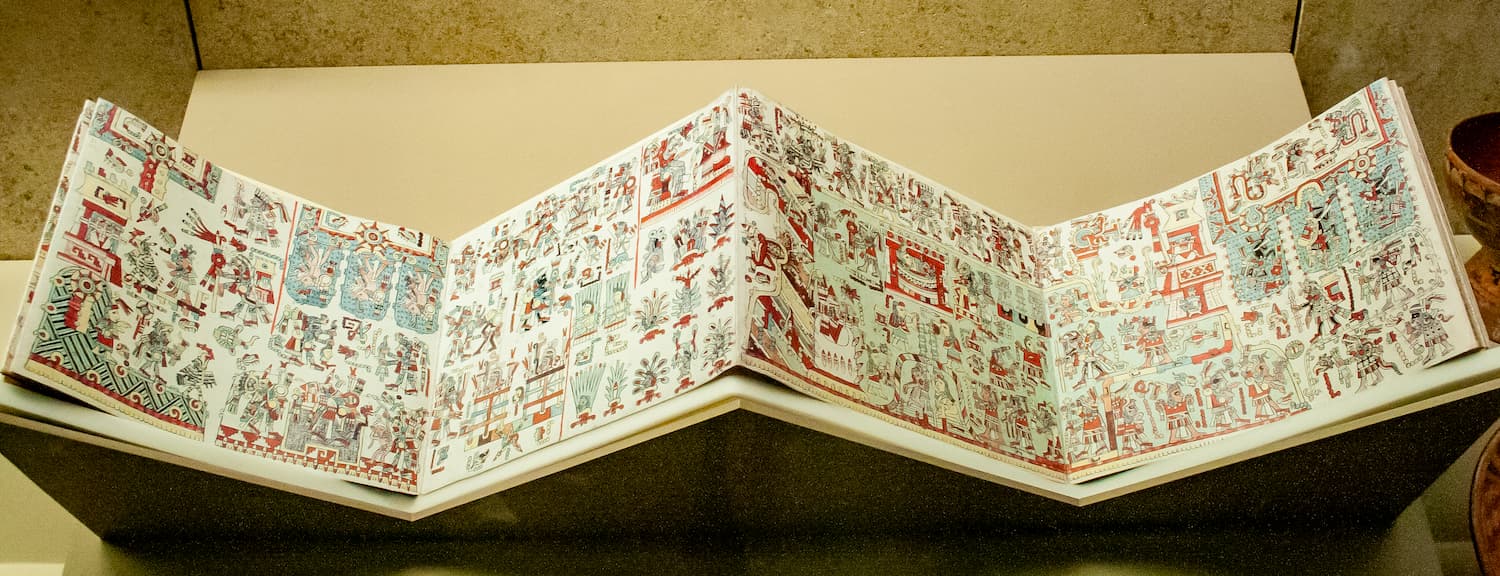

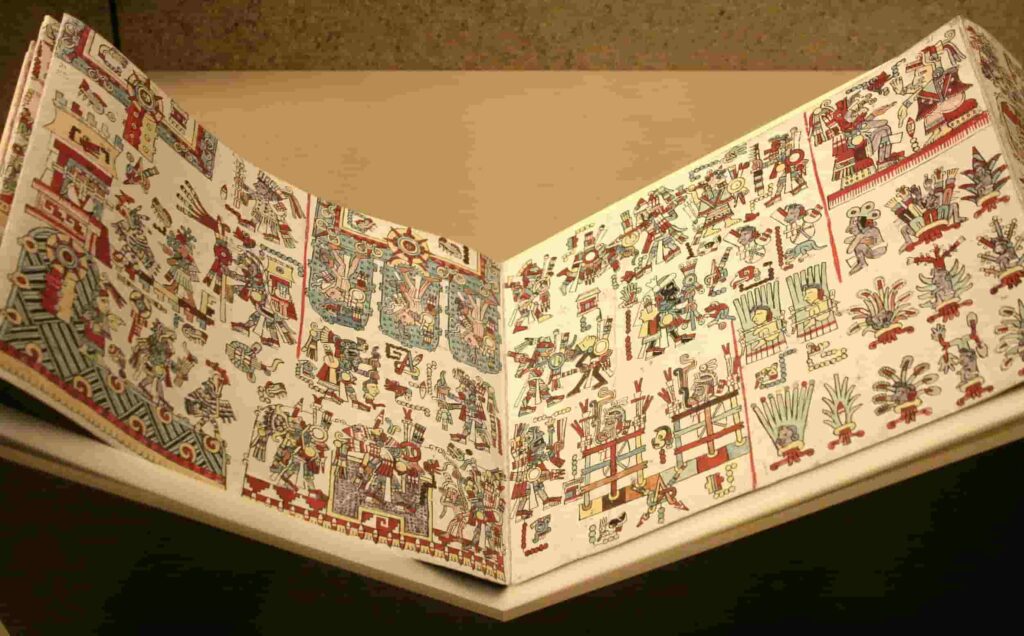

The Nuttall Codex (also known as Tonindeye or Zouche-Nuttall Codex) is a pre-Hispanic pictorial manuscript belonging to the Mixtec culture. It has two sides: side 1, which records the life, conquests, and alliances of Ocho Venado, a prominent Mixtec ruler, and side 2, which deals with the origin of the dynasty and the history of Tilantongo and Teozacoalco. The Zouche-Nuttall codex is one of the six Mixtec codices considered to have pre-Hispanic tradition that survived the conquest of Mexico.

The manuscript consists of 16 pieces of treated deer skin joined at the ends, forming a long strip of 11.41 meters. The sheets are folds made in each of the pieces of skin, resulting in a total of 47 sheets, not all of which are painted. The actual date of the codex’s creation is unknown, but it is estimated to be around the 14th century in the town of Tilantongo. Side 2 may be more recent than side 1, possibly created in Teozacoalco in the early 15th century.

There is no information on how the codex left Mexico. It was likely sent to Spain in the 16th century, shortly after the conquest of the Mixtec people in 1522. It was first identified in 1854 in the Dominican convent of San Marcos in Florence. Five years later, it was sold to John Temple Leader, who sent it to Robert Curzon, the fourth Baron Zouche. A facsimile edition was published by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University in 1902, with an introduction written by Zelia Nuttall. Today, the codex belongs to the collection of the British Museum.

Name

The British Museum, the current owner of the manuscript, classifies it under the compound name Zouche-Nuttall. The codex received this name from Robert Curzon, the fourth Baron Zouche, and Zelia Nuttall, key figures in its history.

Characteristics

The Zouche-Nuttall codex is an extensive book, folded like a screen and illustrated in color on both sides. It is composed of 16 strips of treated deer skin joined at the ends. When complete, the codex is a long strip measuring 11.41 meters; its sheets or plates are the result of folds and creases in the same strip of skin. Each sheet has an approximate measurement of 24.3 cm in width by 18.4 cm in height. The codex has a total of 94 sheets; 47 on each side. 42 of the 47 sheets were painted on the obverse (side 2), and 44 sheets were painted on the reverse (side 1).

