The Crown of Charlemagne is a crown worn by French kings upon their coronation. Many French kings simply named their imperial crowns the “Crown of Charlemagne,” just like Napoleon Bonaparte did in 1804. When the king’s crown was destroyed for some reason, the queen’s crown would be used in royal ceremonies, including the coronation of the new king. And there were two pretty similar crowns of Charlemagne, which were formerly part of the regalia of the French monarchy but were lost when the first one was melted by the Leaguers in 1590, and the second Crown of Charlemagne was destroyed during the French Revolution in 1793. Before that, it remained in use until the coronation of King Louis XIV in 1775, and the Treasury of Saint-Denis subsequently received it as a donation.

History of the Crown of Charlemagne

The Origin of the Crowns and Their Gemstones

Among the Ancien Régime regalia, the Sword of Charlemagne, Joyeuse, also survived to this day. There is no written evidence that would allow us to pinpoint when the first Crown of Charlemagne was made or even whether both crowns were a matched set or just two comparable pieces, of which one would have been a later replica.

According to one theory, the origin of the Crown of Charlemagne lies with Charles the Bald (d. 877 AD), Charlemagne’s grandson. A simple circlet of four curving rectangular jeweled plates was crafted for the king in the 9th century.

Given the significance of the gemstones and their quantity, Bernard Morel claimed that the crowns could not be produced until Philip II of France returned from the Third Crusade (1189–1192). In fact, at the time, stones of this size were very unusual in Europe and could only be obtained from the East.

Therefore, the French king could not have had two crowns so lavish in gems, particularly valuable stones of various sorts, fashioned before the Third Crusade on the Levant (See also: Crusades).

The Crown of Charlemagne Over Time

Crowns worn during the coronations of Philip II of France and his Danish bride Ingeborg are almost indistinguishable from one another and have been variously referred to as the Crown of Charlemagne (or sometimes as the Crown of Saint Louis):

The second marriage of King Philip II of France to Ingeborg of Denmark took place on August 14, 1193. It was a holy day the day after, so the king put on the Crown of Charlemagne. In 1223, Philip II left his and the queen’s crowns to the Treasury of Saint-Denis through a will, which also included the Sword of Charlemagne at the time.

The two crowns were later presented to Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile shortly after their coronation at Reims in 1223. Instead of honoring his father’s request, the king chose to pay the monks a substantial quantity of money in exchange for the return of the two crowns.

