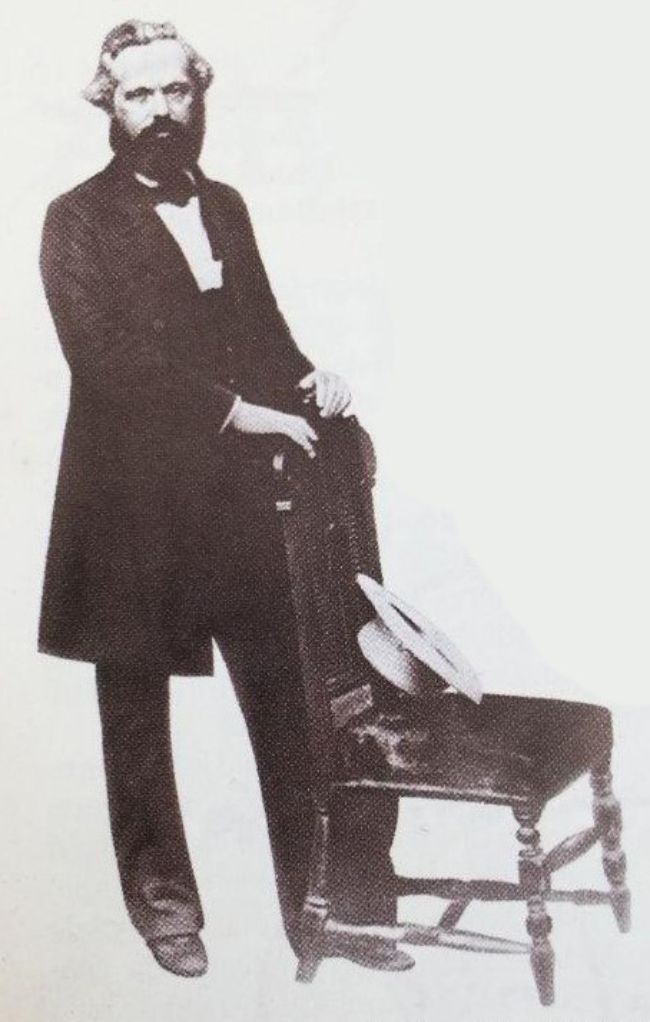

Let’s talk about the Communist Manifesto and the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe. German journalist and economist Karl Marx was the leader of the Communist League in 1847. The league was established a while ago and was about to hold its first meeting. Delegates chose London for this event. Secret talks continued between November and December. With the participation of the radical working-class Chartists who demanded reform in Parliament, the population of the league reached 100. The biggest delegation in the party belonged to German tailors. Leader Karl Marx wrote down the principles of the Communist League at the end of the meeting. The Communist Manifesto was published three months later.

Karl Marx’s acquaintance with capitalism

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.

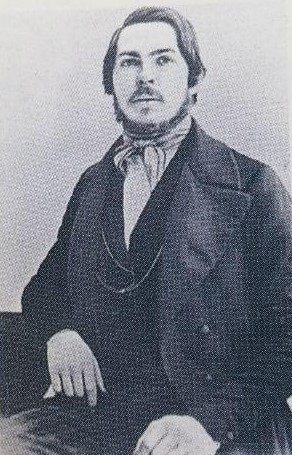

Karl Marx was invited to England first, in 1845. The invitation was made by Friedrich Engels, who offered Marx the chance to work on the book called The German Ideology. A little younger than Marx, 27-year-old Engels introduced him to the cotton fabric industry in England. The industry was capitalist.

Engels’ father was an industrialist and he was running the Manchester branch of his family business in Germany. Karl Marx saw the superiority of the capitalist order over feudalism in England and concluded that “All human history is the history of class struggle.” Marx thought that the capitalists (the bourgeoisie) and the working class (the proletariat) were headed for a big fight.

England’s capitalist factories were established in the North. Karl Marx called these “dark satanic mills.” Because he witnessed that the workers in the factories were working unhealthy jobs in the dirt for long hours and living in congested shacks. All this was to maximize the profitability of rich fabric merchants.

Britain was the model country of capitalism at the time because it was the first industrial state. The cotton fabric industry was largely dependent on factory production. Seeing that the poor workers’ labor was exploited to enrich the bourgeoisie class, Marx predicted that the working class would initiate an uprising, and this revolution would result in victory.

