This is the story of the First Battle of Bull Run. In the early stages of the American Civil War, many people on both sides believed that the war would be settled in a single, decisive battle. It was strange that Clausewitz’s competitor, Jomini, who held beliefs diametrically opposed to his own, was then in the odor of holiness in American military colleges, especially West Point, but this was the legacy of the Napoleonic campaigns and their most renowned analyst. As the Confederacy took up defensive positions, the Union actively worked to bring about their inevitable destruction. This First Battle of Bull Run was the first battle of the Civil War to be fought on a large scale.

The North prepared its offensive

Both sides were confident in their ability to defeat the other’s armed forces and ultimately shatter their will to fight. The close proximity of these two capitals contributed to this sense. Soon after Virginia’s independence was announced, the Confederacy chose to relocate its capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, only 100 miles south of Washington. By the end of May, the decision that was made to both reward Virginia and encourage the other slave states had taken effect.

This installation was a bold assertion of independence and a serious challenge to federal authority, and it understandably stoked tensions in the North. This viewpoint was exacerbated by the fact that the Northern Virginia front had been relatively quiet in the weeks following the seizure of Alexandria, with the exception of a skirmish on June 1 between a patrol of Federal cavalry and a company of Confederate militiamen at Fairfax Court House. The Northern army centered itself on Washington for the following month.

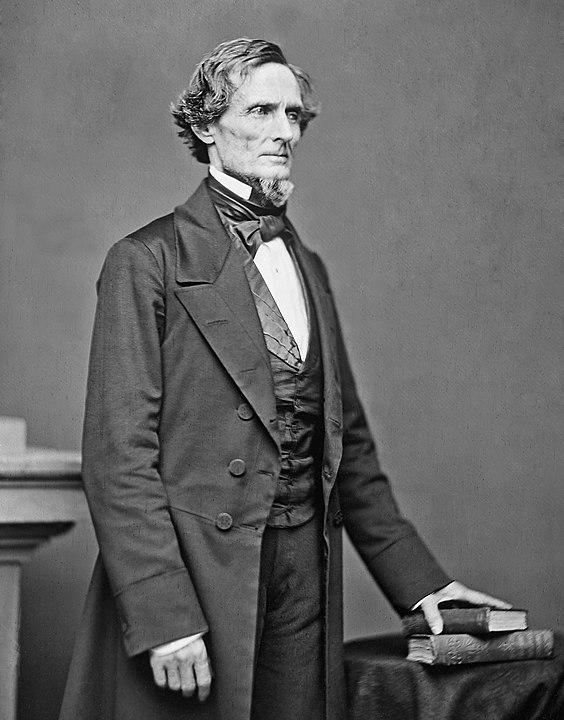

Lincoln summoned Irvin McDowell, a member of the staff, when Robert Lee denied leadership of the Northern army and switched sides. He had never led soldiers in battle but was well regarded as a capable planner and strategist. As an aside, he was Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase’s protege. In a May 14 promotion, McDowell became commandant of the Army of Northeastern Virginia, the greatest military force in North America at the time.

Lincoln expected his new commander’s organizational and training skills to improve the quality and experience of his troops, despite the latter’s low standards. McDowell, sadly, was quickly subjected to public pressure. When it became clear that the third session of the Confederate Provisional Congress would be held in Richmond beginning on July 20, the pressure mounted.

The New York Tribune, the de facto mouthpiece of the Republican Party, published an editorial by Republican Party leader Horace Greeley on June 26 with the headline “On to Richmond!” calling for a march on the Southern capital before July 4. He incited a large media campaign with his impassioned war rhetoric, which ultimately led to the president ordering an offensive. McDowell hesitantly agreed since he believed his troops were unprepared.

Prelude to the battle

Around 35,000 soldiers were serving in the Army of Northeastern Virginia’s five divisions at the start of July 1861. Moreover, there was a second group stationed on the other side of the Potomac. With 18,000 men under arms, the majority of them were Pennsylvanian volunteers and militiamen.

Robert Patterson, the group’s commander and a veteran of the war with Mexico, was a powerful politician in Pennsylvania. As its name suggests, the goal of this “Shenandoah Army” was to seize control of the Shenandoah Valley. Virginia’s agricultural heart was located in the Shenandoah Valley, which also served as a key north-south transportation corridor.

