Ancient Egypt’s economy was based on a system of storage and redistribution of goods under the supervision of local administration. The administration, accountable to the ruler, managed the economy, overseeing the collection and storage of goods produced across the country, acquiring foreign products, and distributing them according to the state’s needs. Over time, temples also developed significant infrastructure for storage and redistribution, but these institutions were always linked to the palace, forming an integral part of it and thus maintaining control over the flow of goods in the hands of central authority.

Overview

During the Late Period, due to the increased influence of both the Persian Empire and the Empire of Alexander the Great, within which Egypt was also situated, the role of trade exchange grew. With the expanded trade contacts of the Egyptian state, the use of currency also increased.

Under Persian rule, Egypt became more integrated with the contemporary world, continuing the socio-economic changes initiated during the Ramesside period, leading to greater interactions with Mediterranean basin countries.

During the Ptolemaic period, a network of trade routes was developed. One of the major successes of this period was the reconstruction of the route connecting the Nile to the ports on the Red Sea, made possible by the efforts of Ptolemy II.

Since agriculture was the basis of the economy at the time, the level of the Nile was one of the key factors influencing the economic cycle of ancient Egypt. The annual inundation levels of the Nile varied, influenced by longer climatic cycles, periodically affecting agricultural production. Therefore, administrative centers, belonging to both the ruler and the temples, played an important role in securing the state during dry periods. It was not a monolithic system but a comprehensive network of autonomous administrative units responsible for revenue collection, wage distribution, and the storage and distribution of crops.

The state of this type of economy in different regions depended on the resources provided by the land. Egypt was in a favorable position due to its very fertile agricultural lands along the Nile (the country’s name, Kemet, means “black land”), mild climate, abundance of flora and fauna, and the wealth of rock and mineral resources in the mountains on both sides of the river. Missing resources, such as wood, silver, and incense necessary for rituals, were imported from other countries from the very beginning.

Natural resources

Stone extraction: pink granite in the Aswan area, sandstone in Gebel el-Silsila, shales and breccias in Wadi Hammamat, porphyries in Gebel Duchan, alabaster in Hat-Nub, limestones in Tura and Maasara, pink quartzite in Gebel el-Ahmar, basalts and dolerites in Abuzabal.

Decorative stones: turquoise, malachite, garnet, green feldspar, and chalcedony in the Sinai Peninsula; quartz, calcite, and green feldspar; onyx, amethyst, green beryl, and chalcedony in the eastern desert; amethyst and quartz in the Aswan area; quartz, calcite in the Asyut area, and chalcedony in the Abu Simbel area and the Baharija Oasis; while the Red Sea provided corals and pearls.

Lapis lazuli was most likely imported from Afghanistan, while gold came from Nubia.

Agriculture

Agriculture in all its forms—cultivation, animal husbandry, hunting, and fishing—developed both in the depths of the valley and on the edges of the black soil, and the lands were very easy to exploit.