“Revolution” was then a popular term in Europe. There were leaders such as the King of France, Louis Philippe, and the Prince of Australia, Metternich, who saw that the new order established with the defeat of Napoleon and with the end of the “revolutionary wars” could now be destroyed. Karl Marx decided to hold an international meeting of the Communist League because of the “Panic of 1847” and the failure of British banks.

Capital is dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.

The Communist Manifesto and the birth of Marxism

The Communist Party Manifesto, known as the joint work of Marx and Engels, was actually solely Marx’s work, and Engels contributed only a letter. Still, thoughtfully, Marx added Engels’ name to the cover next to his name. The Manifesto was written in Brussels between December and January. The Communist Manifesto then moved to England and was given to a German printer in Bishopsgate, London. The printer printed the 23-page manifesto in German. The Manifesto was translated into Swedish in 1848 and into English in 1850. Its Russian version was only to be released in 1869.

Despite its 12,000 words, the Communist Manifesto was notable for its simplicity. Because if it was a long and complex philosophical text, that would make it impossible to reach out to the working class. Marxism was born, and for many, its concise and witty language was as impressive as the holy texts. The Communist Manifesto is remembered most with its opening phrase, “A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism,” and the part that addresses the workers: “Proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains: they have a world to win: workingmen of all countries, unite!“

According to Karl Marx, the laws of advanced industry and capitalist production would succumb to the revolution of the proletariat. The collapse of the established state order and the bloody birth of a classless society would be the Marxist version of the New Jerusalem: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” However, the rhetoric was underestimated during that period. Only a few socialist groups cared about the message. They only produced some revolutionary conspiracies.

The disbanding of the Communist League

By 1848, various revolutions began to arise in the nation-states of all of Europe. However, these revolutions had nothing to do with socialism. The revolutions of 1848 were suppressed a year later, and the ruling class regained its former strength. Five years after the secret meeting in London, the Communist League disbanded. The radical manifesto seemed to have failed, but Karl Marx’s words would radically change the course of history in both Europe and Russia in the 20th century.

Karl Marx and Das Kapital

Before we can talk about the 1848 revolutions in Europe, we need to talk about Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Karl Marx was born in Germany in 1818; Engels was born in 1820. These two thinkers gained radical political views in different ways. Engels never got a university education, and he joined his family’s textile business after his military service. Marx studied law and philosophy at the university and spent his life in the world of books.

Karl Marx experienced his sole political experience in Cologne, where he stayed briefly during the revolution in Germany in 1849. Marx, accused of treason, left the continent and spent the rest of his life working at the British Museum almost every day; he wrote many significant books on economy and politics one after another in England. He was living in poverty and struggling with chronic diseases. After 1850, he decided to focus on his research for Das Kapital, his three-volume work that looked at modern society.

After joining the 1848 Revolution in Baden, Engels returned to England. He became rich through the cotton fabric trade and entered the Cheshire Hunting Group of the elite. He lived with a girl named Mary Burns, an Irish worker, and after her death, he married her sister Lizzie. Engels was almost Marx’s only support in the final years of his life (from 1870 to 1883) and also assisted him in writing his works.

The first volume of Das Kapital, Marx’s critique of capitalism, was published in Hamburg in 1867. After the death of Karl Marx, his comrade Engels used the notes left by him and completed his work.

Dialectical Theory

When Marx was a student at the universities of Bonn, and Berlin in the late 1830s, German intellectual circles were under the influence of Georg Friedrich Hegel’s philosophy. Hegel explained the change and movement in the world, in other words, the basic historical process, based on a simple formula called “dialectic.” According to Hegel, every principle, idea, or “thesis” produces the idea that is a reaction against it, that is, an “antithesis.” From the clash of these two ideas, a new idea emerged over time. This was called “synthesis,” and, as a new idea, it again produces its own antithesis and synthesis, and thus the cycle continues forever.

Marx adapted Hegel’s system by removing it from the world of ideas and placing it in the material world. Therefore, his system is known as dialectical materialism. Marx’s ideas had a remarkable appeal. Marx’s detailed work at the British Museum on the growth of British industry is said to be the source of this idea.

The Revolutions of 1848

In the previous period, the bourgeoisie class, consisting of capitalist merchants and producers, opposed the system of economic feudalism dominated by landlord nobility. The conflict that happened in the British Revolution of the 16th century and the French Revolution of the 17th century resulted in the victory of the capitalist bourgeoisie and the Industrial Revolution.

