Supposedly, William Ayrton and John Perry, created one of the first automobiles powered by electricity, but it was not rechargeable. Gustave Trouvé created the first actual and practical rechargeable electric car. Inventions and advances abounded throughout the 19th century. The electric motor was one of them. The extensive use of electrically driven vehicles and technologies is not unique to modern times. Its creator, the Frenchman Gustave Pierre Trouvé, who created the first electric automobile, is not as well known as he should be today.

His early life

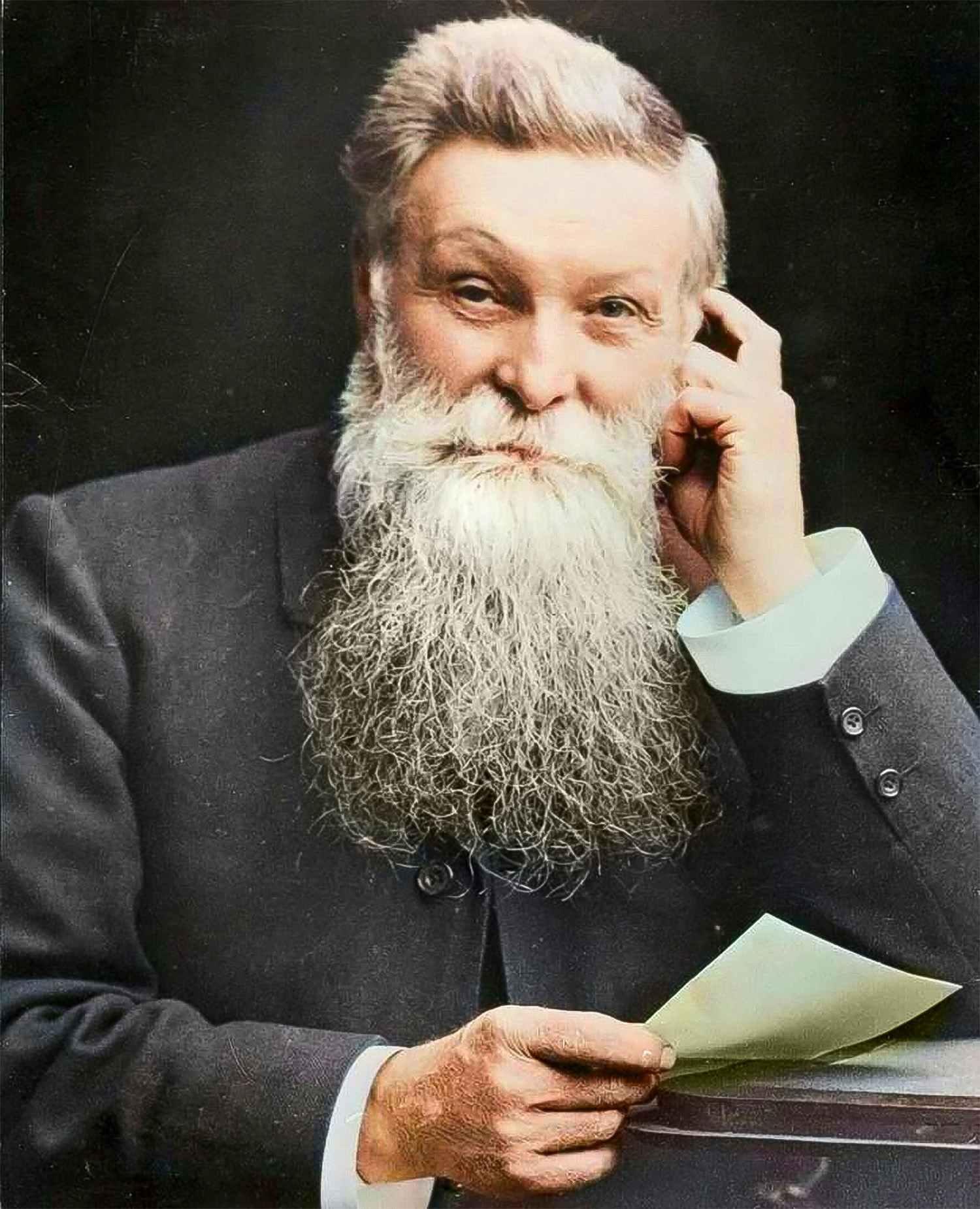

Trouvé, the son of a rich cattle merchant, was born in the little hamlet of La Haye-Descartes in 1839. He had a lackluster academic record, but his aptitude for technology was clear from an early age. Rumor has it that by the time he was seven years old, he had invented a miniature steam engine. Trouvé, then just 20 years old, gained a reputation for himself in the jewelry industry in 1859 after relocating to Paris. His creations, like brooches and figures with beating wings or little bunnies spinning a drum, were driven by a battery he created. This was because the battery, which he developed in 1865, was created specifically to not leak. That made it a great mode of transportation.

