This Article at a Glance

What was the social status of American soldiers during the Whiskey Rebellion?

Most American soldiers during the Whiskey Rebellion came from ordinary or poor families and had low social status. The officers, on the other hand, were generally from upper-middle-class families, many of whom were plantation owners. More than one-third of the officers’ ancestors were officers in the Continental Army (1775) or militia during the Revolutionary War.

How did the officers treat the soldiers during the Whiskey Rebellion?

There was a clear class distinction within the US military during the Whiskey Rebellion, and officers treated soldiers with great disdain. The officers had many privileges that the soldiers did not, such as the ability to resign and leave the garrison at any time. They had no shortage of supplies and lived in warm and comfortable cabins, while the soldiers could only sleep in the wild or in tents. Similarly, if the American soldiers were caught drinking or gambling, they would be heavily punished, while the American officers were not held accountable.

What were the punishments for American soldiers during the Whiskey Rebellion?

Due to hunger and differential treatment, many soldiers had to resort to looting civilian homes to obtain food. However, if caught, they would be heavily punished by the officers. For example, a Virginia volunteer was whipped 100 times for stealing a beehive, and narrowly escaped death. The officers implemented strict punishment standards, such as whipping a soldier 50 times for stealing a blanket or using branding punishment.

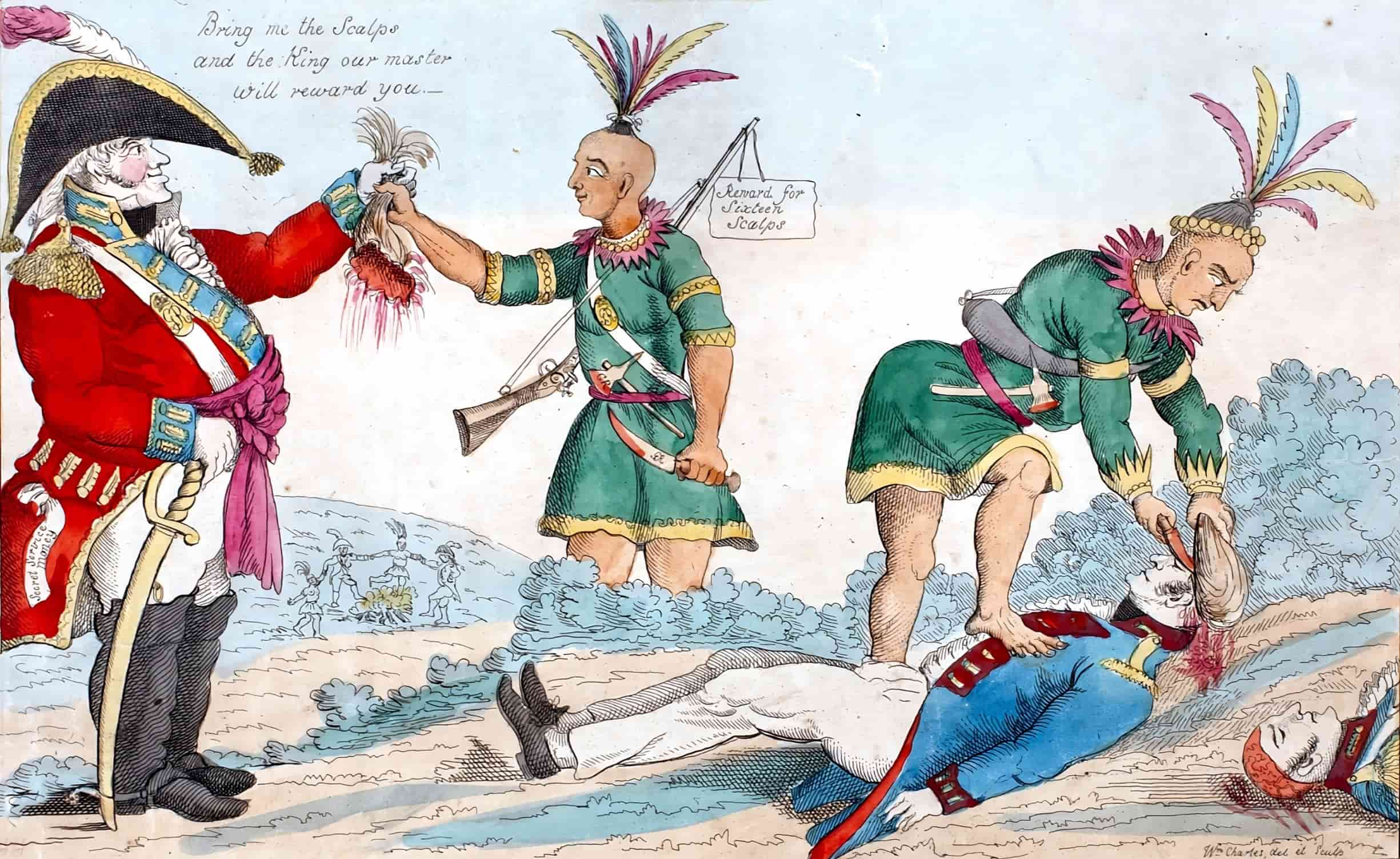

American soldiers had a tough time back then: They received poor treatment and faced strict military law, and officers even offered bounties on the scalps of deserters to Native Americans. Shortly after the United States was founded, it faced a major problem: the Whiskey Rebellion (1794). Although not well-known today, this rebellion had the potential to divide the newly established country. To quell the uprising of western citizens, the first US president, George Washington, had to organize over 13,000 soldiers, which was more than the number of troops used in several battles during the Revolutionary War, demonstrating the severity of the situation.

Poor Supplies and Discipline

Because quelling the rebellion was such an important event for the newly established United States, many people wrote memoirs of the entire process, recording various details. Interestingly, after reading these memoirs and letters, it becomes clear that the lives of American soldiers at that time were not very good.

Many of the 13,000 soldiers summoned by Washington were volunteers, mostly young people. Their parents had mostly participated in the Revolutionary War and fought against the British. These soldiers grew up listening to their parents’ stories and knew that the government had given many rewards, such as land permits (mostly in the western region), to show its appreciation for the help of the veterans.

When Washington began to call for volunteers, those adventurous American boys flocked to join, quickly filling Washington’s camp to be at his disposal.

Soon, the vast majority of the volunteer soldiers would be greatly disappointed with their military careers because they received orders to go to the west shortly after joining the military and before undergoing much military training. They had to endure rain, and mud, and cross the Appalachian Mountains with limited supplies while diseases ravaged their ranks, and their discipline was very poor.

The officers who were supposed to maintain discipline and lead the soldiers didn’t care about the lives of the common soldiers. As a result, the US Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton, was worried:

“Every unit lacks supplies, not a single shoe, blanket, or ounce of ammunition has been delivered to the troops on the front lines.”

The officers from the gentleman or plantation owner class only cared about rank and command, and they constantly fought with each other. They also focused most of their energy on debating the color, design, and accessories of their military uniforms.

As for the morale of the army and the issue of rations for ordinary soldiers, they showed little interest, and there was a huge gap between them and the soldiers. In any case, the officer class never went hungry.

The Gap Between the Officers and Soldiers

At that time, there was a clear class distinction within the US military. Officers generally came from upper-middle-class families, many of whom were plantation owners, and there were blood and family relationships among them, such as intermarriage.

In addition, more than one-third of the officers’ ancestors were officers in the Continental Army (1775) or militia during the Revolutionary War, while the soldiers generally came from ordinary or poor families and had low social status.

When the officers’ arrogance, ambition, fashion taste, and honor were not satisfied, they became angry and vented their frustration on the soldiers.

In addition, the officers had many privileges that the soldiers did not, such as the ability to resign and leave the garrison at any time, while the soldiers did not have this right. At the same time, the soldiers suffered from a lack of clothing and food, with many still barefoot even after a month of fighting.

The officers had no shortage of supplies and lived in warm and comfortable cabins, while the soldiers could only sleep in the wild or in tents. Similarly, if the American soldiers were caught drinking or gambling, they would be heavily punished, while the American officers were not held accountable.

In this situation, the officers’ journals read like tourist guides to the scenery and taverns along the way. Many officers described to their families the “mountains of beef and oceans of whiskey” they saw in the army. On the other hand, the soldiers’ journals were more like survival guides, describing weeks of hunger and cold in detail.

Severe Punishments for the American Soldiers

Due to hunger and differential treatment, many soldiers had to resort to looting civilian homes to obtain food. However, if caught, they would be heavily punished by the officers. For example, a Virginia volunteer was whipped 100 times for stealing a beehive, and narrowly escaped death.

Despite such severe punishment, soldiers in desperate hunger would still loot homes, tear down fences for firewood, and steal all the chickens, cows, and sheep they could find.

Even if the rebellion was successfully quelled and the rebellion leaders were caught, the soldiers who remained in the army did not have much of a better life. They were ordered to stay in the local area, still suffering from lack of clothing and food, and had to endure cold and torture. As one officer wrote in a letter to his family:

“The soldiers are in really bad shape, completely exposed to the bitter cold, with little good shelter, only small tents that can squeeze eight men, and many of them are sick. […] You should have received the recent regulations issued by our generous Congress for the distribution and dispensation of food and straw to the garrison. […] The allowances are really far below what they should be, and I am really confused about where to go next. Please do tell me the plan you will take; I’m pretty sure the soldiers can’t possibly sustain themselves on this food.”

