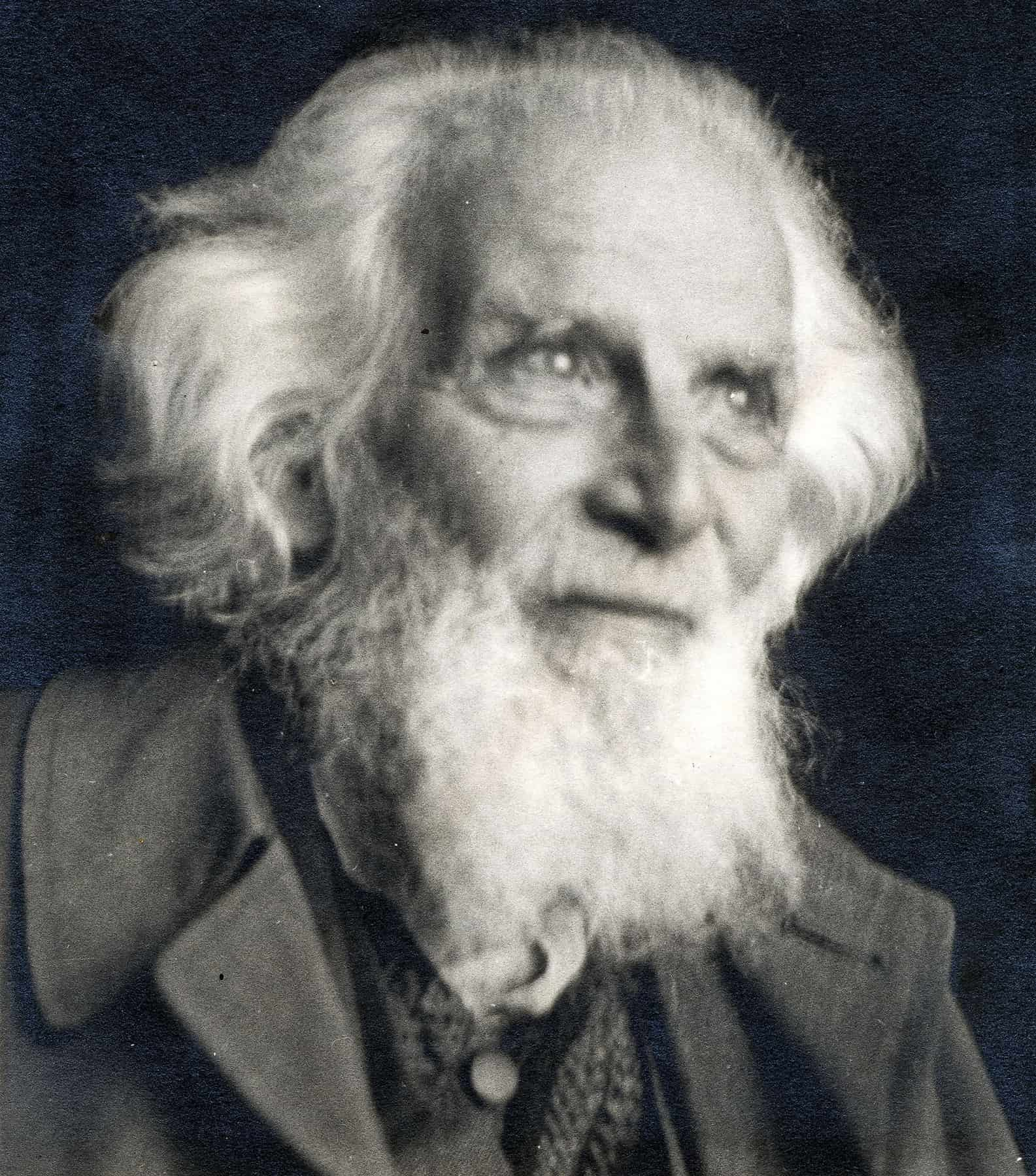

Hatshepsut (Ancient Egypt, around 1513/1507 BC – January 16, 1458 BC) was an Egyptian queen and the fifth ruler of the XVIII dynasty. She was the second woman to definitely hold the title of pharaoh after Sobekneferu of the XII dynasty (around 1806 – 1802 BC). Other women might have ruled, either alone or as regents, over Egypt; for example, Neithhotep, around 3100 BC. She was crowned in 1478 BC and officially ruled alongside Thutmose III, of whom she was both aunt and stepmother, who ascended the throne the previous year at the age of only two. Before that, Hatshepsut had been the “Great Royal Wife,” meaning the principal wife and queen consort, of Thutmose II, the father of Thutmose III. She is generally considered by scholars to be one of the greatest pharaohs in Egyptian history, having also reigned much longer than any other woman from all other native Egyptian dynasties. The American Egyptologist James Henry Breasted described her as “The first great woman in history of whom we have any record.”

Hatshepsut, whose name in Egyptian means “The Foremost of Noble Ladies,” was the only daughter of King Thutmose I (reign: around 1506 – 1493 BC) and the “Great Royal Wife” Ahmose. Her stepbrother Thutmose II was the son of Thutmose I and a secondary wife named Mutnofret, who held the title of “Daughter of the King” and was perhaps the daughter of Pharaoh Ahmose I (reign: 1549 – 1524 BC). Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter named Neferura. Thutmose II had the future Thutmose III (1479 de jure/1458 de facto – 1425 BC) with a secondary wife named Isis.

Early years

Family

The exact date of Hatshepsut’s birth is unknown; it is assumed that she was born in the then-capital of Egypt, Thebes, in the 12th year of the reign of Amenhotep I (1525 – 1504 BC).