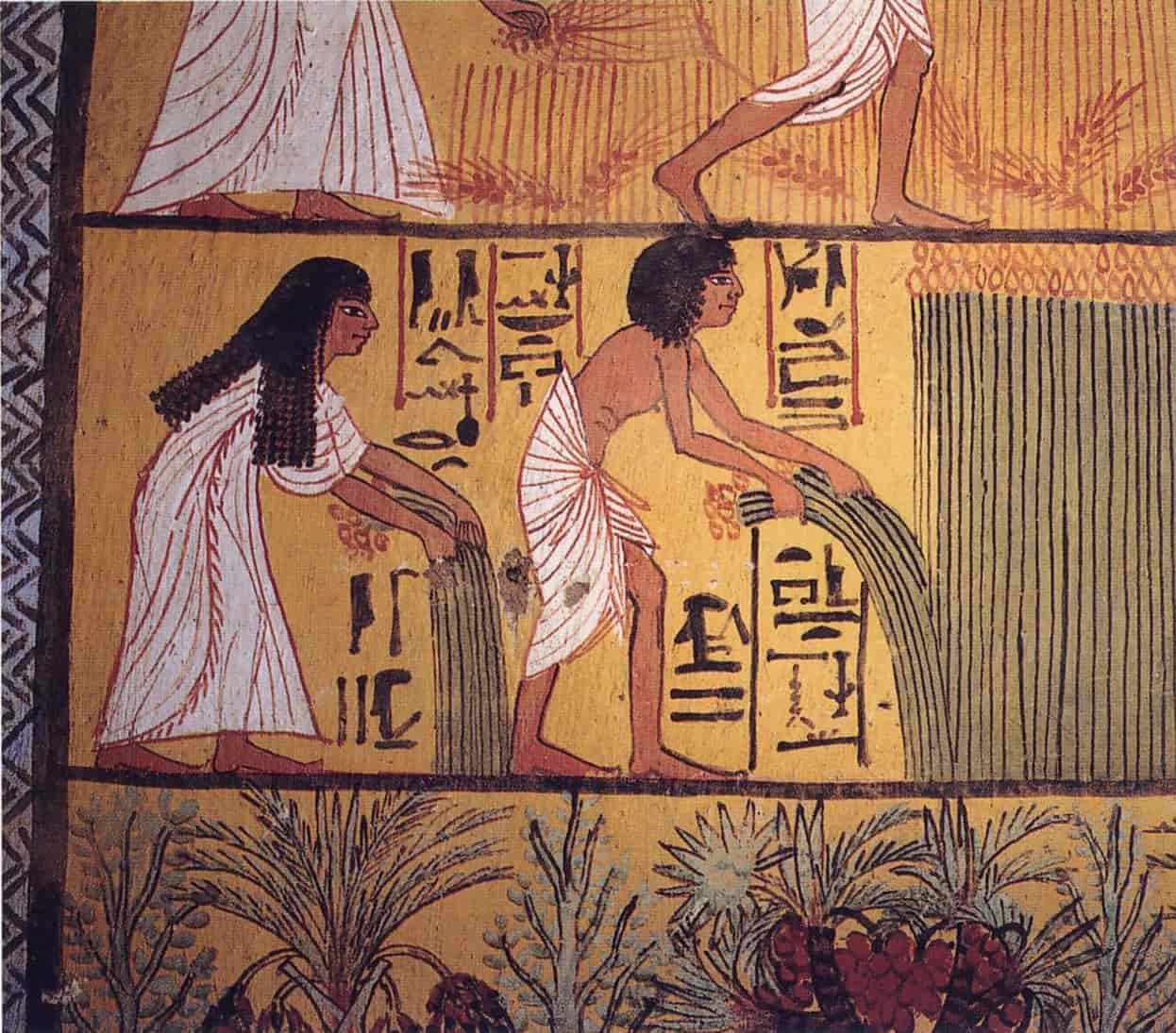

There are many examples of preserved paintings, reliefs, sculptures, and documents from which one can learn exactly how the process of cultivation and animal husbandry proceeded.

Crops depended on the floods of the Nile. The ancient Egyptians distinguished three seasons of the calendar: the flooding of the Nile (Akhet), the growth of plants (Peret), and the harvest (Shemu).

The flood season of the Nile lasted from June to September, when the riverbanks were deposited with mud rich in mineral nutrients.

When the water receded, the vegetative period followed, which lasted from October to February. During this time, farmers plowed the land, planted seeds, and maintained irrigation through a system of ditches and channels.

The canal system developed due to low rainfall, prompting Egyptian farmers to rely on the waters of the Nile. The area where the land was cultivated in the valley during the flood was to some extent leveled, and irrigation canals created a series of large basins, dividing the land designated for irrigation into terraces descending towards the Nile channel. From March to May, the crops were harvested; farmers used sickles and flails to separate the chaff from the grain.

Agricultural produce was processed, for example, ground into flour, or stored in warehouses for later use. From archaeological sources, it appears that in ancient Egypt, cereal crops were grown, including emmer wheat for bread baking and barley for beer brewing; common wheat likely appeared only during the Greco-Roman period. In addition to cereals, legumes were grown, including lentils, chickpeas, and sesame; vegetables—lettuce, onions, and garlic; fruits—especially dates and grapes; as well as fodder crops for animal feed. Beekeeping was also practiced, and papyrus reeds growing on the riverbanks were used to make papyrus, mats, boats, and other items.

