Let’s have a look at who Dr. David Livingstone was, his early life, and his death on the African continent. This famous explorer spent 30 years of his life living in Africa and exploring every point of this “dark continent.” He is perhaps the person who caused today’s Africa to be so doomed by the colonial empires.

Dr. David Livingstone and the exploration of Africa

The Scottish missionary and explorer David Livingstone had been fighting for his life for two weeks in an African village at the tip of Lake Tanganyika. Just when he was about to die of illness, hunger, and thirst, he stumbled upon a village in Ujiji after tramping for 350 miles (563 km). However, the stocks of food, medicine, and a small group of servants that had to be there waiting for him were sold by unscrupulous porters. Livingstone was too sick to walk the 780-mile (1255 km) road to the east coast, and since he had nothing to trade with anyone like a cloth or a bracelet, he fell into a pitiful situation and had to beg from Arab natives for food and clothing.

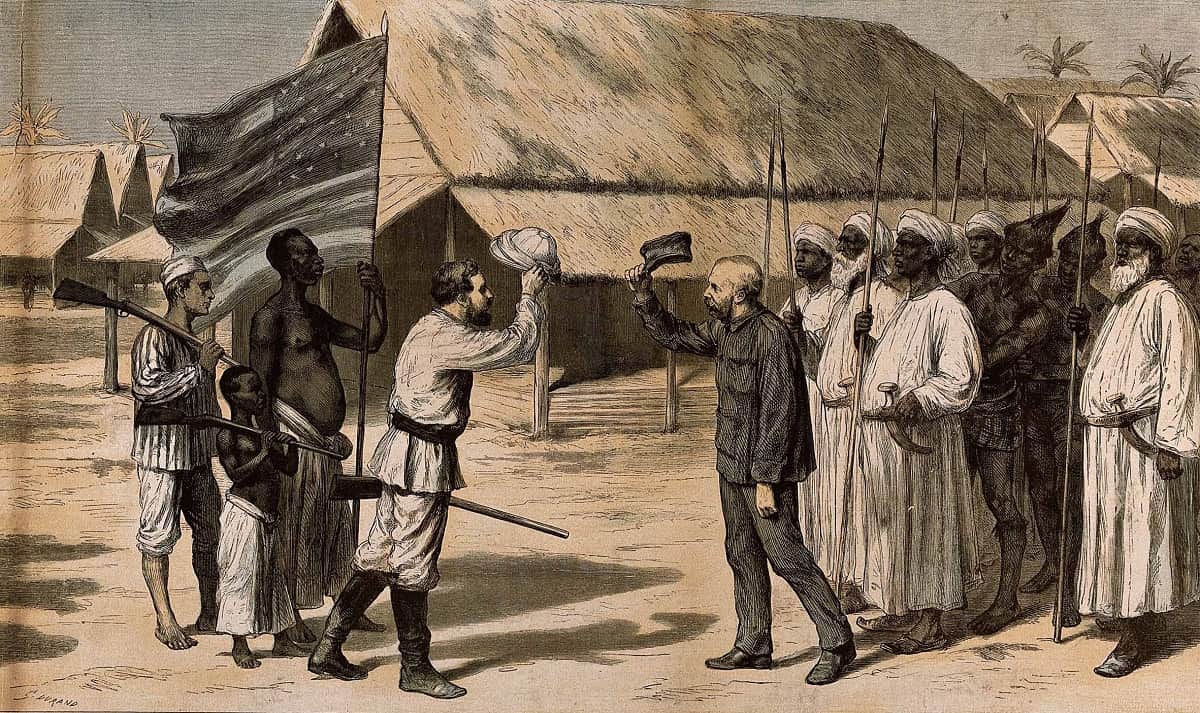

“Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

In his diary, he described himself as a “beanpole” and admitted that his mood was incredibly bad. Then, suddenly, at noon on November 10, 1871, Livingstone’s English-speaking servant Susi rushed to him and shouted excitedly, “An Englishman,” “I see him!” When Livingstone limped off to the village square, he saw the American flag waving in front of a large, rich caravan. Then a stocky, bearded man with a long leather boot, the head of the caravan, came forward solemnly, lifted his hat, and said, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” The New York Herald newspaper asked the English-American journalist Henry Morton Stanley to find Livingstone.