To prevent this situation, officers implemented strict punishment standards (whipping was very common, while branding punishment was relatively rare but still existed), such as whipping a soldier 50 times for stealing a blanket, or 100 times for assaulting an officer.

The discipline requirements for soldiers were also extremely strict. Even if a soldier was resting instead of holding a gun properly while on guard duty, he would be sent to a military court.

Native Americans as the Bounty Hunters of Deserters

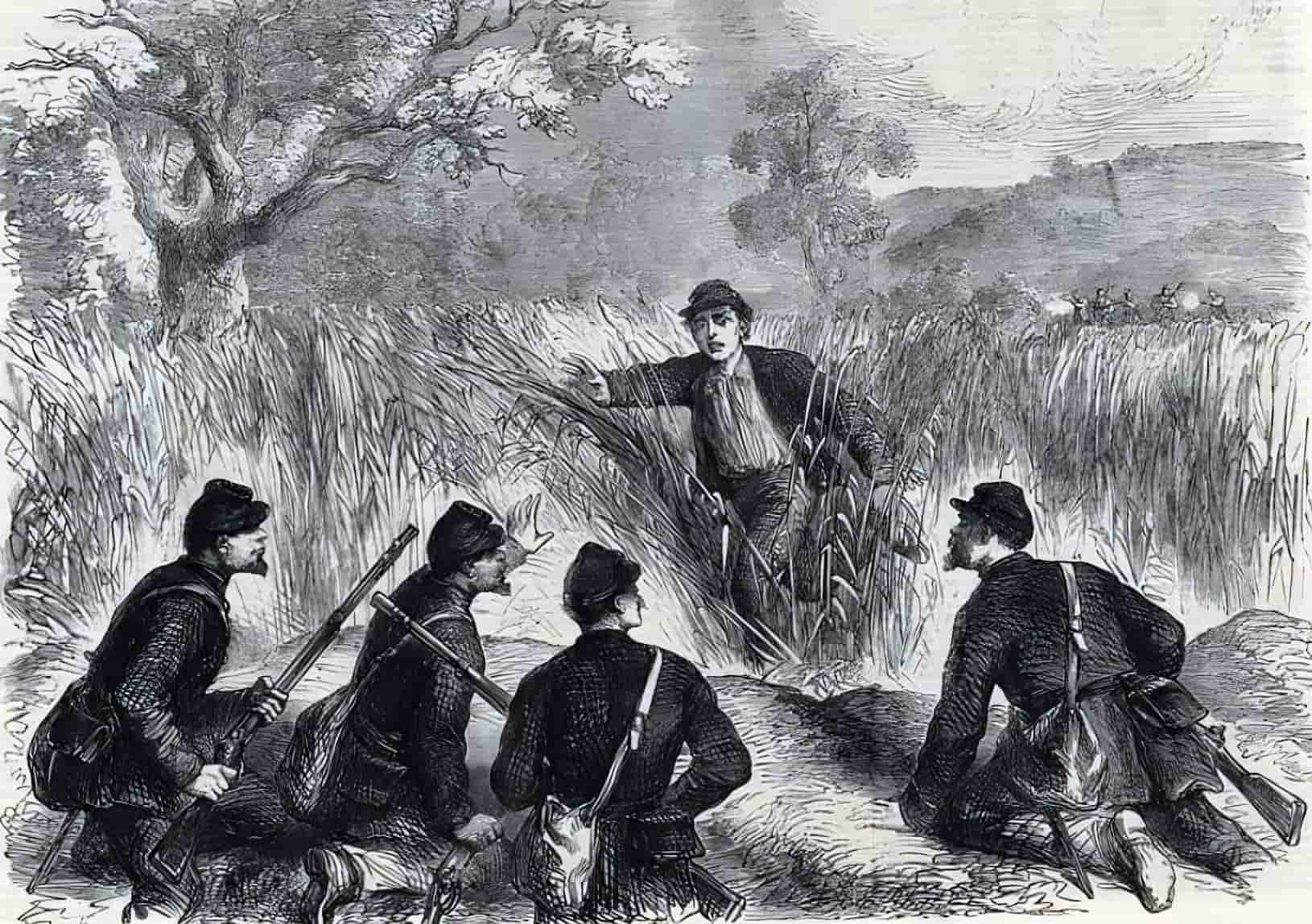

Under these circumstances, the soldiers were extremely dissatisfied, and desertion behavior frequently occurred. The officers had to send out patrols every morning to search for deserters, and then publicly punish the captured deserters with 100 lashes.

Many deserters were whipped to death, but it was still ineffective because it was difficult to catch all the deserters. At that time, the soldiers were stationed in sparsely populated fields, and the deserters could easily hide in the vast border areas.

