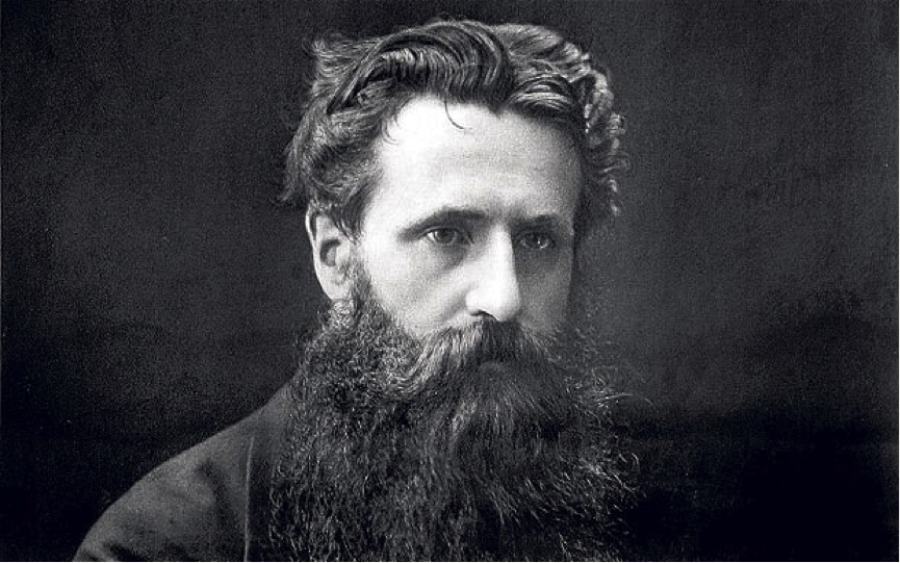

George Smith, a regular visitor to the British Museum in London, made a remarkable discovery in November 1872 while poring over a piece of a clay tablet inscribed in cuneiform. Smith allegedly leaped up in excitement and stripped down to his underwear. It’s debatable if this really occurred. Without a shadow of a doubt, the 32-year-old had just discovered the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the greatest literary masterpieces ever written and thought to have been lost for nearly 2,000 years.

Despite his lack of any scientific training, Smith had a lifelong fascination with the history of bygone civilizations. Smith, who was born in 1840 to a working-class family in London, trained himself to read cuneiform. After serving his apprenticeship as a printer, he decided to try his hand at banknote engraving, but the task did not satisfy him. He liked to spend as much time as possible perusing the British Museum’s treasures during his lunch break, so he commuted there daily.

Henry Rawlinson, a key figure in the decipherment of the cuneiform writing in the 1850s, noticed him there almost immediately. Rawlinson thought the young guy was promising and suggested that the museum hire him. The autodidact would now be responsible for reassembling the shattered clay tablets in the museum.

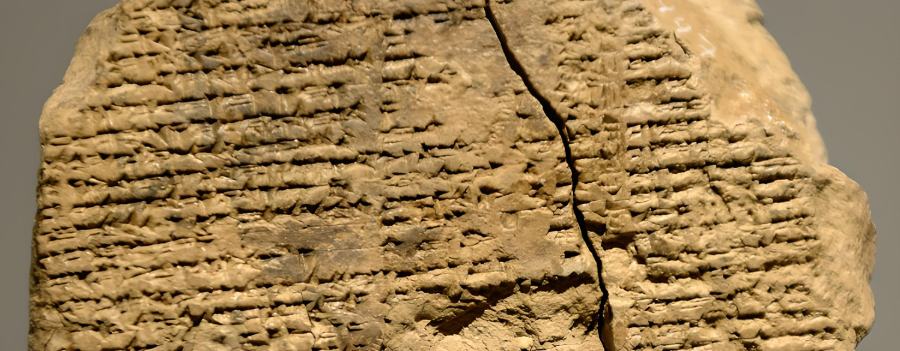

Throughout the 19th century, scholars gained a deeper familiarity with the cuneiform script. Smith uncovered what is perhaps the most crucial text in this cryptic writing.

A massive collection of cuneiform texts

These clay tablets were mostly sourced from modern-day Mosul in northern Iraq, on the site of the ancient city of Nineveh. Historically, it was the capital of the Assyrian Empire. Around 650 BC, King Ashurbanipal commissioned the construction of an exceptional library. The collection was based on copies or confiscations of as many texts as feasible. However, in 612 BC, the palace and its library were completely destroyed in a fire. Broken into several pieces, the clay tablets were eventually lost for generations.

Smith, more than two thousand years after the clay tablets were first created, had the monumental chore of going through them. A considerable portion of the texts in the biggest collection of cuneiform writings dealt with administrative topics, such as invoices and receipts. But Smith was looking for books in a methodical way.

That day in November 1872, he finally located his prize. The piece he was reading mentioned a powerful tide, a ship, and a lost bird on the lookout for land. Smith was instantly conscious of the feeling, and he realized that he was experiencing a reenactment of the Flood from the Old Testament. But the clay tablet was written so much earlier than the Bible.

