What was daily life like in ancient Rome? How did people spend their days in the Roman Empire? The Roman civilization was an unusual culture with some resemblance to our own. There are parts of life for the residents of the ancient Roman Republic in the 1st century BC that are somewhat comparable to modern living and others that are entirely foreign to our ears. The Romans were known for their daily routine of going to work, indulging in takeaway meals, and later enjoying summer festivals while savoring a bottle of wine. The Romans saw having sex with prostitutes in the temple as a holy act and burning animals as a means to curse their enemies.

- The Earliest Fire Brigade in Ancient Rome

- The Right to Vote in Ancient Rome

- Patronage: A System of Favoritism

- Family, Ancestry, and Women’s Rights

- Education in Ancient Rome

- Slavery in Ancient Rome

- The Daily Life of Ancient Roman People

- Festivities and Worshipping in Ancient Rome

- Leisure Activities in Ancient Rome

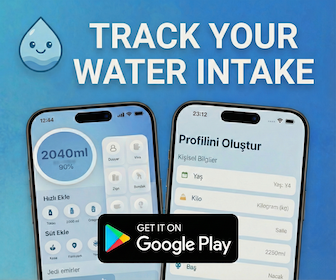

The Earliest Fire Brigade in Ancient Rome

We now take it as a given that if there is a fire, the fire brigade will arrive to put it out. Fire was a major concern in ancient Rome because of the high concentration of wooden structures. For a long time, there was no fire brigade in Rome. If a fire broke out, people had to wait for citizens or soldiers to arrive and put it out.

However, starting about the year 70 BC, fire crews were dispatched to the scene whenever a fire was reported. But this fire brigade wasn’t created for the greater good of society: Marcus Licinius Crassus, the wealthiest man in Rome and a supporter of Julius Caesar, had his own private fire brigade.

Crassus would go down in history as an immoral businessman:

Upon arrival at the fire scene, the fire extinguisher crew made an unexpected declaration: “We have the capability to extinguish the fire, but Crassus will only do so if he acquires this building.”

Naturally, they were eager to make a trade. If they refused to sell, the fire brigade would wait until an adjacent structure caught fire before beginning negotiations.

This filthy fire brigade marked the inception of the world’s very first organized firefighting unit.

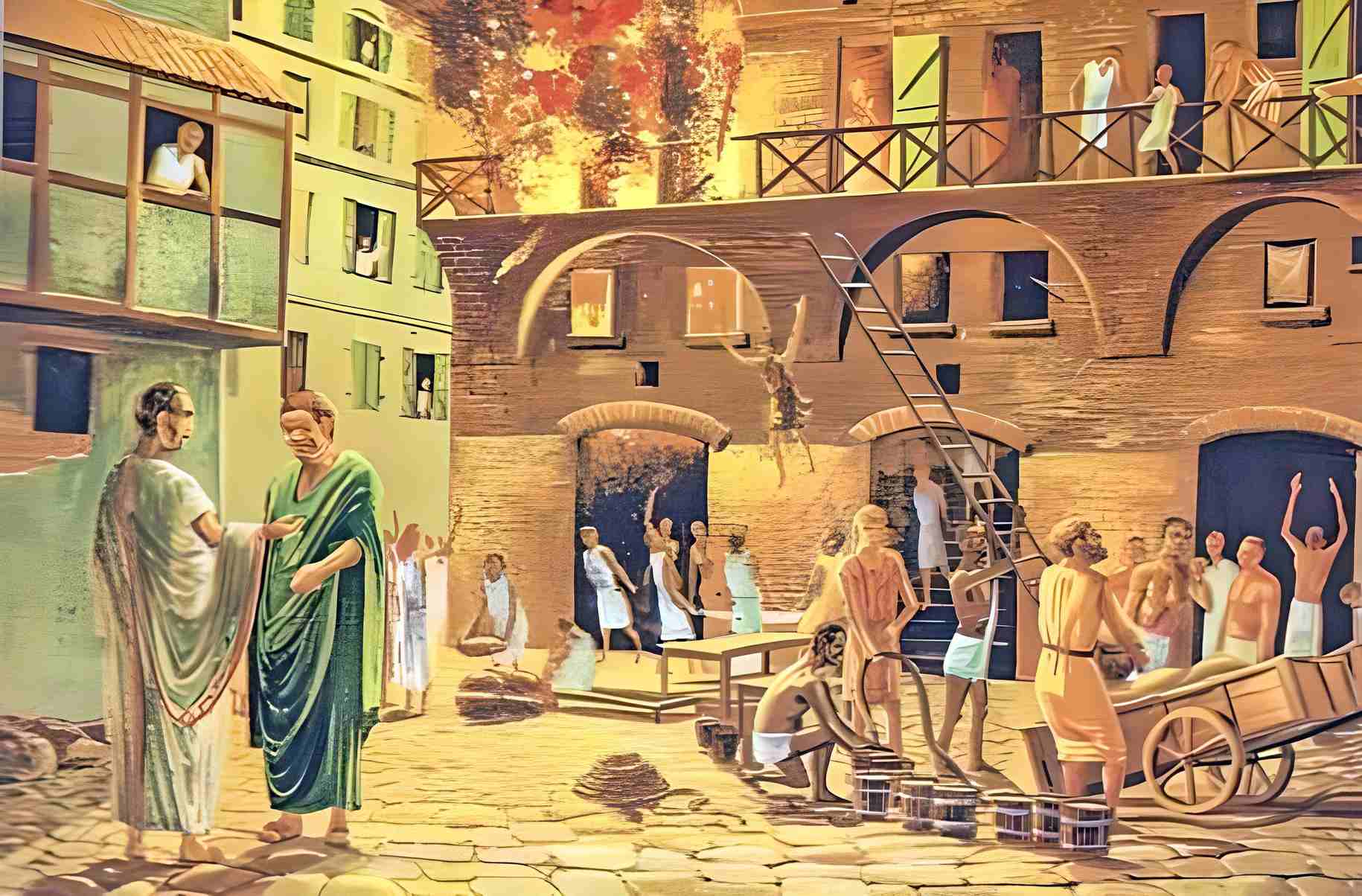

The Right to Vote in Ancient Rome

As a republic, Rome granted the right to vote to all free males who met the age requirement. Today, this creates the false impression of a somewhat democratic administration; however, it was not true.