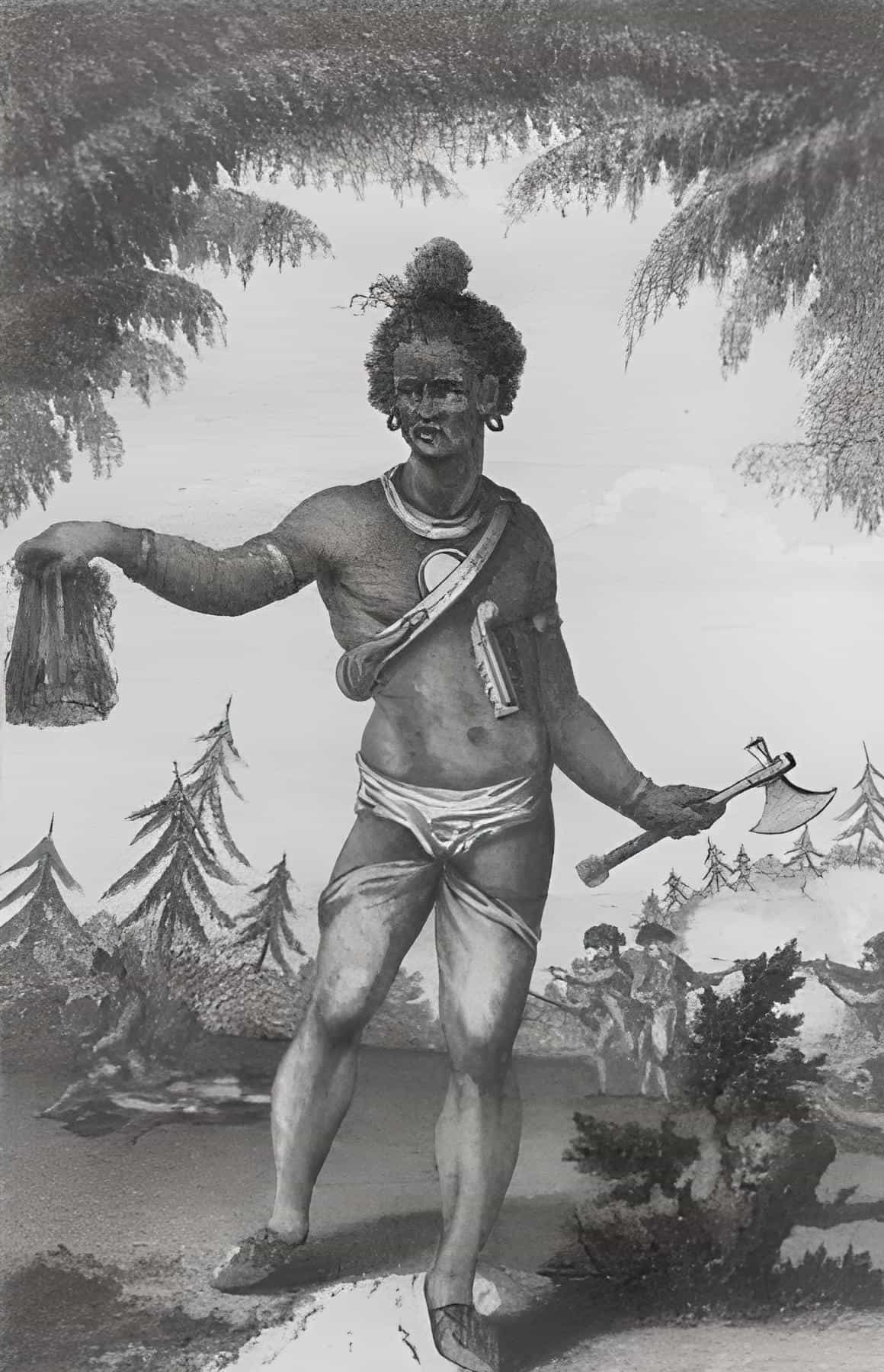

In order to punish deserters as much as possible, officers spared no effort in finding Native Americans who were good at wilderness tracking to act as bounty hunters. They used indigenous people to catch deserters. In the autumn of 1795, when officers learned that a deserter had run away, they immediately offered a bounty of $10 for the person alive and $20 for their scalp to two Shawnee Native Americans.

Yes, a deserter was more valuable to the army when he was dead. The Native American bounty hunters brought back the scalp of the deserter the next day and received the officers’ appreciation and a reward of $20.

It was white people offering a reward to Native Americans for the scalps of their fellow white men, which the Native Americans found quite amusing and absurd.

References

- [PDF] – A Cultural History of the Scalping Paradigm – Open.library.ubc.ca

- James Sharp – 1993. American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. ISBN 9780300065190.

- Russel Thornton – 1987. American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492. Russell Thornton – ISBN 978-0-8061-2074-4.