About 12,000 of General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate troops were arrayed against him. With the majority of his army stationed at Winchester, Johnston formed the left wing of the Southern force, leaving only Thomas Jackson’s brigade to guard the south bank of the Potomac. Confederate forces were based in Manassas, a railroad junction where Fort Sumter’s conqueror, Pierre Beauregard, had stationed 20,000 soldiers behind the narrow Bull Run branch to the Potomac.

As a result, he had direct lines of communication with both Johnston on his left and the capital of the Confederacy behind him. Beauregard dispatched an additional three thousand troops, led by Theophilus Holmes, to the landing at the mouth of Aquia Creek, where it meets the Potomac River, to protect his right flank, which he feared would be attacked by amphibious tactics.

According to the Northern Strategy, McDowell and Patterson’s troops needed to work together to achieve victory. The latter was given the mission of protecting Johnston’s forces in the valley while also retaking Harpers Ferry at the junction of the Shenandoah and the Potomac. The clear goal of this action was to stop Johnston from sending reinforcements to Manassas to help Beauregard, allowing McDowell to keep his numerical advantage.

By crossing the Potomac on July 2, Patterson was able to turn the tide of a minor skirmish at Hoke’s Run and drive back the advancing Confederate forces. His march was interrupted the following day, and he did not resume it until July 15, when he leaped south. However, instead of heading south to assault Johnston from Winchester, he veered north to seize Harpers Ferry. He would not move again.

This unexpected meekness gave Johnston time to reorganize his forces and provide the reinforcements Beauregard desperately needed. On the 19th and 20th of July, Johnston withdrew to Strasburg and then sent his entire force across the Manassas Gap Railroad to the battleground of Manassas. There was no longer a numerical advantage for the North, as the majority of the 35,000 Confederate men had gathered at Manassas thanks to Beauregard’s return of Holmes. Johnston, the more experienced officer, was promoted to brigadier general and took charge.

First shots

The Northern attack was hampered by more than just Patterson’s inaction. Specifically, McDowell had made two contributions. The Army of Northeastern Virginia didn’t start moving south until July 16, giving Johnston enough time to reinforce Beauregard. Next, he had depleted his forces even further, assigning Theodore Runyon’s division—his least powerful—to guard his supply route. Accordingly, on the morning of July 18, his army of little more than 30,000 troops reached Centreville (really a tiny village).

6.2 miles (10 kilometers) from Manassas, McDowell ordered Daniel Tyler’s division to scout the area near Centreville. There were no soldiers in town, so Tyler traveled south to Blackburn’s Ford, one of the fords on Bull Run. He sent Israel Richardson’s brigade in, thinking it was lightly protected. To make matters worse, he failed to see James Longstreet’s Confederate brigade, which was holding the ford with great resolve.

Jubal Early’s brigade, which had been in reserve, was promptly sent to assist Longstreet. Unknowingly, Tyler actually sprinted into the bulk of the South’s defenders. The brigade led by Richardson faltered under the onslaught of enemy fire and was forced to flee. The Northern Army returned to Centerville at the conclusion of the day to reorganize.

After two days, it would still be there. After the battle at Blackburn’s Ford and the retreat of Richardson’s brigade, McDowell was hesitant to order a direct assault with his still-nervous troops. Instead, he sought a method to turn the Confederates left. Northern commander, Thaddeus Lowe, who had enlisted himself and his hot-air balloons in the service of the Union due to a severe dearth of cavalry (he only had one ad hoc battalion of regular cavalry) for reconnaissance purposes, called on him. Thanks to his flights, McDowell was able to form a detailed enough picture of the Southern positions to formulate an assault strategy.

The Federals waited cautiously, but their opponents benefited from Johnston’s 12,000 soldiers and Holmes’ 3,000 when they arrived. They quickly converged on Blackburn’s Ford. Beauregard and Johnston, emboldened by their success in the skirmish of July 18, resolved to launch an assault as soon as Edmund Kirby Smith’s brigade, coming from the Shenandoah Valley, arrived. The two soldiers intended to launch a full-scale assault on the northern left wing, cutting off the enemy army’s escape route and ensuring its total destruction.