The Roman government’s bureaucrats were elected, but not with a majority vote. Citizens first elected a Centuriate Assembly, made up of 373 representatives (called centuries), who could vote for top government leaders.

In these gatherings, everyone had the right to vote, but the representation was quite uneven.

There were 35 distinct Roman tribes, and each tribe was further subdivided into five “classes.” The term “tribe” implied a hereditary tie, but in reality, people were grouped together based on where they resided. Therefore, “class” was the most significant.

In the daily life of Rome, there was a significant demographic disparity between the wealthiest and lowest strata, with the “propertyless” plebians (commoners) comprising more than 70% of the total.

The voting started with the electors from the highest class and proceeded until a majority of votes were cast, thereby preventing the common electors from voting. For this reason, the richest men, the top 0.1 percent or so, had a disproportionate influence in the so-called “republican government” of ancient Rome.

There was also a law-making body called the Concilium Plebis (Plebeian Council), and an existing entity called the Senate that determined how the legislation should be applied. But the common Roman people lacked a say even in these official institutions.

This meant that the vast majority of Romans could not influence the government at all. Even if they technically possessed the “right to vote,” it was mostly symbolic.

Given the widespread unhappiness with the political system as a result of this structure, it was inevitable that certain politicians would resort to violence in an effort to subdue the opposition (such as the Brutus and Cassius brothers who conspired against Caesar).

Patronage: A System of Favoritism

The Roman political system and society relied heavily on patronage. It was highly valued in Roman society to show allegiance to someone who had helped you out.

As a result, there was an established norm wherein people who had significant resources and voting power would negotiate deals with politicians in return for financial gain and special interests. Bribery was an accepted part of politics in the daily life of the ancient Roman Republic.

This master was called a “patron,” and the person who served was called a “client.”

The level of special treatment a client received correlated directly with their prominence and power. But even commoners were considered clients if they could offer any form of assistance.

Having a vast number of ordinary people as clients and a means to organize them allowed politicians like Julius Caesar to quickly create a violent mob when required.

In this system, patrons were greeted early in the morning by a line of people waiting at their doors. These individuals would exchange greetings, make requests, and later respond to the patrons’ calls for assistance.

It was intriguing to observe that some individuals chose to make a living solely by participating in this greeting ritual and welcoming members of important families every morning, rather than engaging in traditional business or labor. Meanwhile, others managed to sustain their livelihoods by establishing strong relationships with influential patrons.

This intricate web of patronage created a unique dynamic where social connections and favors held significant value in the daily life of ancient Roman society.

This system of patronage has been passed down as a tradition in Sicily among the Mafia: In the opening scene of the 1972 film “The Godfather,” we see members of the Mafia pay a visit to the Mafia don (boss) to say hello and beg for a favor.

Family, Ancestry, and Women’s Rights

Pater familias (the father of a household) was the Roman family system that enforced stringent gender inequality and regulated the daily lives of Roman residents. In Roman law, the eldest male member of the family had almost full control, including the ability to murder family members who defied him. Different customs and laws, however, limited his influence, and it was uncommon to be “murdered legally” in ancient Rome.

Although there were exceptional women who wielded political power (such as Cornelia, mother of the Gracchus brothers in the Late Republic, c. 146 BC–31 BC), Roman women were denied the ability to vote and could not occupy official government offices. However, some Roman women still gained financial freedom when they were granted the right to possess property in their own names, sign contracts, and file criminal charges.

Males carried the torch in the daily life of the Roman family. However, it was normal practice for Roman women to keep their registration with their parents’ household even after marriage.

The divorce process in the ancient Roman Empire was simple for all parties involved. A divorce was granted after the wife merely left the marital home and declared her intent to no longer live with her husband.

The father often took custody of the kids, while the mother maintained her own property after the divorce since her assets were held in a different name throughout the marriage. This system did not require alimony.

In the Late Roman Republic (c. 146 BC–31 BC), divorce was not bound by specific reasons or seen as a social taboo; rather, it was regarded as a natural occurrence.

Education in Ancient Rome

There were no public schools in ancient Rome, so pupils who were fortunate enough to find a teacher often had more than a dozen classmates in their small class.

However, the vast majority of Roman children were not educated. It is believed that fewer than 20% of ancient Roman adult males and 5% of ancient Roman females could read and write.

As a result, only a select few children from affluent households were able to attend school in the daily life of ancient Rome.

After mastering the fundamentals of reading, writing, and arithmetic, students moved on to study the Greek language, as well as Greek poetry, literature, history, philosophy, and oratory.

Slaves were mostly responsible for the upbringing of Roman children.

Slavery in Ancient Rome

During the Roman Republic, slaves were crucial to the economy and the daily life of society. There were several types of Roman teachers, farmers, bakers, housekeepers, nannies, craft workers, and slaves. Slaves made up the vast bulk of Rome’s prostitute population.

There were Roman, Greek, German, and African slaves, among many others. Slavery in Rome was not founded on “racism” in the same way that it is in the history of the United States.

Those who defaulted on their debts were sold into slavery, and the cycle continued. Educated Greek slaves were in great demand and sometimes sold for exorbitant sums to serve as private tutors to the affluent.

However, captured people who were defeated in a war were by far the most prevalent kind. In his Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), Julius Caesar is said to have attacked a city in what is now France and sold all 52,000 of its residents on the spot to slave dealers.