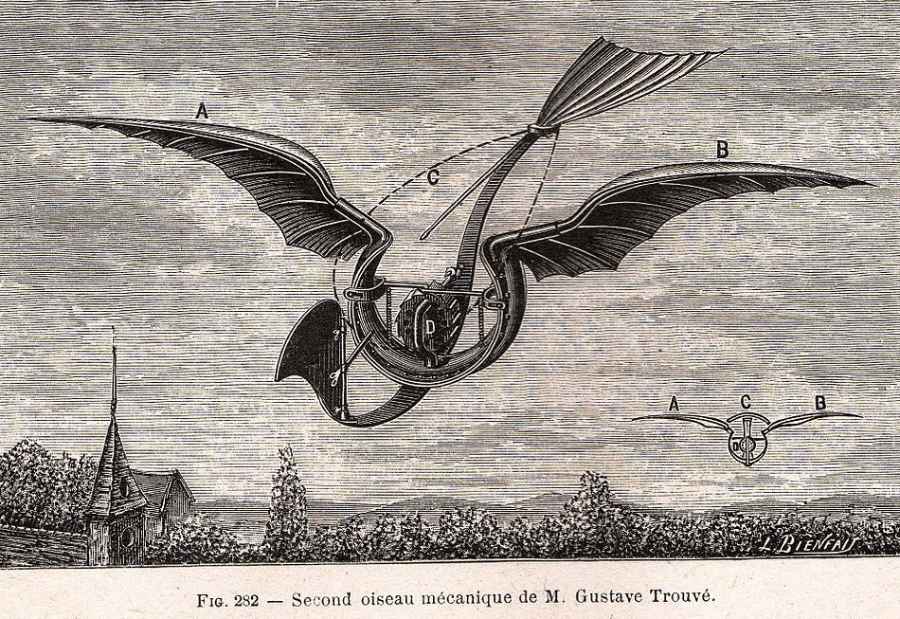

The writer Jules Verne (1828–1905) and the poet Gustave Ponton d’Amécourt (1825–1888) were among the first notable new acquaintances that Trouvé established upon his arrival in Paris. He and d’Amécourt both had an enthusiasm for innovative crafts. The phrase “helicopter,” a combination of the Greek for spiral and wing, is often credited to d’Amécourt, however, Leonardo da Vinci had previously done early research for this field with his “Helix Pteron.”

As soon as Trouvé received his first patent, he and his brother started their own business. The moniker “G. Trouvé” was the one he settled on for his label. Since this sounded like the French phrase “J’ai trouvé,” which means “I have found (it),” it was clear that Trouvé had a mischievous side. That was the French counterpart of Archimedes’ “Eureka.”

Beginning with the metal detectors and ending with the endoscopy

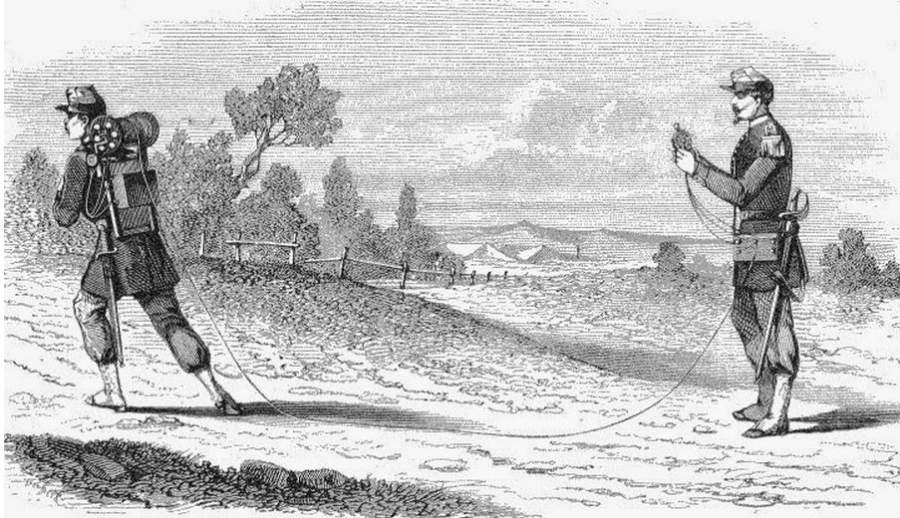

Trouvé made several out-of-the-ordinary innovations over his lifetime. He displayed a battery-operated rifle at the 1867 World’s Fair in Paris. Simultaneously, he developed a medical device, a small metal detector, that would help surgeons locate and remove foreign objects from the human body. During the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, his device saw significant usage by French military medics.

