Djoser was the first ancient Egyptian king (Pharaoh) of the 3rd Dynasty (Old Kingdom). He reigned from around 2720 to 2700 BCE, according to some estimates a few decades later in the 27th century BCE. He can unequivocally be identified with the contemporaneously attested Horus name Netjeri-chet. As the first builder of a step pyramid, Djoser is one of the most famous kings of ancient Egypt.

Name and Identity

The name “Djoser” can unequivocally be equated with the archaeologically well-attested Horus name “Netjeri-chet”. A convincing piece of evidence is a seated statue of Pharaoh Senusret II (12th Dynasty), the base inscription of which contains the name “Hor-Netjeri-chet-djeser”. This provides the earliest use of the name “Djeser” under Senusret II.

The second youngest evidence for the use of the name is provided by the famous Westcar Papyrus (13th Dynasty), which also uses the cartouche name “Djeser” for Djoser.

However, the subject of current research is the question of the origin of the name “Djeser”. Fragments of polished sandstone stelae from the Djoser complex in Saqqara may provide a possible clue. Their inscriptions mostly mention the names of Djoser and his wives and daughters, but always begin with the words “Chenti-ta-djeser-nisut” (blessed be the land of the exalted king). The “djeser-nisut” was probably misinterpreted as Djoser’s birth name in later times and adopted as a cartouche name.

Special attention is also given to cartouche name No. 16 in the Abydos king list of Seti I. Upon closer examination, it becomes clear that the name version there was originally not introduced with “Djeser”, but with another word. However, this was later chiseled out again. It is uncertain what this word was, and there are numerous interpretations.

Origin and Family

Djoser’s mother was Queen Nimaathapi, the wife of Khasekhemui, the last ruler of the 2nd Dynasty. It can therefore be assumed with high probability that Khasekhemui was also Djoser’s father. The only known wife of Djoser was Hetephernebti. The only child of Djoser mentioned is a daughter named Inetkaes. Whether she was also the daughter of Hetephernebti or from another marriage cannot be determined with certainty from the existing source material.

Another possible family member of Djoser is depicted on a relief fragment from Heliopolis, now housed in the Museo Egizio in Turin (Inv. No. 2671/211). The fragment shows the seated king, and in front of him, depicted much smaller, are his daughter Inetkaes and his wife Hetephernebti. Another person from behind holds the foot of the king. It is uncertain who this person is, as the inscription is very poorly preserved. Ann Macy Roth reads the name Niankh-Hathor and considers the depicted person to be another daughter. However, this reading is highly uncertain and has not been accepted in Egyptological research so far.

Possibly the mortal remains of one of Djoser’s female relatives have also been preserved. James Edward Quibell found several bones of a young woman in the Djoser pyramid complex in the early 20th century, whom he believed to be a princess. In 1989, radiocarbon dating of the bones was carried out. The results were rather imprecise but did not rule out dating the woman, approximately 16 to 17 years old, to Djoser’s time.

Pharaoh Sekhemkhet is generally considered Djoser’s successor.

Reign

Length of Reign

There are no contemporary inscriptions available to determine the exact duration of Djoser’s reign, so only information from later king lists can be relied upon. The Turin King’s Papyrus, which originated in the New Kingdom, mentions 19 years and 1 month, while the Egyptian priest Manetho, living in the 3rd century BCE, mentions 29 years. In research today, the statement of the Turin Papyrus is generally accepted, and a reign of 19 to 20 years is assumed.

Events

An inscription records Djoser’s assumption of power on the 26th of Achet III in the Egyptian season “Inundation” of the Egyptian calendar. Little else is known about events during Djoser’s reign. The Palermo Stone describes the first five years as follows:

| Year | Happenings |

|---|---|

| 1st year | Appearance of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt; unification of the two countries; Circumnavigating the White Walls |

| 2nd year | Appearance of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt; Presentation of the Sentj Pillars to the King of Upper Egypt |

| 3rd year | Escort of Horus; Creation of a statue of Min |

| 4th year | Appearance of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt; Stretching the string for Qebeh-Netjeru (“Fountain of the Gods”) |

| 5th year | Escort of Horus, Feast of Djet…. |

The fracture line of the Palermo Stone runs diagonally through the fifth window, which is why the rest of the entry is missing, making it uncertain which festival was precisely described.

