Claude of France (1499-1524), daughter of a king and first wife of Francis I, was known for her great charity, kindness, and gentleness toward everyone. Her motto, “Candida candidis” (pure among the pure), symbolized her purity and innocence, accompanied by an image of a wounded swan pierced by an arrow. She became Duchess of Brittany in 1514 and Queen of France in 1515, holding the titles of Countess of Soissons, Blois, Coucy, Étampes, Montfort, and Duchess of Milan. Claude died prematurely at the age of 24, after giving birth to seven children, including the future Henry II.

Claude’s Royal Childhood

Claude was born joyfully on October 13, 1499, in Romorantin, the daughter of King Louis XII and Queen Anne of Brittany. Her father, overjoyed, declared her “duchess of the two most beautiful duchies in Christendom, Milan and Brittany.” She was cherished, living alongside her parents and becoming the focus of Easter celebrations in 1505.

From an early age, her parents planned her marriage, which led to one of the greatest conflicts between them. As Brittany was to be her inheritance, it was a significant dowry.

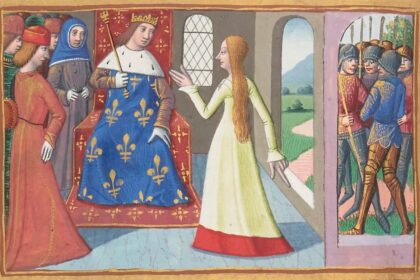

Her mother, Anne, shortlisted only a few suitors, focusing on Charles of Ghent, the future Charles V, who was four months younger than Claude and heir to the Netherlands, Artois, Franche-Comté, Austria, Hungary, Aragon, and Castile. However, there were risks involved. Louis XII then promised Claude’s hand to Francis of Angoulême, the heir presumptive to the French throne, who would defend France’s interests. But Anne detested this lively boy, and she equally despised his mother, Louise of Savoy, who always promoted her son.

Louis XII did not oppose his wife openly, but secretly, in April 1501, he had a declaration drawn up stating that any marriage agreement for Claude other than with Francis of Angoulême would be invalid.

The Treaty of Blois, signed in September 1504, concerning Claude’s engagement to Charles, revealed a dowry that included Milan, Genoa, Asti, Brittany, Blois, Burgundy, Auxerre, Mâcon, and Bar-sur-Seine. Anne did everything to ensure the marriage took place, but the ailing king expressed his desires in letters patent in May 1505. When Anne prepared to leave for Brittany, threatening to take Claude with her, Louis XII spread hostile rumors about Charles of Ghent across the kingdom, causing the people to demand Claude’s marriage to her cousin Francis, “who is wholly French.”

Louis XII had his way. The betrothal took place on May 21, 1506, and Anne of Brittany was forced to attend, despite her displeasure. Claude, barely six years old, dressed in brocade and gold, was carried to the ceremony. She was sweet, pious, and not particularly beautiful; she inherited her father’s nose and her mother’s limp but was even shorter. She also had a slight strabismus and, over time, became overweight, which worsened with her pregnancies.

As time passed, Francis was now 19, and Claude was nearing 15. Although they were still not married, they had known each other for a long time, and Claude had no fears on her wedding night in May 1514. However, the marriage was sad, with everyone in mourning as Anne of Brittany had just died. Three months later, Louis XII followed. Claude was left with no family, only her royal husband.

A Queen on the Sidelines

Hoping for support from her mother-in-law and sister-in-law, Claude found herself alone in her new family. Louise of Savoy and Marguerite of Navarre formed a tight bond around Francis. Louise had hoped for a more beautiful and intelligent wife for her son, someone worthy of his qualities. Claude, viewed as an outsider, was merely tolerated, and the welcome she received was far from warm. In the end, Louise accepted Claude: she posed no threat, and the union was prestigious, as Claude was the eldest daughter of the King of France. Additionally, her dowry was impressive: she held Brittany and the Duchy of Milan.

Claude remained discreet, always in the background. She accompanied her husband to his coronation in Reims and was seen on a platform during their official entrance into Paris, though she would not be crowned until May 1517. At that time, she was already pregnant, and on August 15, she gave birth to a daughter, Louise. Meanwhile, Francis was waging war in Italy, with Louise of Savoy acting as regent and Marguerite serving as ambassador.

Claude faded into the background. She was not strong, nor did she possess the brilliance or wit of the other two women. She had no court or clientele of her own and was simply “a vessel for securing the dynasty.” Even her children were taken from her care, with Louise of Savoy overseeing everything, including the nursery, the care of the children, their deaths, and future alliances.

At least one positive aspect was that the king did his conjugal duty willingly. He did not reject her and admired their children. While he had mistresses, he treated Claude with kindness and kept his extramarital affairs discreet. No royal mistress was ever officially acknowledged at court.

Claude of France’s Children

During their ten years together, Claude gave birth to seven children. As she endured these successive pregnancies, her health deteriorated. She became weak, gained excessive weight, and eventually became unable to move on her own. Despite her condition, she accompanied the king on his travels, as a queen needed to be seen by the people, as a symbol of peace. Francis I loved to travel and attend festivities. Soon after their first child, Louise, was born in August 1515, Claude joined Francis in the south, where he had just triumphed at Marignano.

In early 1516, they stopped near Marseille at Sainte Baume, and by October 1516, their second child, Charlotte, was born. In the spring of 1517, Francis set out again on a year-and-a-half-long journey. During that time, Claude gave birth to the Dauphin, François, in February 1518 (he would later become Duke of Brittany as François III). They traveled to Brittany and Nantes, where Claude learned of her first daughter’s death, but it was Louise of Savoy who returned to Amboise to organize the funeral.

Continuing their royal tour through Vendôme and Chartres, Henry (the future King of France) was born in March 1519 at Saint-Germain. The court traveled to Châtellerault in the winter of 1519-1520, and then to Cognac for three weeks of festivities in February 1520. The negotiations for the Holy Roman Empire against Charles V began, including the famous Field of the Cloth of Gold in June 1520. Claude, always present, was seven months pregnant at the time (the ambassadors were astonished by her size), and she endured the ceremonies, tournaments, and banquets with great difficulty. Madeleine was born on August 10, 1520 (she would marry James V and become Queen of Scotland in 1537).

Travel ceased due to financial difficulties and the king’s poor health. Once Francis recovered, Claude made a pilgrimage to Notre-Dame de Cléry to thank the Virgin for her husband’s recovery. Although they might have expected the births to stop, another child, Charles, was born in January 1522, followed by Marguerite in June 1523 (who would later become Duchess of Savoy through her marriage in 1559 to Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy).

Tributes to the Queen of France

Exhausted, Claude remained bedridden, her face covered in skin lesions. She was not dying from syphilis, as rumored, but from sheer exhaustion. Francis kissed her one last time on July 12 before departing for a campaign in Provence.

Louise of Savoy and Marguerite, notified of her condition, were still in Bourges when Claude died on July 20, 1524, in Blois. They arrived too late.

The queen was mourned. Louise had come to appreciate her for her discretion and devoted herself to raising Claude’s six children with great tenderness. Marguerite praised her virtues and grace. Francis realized that he had loved her deeply, saying, “I never thought the bond of marriage ordained by God would be so hard and difficult to break.”

Claude was a popular, kind, and simple queen, leaving behind nothing but her children and a sweet, juicy fruit—the “Reine Claude” plum. Numerous eulogies were given, describing her as “one of the most honorable princesses ever to walk the earth and the most beloved by all, both great and small. If she is not in Paradise, then few will ever go there.”