Time was pressing. In March of 717, the new emperor finally used the Golden Gate to enter Constantinople, the capital city he had inherited. But there was hardly any time to celebrate. It was reported that an Arab armada numbering around 1800 ships was battling its way along the shores of Asia Minor. Having already destroyed the Visigoth Kingdom in Spain with the help of his brother and predecessor al-Walid I, Caliph Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik hoped to complete the conquest of eastern Rome with this fleet.

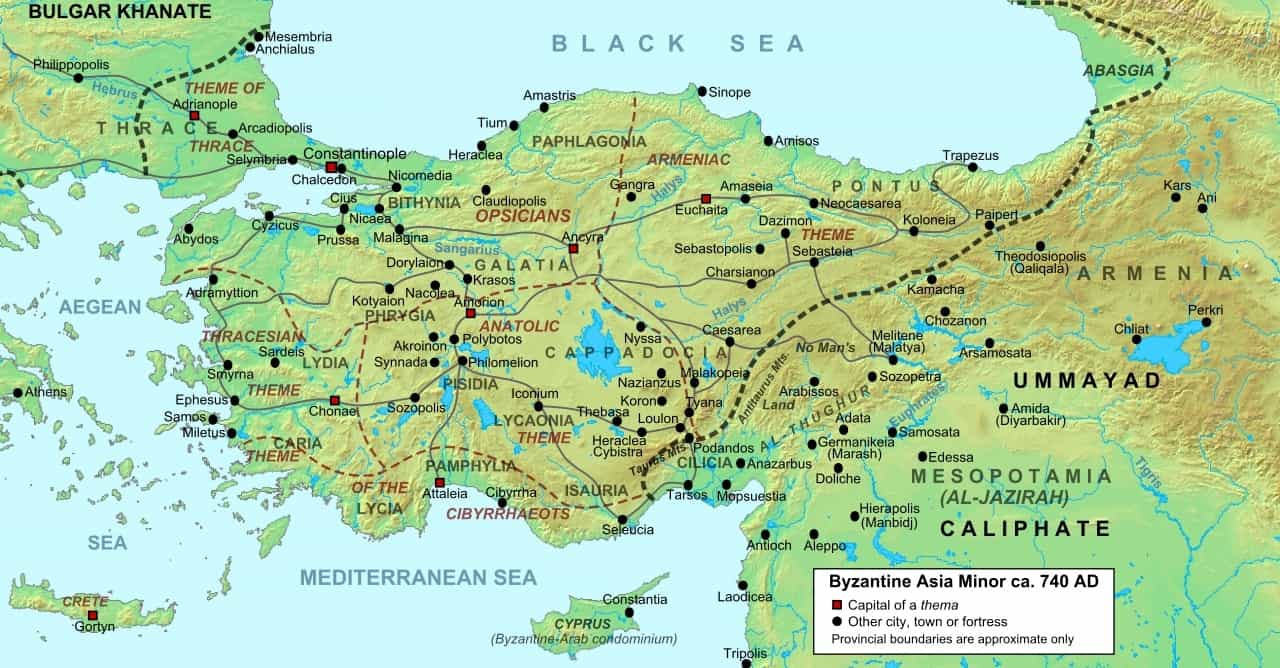

Leo III (ca. 680–741), the new ruler often called the “Isaurian”, did have two aces up his sleeve. Constantinople’s warehouses had been restocked, and the city’s fortifications had been repaired. On the military front, he’d demonstrated himself to be the “strategos” of Anatolic (Anatolic Theme).

During the troubled decades before, this “theme” structure kept Byzantium alive in world history. These were military districts under a general (strategos) and home to stratiotes, peasant soldiers who managed their farms in peacetime but could be quickly mobilized in case of conflict.

Leo led a successful revolt against Theodosius III from his district in Asia Minor. He was the sixth rebel leader in the 20 years before. Sulaiman’s plan, no doubt, was to capitalize on the country’s seemingly endless internal problems. Theodosius, however, foresaw the impending threat and had adequate facilities constructed. However, Theodosius cleared the field and withdrew to a monastery after hearing that the citizens and soldiers of the capital had made it obvious that they would prefer to put the defense of the city in Leo’s hands.