It is believed that Amenhotep I had only one son, Prince Amenemhat, who died in childhood (although other sources even deny him this paternity). Therefore, his designated successor was Thutmose I, Hatshepsut’s father, apparently a prominent figure in the army. It is unclear if there was a degree of relationship between Amenhotep and Thutmose; however, it has been hypothesized that Thutmose might have been the son of Prince Ahmose-Sipair, Amenhotep I’s paternal uncle. Amenhotep I may have associated Thutmose with the throne as a coregent before his death, as the cartouche of the former appears alongside that of the latter on a ritual boat found near the third pylon at Karnak. Other texts seem to suggest that Amenhotep I associated his little son Amenemhat with the throne before he died. In either case, archaeological evidence is too incomplete to reach definitive conclusions.

Undoubtedly, Thutmose legitimized his right to rule by marrying a likely sister of Amenhotep I, Ahmose, with whom he fathered Hatshepsut and her sister Nefrubiti. It is unclear if the princes Amenmose, Wadjmose, and Ramose were sons of Ahmose or of a secondary wife named Mutnofret. Of these, only Hatshepsut reached adulthood, as did the other stepbrother Thutmose, her future husband and son of Thutmose I and the secondary wife Mutnofret (unlike Amenmose and Wadjmose, this son of Mutnofret is certain).

Niece, daughter, and wife of pharaohs

Hatshepsut’s father, Thutmose I, managed to expand the Egyptian empire with almost unprecedented skill – in just thirteen years of reign. This great pharaoh is remembered for leading his troops to another very important river of antiquity: the Euphrates. At his premature death, Hatshepsut was in the best position to succeed to the throne, as her brothers had died: it seems that Thutmose I had appointed her as his heir. However, her will regarding succession was not fulfilled, as the throne passed to Thutmose II who, unlike Hatshepsut, was of royal blood only from his father’s side: in fact, the authentic heir, in bloodline, of the founders of the XVIII dynasty was Queen Ahmose, daughter of the heroic liberator of the country, King Ahmose I, and precisely the mother of Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut had to settle for becoming the “Great Royal Wife” of her stepbrother, which perhaps was a blow to her pride.

The young queen was a direct descendant of the great pharaohs who had liberated Egypt from the ancient Hyksos occupiers; she also bore the lofty title of “Divine Wife of Amun,” which marked her as a bearer of the blood of the venerated Queen Ahmose Nefertari, her grandmother or great-grandmother, who was already deified. Thutmose II proved to be a bland and weak ruler, even frail in health, and left no marks of his personality. It is likely that during this period, a circle of supporters as skilled and powerful as Hapuseneb and Senenmut would have gathered around Hatshepsut’s strong personality.

Thutmose III: Hatshepsut’s rise to power

The delicate Thutmose II reigned briefly, perhaps only for three years, before passing away at a young age. When he died, on the third day of the first month of Shemu—that is, in February—of 1479 BC, perhaps not yet thirty, his only two known sons were still very young. As had already happened in the previous generation, the “Great Royal Wife,” Hatshepsut, had not produced an heir to the throne but a daughter; this led to a succession crisis, as described by the official Ineni on the wall of his chapel:

“[Thutmose II] ascended to heaven and joined the gods. The son [Thutmose III] rose in his place as King of the Two Lands. He ruled on the throne of the one who had fathered him. […] The ‘Wife of the God’ Hatshepsut directed the affairs of the country according to her own will. Egypt, with a bowed head, worked for her.”

The young prince Thutmose, son of Thutmose II and a mere concubine or secondary wife named Isis, became the new pharaoh Menkheperre Thutmose, now known as Thutmose III. He must not have been even three years old: due to his age, the widowed queen Hatshepsut assumed the regency of Egypt and indefinitely postponed the marriage between the young pharaoh and her only daughter Neferura, the only one who could fully legitimize Thutmose III’s right to rule. Such a situation was not uncommon: Egyptian history already included several reigning queens, although Hatshepsut was the first to hold such a position without being the king’s mother.

During the early years of Thutmose III’s reign, Hatshepsut prepared a sort of “coup” aimed at revolutionizing traditional Egyptian society. By sidelining the once powerful official Ineni, a supporter of Thutmose II’s reign, Hatshepsut bestowed honors and prestigious positions upon her loyal Hapuseneb and Senenmut. Hapuseneb was probably the most relevant politician in this phase of Hatshepsut’s rise to power, and he held the positions of vizier and High Priest of Amun. With them, the Regent began a propaganda campaign aimed at demonstrating that her father, Thutmose I, had appointed her as his direct descendant and therefore entitled her to ascend the throne. As a culmination of this propaganda effort, Hatshepsut appointed herself coregent alongside Thutmose III, thus assuming all the prerogatives and titles of sovereignty. The duration of the coregency period is uncertain: according to some, the act took place after only two years of regency, while according to others, it dates back to the seventh year of her reign.

Reign

During her reign, Hatshepsut embarked on the task, already begun by her predecessors, of restoring Egyptian contacts and influence over foreign countries, influence that had waned during the “Hyksos period.”

The first expedition, in the 9th year of her reign, to the land of Punt, probably located on the coast of Somalia, is documented by reliefs from the funerary temple of Deir el-Bahari. The expedition, composed of 5 ships “70 feet long,” returned with numerous treasures including myrrh and frankincense trees that were planted in the courtyard of the queen’s funerary temple. In a relief, also from the same location, there remains the grotesque description of the queen of the land of Punt depicted as particularly corpulent. It is presumed, although there is no evidence, that during Hatshepsut’s reign there were military campaigns, or at least actions to maintain the results achieved by Thutmose I’s campaigns in Nubia, Palestine, and Syria. In the 15th year of her reign, the queen celebrated the Sed festival (Heb Sed), which, according to tradition, should have been celebrated only on the occasion of the 30th year of reign.

Before assuming royal power, however, a tomb had already been prepared for Hatshepsut in the Valley of the Kings, discovered in 1916 by Howard Carter and now marked with the designation WA D. On the yellow quartzite sarcophagus, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the inscription reads: “The hereditary princess, great in favors and grace, Lady of all lands, daughter of the king, sister of the king, the Great Royal Wife and Lady of the Two Lands Hatshepsut.” Subsequently, after assuming the throne, the tomb was abandoned and forgotten.