A few minutes later, Stanley was sitting with Livingstone on the tembe, the veranda of his house, whose walls were made of clay. On Livingstone’s insistence, Stanley quickly listed the news from the outside world, including a description of the Suez Canal, which had recently opened and about which Stanley had written an article.

The 58-year-old Scot was all ears with his faded red vest and a worn blue cap on his head. Since it had been more than five years since his departure from London, a bag of letters from his family and friends was now standing on his knees, waiting to be read. Stanley opened a bottle of champagne and took out two silver cups. He handed the goblet, having filled it to the brim, to Livingstone. “To your health, sir,” he said, raising his goblet. “And to yours too,” Livingstone responded softly.

Finding the source of the Nile River

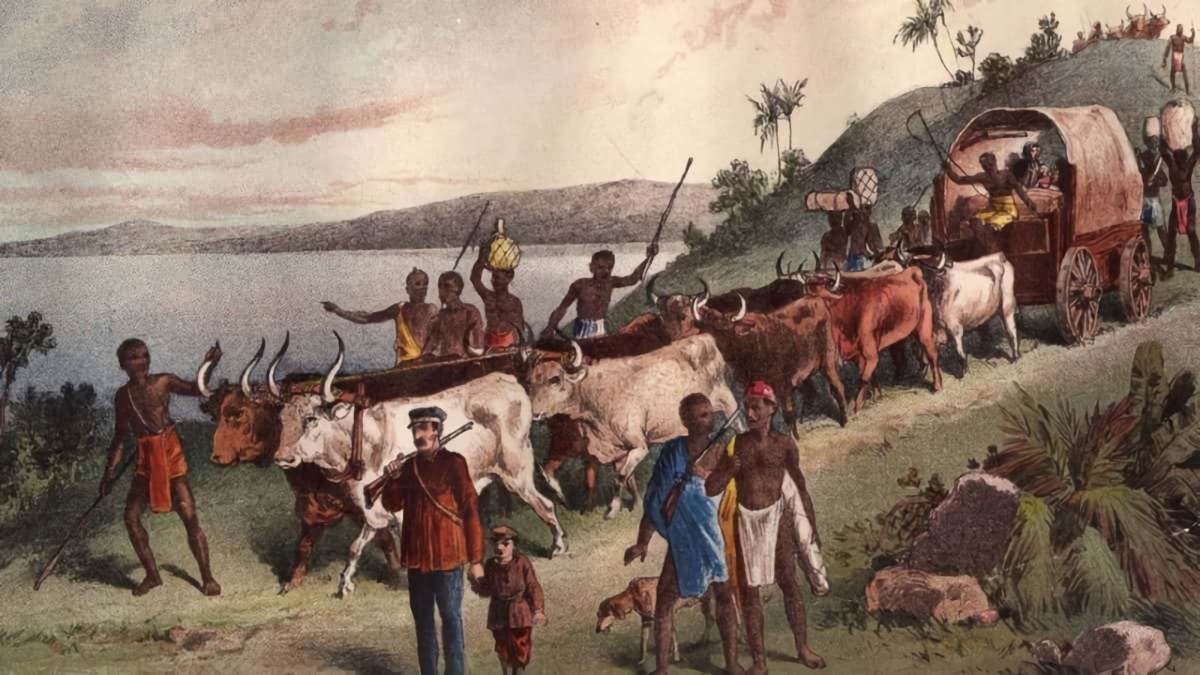

David Livingstone was one of the most admired people in the Western world at the time. For 30 years, he spent his energy and talents trying to bring Christianity to Central and East Africa and also end the slave trade that continued in those areas. He had traveled on the back of a pedestrian, a mule, or an ox for a million miles (1.6 million km) in Africa without minding the desert, forest, or marshland. He created the maps of the lands and continued his mission by saying he would either find a way inside or he would disappear.