Preserved paintings and documents depict the diversity of animal types raised; these definitely included cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, ducks, geese, and most likely pigeons. Chickens were only known from the New Kingdom period onward.

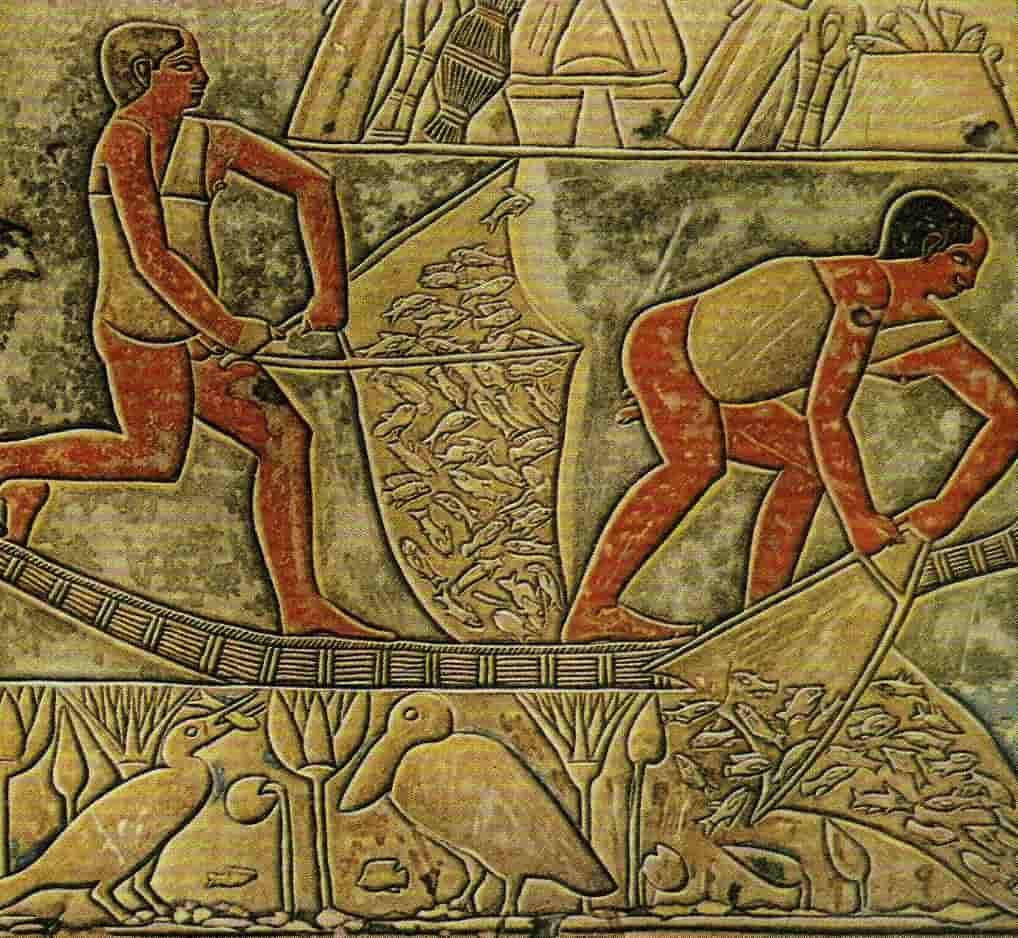

The role of hunting wild mammals in the Egyptian economy was limited, and hunting became a sport for the aristocracy quite early on. However, scenes of fishing and hunting wild birds seem closely related to cattle farming. Representations show, for example, people in the bushes engaged in fishing or cutting papyrus. The final stage of fishing often had to be done using nets, special baskets, or handheld nets. There are also depictions of hippopotamus hunting, which was most likely a necessity rather than a sport.