According to popular legend, Hatshepsut is said to be identified with Bithia, the princess who found Moses floating on the Nile, but this legend has been largely discredited by Egyptologists and scholars of the Bible.

Names

Between the 3rd and 7th year of her reign, Hatshepsut assumed all five names of the royal protocol:

| Transliteration | Meaning | Transliteration | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ḥr | Horus | WSR.T K3W | Ka Fill |

| NBTY (Nebti) | The Two Ladies | w3ḏ.t rnp.wt | Thriving of Years |

| ḥr nbw | Golden Horus | nṯr.t ḫˁw | Divine in the Apparition |

| NSW BJTY | He who reigns over the reed and the bee | M3ˁT K3 Rˁ | Maat is the Ka of Ra, i.e. The Truth is the Soul of Ra |

| s3 Rˁ | Son of Ra | ẖnm.t Jmn h3t šps.wt | Loved by Amun-Prima among the Noble Ladies |

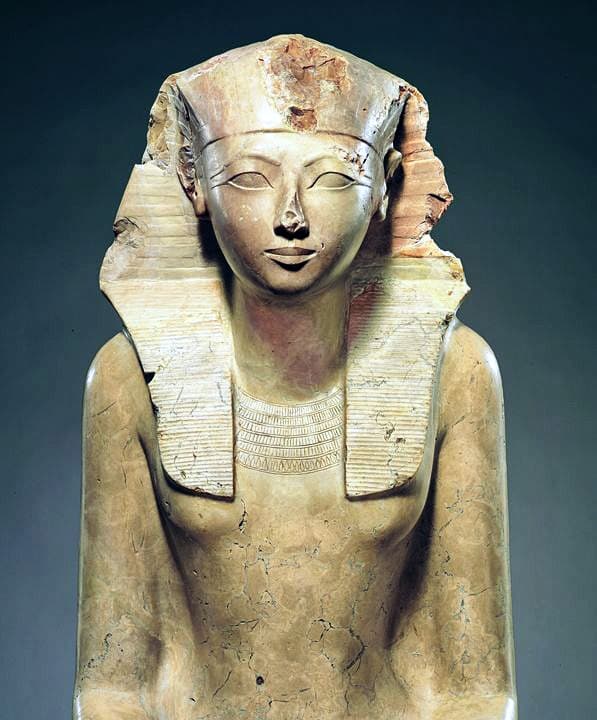

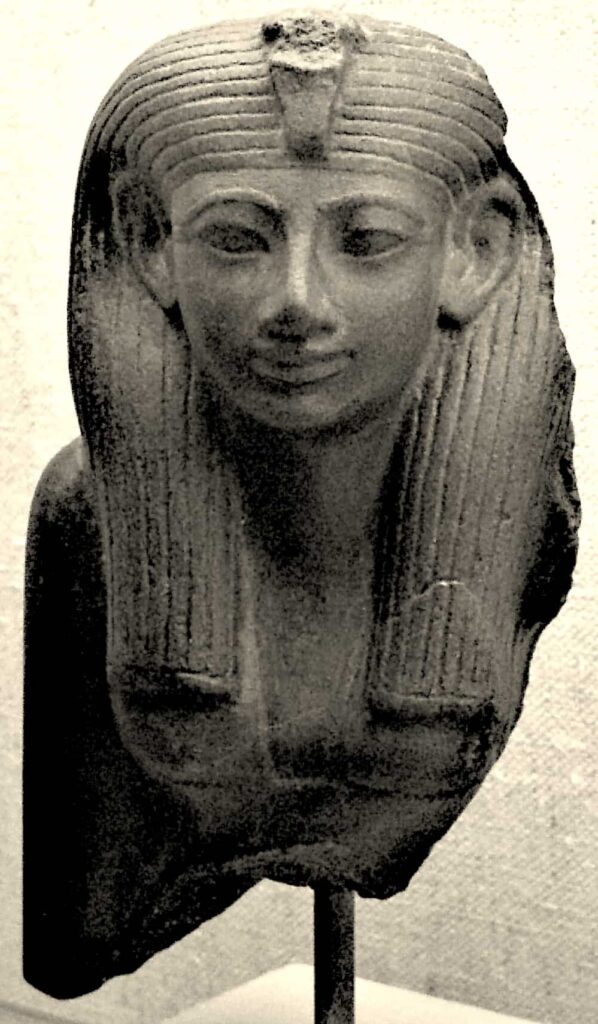

The sovereign, like all pharaohs, was commonly known by the praenomen Maatkara combined with the birth name Hatshepsut. Although the original form of this last name was Hatshepsut, it appears in various forms on numerous monuments: spelled out in its entirety (Henemetamon-Hatshepsut), rendered in the masculine form (Hatshepsu), or spelled as Hashepsu. It is therefore understandable the surprise of archaeologists who discovered the existence of this female pharaoh presented as a male in sculptures and reliefs – but variously male or female in the captions and texts surrounding the images. The sovereign probably exploited these gender changes to enhance her divine character and concentrate in herself the concept of duality, which was extremely important in Egyptian mentality.

Military Activities

Unlike her father Thutmose I and her successor Thutmose III (whom modern historians have nicknamed “the Egyptian Napoleon”), both skilled commanders, Hatshepsut has been portrayed by Egyptologists as a peaceful ruler, more inclined to invest resources in building projects than in the conquest of new territories. However, it is certain that she undertook no fewer than six military campaigns during her twenty-two years of rule. Most of these campaigns seem aimed at deterring neighboring cities, always ready to attack Egypt’s borders.