Administration

Probably shortly before or during Djoser’s reign, there were initial attempts at a fundamental administrative reorganization of Egypt. While administration originally relied only on individual agricultural estates, the entire country was divided into districts over the course of the Old Kingdom. The oldest of these is the district of Ma-hedj, which was later counted as the 16th Upper Egyptian district. It is first mentioned in vessel inscriptions found in Djoser’s pyramid complex. However, mentions of further districts only appear in the reign of Sneferu, the founder of the 4th Dynasty. By the end of the Old Kingdom, there were 38 districts, a number that increased to 42 through divisions until Roman times.

Under Djoser, several officials and viziers gained high esteem, foremost among them Imhotep, Hesire, Anch-en-iti, Nedjem-Anch, and Chai-neferu. While Imhotep evidently enjoyed Djoser’s special favor and was even deified later, impressive panels made of valuable cedar wood have been preserved by the official Hesire. Chai-neferu, on the other hand, is only depicted on stone vessels and clay seals.

Expeditions

As the first Egyptian ruler, Djoser organized a state-sponsored expedition to Wadi Maghara in the Sinai Peninsula to exploit the copper and turquoise mines there. A relief commissioned by Djoser in the Wadi depicts him striking a captured Bedouin. Beside him stands a goddess. Behind her is another figure identified by the inscription as the overseer of the desert, Anch-en-iti, who led this expedition. While there is evidence of isolated Egyptian activities in Sinai from predynastic times, centrally organized mine expeditions apparently only became possible through significant advances in administration at the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 3rd Dynasty.

Introduction of the Gold Name

Under Djoser, the solar cult experienced another upswing, which was simultaneously associated with the increasing importance of the king. Since at least the 1st Dynasty, the connection of the king as the living Horus under the sun in the epithet Nebu has been evident, but it was only Djoser who elevated the king’s status as the living Horus on earth to be equal to the sun. These parallels were also evident in pyramid construction, which, from Djoser onwards, assumed ever greater dimensions. His new construction of the step pyramid clearly illustrates the new royal philosophy, as the new architectural style was intended to provide an optical form for eternity and to erect an enduring monument to the king, symbolizing his equal status with the sun. Additionally, Djoser had his tomb directly built within his pyramid and, complementarily, relocated his dummy tomb from Abydos to Saqqara.

Another indication of the expanded solar cult is the first stone-built dummy tomb (South Tomb), which replaced the usual mat construction of wood and metal. Overall, the burial complex underwent a much greater expansion through the changes compared to traditional construction methods. Egyptologists Jochem Kahl, Steven Quirke, and Wolfgang Helck point out the connection to Djoser’s introduction of the Gold Horus Name, which did not elevate the sun above the king and deify it as an independent god but made particularly clear the new and stronger fusion of the king with the sun.

Kahl and Quirke assume that during the introduction of the Gold Horus Name, the intellectual and religious thinking of Djoser’s time underwent a strong change and must have influenced future generations, as succeeding rulers immediately adopted the Gold Horus Name (compare Khasekhemwy).

Building Activity

Saqqara

The Djoser Pyramid

The Djoser Pyramid is the second oldest surviving monumental structure in Egypt built from hewn stones. With its construction, Djoser initiated the era of pyramids in Egypt. It was built in six construction stages, with its appearance being significantly altered multiple times. Originally planned as an 8-meter high mastaba, it was initially expanded twice in length and width. In three further construction stages, it was later transformed first into a four-step and finally into a six-step pyramid with a base measurement of 121 m × 109 m and a height of 62 m.

The burial chamber was constructed in the bedrock beneath the center of the step pyramid. Because of the original design of the pyramid as a flat mastaba, a vertical shaft extends above the burial chamber, intended as an entrance. After the building’s conversion, this function was taken over by two inclined shafts accessible from the north side of the pyramid. From the burial chamber, passages extend in all four directions, all leading into complex gallery systems. Parts of the complex are adorned with faience tiles and relief representations of the king.

Regardless of this, there are still eleven shafts on the east side of the pyramid, which initially descend vertically and then lead horizontally under the pyramid. The five northern shafts served as tombs for Djoser’s family members, but they were already plundered in antiquity. The other six shafts are storage rooms. Ceramic and stone vessels from the graves of almost all the kings of the 1st and 2nd Dynasties, as well as from official tombs of these periods, were found in them.