Craftsmanship

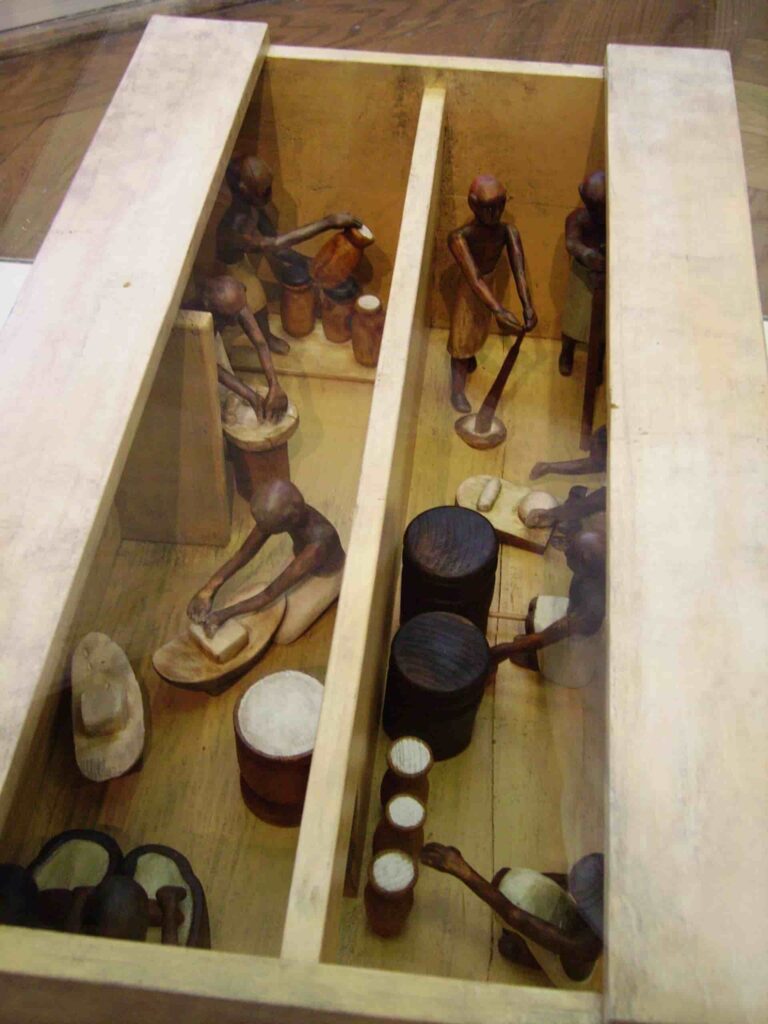

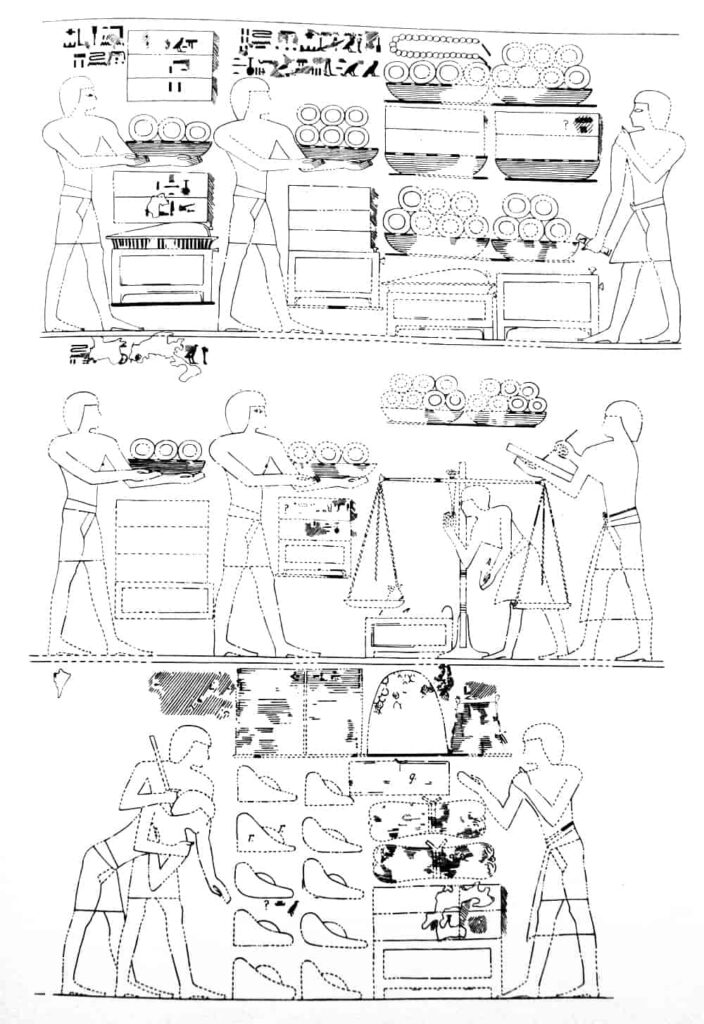

Craftsmanship also played a significant role in the economy of ancient Egypt. In archaeological sources, both in tomb reliefs and paintings, as well as in models, one can see the diversity of professions and the specialization of various groups of craftsmen: carpenters, goldsmiths, jewelers, builders, sculptors (sculpture was treated as both a craft and art), tanners, potters, makers of stone vessels, rope makers, bricklayers, weavers, bakers, cooks, butchers, and brewers.

In addition to producing for the needs of their own farms, specialized workshops were established, producing goods for the state and wealthy landowners.

Trade Expeditions

Egypt undertook trade expeditions to other states in the Mediterranean basin, the Near East, Asia, and some African countries. From the Levant, wood was imported, which was extremely necessary, among other things, for building all types of ships, whose great value was based on Egypt’s geographical location: the main internal communication route was the Nile, and the most common route in foreign expeditions was the sea routes.

Because of this resource, from the very beginning of the Old Kingdom, it was important to have the greatest possible access to the Mediterranean coast to enable uninterrupted supply chains. Since the Middle Kingdom, other items and resources were also exported, such as silver or clay vessels of Mediterranean cultures (e.g., Minoan vessels) or lapis lazuli.

In trade relations with Nubia, gold played the most important role. Gold supplies reached Egypt from the beginnings of the Old Kingdom, with a tremendous increase during the Middle Kingdom and a decline in the middle of the New Kingdom. It was mined later, even during the Roman period, when the exploitation was taken over by the Romans. During the Middle Kingdom, trade with Nubia was centralized in one place, in the town of Mirgissa, allowing the state to oversee trade transactions and most likely collect fees. Besides gold, ostrich feathers, ebony, precious metals, and ivory were also imported from Nubia.