With the current administration, the bourgeoisie could deprive workers of excess capital and profit. According to the dialectic, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie now had to struggle. While European countries were industrializing in the middle of the 19th century, the proletariat grew bigger as well.

The biggest difference in Marx’s materialist dialectic was the belief that the inevitable victory of the proletariat would significantly change history. Because, with socialism or communism, the states of the age would be destroyed and a perfect society could be created: this envisaged a utopia where all conflicts would end. So the Earth could turn into a paradise.

Who were the Chartists?

The 1832 Reform Act was the starting point of modern British democracy. For the first time, many middle-class men gained the right to vote. With some exceptions: working-class men still lacked the right to vote. One of the results of this was the working-class movement that aimed to gain political rights for the workers. This movement took its name from the People’s Charter (a public statement), which was written and published in 1838 at the meeting of the London Workers Union.

The Chartist movement got stronger in the following years and gained supporters with two major protest campaigns. These were the “Ten-Hour Movement” (calls were made to work only for up to 10 hours a day at new textile factories in the north) and the opposition to the Poor Law Act (demanding the abolition of the new Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834).

With this law, large working houses were built, and unemployed people were forced to live there. The unemployment created by this economic bottleneck became apparent in business life and in the trade cycle of 1836. This unemployment was much larger than the new Poor Law Amendment Act could ever cope with. In a few years, job opportunities decreased so much that Britain was dragged into the worst economic crisis after the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

Despite its economic foundations, the Charter was limited only by political demands:

- Universal voting rights for men

- Equalization of election districts

- Voting with a closed envelope

- Abolition of the condition to own a property to enter Parliament

- Payments to the members of parliament

- Election of members of parliament every year

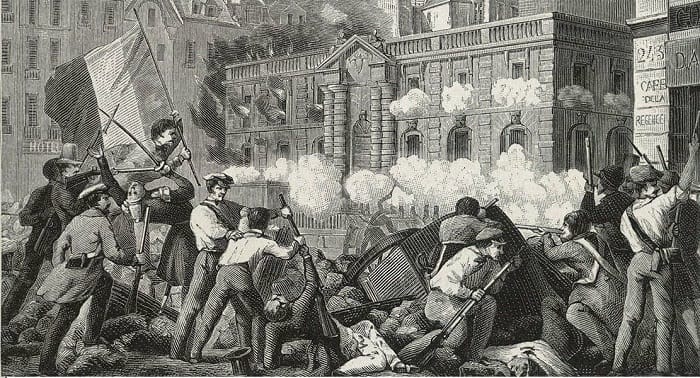

Why did the 1848 revolutions fail?

“When Paris sneezes, Europe catches a cold,” said Prince Metternich. Metternich ruled the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1809 until the 1848 Revolutions, when he lost power. He drew attention to the critical situation in Europe in 1848 with this famous quote. This was the French uprising. The first uprising started in Milan in January but resulted in the dethroning of King Louis Philippe in February. This event sparked a major fire in Europe and resulted in a major event called the Revolutions of 1848.

The causes of the revolutions of 1848 varied from country to country. Food prices rising due to poor harvests and potatoes being destroyed; a typhus outbreak; the return of cholera; and general unemployment caused by the collapse of credit institutions and bankruptcies were among the reasons for the 1848 revolutions. All these factors turned the lives of the poor who lived in European cities into misery. That’s why riots broke out in Milan, Paris, Frankfurt, Vienna, Budapest, and Warsaw.

However, it was not clear what the 1848 revolutions targeted. Nationalism was not widespread yet. Germany and Italy remained fragmented; the Austria-Hungary Empire continued to retain control of the nations in Italy and the Balkans. One of the common goals of the 1848 revolutions was the demand for state administration to be based on constitutional foundations. This concluded positively only in countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium.

The monarchy, which was re-established in France in 1815, was abolished again. Britain, which had the most advanced economy, was one of the few European countries that did not experience any revolutions. Another was Russia, whose economy was at its lowest level.

As Karl Marx predicted in The Communist Manifesto, the revolution of 1848 was not fired by the proletariat but especially by the intellectuals living in the capital cities. While the peasants, who make up the vast majority of the European population, stayed away from the revolutions, the working class, or the bloodiest group, was lacking a leader. “In the final analysis,” writes Engels in sadness, “the fruits of the revolution were reaped by the capitalist class.“