The Restoration of the Crowns

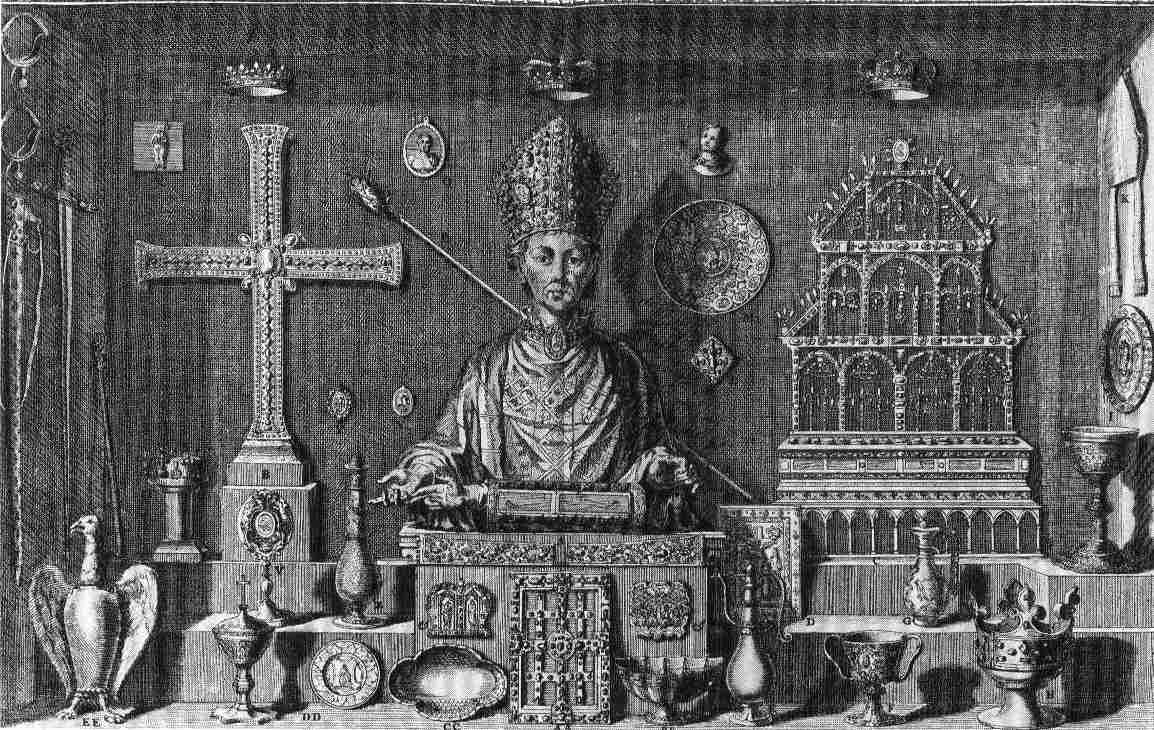

The reign of Louis IX began in 1226. In 1261, he chose to permanently restore the two crowns to the Abbey of Saint-Denis, with a scroll explaining that they were created for the coronation of kings and queens and are displayed above the morning altar during solemn feast days.

This is how the crowns of both the king and queen became part of the church’s collection. All kings and queens up to Henry III of France (d. 1589) were crowned with the Crown of Charlemagne. The only exceptions were John II (d. 1364), who had himself crowned with the holy crown, and Charles VII (d. 1461), who did not have the treasury when Joan of Arc took him to Reims.

The Catholic League (1576) was funded in part by the dukes of Mayenne and Nemours, who in 1590 seized the throne and established it in their names. As time went on, the almost identical crown owned by the queen was used during coronations. Those two crowns were successively dubbed the “Crown of Charlemagne”.

Originally crafted for the Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great’s coronation in 962 at the imperial monastery of Reichenau, the Reichskrone was later recognized as the Crown of Charlemagne and featured prominently on the escutcheon of the Holy Roman Empire‘s Arch-Treasurer and atop the coat of arms of the Habsburg emperors, as seen in the Hofburg Palace in Vienna.

The Design of the Crown of Charlemagne

The exact description of the crowns of Charlemagne was recorded in an inventory conducted in 1534 by the treasury. The inventory noted in Latin that there was a striking similarity between two crowns.