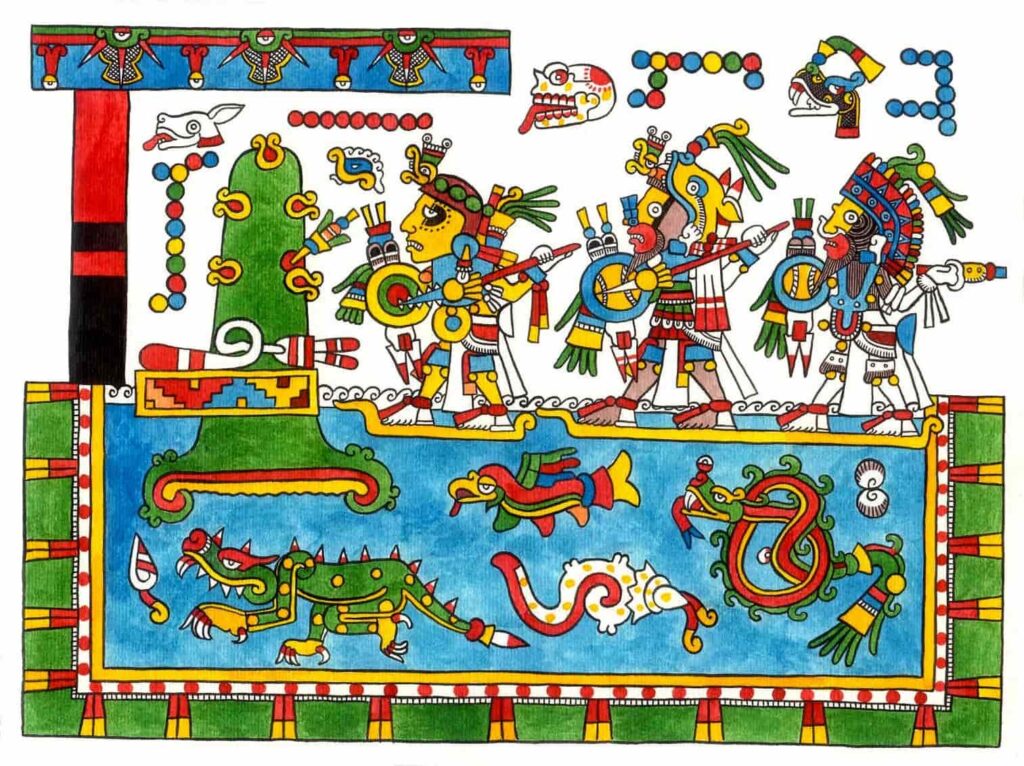

The surface of each sheet is covered with a white base of stucco and plaster, applied before the colors. This white cover was also used for corrections on the already drawn designs. Natural dyes of red, yellow, blue, purple, brown, ochre, and black were used on both sides of the codex.

History

The way in which the Nuttall codex left Mexico is not known, but it is known to have been in the Dominican monastery of San Marcos in Florence, Italy, in 1845. In 1859, the codex was acquired by the prominent English politician John Temple Leader, who also resided in Florence. He bought the document from the monastery to send it to his friend Robert Curzon, who would become the fourteenth Baron Zouche. Curzon lived in England and had a magnificent collection of antiquities. Curzon died in 1873, and the collection was inherited by his son, who, facing a series of difficulties, deposited his father’s collection at the British Museum in London in 1876.

The researcher Zelia Nuttall obtained permission to investigate it in 1902. The first facsimile edition of the codex was published under the auspices of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

However, the publication consisted of drawings made by an anonymous artist. It was the Peabody Museum that named the Mixtec codex Nuttall in honor of the researcher.

The British Museum acquired the codex in 1912 and gained definitive possession of it in 1917 upon the death of the last possessor of the collection. It is registered under the signature Add.

MS 39671.

Review

The Nuttall codex was identified as belonging to the Mixtec area by the researcher Alfonso Caso, dismissing the belief that it was a Zapotec document or from central Mexico. It is difficult to pinpoint the exact place of origin of this codex; it is believed it may have been made in the lordship of Teozacoalco, as the obverse includes a genealogical relationship of the rulers of Teozacoalco and Zaachila. However, other researchers believe it is two different documents (obverse and reverse) made at different times and places for very different reasons.

Side one emphasizes conquests, alliances, political meetings, and acts of obedience and recognition to Ocho Venado more than other codices. Moreover, the place most represented on this side of the Nuttall is Tilantongo, to the extent that the enthronement date of 8 Venado in the coastal lordship of Tututepec, among other events, is ignored. The emphasis on Tilantongo suggests it as the possible place of origin of the great conqueror’s biography. The exact date of the creation of side 1 of the Nuttall codex is unknown, but the events it records can be placed between the 11th and 12th centuries. Probably, the codex’s production responded to a legitimation by the descendants of 8 Venado around the 14th century when the Tilantongo branch began to fade. Several years later, the lordships of Tilantongo and Tezoacoalco were unified by Lord 9, so perhaps the codex changed residence to Tezoacoalco, where the second part of this codex would be painted.

Featured Image: codex | British Museum