From July to November of 1916, the Allies and the Germans fought in the Somme region of northern France in the bloody and protracted Battle of the Somme. The British first engaged some 40 tanks on September 15 at Flers, and the ensuing bloodbath was a turning point in the war. But this initial major Franco-British offensive, led by General Foch and Douglas Haig, did not result in any significant Allied advances on the Western Front (contrary to the expectations of the general staff). Joffre called off the offensive on November 18, 1916, due to bad weather, the exhaustion of the troops, and the small amount of territory gained.

What was the goal of the Battle of the Somme?

According to the command, the lack of resources was to blame for the failure of the Allied offensives in 1915. Generals believed they could win with heavy artillery preparations, which would clear the way for the advance of the troops as production of guns and shells increased. On December 6, 7, and 8, 1915, the Allies convened at Chantilly, in the French Grand Quartier Général under the command of General Joffre, with this goal in mind.

Each of the major players in World War I—the French, the British, the Italians, and the Russians—had the same idea: to launch an offensive at the same time on multiple fronts. The Russians would launch a general attack in the east; the Italians would launch an attack on the Isonzo; and the French and British would launch a massive offensive on the Somme at the end of spring or the beginning of summer 1916. At the same time, the Germans, influenced by Falkenhyan, decided to “bleed the French army dry” by leading an assault on Verdun.

The Battle of Verdun altered the original plan

Due to the unexpected start of the Battle of Verdun on February 21, 1916, plans were severely hampered. While the Somme offensive was planned as a joint French and British effort in which both sides would play an equal role, the French demanded in February that the British contribute more to the offensive through the head of the French Military Mission to the British Army. The attack’s front was also drastically shortened, from 70 to 40 kilometers, with the British portion reaching 28 kilometers; the Battle of the Somme would henceforth be fought primarily by the British.

The area of Albert, which the Allies control, and the surrounding area of Péronne (controlled by the Germans), would be where the operation would take place. There was a lot of room for interpretation in the objectives, which Jean-Jacques Becker claims were as much about wearing down the German army as they were about finding the decisive battle that would lead to final victory.

Harmful attack, but not much accomplished

Several days of intensive artillery preparation culminated in an assault on German defenses by French and British armies on July 1, 1916. Although the French VIth saw some success in the south, the British army suffered catastrophic losses, with 10,000 dead and 60,000 wounded by July 1. The attackers were met with partially intact defenses and German machine gun fire despite the extensive preemptive bombardment.

The battle, which spanned a significant amount of time, can be broken down into three distinct parts: the initial offensive, which occurred from July 1 to 20, the long stagnation that occurred from July 20 to September 3, and the slight advancement that occurred from September 3 to November 18. The British lost 420,000 men, including over 100,000 dead, and the French lost 200,000 men, including over 100,000 dead, for an advance of only a few kilometers. Over 500,000 German soldiers died in the conflict.

