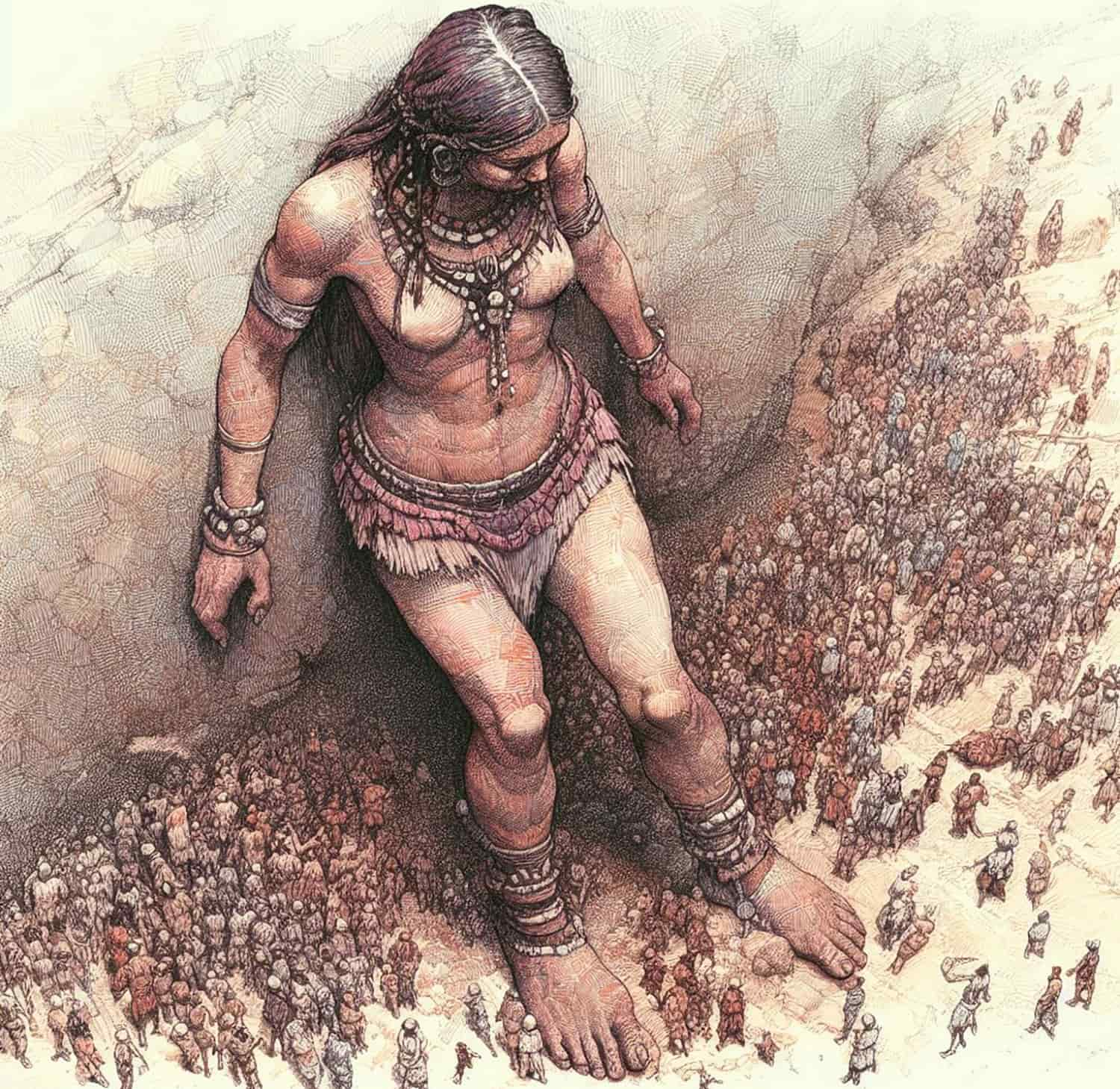

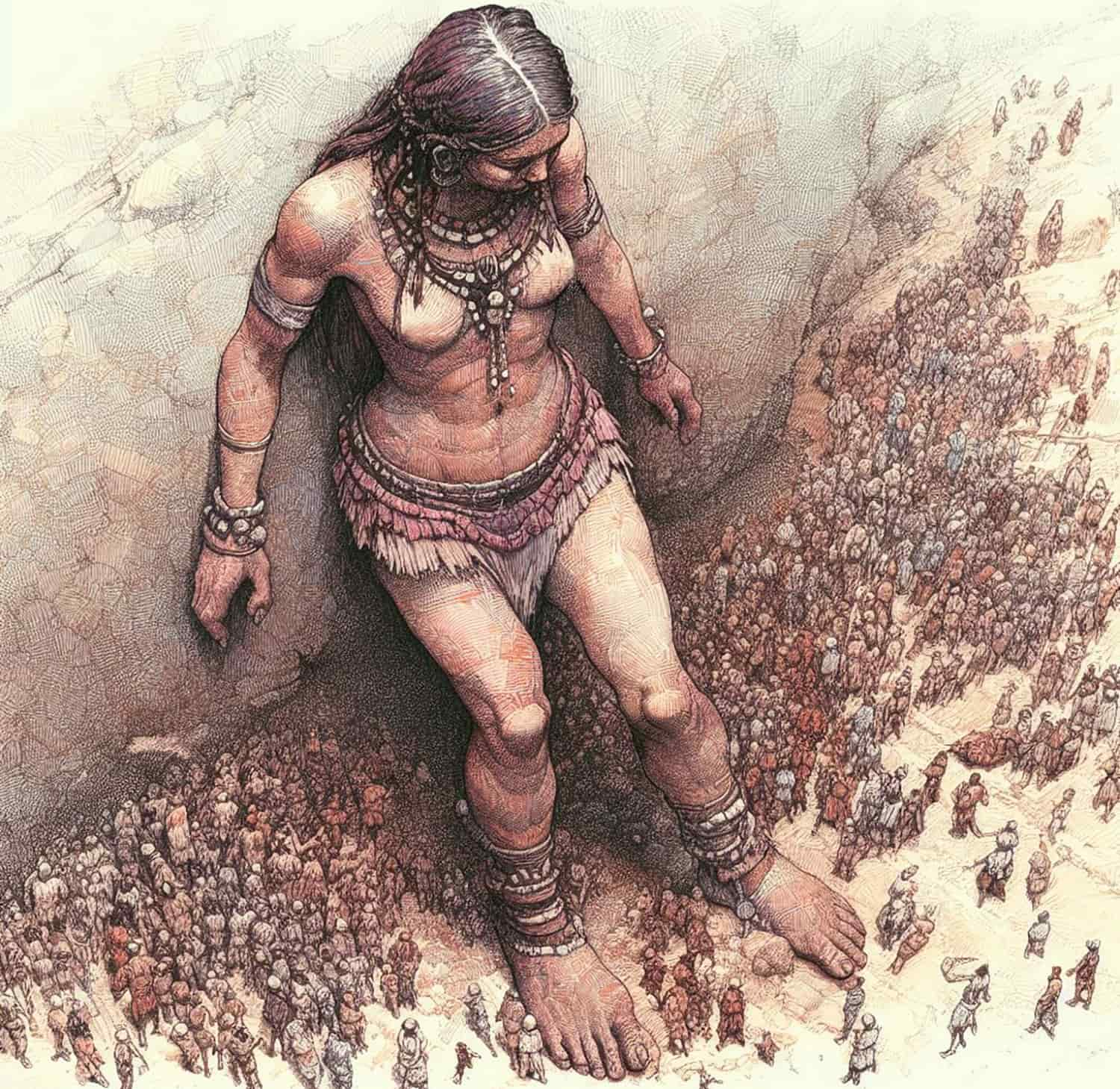

Giantess: History of a Mythological Being

Historically associated with displeasured overtones, the image of giantesses in popular culture has evolved to reflect shifting cultural views on women's assertiveness.

Historically associated with displeasured overtones, the image of giantesses in popular culture has evolved to reflect shifting cultural views on women's assertiveness.