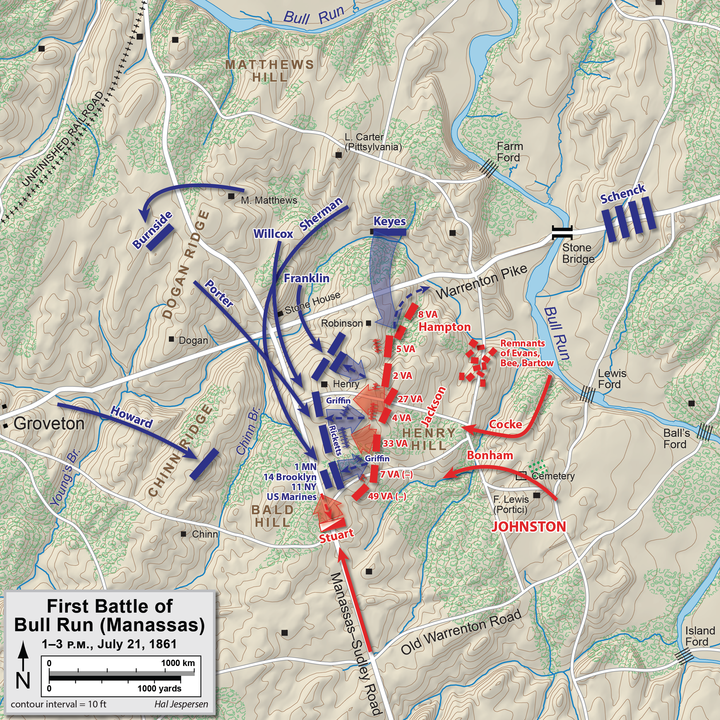

McDowell, for his part, came up with a strategy that was both expansive and intricate. He, too, had his sights set on the enemy’s left flank, planning to withdraw all but the Richardson Brigade from the front of Blackburn’s Ford and rely on Dixon Miles’ division in the area near Centreville. The rest of Tyler’s division would head west to attack the Warrenton Turnpike, specifically the stone bridge across Bull Run. A diversion across Bull Run at the Sudley Springs ford farther west was planned for the final two divisions, commanded by David Hunter and Samuel Heintzelmann.

On the morning of July 21, 1861, the Northeastern Virginia Army left camp. For the 100th anniversary of the fight, historian Bruce Catton has left a vivid and evocative narrative of the coming march in The Coming Fury, the first volume of his Civil War trilogy. He describes how the bad state of the roads leading to Sudley Springs and the indiscipline of the men hindered Hunter and Heintzelmann’s advance. As the sun rose, the heat grew oppressive, and many of the men dispersed into the thicket to forage for blackberries and attempt to cool off. McDowell had obviously come up with a strategy that was beyond the capabilities of his band of Sunday soldiers.

Union strikes first

In the early hours of the morning, at 5:15, the Northern guns fired the first rounds. Within a short time, Tyler had Robert Schenck’s army marching toward the stone bridge. Only a few hundred troops from Nathan Evans’ brigade defended the bridge. Both troops’ front lines deployed as skirmishers and traded fire for a whole hour.

Evans began to think that the enemy’s apparent numerical superiority was a ruse when they were too sluggish to launch a definite attack. As dawn broke, the northern move was noticed by the signal detachment, 8 miles (13 kilometers) distant on the highest point of the battlefield. By semaphore, he alerted Evans, who shifted the majority of his troops to Matthew’s Hill, to the northwest of the bridge.

It took Hunter’s division until 9:30 a.m. to cross the Sudley Springs ford; it took the Federal right wing five hours to travel the same distance. The division launched a surprise attack on Evans’ new positions but was met with intense resistance.

Hunter was wounded in the face and neck, and Ambrose Burnside’s brigade, which was in the lead, lost two colonels—one dead and the other wounded—within a matter of minutes while mounted on their horses. This initial Northern assault was easily repelled because of its lack of preparation. As Burnside’s division fell under his command, Andrew Porter moved his brigade to the right.

The Southerners were certain to strike first. The men under Beauregard’s and Johnston’s command had been waiting since four in the morning for the order to move. There was a lot of uncertainty after the Confederate generals heard the cannonades surrounding the stone bridge and tried to direct limited raids to alleviate pressure on Evans. After learning of the Federal flanking move, Johnston dispatched Barnard Bee’s, Francis Bartow’s, and Jackson’s brigades straight to Evans’ relief.

The first two units arrived at the objective at approximately 10:00 a.m., taking up position to the right of Evans’ soldiers while the latter pushed the Burnside brigade back. Porter fixed things by bringing the disciplined regular infantry unit of Major George Sykes to his aid. Two of Porter’s regiments ran away when they were hit by Confederate fire, and they could only be partially regrouped before Heintzelman’s division helped the Federal troops regain the lead.