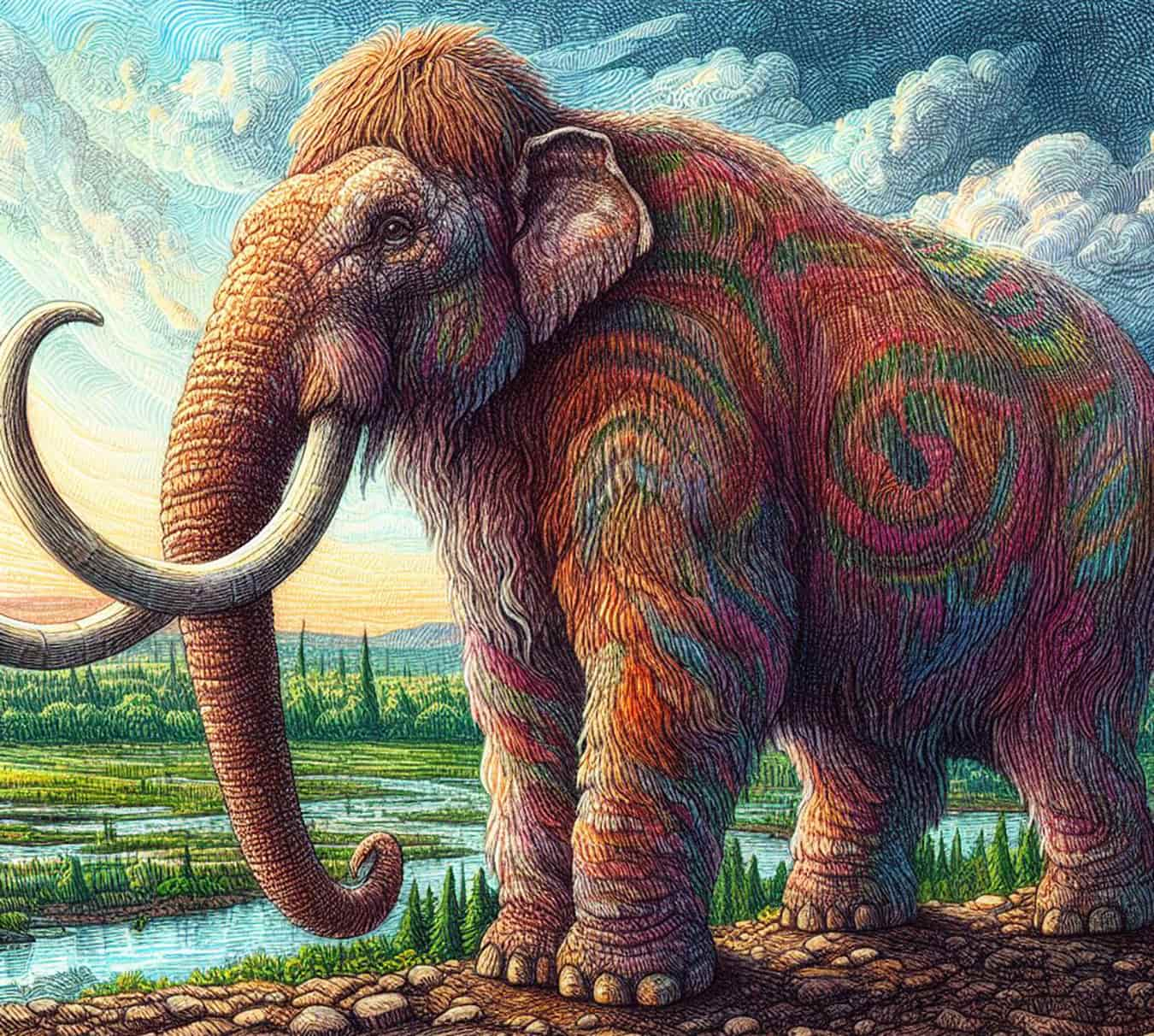

Smith unearthed a piece of a tablet containing the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the first works of literature ever written. Gilgamesh, ruler of Uruk (where cuneiform writing was developed in the 4th millennium BC), oppressed his people, so the gods created Enkidu to fight against him.

Enkidu and Gilgamesh became friends, and the two went on many adventures together until it was obvious that Enkidu must die. In a conference, the gods reached a conclusion, and Gilgamesh was now on a mission to live forever. Once he reached Utnapishtim at the edge of the world, he learned about the Flood from him. Gilgamesh finally went back to his home city of Uruk.

In all, there are 12 panels making up the Epic of Gilgamesh. Currently, just 38% of the original text’s 3033 lines have been preserved in their entirety. The Library of Ashurbanipal provided the majority of the textual remains.

Smith conducted excavations in Mesopotamia to locate the missing pieces

Due to his limited knowledge of the Mesopotamian Flood narrative, Smith in 1872 was unaware of this. So, he prepared for his own excavation at Nineveh. Except that the British Museum wasn’t prepared to foot the bill for an expedition, thus money was needed. The Daily Telegraph provided financial support, and in 1873 Smith traveled to the Ottoman Empire in search of further information on the Flood in the remains of Nineveh.

On May 7, 1873, excavations started, and one week later, the buzz was at its peak: Smith had found a real discovery. He sent a hasty telegram to London, which was a huge blunder. Because the Daily Telegraph immediately asked Smith to return to London. Smith went home in dismay and resolved to go back as quickly as he could. A lot happened very quickly; he began the second dig in 1873 and returned to London in the summer of 1874 with a lot more fragments.

Finally, he was able to piece together the details of the Flood and other tablets from the Epic of Gilgamesh. The pace he set was astounding. By the end of 1874, he had published translations of all the literary writings he had unearthed, and the following year, he penned no less than four volumes. He acted as though he knew his time was running out.

Finally, at the end of 1875, he set out for Mesopotamia once more with the backing of the British Museum, but this time it was a tragic expedition. After first being denied access to the dig site, his travel partner later succumbed to cholera while they were still close to Baghdad. Smith was granted permission to excavate in Nineveh, but the extreme summer heat made the task hard.

When Smith got dysentery in Syria, he realized he couldn’t just go back to London without having accomplished anything. George Smith, a career switcher and self-taught scientist who paved the way for contemporary Assyriology, passed away in Aleppo on August 19, 1876. He was 36 years old.