Around the pyramid extends a vast complex, which is the largest of all Egyptian pyramids. Attached to the north side of the pyramid is the mortuary temple. This consists of two open courts and several rooms, the exact function of which is not entirely clear, as the temple’s design deviates significantly from the later customary mortuary temples. East of the temple is the serdab, where a statue of Djoser was placed, which is now located in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The area east of the pyramid is densely built. Immediately adjacent to the serdab are two buildings known as the North and South Pavilions, the function of which is not entirely clear. They are probably symbolic administrative buildings for Upper and Lower Egypt. Southeast of the pyramid is the Sed Festival Court, which is flanked on its west side by 13 large and on its east side by twelve small chapels, which are symbolic solid structures without actual interior rooms. North of the 13 large chapels is another building known as Temple “T,” which likely played a role in the Sed festival. In the southeast corner of the complex there is a broad entrance colonnade.

The largest part of the southern side of the pyramid is occupied by an open court. This southern court has only two B-shaped structures as its only construction, interpreted as milestones for the symbolic course of the king during the Sed festival. In the southwest corner of the court is the so-called South Tomb, which is somewhat of a reduced version of the burial complex under the pyramid. Its decoration also resembles that of the main complex. This structure could have been intended as a provisional tomb for Djoser, but also as a symbolic tomb for his ka.

The entire west of the complex is occupied by the so-called West Enclosures, under which are long corridors and over 400 chambers. It is still unclear whether these are storage rooms, tombs for Djoser’s servants, a usurped tomb of an earlier king, or the original design for Djoser’s tomb.

The area north of the pyramid is occupied by an open court that has not yet been fully examined. On its north side is an altar and west of this are further galleries, which are storage rooms. In the northwest of the court are several stairway tombs, which are the remnants of an older necropolis overlaid by Djoser’s pyramid complex.

The entire pyramid complex is surrounded by a wall. It has a length of 545 m and a width of 278 m. The wall is executed in the typical style of a palace facade with protrusions and niches and has 14 false doors. The wall itself is surrounded by a monumental trench, which has a width of 40 m and encloses the entire complex in to maximum extent of 750 m.

Private Tombs in Saqqara

Seals with Djoser’s Horus name were found in three private tombs in Saqqara: in Tomb S2305, Tomb S3518, and in the mastaba of Hesire (Tomb S2405).

Beit Khallaf

The necropolis of Beit Khallaf, located north of Abydos, consists of five mastabas, four of which can be dated to Djoser’s reign based on seal finds. The largest of these, Mastaba K1, measures 45 × 85 m and is over 8 m high. Its core masonry consists of several inward-sloping mantles of mudbrick. It may have originally had a niched substructure. A ramp leads to the roof on the east side, where the entrance to the chamber system is located. The stairway has a barrel vault, which is the oldest known vault in Egypt. The underground chamber system replicates the rooms of a house or palace and contains large quantities of ceramic and stone vessels. Due to its size and the seals found, the mastaba was originally thought to be Djoser’s tomb. However, since seals with the name of Queen Nimmaathapi were also found, it seems likely that it is her tomb. The significantly smaller Mastabas K3, K4, and K5, where seals with Djoser’s name were also found, seem to be the tombs of less significant members of Nimmaathapi’s family.

Elephantine

The exact extent of Djoser’s activities on Elephantine Island remains unclear. So far, he is only attested to contemporaneously by several seal impressions, which, on their own, do not constitute direct evidence of construction activities. However, the Famine Stele, created in Ptolemaic times, mentions a temple of Khnum, which could have been founded by Djoser on Elephantine or a neighboring island (such as Sehel or Philae).

Gebelein

The dating of several relief blocks from the Temple of Hathor in Gebelein is uncertain. The blocks are made of limestone and are now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and the Museo Egizio in Turin. They depict, among other things, the image of a king. However, since there is no mention of a name, they can only be stylistically dated to the end of the 2nd or the beginning of the 3rd Dynasty. William Stevenson Smith believed them to be works from Djoser’s time, while Toby Wilkinson tends to favor his predecessor, Khasekhemwy.

Heliopolis

The remains of a small structure are preserved in Heliopolis. They were discovered in the foundation of a subsequent building at the beginning of the 20th century by Ernesto Schiaparelli. It consists of 36 fragments of a small chapel, which was probably built for Djoser’s Sed festival and served to house a cult statue of the king. The exact appearance of the chapel cannot be reconstructed from the remaining fragments. The fragments are now housed in the Museo Egizio in Turin. One piece shows a palace facade and part of Djoser’s Horus name; a second piece depicts the upper part of a representation of the seated king with a wig, ceremonial beard, and Sed festival mantle. A third piece shows the lower part of another representation of the seated king. At his feet kneel three women, identified as Queen Hetephernebti, Princess Inetkaes, and an unknown person.