First Campaign. It was almost customary that upon the death of each pharaoh, the peoples of Nubia would attack the southern borders of Egypt and the outposts’ fortresses, as a provocation to test the reaction of the new monarch. Hatshepsut, who was only a regent immediately after the death of Thutmose II, reacted by going to the frontier and leading the counterattack. An inscription in the Temple of Deir el-Bahari commemorates it:

“A massacre was made among them, the number of the dead being unknown, their hands were cut off […] All the foreign lands then spoke with rage in their hearts […] The enemies were plotting in their valleys […] The horses on the mountains […] their number was not known […] She has destroyed the Land of the South, all lands are under her sandals […] as her father the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Akheperkara [Thutmose I] had done.”

Second Campaign. The enemies, in this case, were Syro-Palestinian tribes, whose continuous aggressions on the borders prompted Egypt to retaliate. The exact date of this second military action during Hatshepsut’s reign is unknown – but it probably occurred after her coronation. Most likely, the sovereign did not leave the capital.

Third and Fourth Campaigns. Again against Nubia. The reason for the Nubians’ frequent hostility towards Hatshepsut is unknown, but Egyptian troops ruthlessly repressed them. The third campaign was in the 12th year of the sovereign’s reign (ca. 1466 BC), the fourth in the 20th year of reign (ca. 1458 BC), and both were resolved without complications. It seems that Thutmose III, then barely in his twenties, participated in the fourth campaign.

Fifth Campaign. Against the country of Mau, in southern Nubia. It took place immediately after the fourth campaign, perhaps due to a coalition of enemies. There is mention of a rhinoceros hunt during this campaign, once again led by the young Thutmose III.

Sixth Campaign. In this case as well, Thutmose III – anticipating his role as a warrior king, which during his autonomous reign would lead to excellent results – marched towards Palestine and captured the city of Gaza, which had recently rebelled. Hatshepsut’s last military campaign took place in the very late part of her reign, just before the queen died. It is easy to notice how the elderly sovereign, by the standards of her time, had taken a back seat, relegated to a merely representative role compared to her energetic nephew, who had assumed the dominant position within their curious family situation.

Building Activities

Hatshepsut is counted among the most prolific builders in Egyptian history, having ordered the creation of hundreds of buildings throughout Upper and Lower Egypt. Her constructions were much more majestic and numerous than those ordered by her predecessors in the Middle Kingdom. Pharaohs succeeding Hatshepsut attempted to claim credit for the erection of buildings actually commissioned by the queen. Hatshepsut appointed the illustrious architect Ineni, who had already worked for her father, her husband, and the royal steward Senenmut, the queen’s chief advisor. During the reign of the sovereign, there was such a rich statuary production that practically every museum of Egyptian antiquities in the world possesses at least one sculpture of Hatshepsut; for example, the “Hatshepsut Room” inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York contains solely artifacts of the queen.

Following the tradition of most pharaohs, Hatshepsut embellished the colossal Temple Complex of Karnak with monuments. She also restored the Precinct of Mut, dedicated to the important goddess wife of Amun, which still showed signs of the devastation caused until a few decades earlier by the foreign Hyksos occupiers; it also suffered severe damage in later epochs after Hatshepsut, when other pharaohs removed building materials to reuse elsewhere, progressively stripping the structure. Hatshepsut also erected two twin obelisks, the tallest of their time, at the entrance of the Karnak Temple, after the fourth pylon; one of the two is still standing and is the tallest obelisk preserved in Egypt (at 29.26 m, it is the second tallest in the world after the “Lateran” obelisk in Rome), while the other broke in two parts and collapsed. Another project, the so-called “Red Chapel” of Karnak, also known as the “Chapelle Rouge,” was built to contain the tabernacle of a sacred boat and was perhaps located between the two aforementioned obelisks. It was covered in carved stone and decorated with scenes depicting significant events in the sovereign’s life.

Later, she ordered the creation of two more obelisks to celebrate the 16th anniversary of her ascension to the throne; one of these obelisks broke while being carved and was replaced by a third. The cracked obelisk was abandoned in its quarry at Aswan, where it still lies. Known as the “Unfinished Obelisk of Aswan,” it has proven useful in understanding the technique used for creating ancient obelisks.

The Temple of Pakhet was built by Hatshepsut at Beni Hasan, near Minya. Pakhet was worshipped as a syncretic form of Bastet and Sekhmet, Egyptian deities who were similar to each other: they were lioness-warrior goddesses, one for Upper Egypt and the other for Lower Egypt; Pakhet was identified with the destructive fury of the summer sun and in the Coffin Texts, she appears as a huntress intent on stalking prey in the depths of the night. This rock-cut temple, excavated into the living rock on the eastern bank of the Nile, was admired over the centuries and nicknamed Speos Artemidos (“Cave of Artemis,” the Greek counterpart of the goddess of hunting) during the Ptolemaic period of Egypt. Many similar temples are believed to have existed throughout Egypt but have been lost. The temple also contained an inscribed lintel with a long dedicatory text, namely a famous diatribe by Hatshepsut against the recent occupation by the Hyksos invaders (translated by Egyptologist James P. Allen). The Asiatic Hyksos had invaded and permanently occupied Egypt, plunging it into a cultural decline that was only reversed by the achievements and reforms of Hatshepsut and her immediate predecessors. The Temple of Pakhet was altered after Hatshepsut’s death, and some decorations were reused by Seti I of the 19th dynasty in an attempt to diminish the traces of Hatshepsut’s existence.