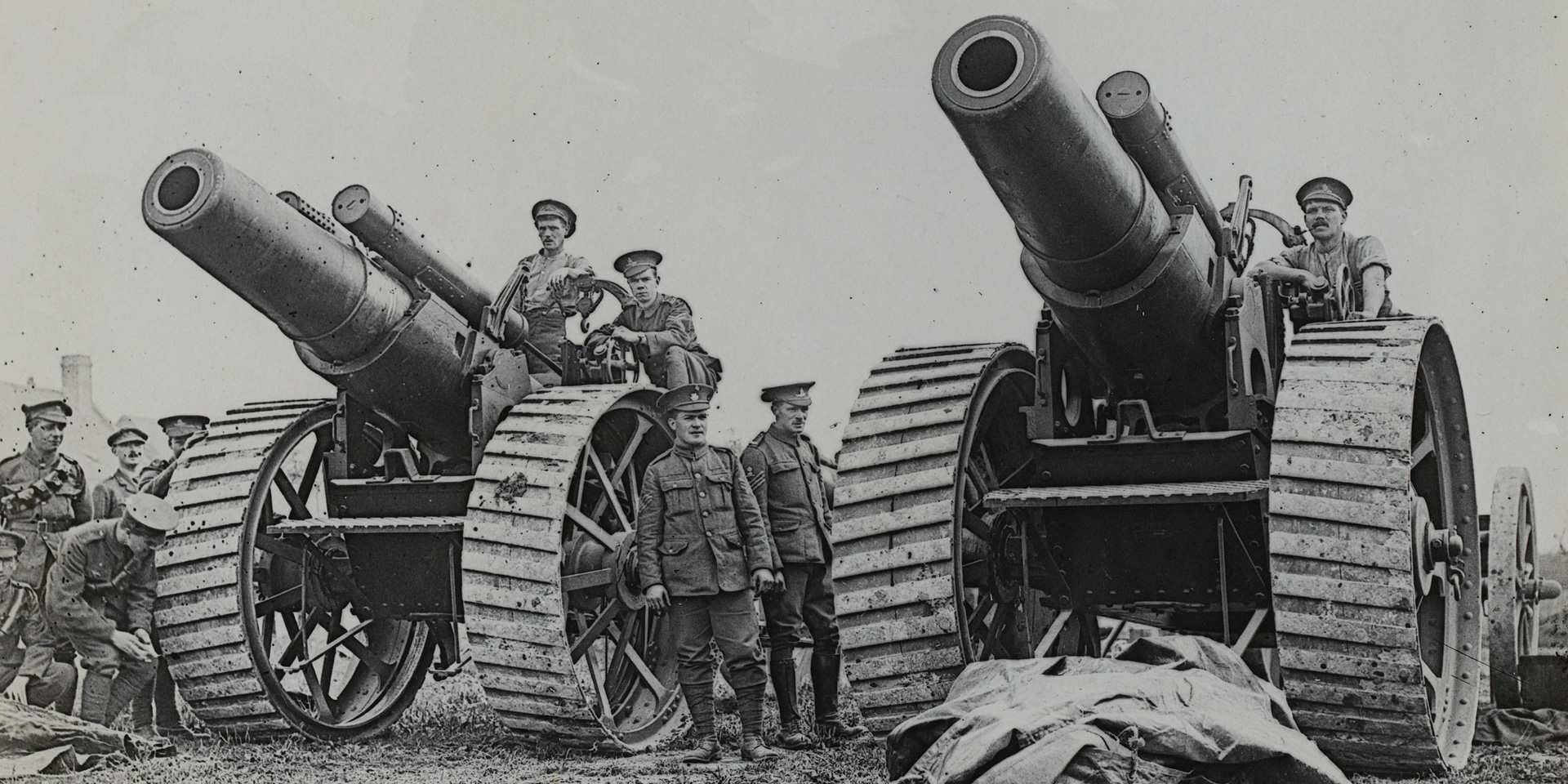

The British Army deployed tanks (Mark IV) for the first time on September 15, 1916, at Flers. Many of them were unable to reach the front lines, but others made remarkable progress. In spite of this, there weren’t enough of them, and they were too sluggish and unreliable.

Its many flaws, especially its slowness (barely 6 km/h on the road), gave it an effect that was more psychological than real, with most of the examples involved in the fighting being destroyed or captured. This was also true of the French and German tanks that appeared a few months later. A few months later, tanks finally became a game-changer.

By the end of 1916, it appeared that the Somme offensive had failed because the enemy lines were not breached. With Germany’s continued occupation of northeastern France, the balance of power remained in the hands of the central powers. Worse, it appeared that neither side could win the war decisively.

Battle of the Somme; a turning point

The Battle of the Somme was a turning point in the Great War for a number of reasons. While the Battle of Verdun is not prominent in German accounts of the war, the Battle of the Somme is. While fighting on French territory, German soldiers saw themselves as defending their homeland from the British invaders and took a defensive position in underground shelters.

The French were discouraged after the failure of the Somme, and this fed a weariness that began at the end of 1916 and was expressed more forcefully in 1917. The volunteers, who made up the bulk of the troops sent and were decimated on July 1, 1916, were replaced by conscripts, whose formation had begun at the start of 1916, and the Somme marked the beginning of the end for the volunteer army.