Besides the fixed telegraph, Trouvé also created a portable version. The French military saw considerable potential in the technology and promptly placed an order with Trouvé for 120 units. However, production was slowed down by defective construction supplies. Trouvé was ultimately only able to provide 25 units. The anticipated benefit of the battle never materialized. Soon after that, in 1871, the French government gave up.

The Polyscope was a groundbreaking innovation by Trouvé. It was a light that ran off of one of his little batteries. It was developed to help in medical diagnosis and may be seen as a forerunner to the modern endoscope. At the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair, he presented it to the Austrian emperor, who instantly presented him with a prize. In addition, Trouvé designed a second light for use in medicine with the help of a physician. He coined the term “Photophore” to describe his new kind of headlamp. For his firm, it was an instant hit.

Trouvé designed the first electric car

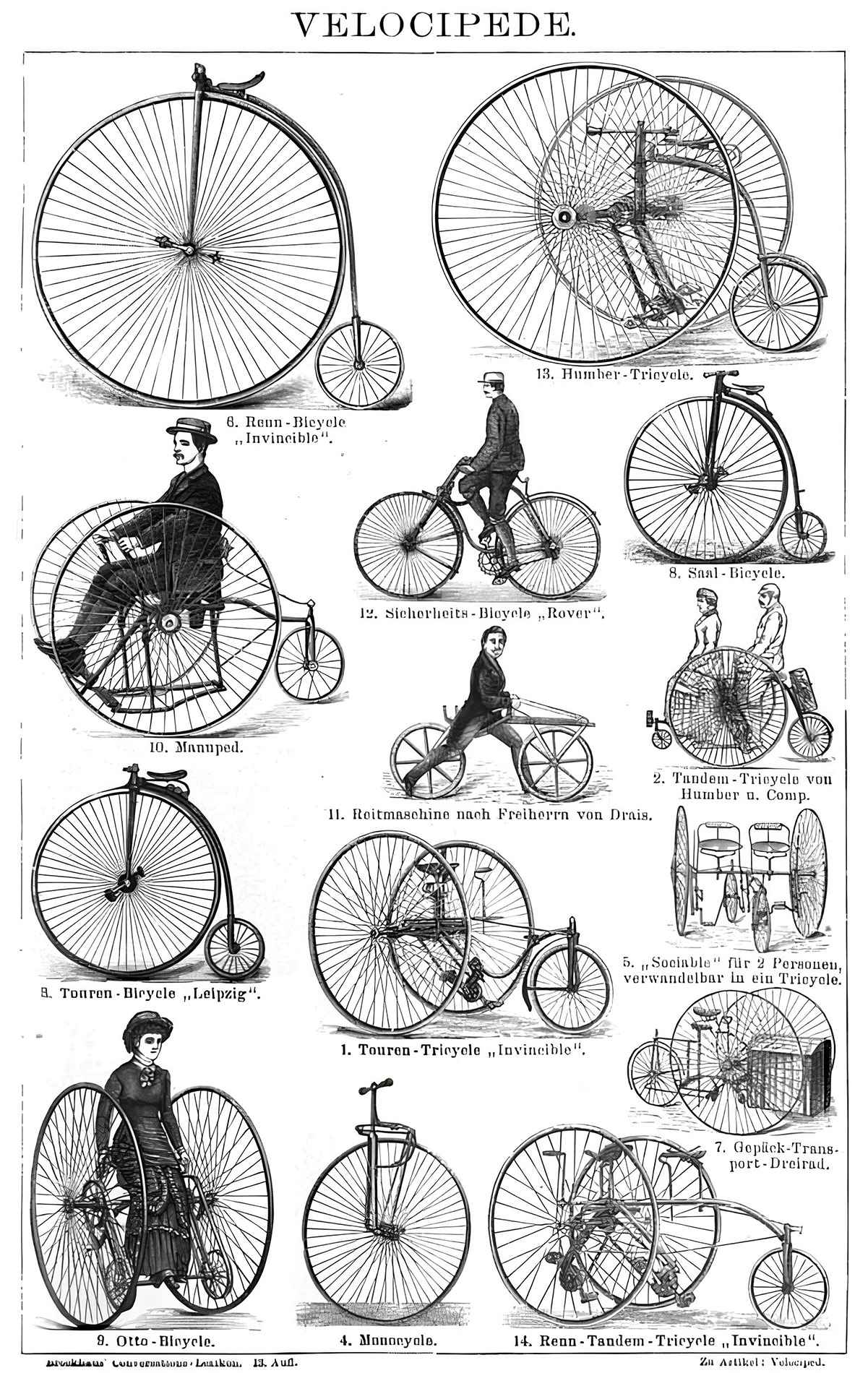

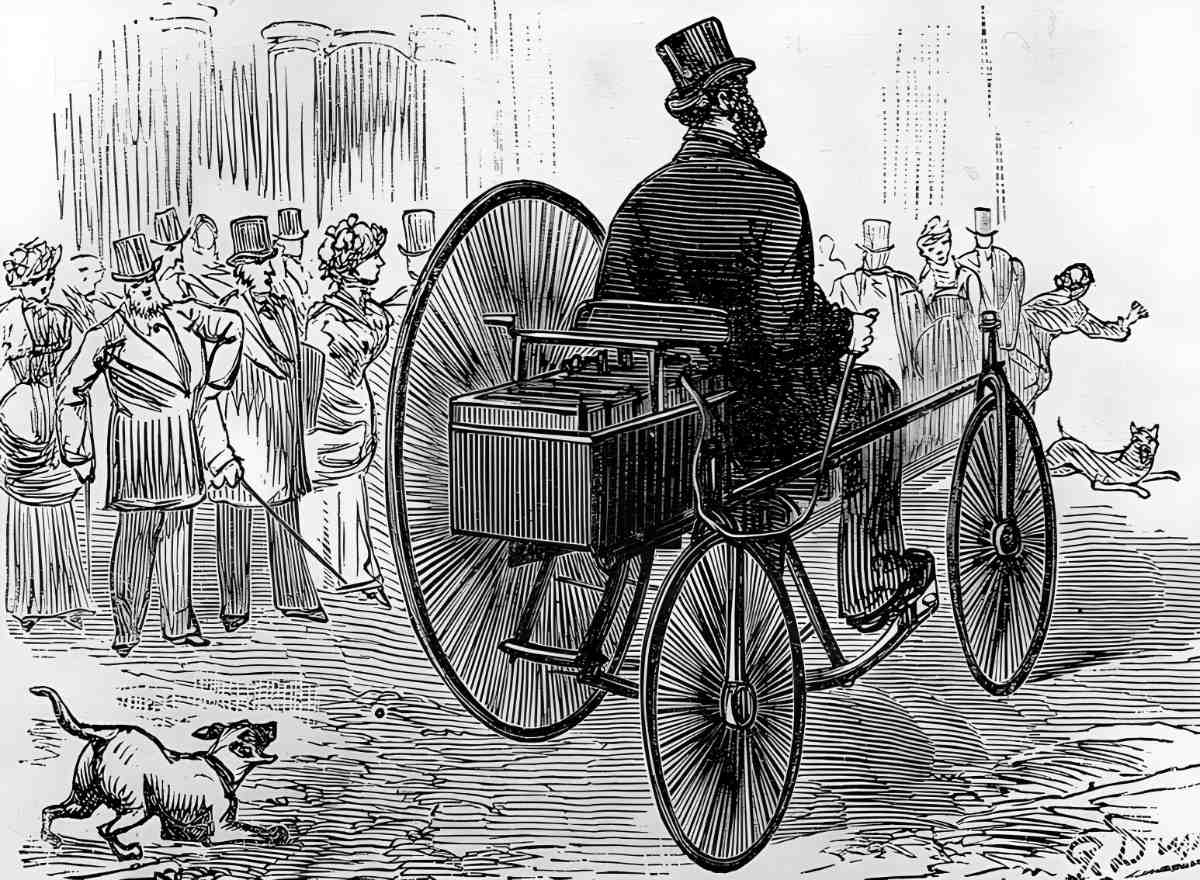

As impressive as it was, it wasn’t even the whole story. From the 1880s forward, Trouvé focused his efforts on the realm of transportation, which was among the city of Paris’ highest priorities at the time. Transportation in the city was mostly provided by horse-drawn carriages, long-distance railroads made use of steam, and the Seine was navigable only by steamboat.

Trouvé took a Siemens electric motor and made it smaller before installing it in a bike he designed out of Englishman James Starley’s tricycle. He utilized a rechargeable battery recently developed by the famous French scientist Raymond Louis Gaston Planté (1834–1899).

The first electric vehicle: It was 1881 when inventor Gustave Trouvé first demonstrated his electric automobile to the public. In Paris, he took his tricycle out for its first voyage.