Bringing Greek Fire to Byzantium

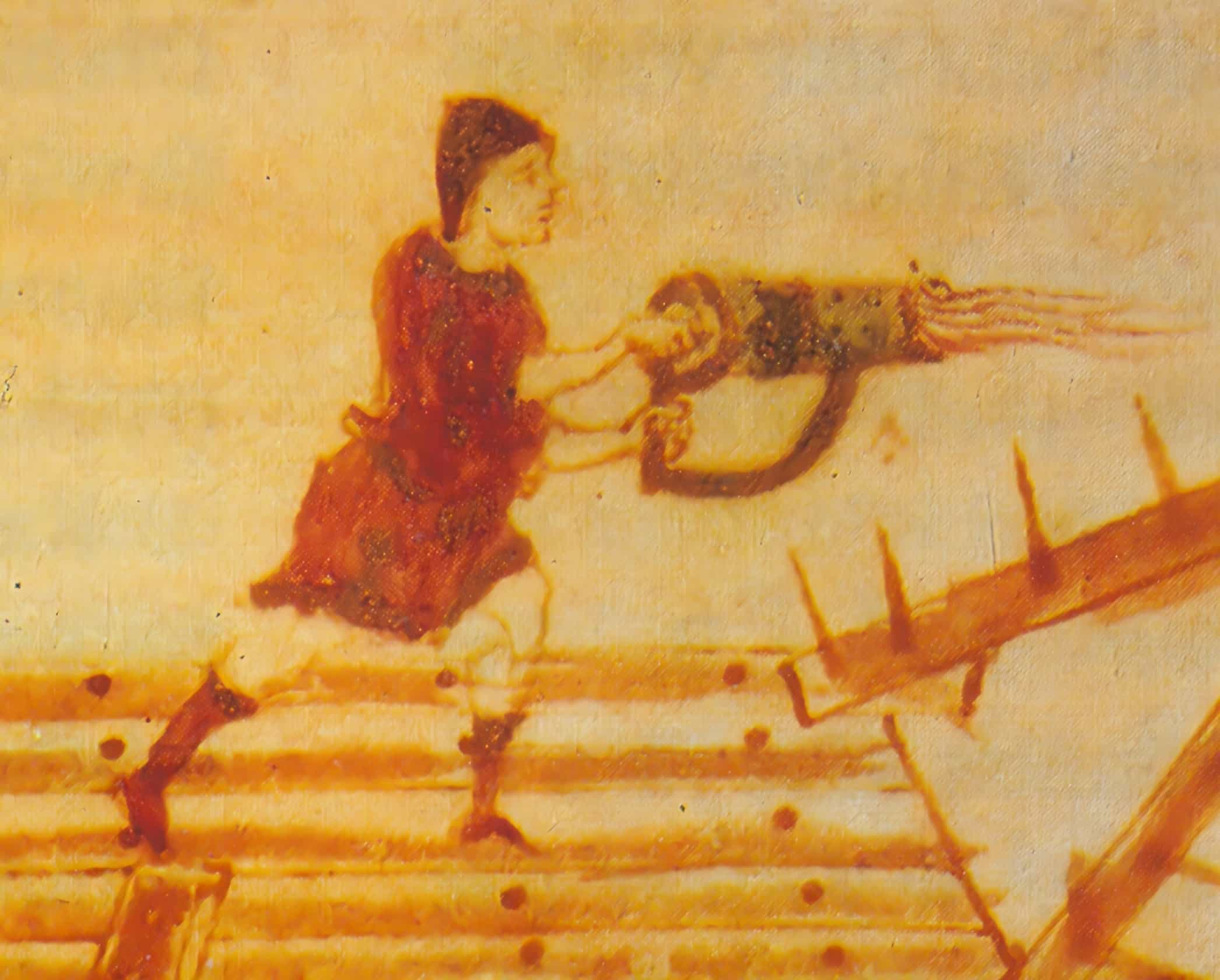

Everything that was hoped for from Leo was realized. On August 15, 717, Meslama, brother of the Caliph, arrived in front of Constantinople with 80,000 men. Compared to the first time an Arab force tried to lay siege to the city in 678, the fortifications and weapons were in much better shape. It was the invention of a Greek architect and alchemist from Heliopolis in Syria, who secretly broke through the siege ring, that ensured Byzantium’s survival: Greek fire.