Circlets

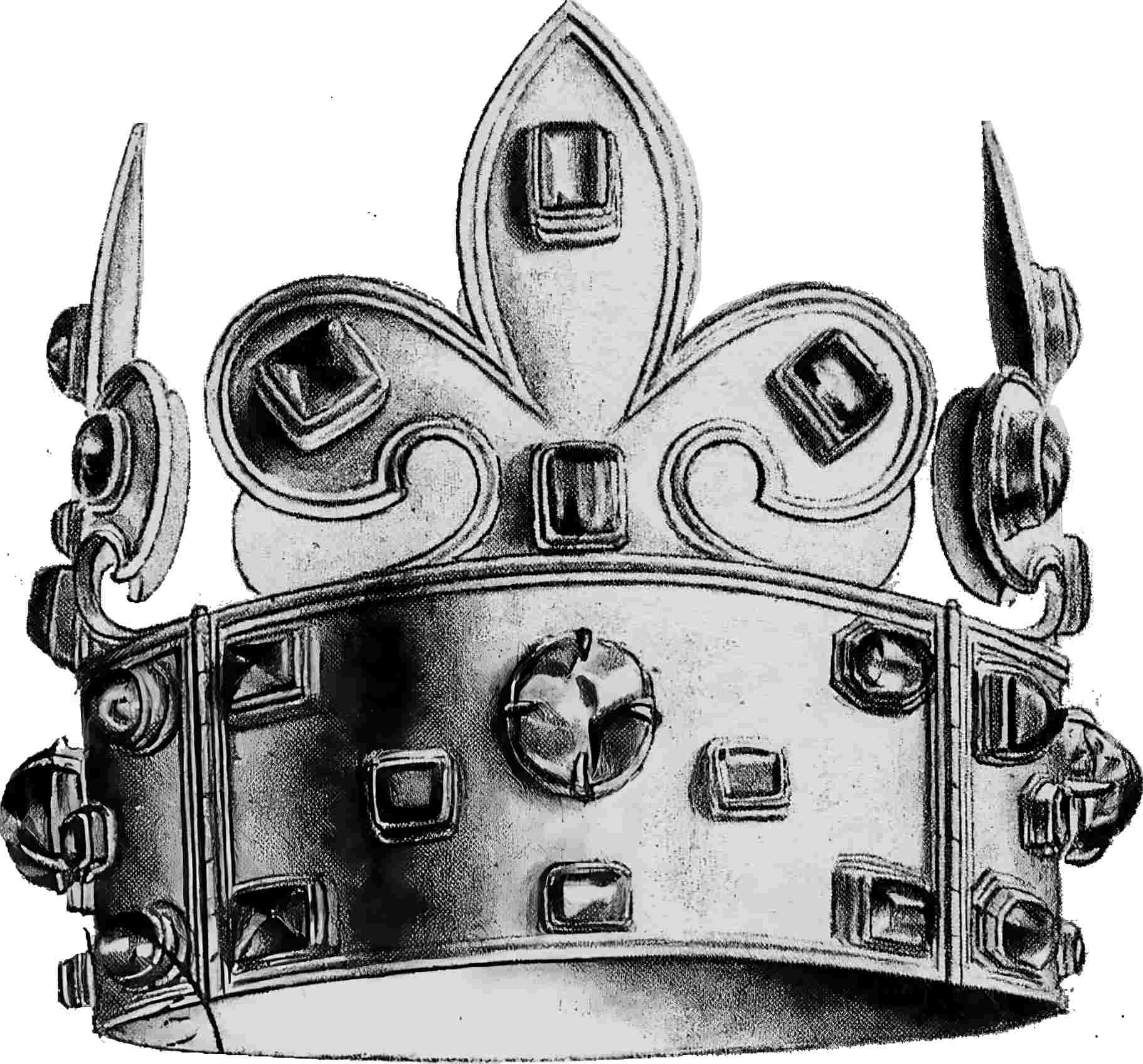

Both crowns of Charlemagne were made of pure gold, with the king’s weighing approximately 9 lb (4 kg) with all the stones of the cap and the silver chains. They were made up of a wide band and four rectangular plates joined together at the base by systems of hinges to form the base circle.