Special Finds

Royal Sculpture

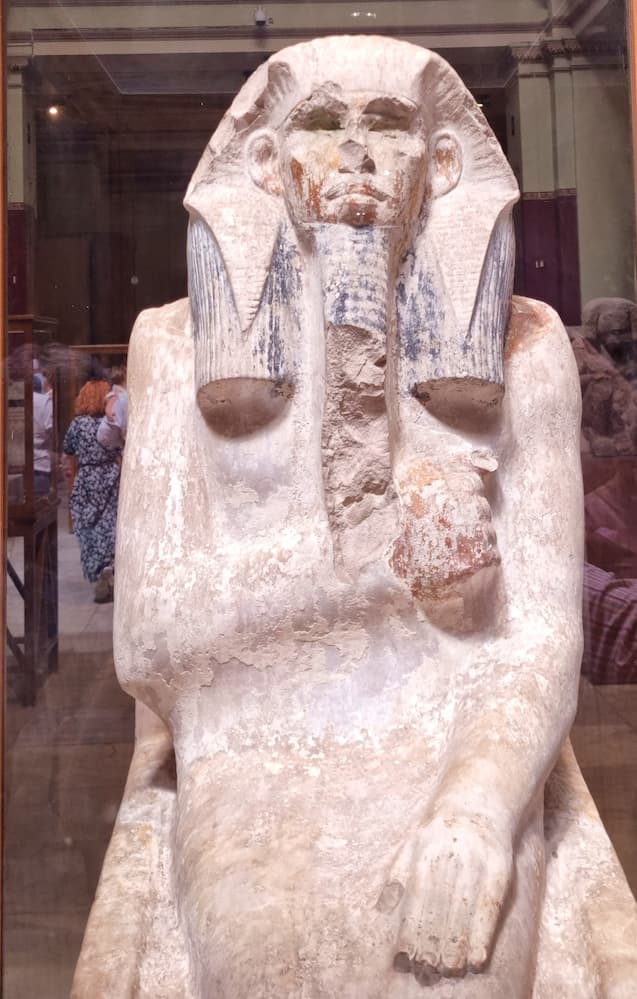

Undoubtedly the most famous artwork from Djoser’s era is his life-sized seated limestone statue, originating from the serdab of Djoser’s complex in Saqqara. Discovered around 1924 by Cecil Mallaby Firth, this masterpiece is made of polished limestone. The pharaoh wears a tight-fitting Hebsed garment and a pleated Nemes headdress over a long stepped wig. Additionally, his chin is adorned with a robust pharaonic beard. Originally, the hands and face were painted brown-red, with the upper and lower eye areas decorated with dark paint. The eye sockets were once painted on their inner sides and adorned with crystal stones – however, these crystals were stolen when the statue was discovered, and the statue was heavily damaged. The original statue is now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (Inv. No. JE 49156), while a replica is displayed in the serdab. During the reconstruction, one of the serdab’s side stones was replaced with a window to allow visitors to see inside the serdab.

Another statue (Inv. No. JE 49889 and 49889a–g) is also located in Cairo, of which only the base with the king’s feet has been preserved. It was also discovered during Firth’s excavations in Djoser’s pyramid complex. Made of limestone, it shows traces of paint. The piece once depicted Djoser as larger than life. With his feet, he crushes nine bows, symbolizing the foreign peoples understood as enemies of Egypt. In front of his feet are three rechit birds, representing hostile peoples in the Nile Delta. The front of the statue’s base bears the name and titulature of the king, along with an inscription with the name Imhotep.

A third piece (Inv. No. JE 60487), also in Cairo, is the remains of a limestone standing statue of the king. Only the torso and remnants of the legs are preserved. The king is depicted not in a striding position but with closed legs, wearing a belt with Hathor ribbons around the hips.

Only the base and feet of a statue group have been preserved. Made of limestone, the piece has a height of 13 cm, a width of 183 cm, and a depth of 42 cm. On the base, there are a total of four pairs of feet, with the two right pairs significantly smaller than the left.

Fragments of statues resembling the serdab statue were found in the area of the mortuary temple, indicating the possible existence of a second serdab.