Trade expeditions also reached the coasts of the ancient land of Punt (the region of the Gulf of Aden or the southern coast of the Red Sea). The most famous expedition, led by Queen Hatshepsut, was immortalized in her temple at Deir el-Bahari. Perfumes, myrrh, incense, cinnamon, balsam trees, ebony, ivory, panther skins, and live animals, including baboons, were brought back at that time.

In exchange for luxury goods and raw materials, the Egyptians supplied their neighbors with golden, silver, hard stone, and alabaster vessels, various linen products, papyrus scrolls, ox hides, ropes, lentils, dried fish, scarabs, colorful faience, and artistic furniture.

Taxes

Until the first millennium BCE, taxes were paid in the form of grain, cattle, and other goods, as well as in the form of corvée labor. During the Old Kingdom, goods and services were valued using a metal measure (copper, silver, or gold). In economic documents, references to such a value measure always appear because it was used to determine the price in product exchanges. However, in the case of larger trade transactions, the value measure was often given in metal.

There is evidence that gold and silver were also used in the tax system (alongside other goods) when villages and towns were taxpayers, and gold most often appears in texts related to officials located at the southern border of the state. However, taxes in the form of “money” were not known until the Third Intermediate Period.

After the unification of the predynastic states of Upper and Lower Egypt around 3100 BCE, a state tax system was initiated to support the ruler and his court. The office was located in Memphis, which became the seat of the social elite and the main institutions of the Old Kingdom.