During his travels, he mapped the Central African river system and traced the Zambezi River to its source. His experience as an explorer led him to an inevitable goal: he had to find the source of the Nile River. He started his research in 1866, but no news was heard from him for a long time. Then, there started an intense public opinion in order for him to be found.

There had been unfounded reports before that he was killed by African Zulu people, but this time he could have indeed died. Research delegations were sent to locate Dr. David Livingstone, and the delegation led by 30-year-old Stanley was one of them. Although Stanley was venturous and assertive and Livingstone was sullen and thoughtful, these two people, who are very different from each other in terms of age and creation, soon became the closest friends. “You gave me a new life,” said Livingstone, who wanted to express his heartfelt debt while his friend was making him eat nutritious soups and meat dishes. But most of his teeth were rotten and shed, so he had difficulty eating.

Thanks to the food and the medicines Stanley brought, David Livingstone soon regained his former health and strength. The two then took with them as many as twenty locals and went out to explore the northern stretches of Africa’s Tanganyika Lake. But when they realized that the water did not flow out of the lake, it was fairly disappointing. On the way back, Stanley got a fever and dysentery. This time, it was Livingstone who played the doctor and nurse. When they returned to Ujiji, the fully recovered Stanley begged Livingstone to give up the Nile obsession and return. But Livingstone refused the proposal.

David Livingstone is dying

After spending an unforgettable four months together, the two companions said goodbye to each other in tears on March 14, 1872, near Tabora, the largest city in Central Africa. Stanley pledged to send supplies to Livingstone, such as carriers, food, and medicine, to help him continue his research. Livingstone stubbornly hit the road again that August and searched for lakes and mountains to the south of Lake Tanganyika for eighteen months. He became increasingly weak, sick, and sluggish from dysentery and loss of blood due to hemorrhoids. Since he was too sick to get on the mule, he had to walk in swamps while the rain bucketed down.

Sometimes he found himself in black mud to his knees; ants, mosquitoes, and venomous spiders never left him alone. When he could no longer eat or walk, his men carried him on logs. “Knocked up quite and remained—recovered—sent to buy milch goats,” Livingstone wrote in his diary on April 27, 1873. “We are on the banks of the Molilamo.” The next day, they moved Livingstone to Chitambo, in the southeast part of Lake Bangweulu.

In a hut made of mud, he was laid on a bed of grass and wands. He drank some chamomile tea and told his servant, Susi, to leave him alone. Just before dawn on May 1, David Livingstone’s death was noticed by an African boy sleeping at the door of the lodge. Kneeling next to the bed, Livingstone’s gray-haired head had fallen into his hands as if he were praying.

Who was Dr. Livingstone?

David Livingstone, the son of a poor Scottish family, was born on March 19, 1813, in the industrial town of Blantyre in the Lanarkshire region. When he was ten years old, he started working in a cricket workshop and spent 14 years there. At the same time, he went to evening school, learned Latin and Greek, and decided to become a missionary physician in China.

Livingstone became a doctor after studying medicine in Glasgow in 1840, and he was accepted into the priesthood by the London Missionary Association. When the Opium War prevented him from going to China, he set out for South Africa and arrived in Cape Town in March 1841. The search for people to adopt Christianity led him to the dangerous Kalahari region, and by the summer of 1842, he had gone further north than any white person before him.

Two years later, Livingstone was attacked by a lion when he was about to set up a mission center on the border of the Kalahari Desert; he would never be able to lift his left arm higher than the shoulder. In 1845, he married Mary Moffat, the daughter of a missionary, who participated in many research trips with him. Livingstone also launched a campaign against the slave trade, which was mostly directed by the Arabs on the east coast.

In 1852, he went on a four-year expedition. During this trip, he tried to determine the trade routes and to place indigenous missionaries in the Transvaal region. He acquired a wealth of information on Central Africa and was welcomed as a hero when he returned to England in 1856. The British government made a monetary contribution to his next research trip; thus, from 1858 to 1864, he would continue exploring the Zambezi River. During this time, his wife died and was buried in Africa. Livingstone’s last expedition to search for the source of the Nile River began in January 1866.