Additional Statues

A statue, now housed in the Brooklyn Museum (Inv. No. 58.192), possibly originated from Djoser’s pyramid complex. It is a small figure representing a male deity, perhaps Onuris. The piece is made of anorthositic gneiss and has a preserved height of 21.4 cm, a width of 9.7 cm, and a depth of 8.9 cm. It depicts a figure preserved only from the thighs upwards with a wide, rounded backplate. The god is depicted in a standing position with his left leg placed forward, wearing a belt and a phallus pouch around the hips. The arms are held at the sides of the body, with the left hand clenched into a fist and the right hand holding a knife. The god wears a ceremonial beard reaching to the chest and a voluminous round wig.

The Museum of Art and History in Brussels houses a very similar figure (Inv. No. E 7039). This piece, also of uncertain origin, strongly resembles the Brooklyn piece in material and execution. It is also made of gneiss and likely originally stood about 30 cm tall. Only the head with a short wig and the upper part of a rounded back pillar are preserved. The facial features are minimally carved, with the chin area broken off.

In addition to deity figures, there are several prisoner heads from Djoser’s reign, which likely served as thrones or statue bases. Two of these pieces are located in Cairo. The first (Inv. No. JE 49613) is made of granite and measures 25 cm in height, 45 cm in width, and 20 cm in depth. Originally consisting of three heads, only two are now preserved. The right one depicts a Libyan, while the left one depicts an Asiatic. The lost head likely represented a Nubian. The second piece in Cairo (preliminary Inv. No. 18.2.26.5) is made of slate and depicts two heads.

Of unknown origin is a third piece, now housed in the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich. It can only be stylistically attributed to the 3rd Dynasty, most likely Djoser’s reign. It is a block of alabaster measuring 19.5 cm in height, 35 cm in width, and 23 cm in depth. On two adjacent sides, two heads of foreign enemies are depicted. One pair represents Asiatics, while the other represents Libyans.

Djoser in the Memory of Ancient Egypt

Both Djoser and his confidant Imhotep were revered and even deified in later times. Djoser’s name appears on countless objects and in legends from later periods.

Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period

From the 12th Dynasty comes a statue commissioned by Sesostris II in honor of Djoser. Made of diorite, it is housed in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Only the lower half of the statue is preserved. It is a seated figure showing Djoser on a throne. He wears a kilt and has his right hand clenched into a fist resting on his thigh. His feet are supernaturally large, typical of the Middle Kingdom style, and he crushes nine bows symbolizing Egypt’s enemies. The origin of the piece is unknown, but its size, material, and style suggest Thebes. Possibly, the original location was the temple of Karnak, where Sesostris I already erected statues for Sahure and Niuserre, two kings of the 5th Dynasty.

Djoser is also one of the main characters in the famous Westcar Papyrus, mostly dated to the Middle Kingdom or the Second Intermediate Period (13th Dynasty). It contains wonders and tales from the reigns of the pharaohs Djoser, Nebka, Snofru, and Cheops. The story about Djoser is only preserved as the final sentence, with the name of the hero figure (presumably Imhotep) lost.

New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period

During the New Kingdom, in the 18th Dynasty under Thutmose III, the so-called Karnak King List was erected in the Karnak Temple in Thebes, where Djoser’s name was presumably mentioned. Unlike other ancient Egyptian king lists, this is not a complete list of all rulers but a selection list that only mentions those kings for whom offerings were made during the reign of Thutmose III. Djoser’s signature itself is not preserved. The list begins with a destroyed entry and then continues with Sneferu, the founder of the 4th Dynasty. Although the first entry was partially read as Neferkare, this is based on a faulty interpretation by Karl Richard Lepsius. Since the Karnak list is based on a series of statues that were placed in the temple during the 12th Dynasty and a statue from this period is known for Djoser, which probably came from Karnak, it is quite likely that the first entry on the list was dedicated to Djoser.

From the New Kingdom, a total of eleven visitor inscriptions from private individuals in the North and South Houses of the Djoser Pyramid are preserved. The oldest inscription dates from the reign of Amenhotep I (18th Dynasty), while the youngest precisely datable one comes from the reign of Ramesses II (19th Dynasty). In one of the inscriptions, a scribe complains about numerous insubstantial texts left by other people before him. Also, from the Chendjer Pyramid, located south of the Djoser Pyramid, a visitor inscription from the time of Ramesses II is known. It is of particular interest because it refers to Djoser as the inventor of stone construction.