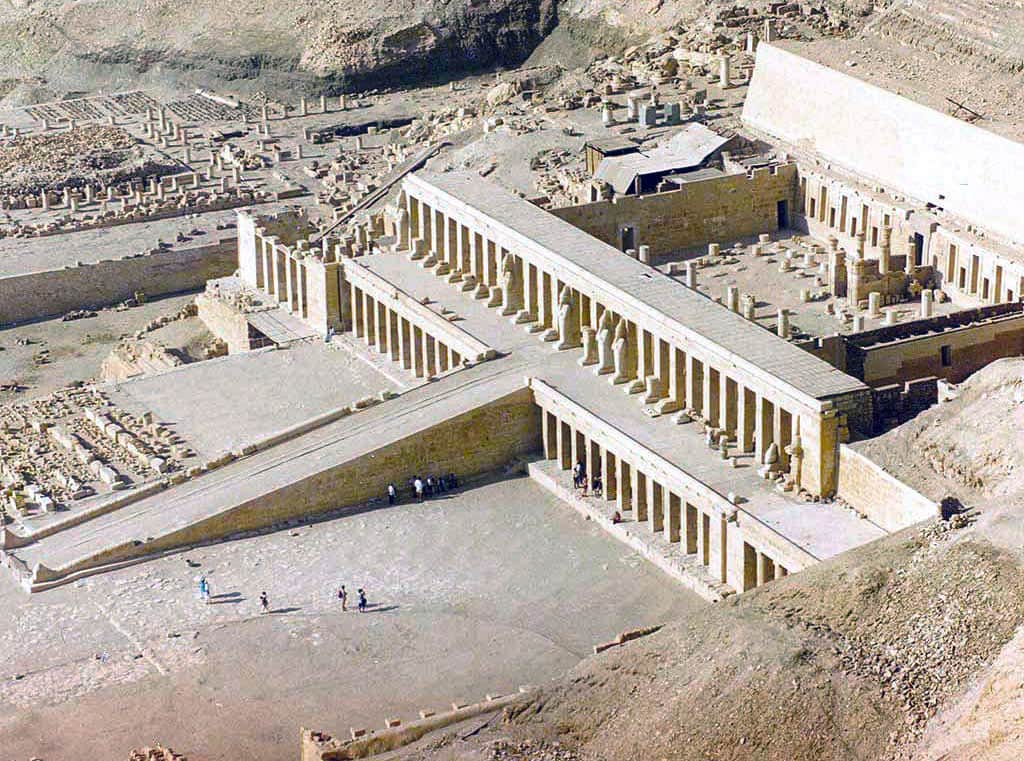

Following a common practice among all her major predecessors, Hatshepsut’s masterpiece was her funerary temple, which she built as a complex at Deir el-Bahari. The architect Senenmut, who served as the queen’s right-hand man and chief advisor, created and improved the design. It is located on the western bank of the Nile, opposite Thebes, and at the entrance of the Valley of the Kings. It was chosen by all subsequent pharaohs of the New Kingdom for their burials, somehow emulating Hatshepsut’s choice. The architecture she desired was the first monument of this scale designed for the area. The focal point of the complex was the Djeser Djeseru, meaning “Sublime of the Sublimes” or “Holy of Holies” or “Wonder of Wonders,” a colonnade whose perfect harmony was anticipated by almost a millennium by the Parthenon of Athens. The Djeser Djeseru is located at the top of a series of terraces that once housed lush gardens, carved into the side of the rocky cliff that delineates the Nile Valley and looms over the entire complex. The Djeser Djeseru and the other buildings that make up the funerary complex are considered a significant advancement in the history of architecture.

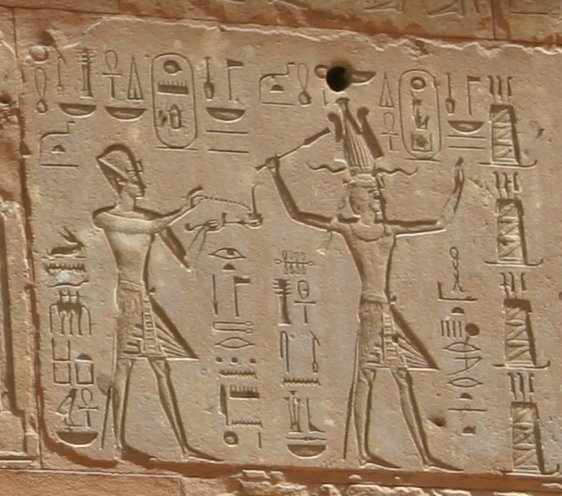

Myth of the Divine Birth of Hatshepsut

One of the most famous moments of Hatshepsut’s propaganda is the myth of her birth, depicted by the queen in an extensive iconographic cycle on the walls of the Temple of Deir el-Bahari, to unquestionably justify her rights to the throne. The composition of the images and texts of this myth would have evoked the consecration with which the god Amun, protector of the dynasty, indicated as the true father of Hatshepsut, had designated her to reign. The narration of the mystical conception and divine birth of the sovereign unfolds like the scenario of a drama divided between earth and sky, with numerous “actors.”

The god Amun expresses his intentions regarding Hatshepsut

At the beginning of the myth, the supreme god Amun appears seated on his throne, consulting with twelve deities about his imminent birth. The scene takes place in the sky. Amun says:

“I desire the companion [Ahmose] whom he [Thutmose I] loves, she who will be the authentic mother of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Maatkara, may she live!, Hatshepsut United with Amun. I am the protection of the limbs until she rises […] I will give her all the plains and all the mountains […] She will guide all the living […] I will cause the rain to fall from the sky during her time, I will ensure that great floods are given in her epoch […] and whoever blasphemes using the name of Her Majesty, I will make him die on the field.”

Amun then tasks the god Thoth to go to earth to observe Queen Ahmose, the future mother of Hatshepsut, and verify her identity. Upon his return, the ibis-headed god of wisdom reports to Amun:

“This young woman of whom you spoke to me, take her now. Her name is Ahmose. She is more beautiful than any other woman in the land. She is the spouse of that sovereign, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Akheperkara [Thutmose I], may he live eternally!”