Rome amassed a significant slave population during her swift conquest of the Mediterranean from the 2nd to the 1st centuries BC. By the end of the 1st century BC, it was believed that around 20% of the whole population of Rome and 40% of the Italian population were made up of slaves.

In ancient Rome, several percent of miners died annually from sickness, overwork, or accidents, making this occupation essentially a death sentence.

On the other hand, secretaries of high-ranking government officials often enjoyed a lavish lifestyle and considerable independence if they could read, write, and think critically.

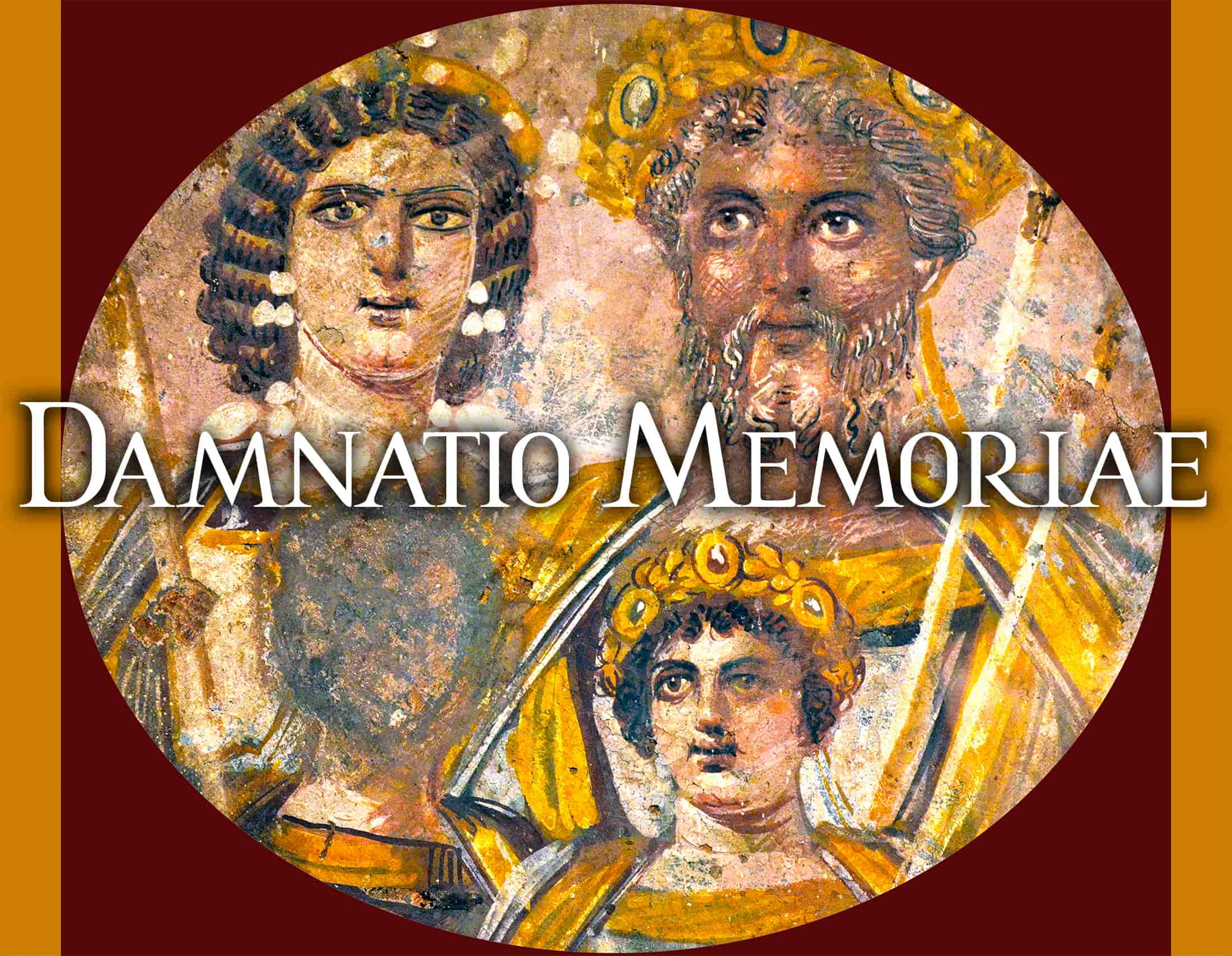

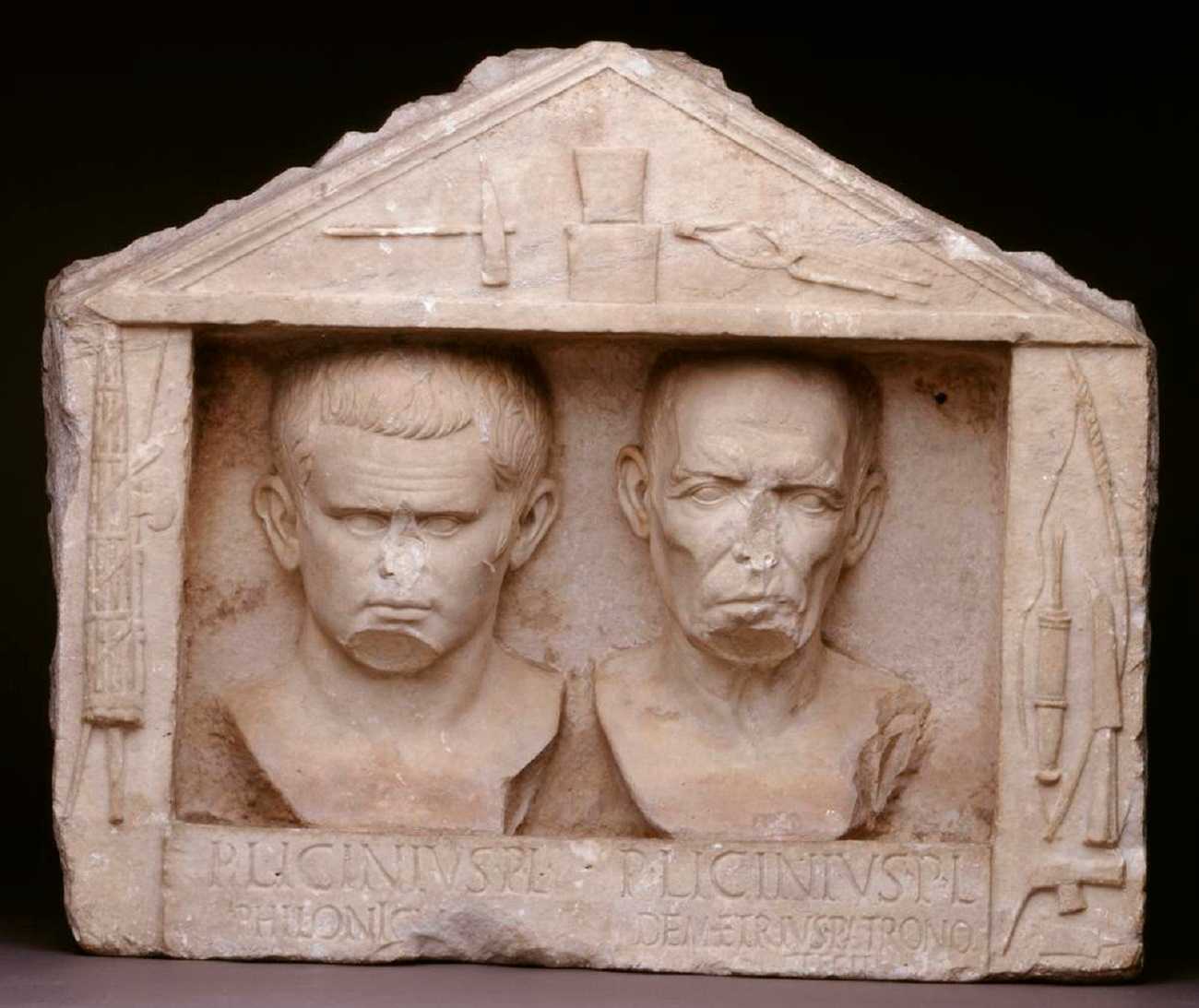

Julius Caesar’s secretary, Publius Licinius Apollonius (also known as Apollonios), served as a secretary to Caesar and Crassus and participated in Caesar’s invasion of Gaul. He wrote a biography of Caesar and Crassus after receiving his freedom, which Cicero (b. 106 BC), the preeminent thinker of the day, praised. Many people believed it to be the best primary source on the two titans of the Roman Republic; however, this work has since vanished.