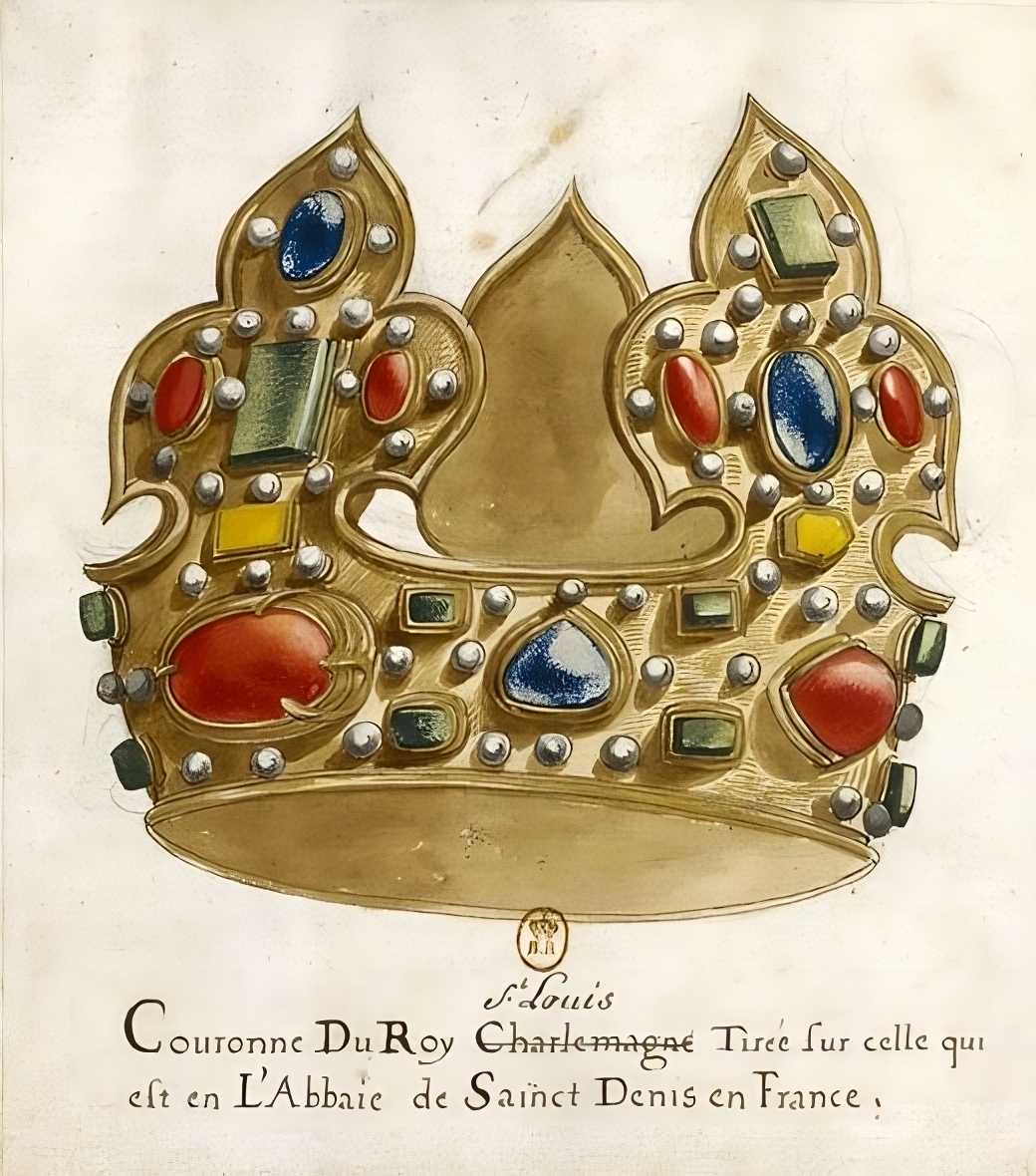

The engraving of the crown by Dom Michel Félibien and a watercolor painting by Montfaucon allow us to determine that each of these four rectangular plates had a huge and exquisite fleur-de-lis at their center, the decorative symbol of French heraldry.

The circlet and the fleurons comprised a total of 48 gemstones, distributed as 16 balas rubies (spinel), 16 emeralds, and 16 sapphires. Each element (a plate and a fleuron) was decorated in the same way.

Three rubies framed the emerald-studded base of the fleur-de-lis. Each rectangular plate has four sapphires at its corners, a ruby in the middle, two emeralds on each side, and a third emerald positioned below.

The two crowns of Charlemagne looked almost similar, with the exception that the queen’s was somewhat smaller, lighter, and adorned with smaller, less uniform jewels.

Cap

A 200-carat ruby and 112 pearls decorated the crown’s conical inner headpiece, which belonged to the king. King John II (d. 1364) ordered this regal velvet headgear, which had a crimson tint.

The ruby was placed on a square pillar, and the headpiece had 12 strands of 9 rosette beads. The pillar’s collar was fastened to the cap using four gold bands and four more pearls, making a cross. Around the pillar’s base is an inscription in Latin that honors the benefactor of the crown.

Henry II had the satin-lined velvet cap of the Crown of Charlemagne recreated in 1547.

References

- Medieval Art: Treasures of Saint Denis:Crown of Queen Jeanne d’Evreux – Pitt.edu

- The History of Charlemagne – George Payne Rainsford James, 1833 – Google Books

- Charlemagne – Father of a Continent – Alessandro Barbero, 2004 – Google Books