In addition to the visitor inscriptions, a restoration inscription from the 19th Dynasty is also known, which was found on some blocks that originally belonged to the cladding of the Djoser Pyramid. It shows that Chaemwaset, a son of Ramesses II, carried out restoration work on the Djoser Pyramid, as he did on numerous other buildings of the Old Kingdom.

Also from the New Kingdom is a relief fragment from the tomb of the priest Mehu from Saqqara, which dates to the 19th or 20th Dynasty. It depicts three deities facing a series of deceased kings. These are Djoser and Djoserteti from the 3rd Dynasty, as well as Userkaf from the 5th Dynasty. Only a heavily damaged cartouche remains of a fourth king, which has been read partly as Djedkare but occasionally also as Shepseskare. The relief expresses the personal piety of the tomb owner, who had the ancient kings pray to the gods for him.

From the Serapeum in Saqqara, a stele is known that dates to the 22nd to 24th Dynasty. It depicts a king in a praying gesture, identified by an inscription as Djoser. The owner of the stele, a certain Padi-Webastet, addresses a prayer to Osiris-Apis in an inscription and lets Djoser act as an intermediary between himself and the god.

Late Period

In addition to the New Kingdom visitor inscriptions, one was also discovered in the North House of the Djoser Pyramid from the Late Period. It dates to the 26th Dynasty and does not directly reference Djoser, but it proves that his pyramid complex remained open to visitors even at that time.

From the same period, several fragments of stelae and reliefs of Djoser were found in Horbeit and Tanis. Originally dated to the 3rd Dynasty, they have now been identified as Saite copies of works from the Old Kingdom. The style of the reliefs is thus merely a tribute to Djoser’s era.

From the Persian period comes the statue of the priest Jahmes (Berlin Egyptian Museum, Inv. No. 14 765), whose pedestal reads that he had performed the funerary service for the rulers Djoser and Sekhemkhet.

Also, from the Persian period, an inscription was placed under the rule of Darius I in Wadi Hammamat. In it, the chief architect Chenemibre lists his lineage over 22 generations, although the authenticity of his claims is questionable. He names a chief architect named Rahotep, living under Ramesses II, as his ancestor and attributes to him even greater fame than the chief architect Imhotep, who worked under Djoser.

Ptolemaic and Roman Period

The so-called Famine Stele at Sehel (southwest of Elephantine), a rock relief from the Ptolemaic period, recounts a legend about Djoser, according to which the pharaoh ended a seven-year drought by sacrificing to the god Khnum and appeasing him. By referring back to Djoser, the Ptolemaic rulers sought to legitimize an ancient claim to the borderland between Egypt and Nubia (Dodekaschoinos).

Furthermore, from the Ptolemaic period, the coffin of a priest named Senebef is preserved (Berlin Egyptian Museum, Inv. No. 34). An inscription reveals that Senebef served as a funerary priest for Djoser.

Dating to the 1st or 2nd century AD is a demotic papyrus, now held in the Egyptian Institute of the University of Copenhagen. Due to the poor condition of the papyrus, the fictional narrative recorded on it is only partially preserved. It tells of a campaign against Assyria undertaken by Djoser together with Imhotep. The Assyrians are led by a queen, not named, who possesses magical powers. When the Egyptian army eventually camps in Nineveh, Djoser instructs Imhotep to bring the divine images from the fortress of Arbela, as they are to be taken to Egypt. However, a chambermaid appears to him in a dream and warns him against it. The rest of the text is only fragmentarily preserved. It can still be reconstructed that Djoser wants to celebrate his victory in Memphis. Imhotep’s daughter is supposed to perform as a singer, but she refuses. There is also a passage where Imhotep and the Assyrian queen create and animate divine images and make them fight each other. The text bears great similarities to older works of Egyptian literature, like the Westcar Papyrus but also to the Greek Alexander Romance.

Modern Reception

The life of Djoser and his architect Imhotep has been incorporated into numerous fictional works. For example, the Frenchman Pierre Montlaur wrote the novel “Imhotep, le mage du Nil” in 1985 (“Imhotep: Physician of the Pharaohs”). The German author Harald Braem published the novel “Hem-On, der Ägypter” in 1990, set at Djoser’s court. The French writer Bernard Simonay published a historical novel trilogy titled “La première pyramide” (“The First Pyramid”) between 1996 and 1998, covering the life of Djoser.

An asteroid belt discovered in 1960 bears Djoser’s name in outdated (4907) Zoser.