The city of Babylon, which was established along the Euphrates River in Mesopotamia, became one of the developing states in the region at that time. The city was built centuries after the Sumerians settled in Mesopotamia and established the first civilization, but by 1900 BC, it had become the capital of a small kingdom. The legendary king Hammurabi, the first great ruler of Babylon, ruled from about 1792 to 1750 BC. He expanded his kingdom to include most of the fertile land between the Euphrates and Tigris, making Babylon the center of a growing empire. For centuries, he was revered as the one who made the laws of Babylon. The Code of Hammurabi was little changed over the course of 1,000 years and remained in effect for much longer.

How Did the City of Babylon Shine?

Babylon’s splendor also aroused the interest of many invaders. The city came under Kassite rule in the 16th century which would last for about 400 years. During this period, Marduk, formerly the local god of the Babylonians, was elevated to the position of supreme god of Mesopotamia.

Babylon came under the rule of the Assyrians in the 9th century but the unrest did not subside. A series of uprisings to break free from the Assyrian yoke were suppressed and Babylon was destroyed by the Assyrian king Sinahheriba in 689 BC, and its temples were destroyed. The statue of Marduk was moved to the Assyrian capital Ninovana, and the Euphrates River’s flow was intended to be changed to drown the city and wipe Babylon from the face of the earth.

However, the period when Babylon no longer existed was short-lived. Because the city was reestablished by Sinahherba’s successor Asurahiddina. By the end of the 7th century BC, the Babylonians had regained their former power. In 626 BC, they declared their independence against the Assyrians under the influence of their new king, Nabopolassar, and 14 years later they united with the Medes, defeated the Assyrian army, and destroyed the capital city Nimova. Babylon entered its heyday with this victory against the Assyrians.

When Did Nebuchadnezzar Rule?

Nebuchadnezzar ascended the Babylonian throne in 605 BC, after the death of his father, Nabopolassar. In his 43-year reign, he re-established the Babylonian Empire and virtually rebuilt the capital, Babylon. He built temples all over his empire. Tablets bearing the name of Nebuchadnezzar are unearthed at almost every excavation site in Babylon.

King Nebuchadnezzar II used workers from all corners of his empire to complete this incredible rebuilding program. Among these were the Jews exiled from Judah when Nebuchadnezzar sacked Jerusalem in 586 BC. As described in the Torah, the Babylonian soldiers looted all the belongings of Solomon’s Temple and exiled all the people of Jerusalem, including their commanders, valiant warriors, artisans, and blacksmiths, a total of ten thousand people. No one was left except the poor people of Judah.

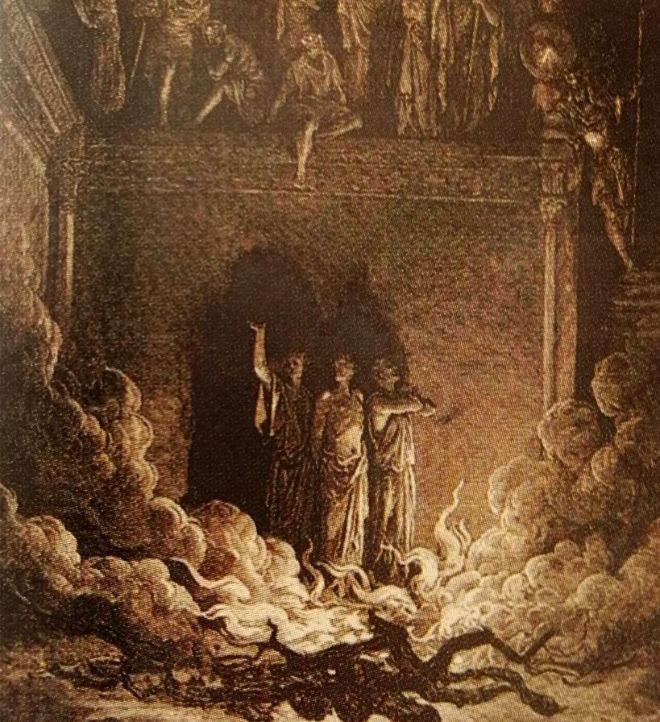

According to the Book of Daniel, it was king Nebuchadnezzar who ordered the Jewish leaders Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed Nego to be thrown into the fiery furnace for refusing to worship the golden statue. The king then went mad from God’s wrath. The Prophet Daniel says of him, “He was driven away from people and ate grass like the ox.” Contemporary scholars believe that this quote actually refers to Nebuchadnezzar’s son and successor, Nabonidus. Nabonidus was perhaps mentally ill and is known to have been away from Babylon for many years.