The French and British worked together exceptionally well on the Somme, marking a turning point in the war. The French and British armies had to employ liaison officers to facilitate better communication between the two sides as liaison tactics began to be put into practice. The Somme campaign failed and cost a lot of lives, but it showed Allied commanders that they needed to work together better and train harder to defeat the Germans. It’s true that the Allies were able to learn from this massive material battle, especially with regards to the use of artillery, which ultimately led to their victory in 1918 despite the terrible weather and serious tactical errors.

Memory of the Battle of the Somme

British people’s recollections of World War I will always include the bloody Battle of the Somme. The first day of the offensive was the bloodiest day in British history, and many accounts detail the carnage that ensued. When the Scottish lieutenant and his two men finally reached the German lines, the man in charge is rumored to have exclaimed, “My God, where are the rest of the boys?”

Also quickly remembered was the Somme Battle. The Thiepval (Somme) Memorial, by Edwin Lutyens, was built between 1928 and 1932 at the behest of the British government. The monument, which stands at 45 meters tall and is shaped like a triumphal arch, honors the 73,367 British and South African soldiers who lost their lives on the Somme. Nearly 160,000 people visit the memorial annually, and it is located next to a military cemetery that adheres to British standards, meaning that all names are engraved on uniform steles regardless of the person’s rank or grade.

In addition, the “circuit of remembrance” of the Battle of the Somme has been developed, making it possible to see the scars left by the Great War on the landscape and to see the most significant memorials to the conflict: Somme commemorations have recently taken place at the Ulster Tower (Irish memorial) and the ANZAC memorial (Australian and New Zealand memorial).

TIMELINE OF THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

The British failed on July 1st, 1916

The Allies began their assault early in the morning after several days of artillery preparation were delayed, in part, by bad weather. The British, carrying more than 30 kilos of equipment, moved at a snail’s pace because their command didn’t want them to disperse or think about the decimated German forces from the previous days’ bombardments. The majority of British casualties were the result of German machine gun fire.

July-August 1916: The slow progression

The British command wanted to halt the attack on the Somme front after the disastrous results of the July 1st offensive, but Marshal Joffre, commander-in-chief of the French armies, refused. During the subsequent two months of attacks and counterattacks, both sides made only minimal gains (at Langeval Wood for the British and Flaucourt Plateau for the French, respectively) and suffered significant casualties.

Movement of German Troops

However, the German general staff was concerned that the front lines on the Somme had been breached. As a result, in the month of July, the decision was made to pull thirteen divisions back from the Verdun front and two from the Ypres sector. This relieved some of the stress on the Allies at Verdun. In the weeks that followed, other divisions were scheduled to be deactivated as well. The German writer Paul Zech, who survived Verdun and was sent as reinforcement to the Somme front, testifies in a letter, “Here, everything is brought to its extreme: hatred, dehumanization, horror, and blood (…).” I don’t know anymore what can happen to us.

September-October 1916: intensification of the allied offensives

Several German positions were quickly taken despite the persistent rain and the battlefield’s transformation into a quagmire. On September 9, the British recovered Ginchy, in particular. On September 15th, they deployed their first tanks, which they dubbed “tanks” Mark I, with mixed results due to their clumsiness, but which did allow them to seize a number of positions (Courcelette, Martinpuich…). The French were successful in capturing large portions of territory from the Germans and capturing thousands of prisoners. On September 25th, the British and the French launched a combined offensive that would continue until September 28th. They allowed the Allies to retake Combles and Thiepval and strengthen their positions, but their strength waned in October.

November 1916: Against all odds, the end of the battle

However, despite some Allied victories in November, the fighting appeared to stall. The weather turned bad in the second half of the month, bringing icy rain, blizzards, and snow to the soldiers and effectively halting any offensives. This, oddly enough, was the catalyst for the end of the Battle of the Somme, as on November 21, General Haig, commanding the British army, decided to end the offensive. On the 11th of December, 1916, General Foch, who was in command of the French army on the Somme, did the same thing. On December 18, French Army Chief of Staff Marshal Joffre declared an end to the Somme offensive. The primary goals of Bapaume and Péronne were not accomplished by this war of attrition, which resembled Verdun.