How did Stanley become an explorer?

Born on January 29, 1841, in the town of Denbigh in the Wales Region, Stanley fled to Liverpool in his youth, boarded a ship as a crew, and went to New Orleans. There he became friends with a cotton broker named Henry Stanley, who gave him his name. After serving as a Confederate soldier in the American Civil War, Stanley turned to journalism. In 1868, he joined a British force sent to save British diplomats and their families imprisoned in the capital city of Magdala, in Abyssinia.

It was Stanley who first wrote in the New York Herald newspaper how the sent force captured Magdala, freed the British, and then looted the city. This scoop made the 27-year-old reporter, who later used the name “Morton” to be more effective, one of the leading journalists in the world. In 1869, the owner of The Herald, James Gordon Bennett’s son, called Stanley to Paris and told him to “find Livingstone.”

After Livingstone died in 1873, Stanley took over the African expeditions from where the Scottish left off. He traveled all around Victoria and Tanganyika lakes. He went down from the Congo to the lake he called Stanley Lake, and from there to the waterfalls he called Livingstone Falls. In 1879, he helped establish the Congo Free State with the support of Belgian King Leopold II. When he returned to London in the 1890s, he was elected deputy for the North Lambeth area and was given the title “Sir.” He died in May 1904 and was buried near his home in Pirbright, Surrey, England, his hometown.

Why were Livingstone and Stanley criticized?

Despite all the praise and reward for Livingstone and Stanley, some people did not find these two researchers admirable. The Royal Geographical Society did not see Livingstone being discovered in the middle of the African forest as an exciting newspaper article. Sir Henry Rawlinson, the president of the association, said that “it was not Stanley who had discovered Livingstone, but Livingstone who had discovered Stanley.”

Stanley was accused of treating African workers as “savages” and using unnecessary violence against the indigenous people who came his way. Although Livingstone generally got along well with the carriers, he had a fight with them on his last trip, causing several of them to escape. Scot was also chastised for failing to complete many of the tasks he set out to do.

For example, he was not able to establish a single mission center in all his time as a missionary. He had also lost his way in researching the source of the Nile River. More specifically, he had not done anything for the illness that resulted in his wife’s death, and he had also left his children alone at home for years.

More importantly, Livingstone and Stanley whipped up the enthusiasm of people and states for the discovery of Africa. Because this effort implied a desire to acquire new lands. At the beginning of the 20th century, the five countries participating in this race—England, Belgium, France, Germany, and Portugal—shared most of the African continent among themselves.

Bibliography:

- “David Livingstone (1813–1873)”. BBC – History – Historic Figures. 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Easton, Mark (3 September 2017). “Why don’t many British tourists visit Victoria Falls?”. BBC News. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Bayly, Paul (2013). David Livingstone, Africa’s greatest explorer : the man, the missionary and the myth. Stroud. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-78155-333-6. OCLC 853507173.

- Jeal 2013, p. 289.

- Mackenzie, John M. (1990). “David Livingstone: The Construction of the Myth”. In Walker, Graham; Gallagher, Tom (eds.). Sermons and battle hymns: Protestant popular culture in modern Scotland. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0217-9.

- “David Livingstone Centre: Birthplace Of Famous Scot”. Archived from the original on 12 February 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Ross 2002, p. 6.

- Blaikie, William Garden (1880). The Personal Life of David Livingstone… Chiefly from His Unpublished Journals and Correspondence in the Possession of His Family. London: John Murray – via Project Gutenberg.

- Jeal 2013, p. 13.

- Vetch, Robert Hamilton (1893). “Livingstone, David” . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 33. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 385.

- Ross 2002, pp. 9–12.

- Lawrence, Christopher (2015). Wisnicki, Adrian S.; Ward, Megan (eds.). “Livingstone’s Medical Education”. Livingstone Online. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- “The University of Glasgow Story : David Livingstone”. University of Glasgow. n.d. Retrieved 12 July 2018.