Union of the god Amun with Queen Ahmose

Then Amun, assuming the form of Pharaoh Thutmose I, accompanied by Thoth, introduces himself at night into the royal palace (however, for greater clarity, the reliefs continue to depict Amun in his usual aspect as a god). The sleeping queen awakens at the god’s arrival. The union between them is not shown but symbolized: Amun and Ahmose sit facing each other on a large bed supported by the goddesses Selkis and Neith, and he gently presses the ankh symbol of life to her face, while the queen delicately touches his other hand. Contrary to the symbolic sobriety of the figures, the text is permeated with fervent sensuality, especially from the moment of Amun’s recognition by the intoxicated queen:

“Then Amun, the excellent god, lord of the Throne of the Two Lands, transformed himself and took on the appearance of His Majesty [Thutmose I], the spouse of the queen. He found her sleeping in the beauty of her palace. The scent of the god woke her up and made her smile at His Majesty. As soon as he approached her, her heart burned, and he made sure that she could see him in his divine form. After he had embraced her closely and she was ecstatic contemplating his virility, the love of Amun penetrated her body. The palace was flooded with the perfume of the god, all the aromas of which came from Punt. The Majesty of this god did everything he desired, Ahmose gave him every possible joy and kissed him. […] ‘How great is your power, it is a pleasant thing to contemplate your body after you have spread throughout all my body [or: when your dew has penetrated all my flesh].’ And the Majesty of the god again did everything he wished of her.”

Finally, disappearing, the god solemnly declares, regarding the newly conceived Hatshepsut:

“She shall exercise a benevolent kingship throughout the land. To her my ba, to her my power, to her my reverence, to her my white crown! Certainly, she shall reign over the Two Lands and guide all the living […] up to heaven. I unite for her the Two Lands in her names, on the seat of Horus of the living, and I will ensure her protection every day, with the god who presides over that day.”

Intervention of the god Khnum and the goddess Heket

The myth continues with Amun commissioning Khnum, the pottery god believed to shape humanity on his potter’s wheel, to mold and give form to the body and soul (ka) of Hatshepsut:

“Go! To shape her, she and her ka, starting from the limbs that are mine. Go! To shape her better than any god. Form for me this daughter of mine that I have procreated […]

[Khnum replies] I will give shape to your daughter […] Her forms will be more exalting than those of the gods, in her splendor as king of Upper and Lower Egypt.”

Heket, the frog-goddess of childbirth, appears kneeling in front of the wheel on which the body and soul of Hatshepsut are taking shape, represented as two distinct children, and she approaches the ankh symbol of life to the face, as Amun had already done with Ahmose in the scene of the embrace. This scene symbolizes and synthesizes the slow formation of the fetus during pregnancy. It is interesting to note that both the figures of the body and the soul of Hatshepsut have male genitals: it is not the person of the historical Hatshepsut that is represented, but, as French Egyptologist Christiane Desroches Noblecourt emphasized, “the holder of the royal function and her ka”, that is, the concept itself of “pharaoh.” More closely related to physical reality, however, the grammatical forms in the texts accompanying this iconographic cycle are conjugated in the feminine.

“Annunciation” to Ahmose, divine birth and presentation to Amun

Subsequently, Thoth appears again – ambassador of the gods like the Greek Hermes to whom he was subsequently assimilated – before Queen Ahmose. Standing facing each other, Thoth extends his arm towards the woman (a gesture in Egyptian art denoting the act of addressing someone). Ahmose stands upright, with her arms stretched along her body, immobilized by astonishment and emotion. After the nine-month time jump of pregnancy, Khnum and Heket go to take Queen Ahmose by the hand, to lead her to the delivery room pronouncing blessings. Ahmose’s belly is delicately rounded (a very rare anatomical detail in Egyptian art). Khnum says to the mother in labor:

“I wrap your daughter in my protection. You are great, but she who will open your womb will be greater than all the kings who have ever existed until today.”

Just as the embrace between Amun and Ahmose, the birth of Hatshepsut is also described in purely symbolic terms. The queen appears seated on an archaic throne, with the newborn already in her arms, and the throne is located on the top of two huge lion-headed beds, stacked, while, at the ends of the scene, Amun and the womb-goddess Meskhenet impart blessings. This scene occupies 7 meters of wall and is crowded with divinities, geniuses, spirits, and divine wet nurses: Amun, Meskhenet, Isis, Nephthys, Bes, Taweret, the geniuses of the ancestors and the cardinal points, a goddess whose headdress is a basket in which the umbilical cord and placenta have been placed, and many other deities. The goddess of love and joy, Hathor, welcomes Amun who has come to see his new daughter. Then the god, extremely happy, holds little Hatshepsut to his chest, recognizes her as his own, and confirms her in her royal rights. Toward the conclusion of the entire cycle, twelve squatting geniuses appear, each holding an image of the newborn; adding to these the other two infant images of Hatshepsut, immediately next to them in the arms of two nurses, the total of fourteen real kas believed to form the pharaoh’s complex ka on earth is reached. Finally, the two great geniuses of milk and flooding present Hatshepsut to Amun, who, together with Thoth, purifies her with a jug of sacred water – to then present her as his heir to the southern and northern deities.

Death, mummification, and burial

Time and cause of death

Hatshepsut died at a mature age, around her 22nd year of reign. The precise date of Hatshepsut’s death – and the date when Thutmose III finally became pharaoh of Egypt – is believed to be the “22nd year of reign, 2nd month of Peret, 10th day,” as attested by a stele found in Armant: January 16, 1458 BC. No contemporary source mentions the cause of her death. If the recent identification of her mummy were correct, medical analysis would indicate that Hatshepsut would have suffered from diabetes and bone cancer that would have spread throughout the body of the fifty-year-old queen; she would also have been affected by arthritis and poor dentition.