The first trip out with this vehicle was praised in the Paris media. Even though Trouvé built the first electric car, he never filed a patent for it. And one can only conjecture as to why he did not. Historians think it was related to another patent that a man named Louis-Guillaume Perreaux (1816–1899) had filed a few years previously, this one for a steam-powered bicycle. This patent may have prevented the “Trouvé tricycle” from being licensed.

One of the first outboard electric boats

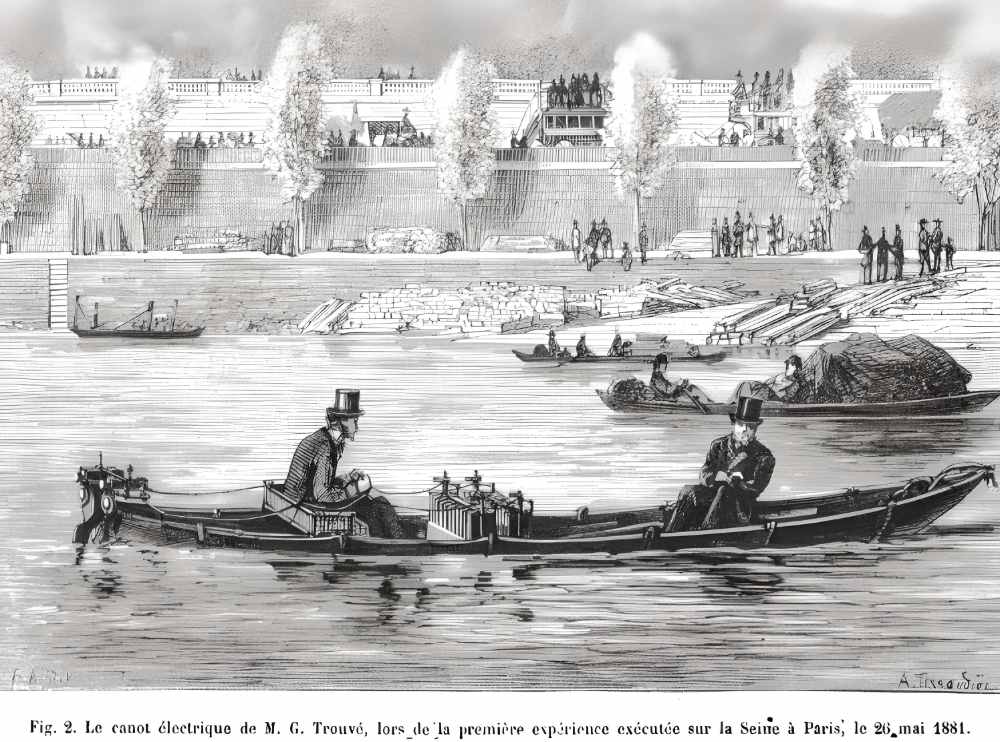

It’s also conceivable that Trouvé just stopped caring. A few months later, he showed off yet another vehicle that ran on electricity. And this time it’s not on the streets of Paris, but rather a boat on the Seine!

The first trip was a success thanks to his own electric engine and batteries he got from Planté. This first electric boat patent was submitted by Trouvé on May 8, 1880. The next decades saw hundreds of boats, from pleasure boats to luxury yachts, fitted with Trouvé’s electric engines, in contrast to the doomed Tricycle. Trouvé also created the first outboard motor by attaching a propeller to his engine.

More than 300 patents were submitted by Trouvé over the course of his life, covering anything from electrically driven missiles to further electric gun designs to different iterations of his medical diagnostic equipment. In 1883, a play by Jules Verne starring one of his inventions had its world debut in Paris.

The female performer wore what seemed to be a brilliantly lit diamond on her head, but was really a piece of cut glass that Trouvé lighted with a battery. Jules Verne, perhaps out of jealousy, banned any further performances, including the diamond, because of the overwhelming positive response from the press. But, he shouldn’t have done that. Because the play was shut down after just 49 showings without the diamond.

During the construction of the Suez Canal, he created underwater lighting.

By the time of his death in July 1902, at the age of 61, Trouvé had spent the better part of the two preceding decades dabbling with electric toys rather than developing any really revolutionary ideas. This may have contributed to how swiftly he was forgotten. Perhaps the fact that, after a few decades of nonpayment, his patents had expired and his importance had been forgotten also contributed.

The only reason Trouvé is somewhat well-known again is because of the author Kevin Desmond’s painstaking research in the 2010s. One of the most successful innovators of the 19th century is now honored with plaques in both his birthplace and his workshop’s former home in Paris. However, he is unlikely to have as many streets named after him as his US inventor colleague Thomas Edison (1847–1931).