At the end of the 17th century, during the reign of the Sun King, France was flourishing. Its economy was booming, and the Triangular Trade was in full swing. More and more slaves from Africa were being sent to the American colonies. They worked in sugar cane plantations, which were of great importance to France. In March 1685, Louis XIV promulgated a historic royal ordinance that defined the legal status of slaves in the Caribbean colonies.

The “Code Noir” was drafted by Colbert, who was the Secretary of State for the Navy and the chief minister of the king for 20 years. This text provided a clear legal framework for practices already in place in French overseas possessions and laid the foundation for French colonial law. The Code Noir continued to be in effect until the second abolition of slavery during the French Second Republic in 1848.

There were several notable slave revolts and acts of resistance against the conditions imposed by the Code Noir, particularly in the French Caribbean colonies. The most famous of these revolts was the Haitian Revolution, which ultimately led to the establishment of Haiti as an independent nation.

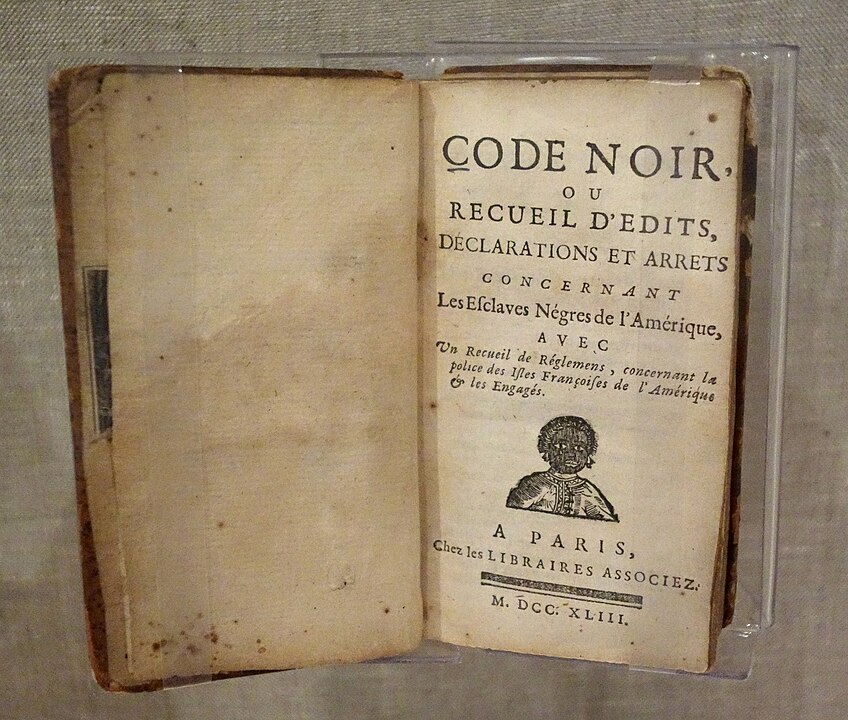

What Is the Code Noir?

The Code Noir is the name given to the royal decree of March 1685 concerning slaves in the French West Indies. Its aim was to specify and regulate, for the first time, the “master-slave” relationships in the Caribbean. It granted slaves an intermediate status, between a free person and movable property, with rights and, most importantly, duties. It recognized slaves as “beings of God” without granting them separate legal personalities.

The text was initially applied in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Saint-Christophe. It was later extended to Saint-Domingue in 1687 and Guyana in 1704. From the 18th century onwards, additional texts modified, supplemented, and tightened the original edict. The term “Code Noir” started to be used to refer to various regulations related to slavery and even French colonial law as a whole.

Who Wrote the Code Noir?

Code Noir was written by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who actively promoted the development of trade and industry as Minister of State for the Navy under Louis XIV and one of the king’s prime ministers for 20 years. Colbert was responsible for drafting the text, which aimed to establish the legal framework for the status of slaves in the colonies. In writing this text, Colbert was inspired by reports on French estates written a few years earlier.