Translocation to various tombs (KV20, KV60)

Hatshepsut had begun the construction of her own tomb when she was still the “Great Royal Wife” of Thutmose II: However, the dimensions of this burial did not befit a pharaoh: so, when she ascended the throne, she began to build a new, much more majestic funerary complex. The tomb KV20 of the Valley of the Kings, originally created for her father Thutmose I (perhaps the oldest in the entire Valley), was thus enlarged and provided with a new burial chamber for this purpose. She renewed her father’s tomb and prepared it for a double burial: precisely to accommodate her own mummy and that of her father. Thutmose I was placed in a new sarcophagus originally intended for Hatshepsut. It seems very likely that, at the time of her death, her wish was granted, and she was buried next to Thutmose I in KV20.

However, during the reign of her nephew Thutmose III, it was decided to move Thutmose I to the new tomb KV38, with a new funerary equipment. Consequently, Hatshepsut may have been moved to the tomb (KV60) of her wet nurse Sitra. A possible promoter of these movements could have been Amenhotep II, son of Thutmose III and a secondary wife, in an attempt to consolidate his succession rights. Beyond the objects found by Howard Carter during his exploration of KV20 in 1903, elements from Hatshepsut’s funerary equipment have been found elsewhere: a bed headboard (often mistaken for a throne), a board game called senet, game pieces in red jasper bearing her pharaonic titles, a seal ring, and a fragmentary ushabti statuette bearing her name. In the famous cache of royal mummies at Deir el-Bahari, an ivory canopic chest bearing the name “Hatshepsut” was found, containing a mummified liver (or spleen) and a molar with only part of the root. Among the mummies in the cache at Deir el-Bahari, however, there was one belonging to a noblewoman of the 21st dynasty, namesake of Hatshepsut, and initially it was believed that the chest belonged to the latter.

Identification of the mummy

In 1903, Howard Carter unearthed a tomb (KV60) in the Valley of the Kings where the mummies of two women lay, one identified with Hatshepsut’s wet nurse, Sitra, and the other never recognized (she is a middle-aged woman, obese, with poor dentition and auburn hair, just under 5 feet 3 inches tall). This unknown corpse, with a mummification posture typical of members of the royal family, was removed in the spring of 2007 by Dr. Zahi Hawass of the Supreme Council of Antiquities and taken to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo to be analyzed. The mummy lacked a tooth, perfectly matching the molar found in the canopic chest from Deir el-Bahari (the missing part of the root is still in the mummy’s jaw, which dispelled the last doubts about her recognition). Her death has been attributed to the use of a cancerous ointment, which would have led her to develop the bone tumor that killed her. Helmut Wiedenfeld, of the Pharmaceutical Institute of the University of Bonn, stated:

“Many clues speak in favor of this hypothesis. If one imagines that the queen suffered from a chronic skin disease and found short-term relief in the ointment, she would have exposed herself to great risk over the years.”

(Helmut Wiedenfeld)

On April 3, 2021, her mummy was moved with the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade from the old Egyptian Museum to the new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

Damnatio memoriae and gradual rediscovery

Destruction of monuments

Towards the end of the reign of Thutmose III and during that of his son Amenhotep II, the gradual erasure of Hatshepsut from some monuments and from some pharaonic chronicles began. The elimination of her figure and her cartouches was carried out in the most “literal” way possible, often leaving the context intact: her silhouette or the shapes of the hieroglyphs of her names remained clearly recognizable. Many of her sculptures, on the other hand, were shattered.

At the Temple of Deir el-Bahari, many statues were removed and smashed or disfigured, and then buried in a pit. At Karnak, an attempt was made to hide one of her obelisks with a wall. It is clear that much of this destruction and amendment of historical documents about the controversial sovereign took place already under Thutmose III (reign: 1479 de jure/1458 de facto – 1425 BC), although the triggering cause remains uncertain, beyond the conventional self-promotion at the expense of predecessors typical of numerous pharaohs and their administrators and, perhaps, in an attempt to save resources for the construction of Thutmose III’s tomb, reusing that of Hatshepsut.

Hypothesis of Amenhotep II as the instigator of the damnatio memoriae

Amenhotep II (reign: 1427 – 1401 BC), son of Thutmose III, who reigned as coregent during the last years of his father’s reign, is considered by some to be the true promoter of Hatshepsut’s cancellation in the later period of the old (or sick) Thutmose III’s life. The Italian Egyptologist Franco Cimmino described Amenhotep II’s character as follows:

“He had neither the cultural interests nor the diplomacy nor the great political vision of his father; impetuous, choleric, and disdainful […]”

(Franco Cimmino)

His motive may have been the uncertainty of his own right to rule, as the son of a secondary wife and not of the “Great Royal Wife.” He certainly replaced the sovereign, who had died decades earlier, attributing many of her achievements to himself and replacing her in depictions. Unusually, Amenhotep II did not record the names of his wives, eliminated the titles and prestigious roles of the women of the royal family, and drastically reduced the influence of the “Divine Wife of Amun” office, then held by his sister Meritamon (it seems that, mainly linking himself to women outside the royal family, Amenhotep II tried to interrupt the dynastic line; his only known wife was a woman of uncertain origins, named Tiaa).

Hypothesis of Thutmose III as the instigator of the damnatio memoriae

For many years, assuming that Thutmose III acted without rancor once he became pharaoh (February 1458 BC), early Egyptologists read these censures of the sovereign as something akin to the damnatio memoriae in ancient Rome. This scenario, however, suited the image of a Thutmose III reluctant to share power with his aunt/stepmother for years. However, this is a simplistic interpretation. It seems unlikely that Thutmose III – not only one of the most successful pharaohs in Egyptian history, but also an acclaimed athlete, writer, historian, botanist (Thutmose III Botanical Garden), and architect – would have allowed Hatshepsut to usurp his throne for two decades. Cimmino adds:

“For historians, it is a real puzzle that a charismatic and extraordinary personality like Thutmose III, a great military leader, a shrewd administrator, a very skilled politician, an indefatigable builder, and a courageous innovator, endured for so long such an anomalous situation that deprived him of the legitimate management of the kingdom.”

