Scientists from the University of Cambridge and the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe have reconstructed the most complete picture to date of how mid-14th-century climate changes set the stage for the most devastating pandemic in European history. Their research shows that volcanic eruptions around 1345 triggered a chain of events that led to the emergence of the so-called Black Death.

We examined the period preceding the Black Death from the perspective of food security systems and recurring famines, which was important for understanding the situation after 1345. We wanted to consider climatic, ecological, and economic factors together to more accurately understand what exactly triggered the second plague pandemic in Europe.

Martin Bauch, Historian of medieval climate and epidemiology at the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe

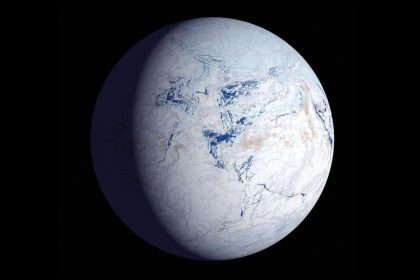

According to the researchers, volcanic activity led to noticeable cooling. For several consecutive years, temperatures remained below normal due to volcanic aerosol in the atmosphere, causing crop failures and famine in many Mediterranean regions.

Professor Ulf Büntgen extracts tree samples in the Pyrenees for climate analysis. Photo: University of Cambridge

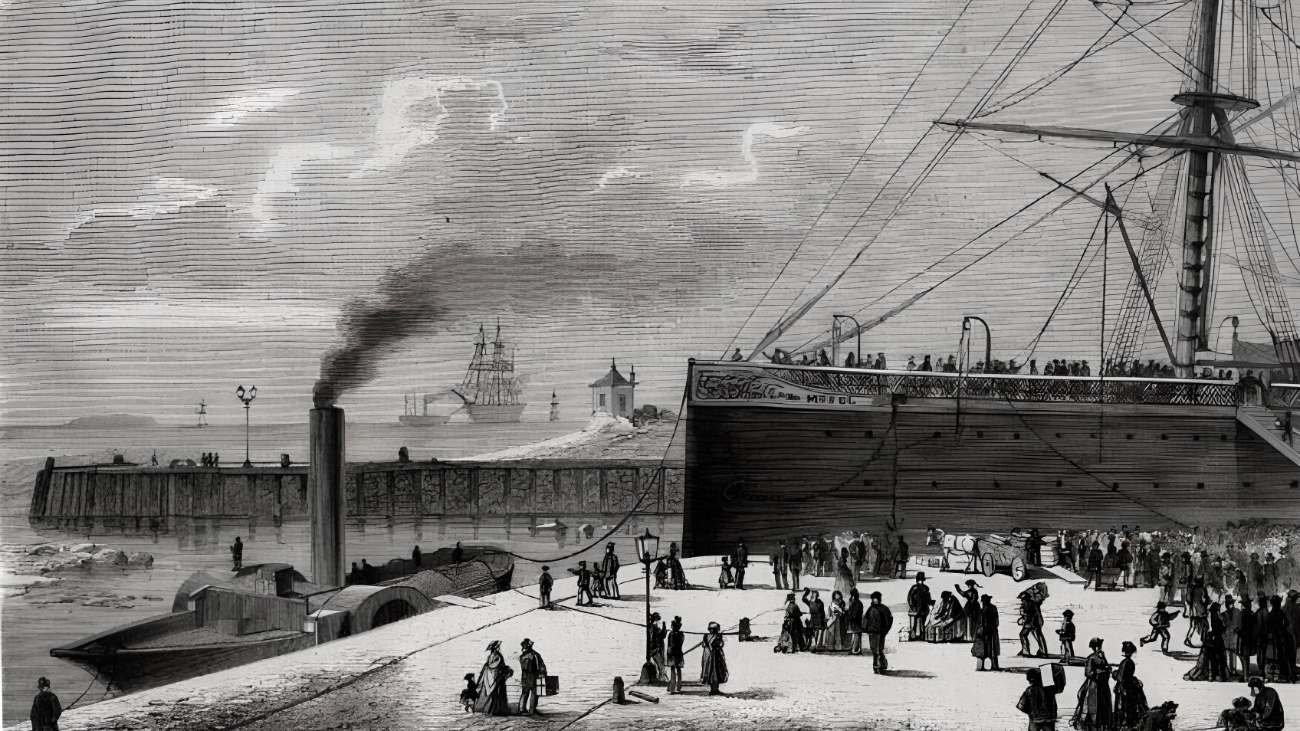

To avoid mass starvation and social unrest, Italian maritime republics—Venice, Genoa, and Pisa—intensified grain shipments from regions around the Black Sea under Golden Horde control. These trade routes saved the population from starvation, but simultaneously became channels for spreading the deadly infection.

For more than 100 years, these powerful Italian city-states had been building long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and Black Seas, which allowed them to deploy an extremely effective famine prevention system. But ultimately, it was this system that inadvertently led to a far more massive catastrophe.

Martin Bauch

Along with grain, ships most likely transported fleas infected with the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Upon reaching Mediterranean ports, they became disease carriers and launched the first and deadliest wave of the second plague pandemic, which between 1347 and 1353 claimed the lives of millions. In certain European regions, mortality reached nearly 60%.

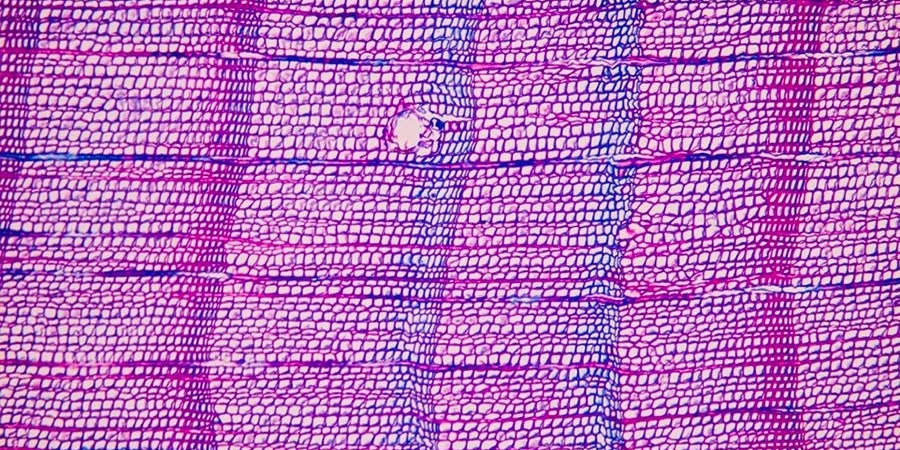

The scientists emphasize that this is the first study to directly link data on climate, agriculture, trade, and the emergence of the Black Death. To achieve this, they used information from tree rings in the Pyrenees, where so-called blue rings indicate unusually cold and wet summers in 1345–1347, as well as medieval written sources that mention dark eclipses and anomalous cloudiness.

So-called blue tree rings in the Pyrenees. Photo: University of Cambridge

The study’s authors note that not all European cities suffered equally. For example, major centers like Milan and Rome likely avoided the epidemic because after 1345 they didn’t need grain imports and weren’t involved in risky trade chains.

The researchers consider the events of the 14th century an early example of how globalization can amplify the consequences of climatic and biological threats. According to them, against the backdrop of modern climate change, the risk of zoonotic diseases—those transmitted from animals to humans—and new pandemics will only increase. This means that lessons from the past may be useful for assessing future threats.