Nazis With its onion-domed steeple and octagonal towers, Hartheim Castle is a remarkable example of Renaissance architecture in Upper Austria, a region located west of Vienna. However, the estate has become a symbol of one of the darkest chapters in the country’s history, when it was transformed by the Nazis into a factory of death.

Since the late 19th century, the castle housed an institution for disabled people, managed by a Catholic organization. With the annexation of Austria by Germany in 1938, the facility fell into the hands of the Nazis, and by March 1940, the residents and caregivers were forced to leave and were relocated to other institutions.

A gas chamber was installed in the castle, making it one of the six “euthanasia” facilities of the Aktion T4 program, established in 1939: “It was a centrally organized assassination program, primarily targeting individuals with mental illnesses and disabilities. There was a standardized procedure in all six facilities: the gas chambers were disguised as shower rooms, and carbon monoxide was used to kill,” explains Florian Schwanninger, a historian at the Hartheim Memorial.

The killings began at the castle in May 1940.

The victims were transported by bus from the care facilities where they resided and were executed immediately upon arrival. Their bodies were then burned in a crematorium. Between 1940 and 1941, 18,000 people suffering from mental illnesses or disabilities were gassed under the supervision of two doctors. This tragedy illustrates the findings of a study published last week in the British scientific journal The Lancet. It highlights the “central role” played by the medical profession in the crimes of the Nazis, noting that by 1945, 50 to 65% of non-Jewish German doctors had joined the Nazi Party—a proportion “significantly higher than in any other academic profession.”

Although the Aktion T4 program officially ended in 1941 following protests from parts of the population and the Church, the killings did not stop. Individuals with mental illnesses and disabilities were then murdered in care facilities, often through the use of drugs. From that point on, Hartheim was used to kill other groups, including sick or non-working concentration camp prisoners. Between 1941 and 1944, 12,000 people were gassed there, bringing the total death toll to 30,000.

Among the victims was Klementine Narodoslavsky.

A milliner in the city of Graz, she developed an illness in 1935: “She was diagnosed with what no doctor can explain today: juvenile insanity. We assume it was a form of schizophrenia,” says Raoul Narodoslavsky, her grandson. In January 1941, she was taken to Hartheim and murdered there. She left behind two children, including Raoul’s mother. Today, he strives to keep the memory of his grandmother alive—a woman he never knew and of whom he has only one photograph. He knows the history of Aktion T4 inside out and remains deeply angered by the involvement of the medical profession: “Hundreds of doctors compiled lists of ‘lives unworthy of life,’ and hundreds of nurses watched their patients starve in psychiatric institutions! They made such atrocities possible!

“

Key Dates

- March 12, 1938: Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany

- 1939: Launch of the Aktion T4 program to assassinate individuals with mental illnesses or disabilities

- May 1940: Start of the killings at Hartheim Castle

- July 24, 1940: Establishment of the Am Spiegelgrund clinic

- August 24, 1941: Official end of the Aktion T4 program, though killings continued in different forms

- December 12, 1944: Dismantling of the killing center at Hartheim Castle begins

The murders at Hartheim and under the Aktion T4 program also played a significant role in the implementation of the Holocaust: “Many participants in this program later moved to occupied Poland after its conclusion to develop the extermination camps at Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka. The killings there followed the same pattern as in the Aktion T4 facilities,” explains Florian Schwanninger. Today, along with his team, the historian is working to identify the names of those murdered at Hartheim. Out of 30,000 victims, 23,000 have already been identified.

Medicine in the Service of Child Murder

Today, as one strolls along the quiet, tree-lined paths of the Penzing Clinic in Vienna, it is difficult to imagine the scale of the tragedy that unfolded there eighty years ago. Yet, starting in 1940, a process of murdering children deemed unfit to develop was set in motion at the facility, then called Am Spiegelgrund. This was in line with Nazi doctrine, which advocated for the elimination of “lives unworthy of life” to “purify the Aryan race.” These crimes, carried out by doctors, led to the deaths of nearly 800 children.

Many of the children at this clinic had previously been in orphanages or foster homes. A significant number had mental disabilities, physical deformities, learning difficulties, or neurological disorders.

Upon arrival at the facility, the children underwent medical observation. Caregivers then classified them into different categories, which, in the eyes of the Nazis, reflected their ability to contribute to society and the potential cost they might impose on it. A diagnosis of “unfit for development” was tantamount to a death sentence: From the doctors’ perspective, this meant there was no prospect of improvement in the child’s condition, that they would have to live with their disability, and that they could not be expected to support themselves in the future.

Undernourished, the children lost weight and were at greater risk of developing infections. They were often killed with an overdose of Luminal, a barbiturate that disrupted blood flow to the lungs, making breathing difficult. Many death certificates from Spiegelgrund listed pneumonia as the cause of death.

The bodies were also used for experimentation: “One of the priorities was the study of neurological pathologies. For example, they sought to understand the various causes of what was then called ‘feeble-mindedness’: Was it due to a congenital anomaly or a hereditary disease? Examining the brain and other organs was therefore of great interest to the doctors.

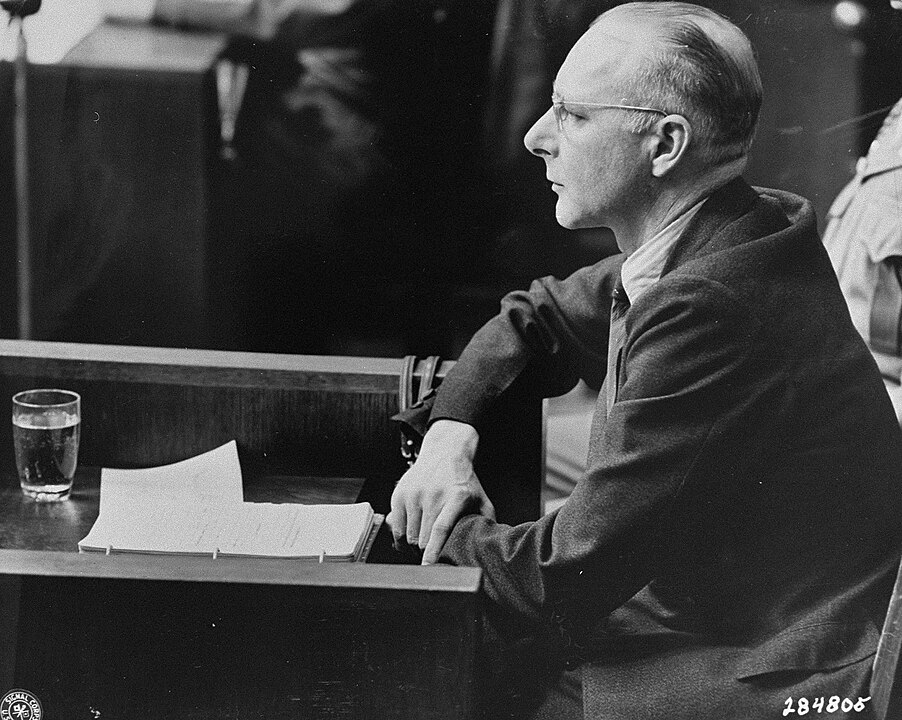

However, the expert refuses to label this as “pseudoscience”: “This term has too often been used to suggest that it wasn’t a problem with science itself but merely the fault of individuals who had gone astray. Many Nazi doctors were fully recognized by the profession and sought to address questions that, at the time, appeared urgent and justified.

” He calls on doctors to learn from this past and, if necessary, to oppose directives that violate ethical principles.