What Were the Codes of Hammurabi?

The Laws of Hammurabi, which were still governing Babylonian society during the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar, were written on a basalt tablet in the 1750s BC. The rules on the cuneiform tablet, which is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris, covered a wide range of aspects of social life, from how thieves should be punished to how medical problems should be treated to how children should be raised.

Under the king, society was divided into three classes: nobles, commoners, and slaves. In all three classes, men were viewed as superior to women. The punishments were based literally on the “eye for an eye” principle. The eye of someone who damaged the eye of a Babylonian noble was being removed. If a nobleman blinded a commoner, only a penalty was given.

Many crimes were punishable by the death penalty. Stealing from a burning building was punished by throwing the criminal into the fire, while those who committed adultery were tied together and thrown into the river. The hands of the children who laid a hand on their fathers were cut off. The same punishment was given to surgeons who, under their “bronze blades,” caused the death of a noble patient. When a house collapsed on the head of its owner, the builder was either killed or heavily fined.

The cost of hiring pack oxen, the wages of artisans and workers, and the wages for professional services were determined by other laws. Many Jewish laws of the period mentioned in the Old Testament bear considerable resemblance to those of Hammurabi. However, this does not mean that Moses’ laws were derived from Hammurabi, or vice versa, that Hammurabi was influenced by the Prophet Moses. It is more likely that similar social conditions under similar climatic and economic conditions led to more or less the same legal decisions.

What Did the Babylonians Believe?

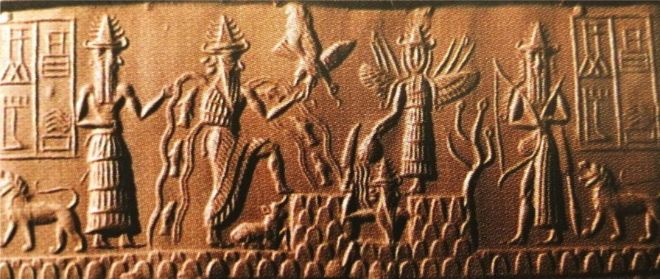

As with the ancient Greeks and Romans, the peoples of the Middle East had a number of common deities. The Sumerians, Assyrians, and Babylonians worshipped three main gods: Anu, the king of the gods; Bel, the storm god; and Enki, or Ea, the god of wisdom and magic. Sometime in the second millennium B.C., the Babylonians elevated Marduk, or Bel, to the top of the gods. He was the son of Enki and one of the second-period gods. A statue of Marduk was located in the Esagila Temple. The entrance to the temple was guarded by winged creatures known as kurub.

Sacred marriages between Babylonian kings and the goddess Ishtar were also celebrated in Esagila to ensure the fertility of their country and the longevity of the kings. At the top of the ziggurat, beside the temple, was the altar where Marduk descended to visit his people. On holy days, the people watched in awe as the king and priests climbed to the top of the steps to greet the god.

Ishtar, whom people can observe in the sky as the planet Venus, was the goddess of love and war. Herodotus describes the “shameful tradition” that every Babylonian woman had to go to the temple of Ishtar once in her life and have sex with a stranger there. Some ugly women also say that they had to wait in the temple for four years until a man chose them. It is also said that the Babylonians were very cautious about the prophecies. For instance, if a dog raised its leg at a man, it would predict disaster for that man, and he would have to make a clay figurine of the animal and throw it into the river to fend it off. Meanwhile, he had to repeat some magical words. After the work was done, the man had to go to the tavern.