As a state secret, the exact ingredients of this “pyr thalassion” (sea fire) or “pyr hygron” (liquid fire) remain unknown. The substance was probably a mix of saltpeter and petroleum. It was sprayed onto enemy ships with the help of a pressure pump and bronze siphons or tubes.

This fire blazed at sea and could not be put out with water, making it a terrifying weapon that demanded extreme caution. The dromone was a swift and agile war galley created by the Byzantines for this reason; it was a vast improvement over the Arab ships, which were often timbered from badly kept wood. The noise generated by the burning also acted as a psychological weapon.

Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik started sealing off the land fortifications of Constantinople by surrounding them with a ditch. The caliph and his armada sailed into the Bosphorus on September 1. As the blockade had only been partially successful in 678, he brought with him a large fleet of supply ships to ensure its continuation through the poor season.

Arab Fleet Cannot Escape Greek Fire

Then, out of the blue, a stillness settled in, making it difficult for the small Arab ships to make headway. With “God’s help,” historian Theophanes the Confessor records, Leo immediately had his “fire ships launched,” moored in ports within the sea fortifications and in the Golden Horn, and set fire to the Arab carriers. Part of the ships were lowered to the depths of the sea, while the other was burned on the sea wall.

This made it hard to feed the besiegers through the winter and, in the end, stopped the planned attack on Constantinople’s sea fortifications. A sickness presumably killed Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik as early as the end of September. According to Theophanes, “several horses, camels, and other animals” were lost because Umar, his replacement, chose to keep up the blockade.

The decision was made at sea. The admirals of two Arab fleets decided to shelter their ships from the Greek fire in a harbor in the spring, when the supply issues had been temporarily resolved. Christians on board divulged the information to the Byzantines. Again, “tubes filled with liquid fire on battleships and two oars” were used. “Through the prayer of the Immaculate Mother of God, God helped them, and so the foes were submerged into the water,” Theophanes celebrated.

End of the Arab Dream of Constantinople

Because the Byzantine army cut off the land paths, “a great hunger occurred among the Arabs, so that they ate all the animals that had died, horses, mules, and camels.” There are rumors that they also preserved and ate human bodies and their own waste. When a horrible plague then broke out and the Bulgarians approached with an army from Thrace, “the new caliph” allowed Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik to return.

It was a great triumph for Byzantium. After this, the caliphs stopped launching massive assaults against it and stopped conquering Europe from the east altogether. Fifteen years later, a similar threat in the west was avoided when the Franks, led by Charles Martell, defeated a Muslim force at Battle of Tours (also called the Battle of Poitiers). When the Arab ships were annihilated, Byzantium maintained its dominance in the eastern Mediterranean.

Leo III would eventually be seen as a wise and effective leader who made a lot of good changes. A theological perspective was offered in one of these. To begin the era of iconoclasm and the great iconoclasm in the Eastern Church, he had the great icon of Christ removed from in front of the royal house in about 726. It was to contribute to the alienation between the Western and Eastern churches.

Greek Fire FAQ

What is the formula for Greek Fire?

The ingredients of Greek Fire were likely a combination of petroleum, pitch, sulfur, pine or cedar resin, lime, and bitumen. Gunpowder or u0022melted saltpeter,u0022 according to some theories, may have been included in the mixture.

Did Greek Fire really exist?

Greek Fire was a weapon used by the Byzantine Empire in naval warfare.

Who invented the Greek Fire?

During the reign of Constantine IV Pogonatus (668-685), a Greek-speaking Jewish refugee from Heliopolis named Callinicus invented it.

Sources:

- Leicester, Henry Marshall (1971), The historical background of chemistry, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0486610535

- Moravcsik, Gyula; Jenkins, R.J.H., eds. (1967), Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio, Dumbarton Oaks

- Nicolle, David (1996), Medieval Warfare Source Book: Christian Europe and its Neighbours, Brockhampton Press, ISBN 1860198619

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521791588

- Partington, James Riddick (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801859549

- Pászthory, Emmerich (1986), “Über das ‘Griechische Feuer’. Die Analyse eines spätantiken Waffensystems”, Antike Welt, 17 (2): 27–38