One was not fully “free” in the daily life of Rome, even after being granted freedom. This was due to the fact that they were unable to break out of the aforementioned patronage structure. The recipients of “freedom” were expected to feel a deep sense of gratitude to their former masters to continue living as free citizens. But they were still entitled to a wage and civic rights.

When a Roman slave achieved freedom, he or she was expected to adopt the surname of his or her former owner. It is believed that Publius Licinius Apollonius was granted his freedom by Publius Licinius Crassus (he was one of the sons of Marcus Licinius Crassus).

The Daily Life of Ancient Roman People

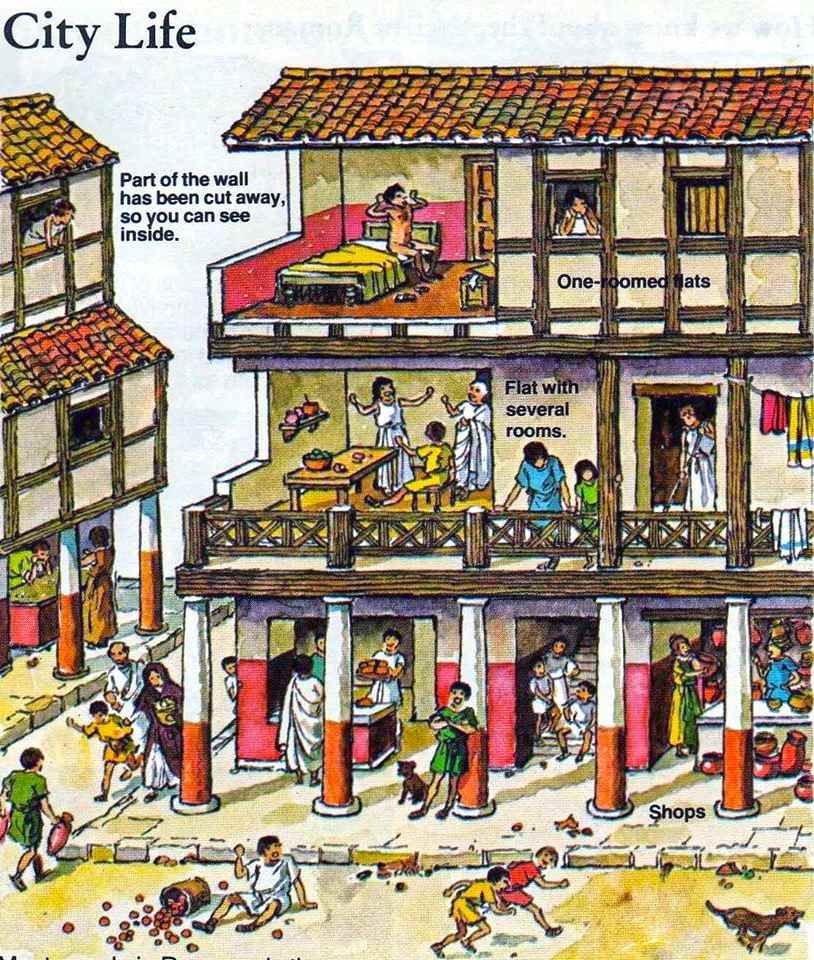

Houses

The typical Roman citizen did not live in one of Rome’s many marble or elegant timber homes located in the city’s historic center, as did the city’s richest families.

