the Jewish identity of many of the victims nor the cooperation of certain Ukrainians with the Babi Yar massacre was acknowledged publicly. Yet, more victims claim a place in the memory of the Babi Yar Holocaust.

Today, it’s not the lack of Babi Yar monuments that is unexpected; rather, it’s the abundance of them: about thirty in all. Constructing a memorial center for Babi Yar has been discussed since 2000. All of these initiatives have been, and still are, the subject of heated debate.

The television tower was built next to the ravine that had been turned into a park, and on March 1, 2022, Russian missiles fired at this tower. Ukraine’s then-President Volodymyr Zelensky strongly condemned the efforts to cover up the Soviet invasion and bombing of Babi Yar.

Bibliography

- Ray Brandon, Wendy Lower. (Book) “The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization.”

- The Washington Post. “Babi Yar’s Memorial In Music.”

- The Holocaust Chronicle. “The Holocaust Chronicle: Massacre at Babi Yar”.