As Colbert died in 1683, the final touches to the text were made by Colbert’s son Jean-Baptiste Antoine Colbert de Seignelay. In March 1685, the king issued the royal decree. Additional edicts concerning Mauritius, La Réunion and Louisiana, among others, were issued in the early 18th century, so in reality it is more accurate to speak of “Codes Noirs”.

Why Was the Code Noir Written?

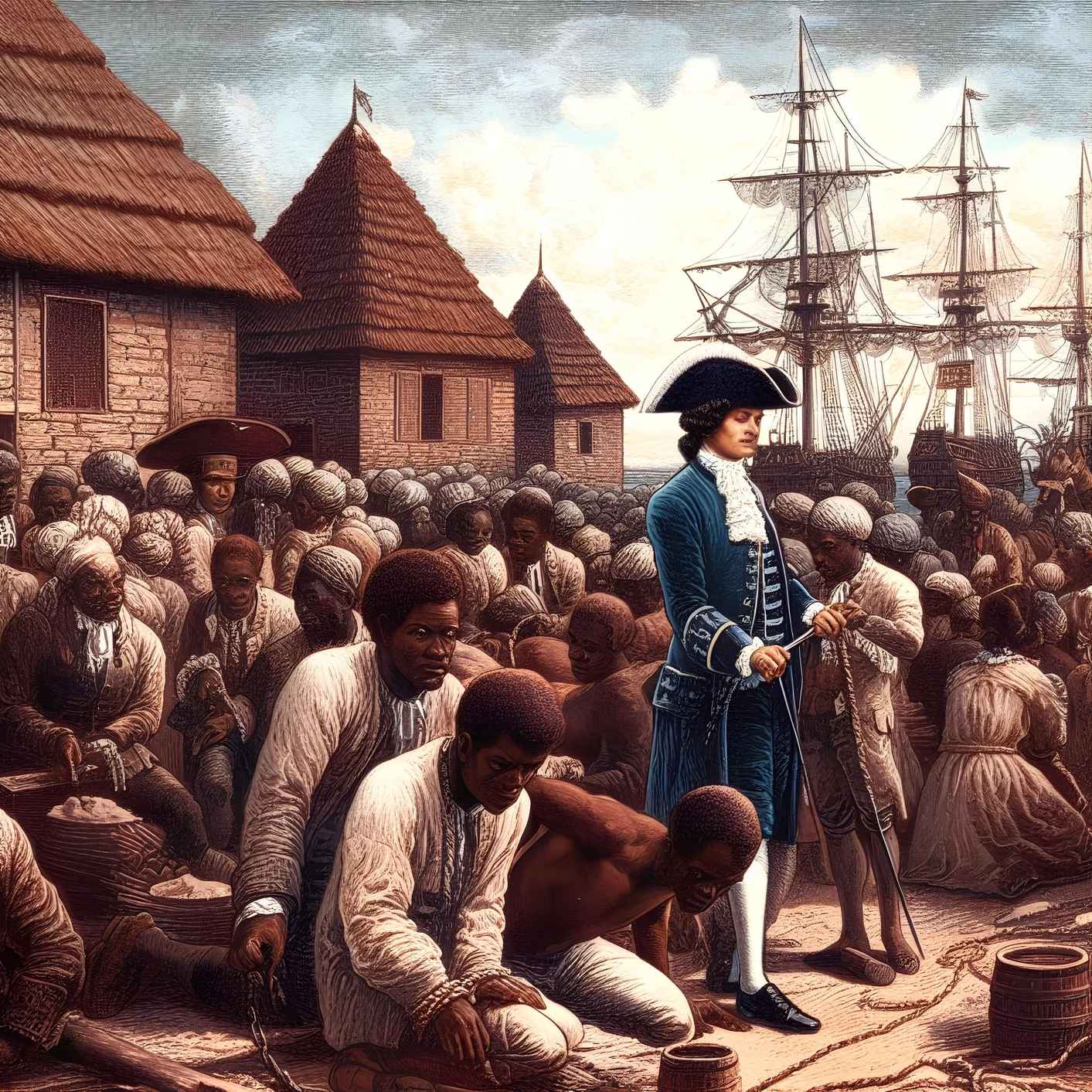

In 1685, France was a major European power in a fierce competition for supremacy in maritime trade. To achieve this, it aimed to make sugar cane cultivation the center of its economic development. But it needed a workforce to exploit the resources of the Caribbean. Like Portugal, England, or Spain, France resorted to the triangular trade. It chartered ships from slave ports to Africa, exchanged goods for slaves and then transported them to the Americas to work on plantations.