The typical Roman residence was an insula, a low-ceilinged, three- or four-story house constructed of brick or wood. Multiple households or people shared a single level with little separation between rooms.

Typically, a family or landlord would pay a year’s worth of rent in advance to live on the insula’s first level since it was the costliest. The lower floors had an advantage in terms of heating. It was easier to keep them slightly cooler in the summer but also warmer in the winter. In addition, the ground floors of many insulas housed a variety of shops.

In contrast, upper floors often offered lower rentals, paid either daily or weekly. People slept on the floor, couches, and even on each other’s laps, while many shuffled between temporary homes.

Extreme summer heat and bitter winter chills characterized the daily lives of the ancient Romans. The upper floors of many structures lacked even basic amenities like windows. Therefore, the lack of privacy was to be expected.

Making a Living

The vast majority of Romans originated in rural areas. Around the 1st century BC, the Italian provinces underwent a period of profound transformation. Slaves increased in quantity, allowing prosperous big farmers access to cheap or free labor, allowing them to prosper even more. It was becoming more difficult for small farmers to survive without the aid of slaves, and many of them were migrating to the cities.

Nevertheless, even in the city, it was difficult to find a job. As previously stated, a significant portion of slaves were allocated not only to miners and farmers but also to craftsmen, educators, and various professions.

This arrangement proved beneficial for those fortunate enough to possess slaves, but conversely, it resulted in a surplus of individuals struggling to secure stable employment. Consequently, the cities became crowded with individuals unable to find regular jobs.

During times of famine or temporary scarcity, the Roman government maintained a policy of distributing cheap bread and wheat to the needy. For many Romans, this was an absolute requirement in their daily lives, especially given the reliable supply throughout the Late Republic.

By today’s standards, many Romans subsisted on a diet of nothing more than bread, olive oil, a little cheese, and wine. Fruits and vegetables were sometimes offered in baked or boiled forms. It seems that wheat soup, similar to porridge, was the only fare of the lower classes of ancient Rome.

The meat was often reserved for the gods and only made accessible to the common populace during important festivals.

These vast supplies of wheat were imported from Sicily, a southern Italian island, as well as present-day Tunisia, known as the “African Province,” and Egypt, the world’s greatest wheat producer at the time.

The Ancient Roman citizens who were able to find employment often worked full-time, and the majority of them performed physical labor such as constructing and operating businesses, sailing ships, and transporting commodities.

The lowest class of people did not only consist of physical laborers but also included performers in the theater, prostitutes, and musicians.

Stores were owned and run by more prosperous middle-class households. Thermopolium, a public fast-food restaurant with a fixed menu, was one of several businesses in ancient Roman cities, as were wholesalers of spices and retailers of tools and timber.

Roman families with the highest riches were often families who had large farms or other sources of passive income, allowing them to devote their time and energy to politics and the arts rather than manual labor. Those seeking political office similarly prioritized their clients’ needs and aspirations while working to expand their own support base.

Working in the Army

Joining the Roman army was one option for the destitute to improve their social standing in the daily life of ancient Rome. Many young Roman men living in poverty actively sought out military duty because of the prestige that came with it.

For the most part, soldiers in the Roman army throughout the Early and Middle Republics were well-to-do free citizens since they had to pay for their own armor and weapons.

However, the number of free people able to purchase “middle-class aristocratic” armor and other things was steadily declining as a result of recurrent conflicts and the fast spreading of inequality, and the ancient Roman population was becoming permanently split between the extremely affluent and wealthy, on the one hand, and the impoverished, on the other.