An uncertain struggle

Battles on the lower slopes of Matthew’s Hill were particularly violent and cost lives on both sides. The defenders, though, did not back down. Only Tyler’s division could make a difference now because the other two in his right wing were bogged down in a fight they couldn’t win. McDowell gave him orders to cross Bull Run and attack the Confederate position from behind, and Tyler responded by sending two more brigades, led by William Sherman and Erasmus Keyes, to assist.

Sherman decided against trying to force his way across the stone bridge, which was still held by skirmishers and a Confederate gun that was too weak to block the passage but strong enough to cause heavy damage to the assault. Not too long ago, he stumbled upon a hitherto unknown ford connecting Sudley Springs with the stone bridge. This area was, of course, completely unprotected. Sherman led his entire brigade through without resistance, and Keyes soon followed.

Francis Bartow’s two Georgia regiments were caught off guard as Sherman’s brigade attacked from behind. Rep. Bartow had fought hard against the governor of Georgia, who tried to stop his men from leaving for Virginia on the grounds that they should stay behind and defend the Peach State. It was because Bartow had disobeyed the governor that he gained widespread support. His brigade put up a valiant fight, but their situation was hopeless; they were trapped in the middle of the fighting and lost well over half their numbers.

Sherman’s assault, in conjunction with the redoubled attacks of the Northern right flank, was ultimately decisive. The last of the Confederate line broke down at 11:30 a.m. and fled in disarray to the southeast. As the Federals closed in on them, the fugitives made it to Young’s Branch, a minor tributary of Bull Run, and the Warrenton toll road.

The South Carolina Legion, a regiment-sized organization consisting of infantry, cavalry, and artillery created and commanded by rich planter Wade Hampton, was among the independent units dispatched by Johnston to help his cause. With help from Evans’ Louisianan battalion, Bartow’s brigade was able to reorganize and mount a counterattack. On the other hand, they were greatly outnumbered. With Hampton wounded and Bartow dead, their troops fled.

The left flank of the Confederate army appeared to be in imminent danger of collapse, and the situation had become catastrophic. President Davis, who had come from Richmond the moment he learned that the long-awaited conflict was approaching, was seeing a defeat unfold as fugitives piled up in its rear. However, he failed to realize that a similar scene unfolded towards the rear of the Northern force. Both forces at Bull Run were on the point of collapse at the same moment, and it wouldn’t have taken much for victory to fall to either side.

The decisive moment

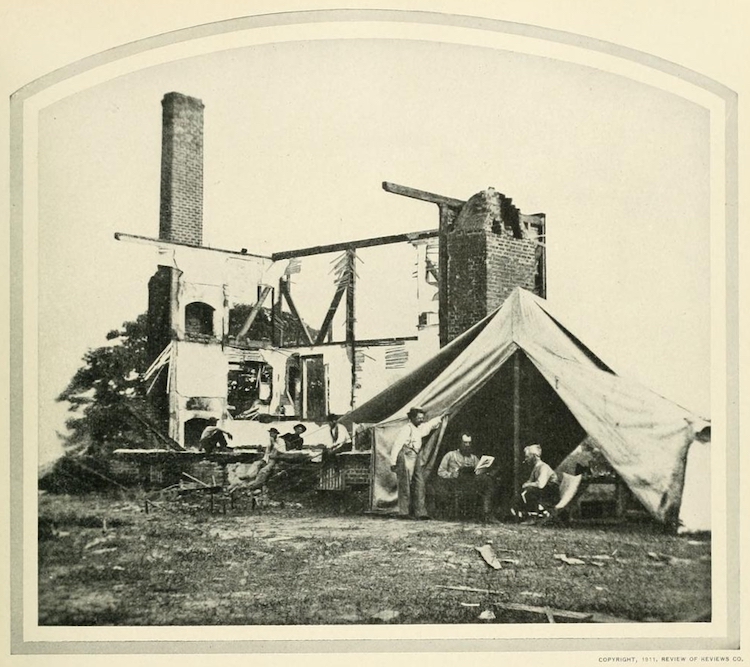

Although ultimately futile, Hampton and Bartow’s counterattack saved the Confederates precious time, allowing Jackson’s Brigade’s five Virginian regiments to position themselves on Henry House Hill to the south of Young’s Branch. Named after a sick, eighty-year-old widow who refused to leave her house before the fight, “Judith Henry’s House” got its moniker because of Henry. Confederate skirmishers were spotted nearby as Federal artillery fired on the building, killing widow Henry.