The royal treasury was under the supervision of the royal steward, who controlled the collection, storage, processing, and distribution of state revenues. This office had its roots in the Predynastic Period, when both kingdoms competed with each other. As a result, the organization of this system in the Old Kingdom was a two-chamber office.

Such a system reflected the geographical, social, and economic differences of both areas, increasing its efficiency. Products from Egyptian fields were sent to the warehouse, where they awaited redistribution. Due to the close connection between state and local offices, donations for cult and tomb temples were also stored in royal warehouses. The state treasury redistributed revenues in kind to those dependent on the ruler and the temples under its authority.

During the Middle Kingdom, the system looked similar, but preserved documents indicate that many peasants refused corvée labor, i.e., cultivation of fields, maintenance and repair of irrigation channels, work on construction projects, or acquisition of resources abroad.

In the New Kingdom period, the importance of priests from the great temples, especially the temples of Amun Ra and Ptah, increased. Despite gaining significant economic independence through their own assets, temples also enriched themselves by continuously supplying them through state organs. Fiscal documents concerning the levy in the form of offerings on altars, animals for sacrifice, clothing for temple statues, and various other needs for cults mainly come from temples, whereas documents showing the state’s side have not been preserved. Therefore, it is not possible to verify the existence of a central tax collection system, despite the existence of the “Master of Taxes” office.

However, it is known that garrisons were maintained by tax revenues. Revenue from taxes also depended on the extraction of stone for construction projects and the wages of workers in the royal necropolis, located in the village of Deir el-Medina.

In the Third Intermediate Period, taxes continued to be collected in the form of grain and corvée labor for the state. The main change during this period was the use of silver as a means of payment instead of the unit of value used so far. However, the monetization of the tax system remains the domain of later rulers, from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

Currency and Prices

During the time of the pharaohs, trade in Egypt was based on a barter system. Agricultural products could be exchanged for craft products, houses, or slaves, and one could even buy a position as a state official. During the Old Kingdom, the concept of value developed, and the abstract price of exchanged items was estimated according to a metal measure (copper, silver, or gold). In economic documents, references to such a value measure always appear because it was used to determine the price in product exchanges. However, in the case of larger trade transactions, the value measure was often given in metal.

The units of exchange during the Old and Middle Kingdoms were garments and debens, while during the XIX dynasty (New Kingdom), a new unit, the kit, also appeared.

- 1 shat weighed 7.5 g of gold

- 1 deben = 12 shat (or 90 g of gold)

- 1 kit = 1/10 of a deben of silver

The decimal system for shat and deben used in the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms up to the XIX dynasty was changed to the decimal system for the kit unit since the XIX dynasty.

Value was expressed in various units corresponding to the quantity of certain products: the weight of silver and copper/bronze (deben or kit), but also units of grain and sesame oil volume (char and oipe for grain, hin for oil), with 1 char of grain being roughly equal to two debens.

In the third millennium BCE, there was a wide range of copper prices relative to silver, and the value of grain relative to silver corresponded to the ideal. Thus, the concept of equivalence was just developing. However, in the second millennium BCE, the range of copper prices sharply decreased, while the value of grain in relation to silver increased.

This may be related to the fact that in the second millennium BCE, prices had to be set due to investments in exports. Exchange was based on price differences, and in this way, market prices determined investments and supply strategy.

According to another hypothesis, the value of silver decreased due to the appearance of a large amount of this metal on the market after a series of tomb robberies.

Reference

- J. Baines, J. Malek, Egypt, World of Books 1996

- S. Katary, Taxation (until the End of the Third Intermediate Period). In Juan Carlos Moreno García, Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles 2011

- J.G. Manning, I. Morris, The Ancient Economy. Evidence and Models, Stanford University Press, 2005

- P.T. Nicholson, Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press 2000

- B.G. Trigger, B.J. Kemp, D. O’Connor, A.B. LLoyd, Ancient Egypt. A social history, Cambridge University Press 1983

- D.A. Warburton, Ancient Egypt. A Monolithic State in a Polytheistic Market Economy, IBAES VII, 2007