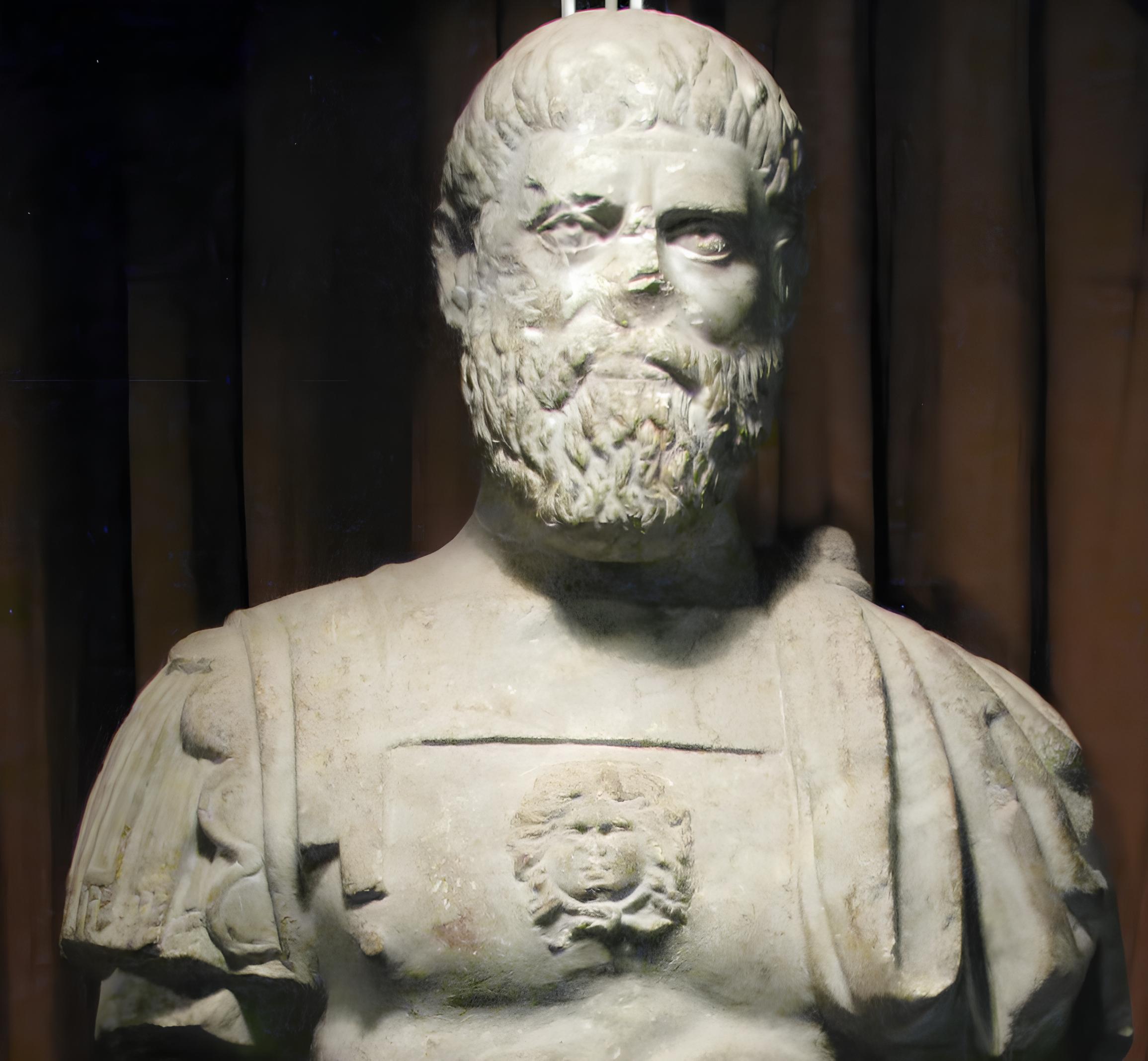

Therefore, a significant reform was instituted by the Roman general and statesman Gaius Marius (157–86 BC), who enlisted the help of impoverished Roman people as volunteer warriors and had the Roman government equip them with weapons and armor.

The system Marius created allowed for progression in the Roman army based on merit rather than social status. A common soldier from a poor family could rise to the rank of centurion, and all Roman soldiers, regardless of rank, received a retirement pension and land after serving for 20 years. Even a regular soldier was given some land.

In order to ensure that their troops were able to retire with the promised pensions, the great Roman generals carved up new regions and distributed the property of enemy rulers among the Roman troops.

Both Caesar and Augustus played significant roles in shaping the transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire by winning over the royalty of their troops and thus earning the devotion of the Roman people over the government.

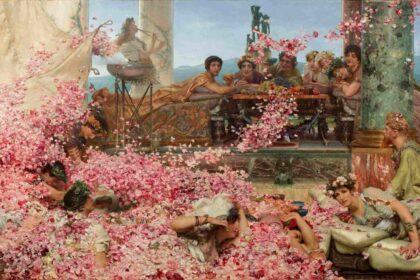

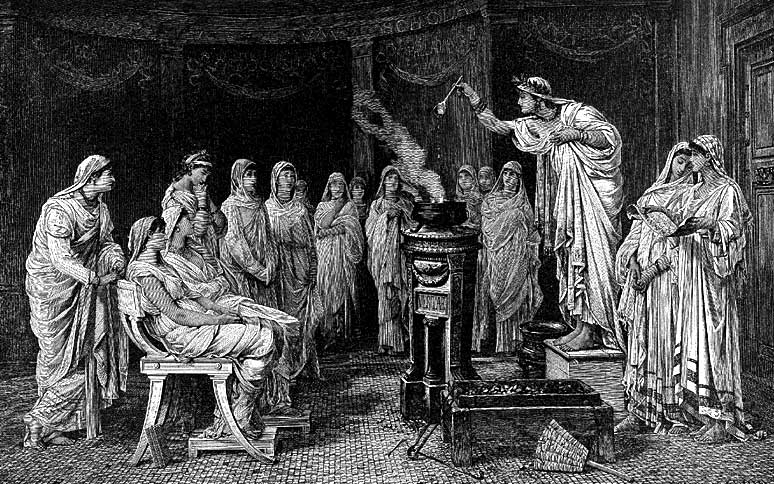

Festivities and Worshipping in Ancient Rome

The Romans had a polytheistic religion in which the Greek gods played an important role, although with Latinized names such as Jupiter for Zeus or Mars for Ares.

However, the Romans had a somewhat different understanding of religion than we do now. While today’s people still pray for success and believe in religions defining the concept of “right and wrong” or bringing “spiritual enrichment,” the Romans, with the exception of the Jews and the early Christians, did not practice any organized religion.

They still believed in deities whose power and influence were beyond human comprehension, but their gods were neither good nor wicked; they just existed.

Therefore, the Romans saw religion as a “covenant” rather than a “necessity”. In hopes that the gods would stop disasters from befalling Rome and safeguard its citizens, the ancient Romans wished to pay tribute to their deities by burning animal artifacts and performing sacrifices.

When the ancient Romans felt a god had violated their covenant, they often moved on to another god who was believed to be more “helpful.”

Considering there was no such thing as a “weekend” in Ancient Rome, the actual number of Roman holidays was not that different, considering people now get 104 days off in a year, including Saturdays, Sundays, and around two weekends for Christmas. There were numerous holidays in ancient Rome, and the total number of off days was more than a hundred.