Despite having the upper hand, McDowell did not immediately attempt to seize Henry House Hill. He was only following the then-current U.S. Army tactics to the letter. During the conflict with Mexico, a new tactic known as “flying artillery” was developed for field guns. This tactic comprised placing the guns in battery as near to the enemy lines as possible in order to shower them with grapeshot, which was significantly more effective than full ball salvos at long range. In contrast, the Mexicans could only make use of their smoothbore rifles, which had a very restricted effective range. Fifteen years later, when faced with other, better-armed Americans, it was a different story.

To counter this, the Northern commander sent troops and artillery forward under Captains Griffin and Ricketts. There was a terrible lack of coordination along the Union lines, and troops from various brigades and divisions were mixed together. Many of the Burnside and Porter brigades’ regiments were up front, while others were abandoned on Matthew’s Hill. They were combined with Heintzelmann’s division, a portion of Keyes’ brigade, the brigades of Orlando Willcox and William Franklin, and others. It was only Sherman’s brigade that was even close to being in working condition, and even then, they were just holding in reserve. There was widespread disarray despite (and perhaps especially because of) the successful Northern push.

The Federal artillery bombardment yielded little result because of the terrain and inadequate cannon placement, allowing the surviving Southern soldiers to reorganize behind Jackson. A famous and widely recounted incident ensued, leading to Jackson being dubbed “Stonewall.” General Bee, attempting to rally his shaken army, said to them, “Look at Jackson standing there like a stonewall!” Rally behind the Virginians!

This sentence may not have been intended as a declaration of awe, despite its common interpretation. Seeing that Jackson reportedly did nothing while Bee was being beaten up on Matthew’s Hill, several of Bee’s officers concluded that their general was merely unhappy with Jackson. Barnard Bee was shot in the chest and died the next day, so he never got the chance to explain himself.

The legend of Stonewall Jackson was formed, but he would later claim that the moniker belonged to his unit and not to himself. Most of the volunteers in 1861 weren’t able to handle the stringent discipline that Jackson expected of his troops. As the disarray in the Northern lines spread, this fixation would be fruitful. Nearing two o’clock in the afternoon, he advanced his troops on the Northern artillery.

One of them was uniformed in blue. The Northern gunners stopped firing when they saw the Virginians approaching out of fear of accidentally killing friendly troops. At close range, the Confederates unleashed a deadly volley that killed most of the servants and drove out the supporting troops, including the 11th New York (Ellsworth’s renowned Fire Zouaves) and the Marine battalion.

It was only because of the timely arrival of James Ewell Brown “J.E.B.” Stuart and the 1st Virginia Cavalry that their retreat turned into a frantic haste. Jackson had ordered the latter to protect his vulnerable left flank, which was defended by a few dispersed troops and the remnants of the Bartow Brigade. When Stuart discovered the retreating New York Zouaves, he thought they were Confederate soldiers, so he assaulted them. Few of his riders followed him, and their charge itself inflicted few losses. But it demoralized the Northerners, who started shouting in fear and spreading false alarms behind them.

From defeat to debacle

Though the tide of fortune had turned, the fight was far from over. The Northern cannons went back and forth multiple times as McDowell tried to reclaim them with a series of counterattacks. However, they were unable to work together because of the chaos on the Federal lines. The North never committed more than two regiments at a time; therefore, Jackson’s brigade was able to successfully repel each attack. By staying united, it ultimately prevailed.

A little after 4 o’clock, Jackson was bolstered by two battalions from Philip Cocke’s brigade, which had been protecting the Lewis Ford to the east. He ordered his bolstered brigade to advance, fit bayonets to their cannons, and charge while “howling like fury.” It was the “rebel cry” that would come to symbolize the Confederate troops in the minds of Northern veterans and live on in their lexicon as a metaphor for terror. During the next attack, both Generals Heintzelmann and Willcox were hurt, and Willcox was captured.

The Federal troops were already exhausted from the approach march and the day of warfare in the sweltering heat, and this was just the final straw. They surrendered and started walking off the field. McDowell’s supply lines were nearly depleted, and Southern reinforcements kept coming. Late in the battle, Early’s brigade, bolstered by portions of Milledge Bonham’s and E.K. Smith’s, and fresh off the train, attacked Oliver Howard’s brigade, the last fresh Northern unit, on Chinn Ridge, a tiny rise west of Henry House Hill. While Smith was injured in the attack, Howard was also unable to maintain his position and was forced to retreat.

When a wagon stopped in the middle of a bridge, blocking the way to Centreville, the Army of Northeastern Virginia’s withdrawal deteriorated into a total rout. As they fled from their powerless superiors, the troops panicked and abandoned their gear. Many of the officers didn’t retake command of their battalions until the next day, when they were already on the outskirts of Washington.