Slavery was illegal in the metropolis at the time but widely practiced in the colonies without any legal regulation. The Code Noir therefore aimed to bring order to the relations between owners and slaves in overseas territories. It also reaffirmed the sovereignty of the state and strengthened its control over sugar cane cultivation.

What Does the Code Noir Contain?

In a preamble and sixty articles, the Code Noir regulated the condition of slaves in the French colonies. For the first time, slaves had some rights but were subject to numerous prohibitions. Article 44 of the Code Noir declared slaves as “movable property” that could be bought or sold, stating, “We declare slaves to be movable and as such to enter the community.” In the 17th century, an individual’s legal personality was not inherently linked to their humanity.

Therefore, it was not contradictory for a slave to be considered both a being with a soul and an object. The text governed various aspects of the lives of slaves, including work, religion, housing, property, offenses, and manumission. While it granted some rights, slaves were still unable to own anything (Article 28: “We declare that slaves cannot have anything of their own that is not their masters’) and could not testify in court; they remained subject to their owners.

The Code Noir also served as a means to reaffirm the Christian faith in the colonies. The practice of the Protestant faith was prohibited (Article 5), and Jews were expelled from the islands (Article 1).

We forbid our subjects of the so-called reformed religion to disturb or prevent our other subjects, even their slaves, from the free exercise of the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion, on pain of exemplary punishment.

Article 5.

Code Noir contained provisions related to religion. It required enslaved individuals to be baptized as Catholics and to receive religious instruction. It also regulated religious practices within the enslaved population.

Did the Code Noir Improve the Living Conditions of Slaves?

Starting in 1685, slaves were required to be educated and baptized. They were thus considered Christians. They were entitled to rest on Sundays and during holidays. They could marry in the church with the consent of their masters and be buried in a cemetery (Article 10). Owners were obligated to provide them with food (Article 22: “Masters shall be required to provide their slaves aged ten years and above with two and a half Paris measures of cassava flour every week”), clothing (Article 25), and care for elderly or sick slaves (Article 27).

Additionally, slaves and their families could not be sold separately. However, the Code Noir legalized corporal punishment on slaves. They could be beaten, branded with a hot iron, or have their ears cut. Masters were not, however, allowed to arbitrarily kill a slave (Article 43).

Each week masters will have to furnish to their slaves ten years old and older for their nourishment two and a half jars in the measure of the land, of cassava flour or three cassavas weighing at least two-and-a-half pounds each or equivalent things, with two pounds of salted beef or three pounds of fish or other things in proportion, and to children after they are weaned to the age of 10 years half of the above supplies.

Article 22.

The death penalty applied to a slave who struck his master or was sentenced to escape for the third time. Despite the introduction of the Code, the living conditions of slaves remained very harsh. Improvements and increased control over the actions of owners would have to wait until the reign of Louis XVI.

When Was the Code Noir Abolished?

The Code Noir remained in effect throughout the slave trade until the abolition of slavery. It was initially abolished on February 4, 1794, during the French Revolution. However, it was reinstated in 1802, along with slavery, by Napoleon Bonaparte, who was then the First Consul. Both were definitively abolished on April 27, 1848, by the provisional government of the Second Republic. The decree, drafted by Victor Schœlcher, Undersecretary of State for the Navy, confirmed the abolition of slavery in France.

In the preamble of the text, political representatives established that “considering that slavery is an attack against human dignity […]; that it is a flagrant violation of the republican dogma: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” Article 1 stated that “slavery is completely abolished in the French colonies and possessions.” From that moment on, slaves were freed and considered citizens, often referred to as “new citizens” or “newly liberated.”