Leisure Activities in Ancient Rome

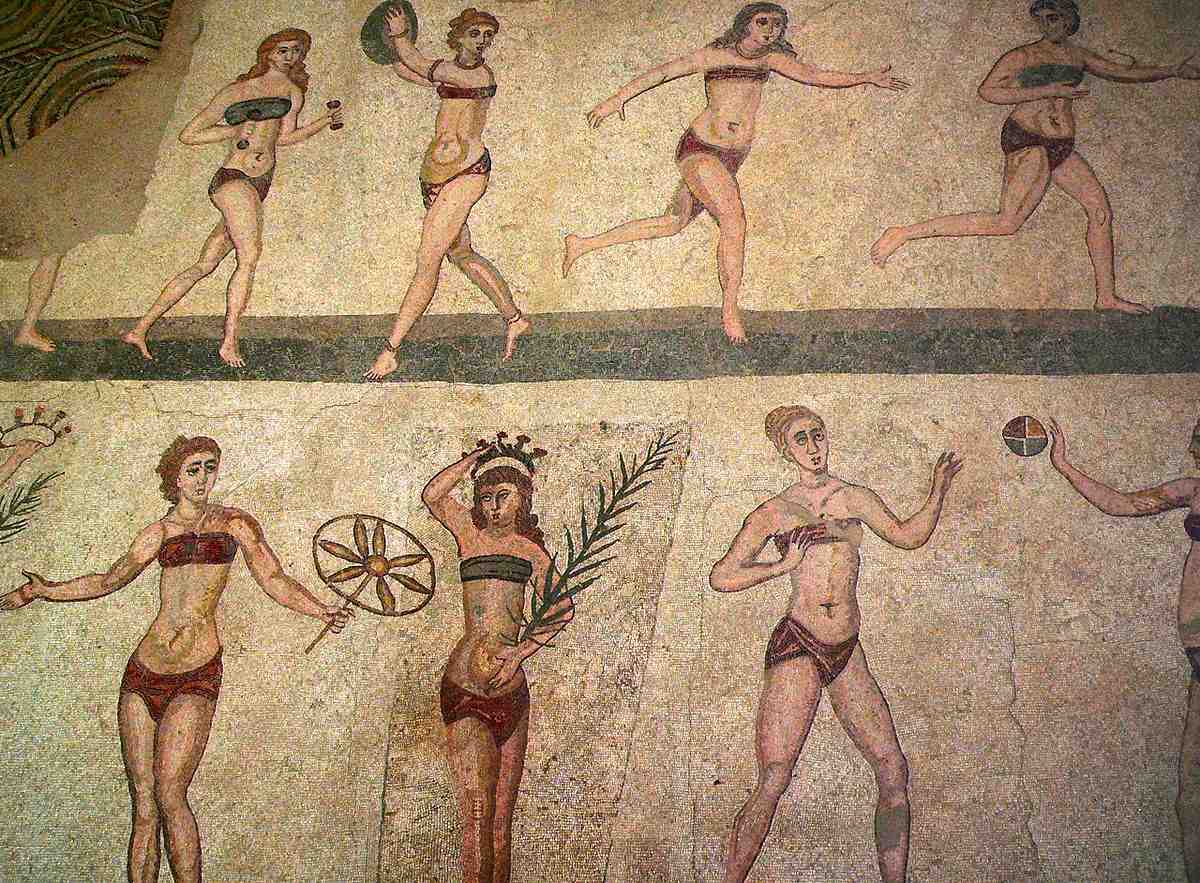

In the countryside, ancient Roman people worked in agriculture and mining all day long, whereas in the city of Rome, people worked from daybreak until noon, and then they slept in the afternoons. Afternoons were reserved for leisure activities like baths, swimming, playing sports, and going to the theater. During that time, most stores and businesses remained closed, with the exception of a few pubs and restaurants.

Sports enjoyed great popularity among men in ancient Rome. The city boasted impressive outdoor arenas where a wide range of athletic events took place, including wrestling, sprinting, long-distance running, javelin throwing, shot put, and many other traditional European sports that continue to be featured in the modern Olympic Games.

It was customary for participants to compete in the nude, emphasizing the raw physical prowess on display. However, it’s important to note that during this era, women were not permitted to enter the stadium and partake in these sporting spectacles.