Not only were fugitives clogging the highways, but so were well-to-do citizens of the capital city who had planned to take advantage of the beautiful weather to go watch the Union win. McDowell had instructed Dixon Miles, the division commander, to cover the army’s departure with his remaining men, but Miles had been drinking and had merely added to the chaos.

Bull Run: A Battle with major consequences

Beauregard and Johnston, for their parts, sought to build on their triumph. They sent Longstreet and Bonham to Centreville to obstruct the Union army’s retreat, but the two brigades got entangled on the same road, and Bonham stopped moving when Richardson’s brigade opened up on him with cannon fire. Several hundred of the fleeing Union soldiers were captured by the Confederates. Sherman’s brigade and Sykes’ regulars were able to hold off the following Southern forces.

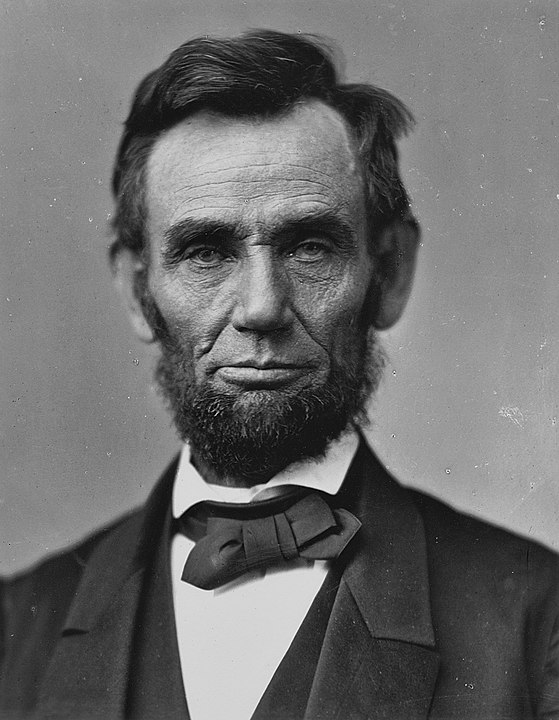

Concern from fleeing soldiers and citizens on the streets of Washington, D.C., reached the White House. Lincoln was concerned that the defenseless capital might fall to a rebel onslaught. No assault materialized, though. Near the end of the conflict, President Davis went to see Jackson, who had suffered a minor wound to his left hand. He demanded an additional five thousand troops and pledged to march on Washington the next day. The Southern Army had taken heavy losses in recent battles, and Davis didn’t have quite the number of troops Jackson requested to launch such an operation.

A total of around 2,000 Confederate soldiers and 3,000 Union soldiers had been killed or injured; the disparity was attributed primarily to captured soldiers. Over the course of the conflict, approximately a thousand soldiers perished. Consequences arose from the Battle of Bull Run, which the South renamed Manassas. Due to the chaos of the combat, both sides made efforts to standardize their attire and flags. Beauregard created the Southern battle flag, which has become a symbol of the South and the Confederacy despite never having been the official flag of either.

There was a major uproar over it at the Northern Command. Lincoln fired General McDowell and replaced him with General George McClellan. Since his triumphs in West Virginia, McClellan had gained widespread support and was now considered crucial to the Union cause. In the next few months, McClellan would call the Army of Northeastern Virginia the Army of the Potomac and do a thorough job of strengthening and reorganizing the army, including getting rid of the less capable leaders. Patterson, who did nothing to help, eventually resigned from the army in late July as a result.

Lincoln, his administration, and Congress all anticipated a drawn-out war. On July 22, the president issued a call for half a million volunteers to serve for three years, and in the weeks that followed, Congress prepared plans for an extensive and protracted war effort. The hope that this battle would be over quickly was gone for both sides. The North realized that it would take a lengthy and expensive war to put down the insurrection, and the South realized that a defensive win alone wouldn’t guarantee its freedom. The Civil War had barely begun, and the bloodiest conflict to that point, the Battle of Bull Run, would not remain such for long.

Bibliography:

- Robertson, James I., Jr. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-02-864685-1.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide.

- Robertson, James I., Jr. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-02-864685-1.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of First Bull Run: An atlas of the First Bull Run (Manassas) Campaign, including the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, June–October 1861. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-60-9.

- Hankinson, Alan. First Bull Run 1861: The South’s First Victory. Osprey Campaign Series #10. London: Osprey Publishing, 1991. ISBN 1-85532-133-5.

- Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.