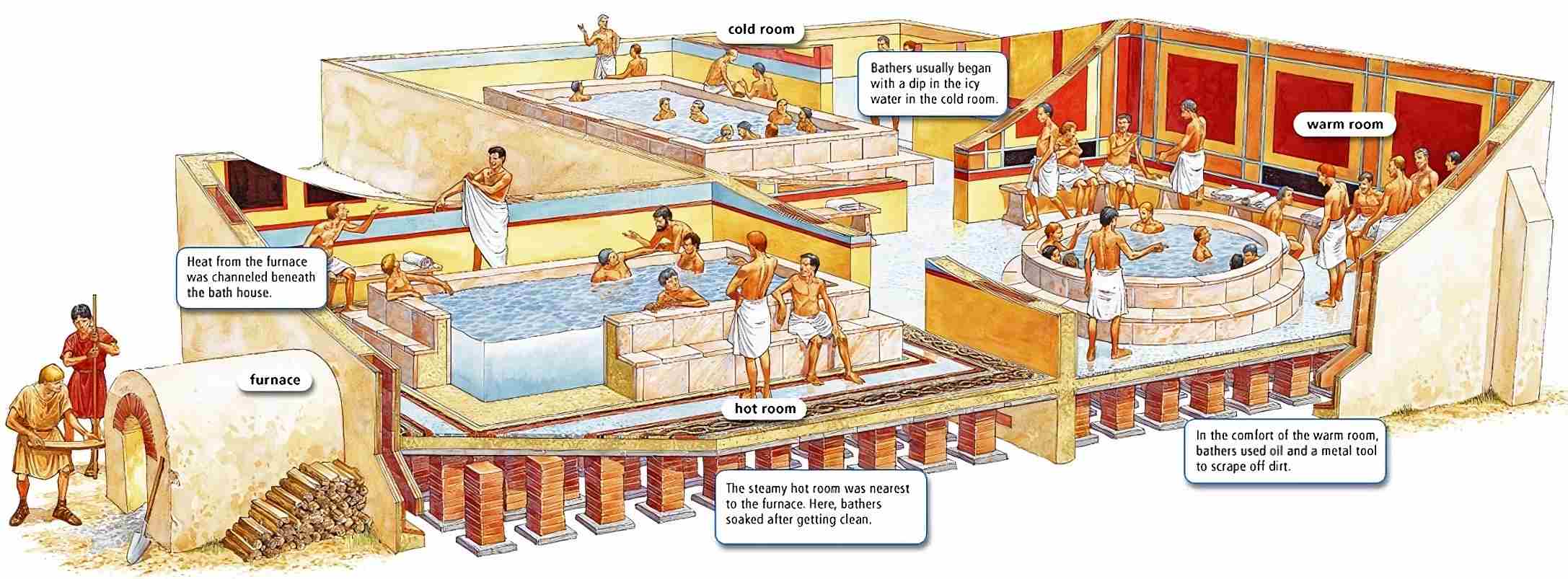

After a demanding day of games, the Romans would often unwind by indulging in the baths. However, it is presumed that those who didn’t appreciate athletics might have been deterred by the obligatory bathing that followed each session.

Public Baths

Public Roman baths were accessible to almost every free citizen for the minimal payment of a single copper coin. The wealthy had their own private baths. Almost everyone in the country could afford the price of a bath on a regular basis. The baths’ operating costs were modest, and wealthy donors and tax revenue filled the gap.

The culture of “bathing” was so integral to Roman identity that anyone who did not participate was called a “barbarian.”

There were not any shared showers or tubs, but rather individual ones for men and women.

In Rome, the public baths offered a range of amenities beyond just hot bathtubs. These bathing complexes featured cold baths, saunas, dedicated spaces for massages, rooms for applying soothing olive oil to the body, and an array of other facilities for a comprehensive bathing experience.

Ancient Roman people often took long, relaxing showers, sometimes lasting several hours, since doing so was considered culturally appropriate.

There were chairs and other seating options available in the open area next to the bathhouse. Having a public gathering spot where people from all walks of life could mix without regard to their social standing must have been a social boon.

Moreover, the baths served as a bustling hub where individuals could purchase food, witness captivating theatrical performances, listen to passionate poets recite their verses, witness politicians endeavoring to elucidate their policies and garner support, access libraries, utilize diverse amenities, and witness the congregation of people from many classes.

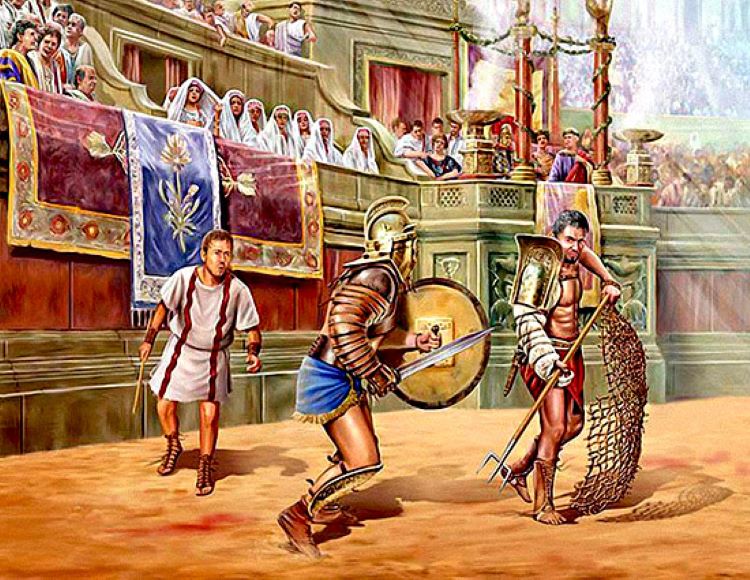

Sports and Gladiators

Last but not least, the Romans loved lavish spectacles on their most important festivals.

The quickest charioteers, like today’s sports stars, attracted a large following of devoted supporters and were divided into teams of red, blue, green, and yellow.

The arena also hosted large-scale gladiatorial contests, savage animal hunts, and simulated battles. Thousands of onlookers watched as rigorously trained slaves fought and killed each other.

Hollywood is responsible for popularizing the misconception that all vanquished gladiators were summarily executed. In reality, gladiators were not always murdered after a fight. In movies, a down thumb implies “kill,” but in reality, it meant the opposite.

A thumbs-up pointing to the chest signified the action of stabbing the sword into the chest of the defeated gladiator. Similarly, a thumbs-down represented the act of placing the sword on the ground or lowering it, sparing the gladiator’s life.

Gladiators were subjected to both one-on-one duels and mass spectacles of simulated battle. Julius Caesar once staged a simulated naval battle by floating vessels in the arena (which was filled with water) and having hundreds of gladiators fight to the death.

The prospect of stardom appealed to some gladiators, but many slave gladiators reportedly resented their circumstances, which is quite understandable.

For example, in the Third Servile War (73–71 BC) instigated by Spartacus, as many as 120,000 slaves joined the uprising, including numerous gladiators, causing significant trouble for the Roman army, as is well known.

Despite the harsh living conditions, it appears that this kind of “exciting” entertainment was one of the reasons why people continued to gather in the city of Rome. Because such large-scale entertainment was not available in the rural provinces. There were still some small-scale arenas in provincial ancient Roman cities.

This is what daily life was like for the average Roman citizen.

References

- Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome – Donald G. Kyle – Google Books

- Historia Augusta, The Lives of the Thirty Pretenders, III et XXX.

- A History of the Later Roman Empire by J. B. Bury – Cambridge.org