(Franco Cimmino)

The scraping of Hatshepsut’s images and names was sporadic and proceeded in rather random order: only the most visible and accessible figures were removed (otherwise, if the destruction had been meticulous and complete, we would not have such a rich iconography of the sovereign). Thutmose III died before these changes were completed, but he probably never wanted a total erasure of Hatshespsut’s memory. In fact, there is no evidence that Thutmose III felt hatred or resentment towards his aunt/stepmother: if he had, as supreme commander of the army (a position conferred on him by Hatshepsut herself, who evidently had no doubts about her nephew’s loyalty), he could have easily carried out a strong coup to depose the sovereign and seize the throne of his own father. Canadian Egyptologist Donald Redford noted:

“Here and there, in the deepest recesses of the sanctuaries or the tomb, where no plebeian eye could see, the images and inscriptions of the queen were left intact […] no vulgar eye would ever look at them again, thus maintaining the warmth and fear of a divine presence.”

(Donald Redford)

Hypothesis by Joyce Tyldesley

Scholars like Joyce Tyldesley have contemplated the possibility that Thutmose III may have decided, towards the end of his life and without resentment, to simply relegate Hatshepsut to her institutional role as regent – which was nothing more than the traditional role of the most powerful women in Egyptian history, like Ahhotep I and Ahmose Nefertari – and not that of a pharaoh. Tyldesley argues that by eliminating the most obvious traces of Hatshepsut’s reign as a female pharaoh and reducing her to his mere co-regent, Thutmose III could have easily claimed succession from Thutmose II without any interference from his aunt/stepmother.

The deliberate scraping and hammering of numerous monuments celebrating Hatshepsut’s achievements (but not those hidden from popular view) were probably aimed at obscuring the accomplishments of the sovereign rather than completely erasing them from history. Furthermore, in the latter part of Thutmose III’s reign, the highest officials from Hatshepsut’s time would have died, thus nullifying strong religious and bureaucratic resistance to any attempt to erase their lady’s memory. The most prominent man in Hatshepsut’s reign, her right-hand man Senenmut, suddenly disappears from the sources (likely dying) between the 16th and 20th year of the sovereign’s reign, without ever being buried in any of the two tombs he meticulously prepared throughout his life. According to Tyldesley’s writing, the mystery of Senenmut’s sudden disappearance “has puzzled Egyptologists for decades” due to the sources’ silence on the matter, allowing “the vivid imagination of Senenmut’s scholars to run wild,” resulting in a wide range of solutions “some of which would credit imaginary plots of intrigue or murder.” Amidst such a scenario, the new court officials, owing their fortunes to Thutmose III, would have practical interests in extolling the exploits of their lord, to secure career advancements and benefits.

Assuming that the instigator of the damnatio memoriae was Thutmose III (rather than his heir and co-regent), Tyldesley has also hypothesized that the scraping of Hatshepsut’s effigies would have been a cold and rational attempt to dim the memory of “an unconventional female king whose reign might have been seen by future generations as a serious offense to Maat, and whose not entirely orthodox regency” could have “cast serious doubts on the legitimacy of his [Thutmose III’s] right to rule. Hatshepsut’s crime must have been merely that she was a woman.” Tyldesley’s theory suggests that Thutmose III may have feared that the memory of a successful female pharaoh would demonstrate that a woman was capable of ruling Egypt like a traditional male sovereign, which could have persuaded “future generations of potential, strong female pharaohs” to “not settle for their traditional roles as wives, sisters, and eventually mothers of kings” and, therefore, would have pushed them to aspire to the throne. Dr. Tyldesley speculated that Thutmose III may have overlooked the relatively recent historical event, certainly known to Thutmose III, of a woman who had been a pharaoh – Sobekneferu, of the Middle Kingdom – because she had reigned briefly, perhaps four years, and had ruled “in the very last moments of a dynasty that was dissolving, and from the beginning of her reign events had turned against her. She was therefore [a figure] acceptable, to conservative Egyptians, as a patriotic ‘Warrior Queen’ who had failed” in her attempt to lift the fortunes of Egypt and the dynasty.

Textual clues

The hammering of Hatshepsut’s name – regardless of the motivations behind this gesture and its instigator – almost caused the controversial sovereign’s figure to disappear from Egyptian historiography. When nineteenth-century Egyptologists began interpreting the texts on the walls of the Temple of Deir el-Bahari, their translations proved nonsensical, as feminine terms commented on and described depictions of an apparently male pharaoh. Jean-François Champollion, the Frenchman who deciphered the hieroglyphs, was not alone in feeling confused by the obvious discrepancy between the words and the reliefs:

“I was rather surprised to see, here as in other parts of the temple, the famous Moeris [Thutmose III], adorned with all the regalia of royalty, giving way to this Amenenthe [Hatshepsut], whose name we would vainly seek in the royal lists; I was even more astonished to discover, reading the inscriptions, that, whenever they referred to this king with the beard and the usual attire of the pharaohs, names and verbs were in the feminine, as if it were a queen. I noticed the same peculiarity elsewhere…”

(Jean-François Champollion)

Comparisons with other Egyptian queens

Although autonomous or semi-autonomous rule by a woman in Egypt was unusual, Hatshepsut’s situation was not unprecedented. In the role of regent, Hatshepsut had a precedent in Mer(it)neith (ca. 3100 BC) of the First Dynasty, who was buried like a pharaoh and may have ruled independently, while Nimaathap of the Third Dynasty was probably the widow of King Khasekhemui but certainly acted as regent for her son Djoser (reign: 2680 – 2660 BC) and possibly as a sovereign in her own right. Nitocris (ca. 2200 BC?) may have been the last queen of the Sixth Dynasty, but a fairly widespread opinion among Egyptologists tends to exclude her existence, probably a result of a mistake in reading the sources. Her name appears in the Histories of the Greek Herodotus and the Hellenistic priest Manetho, but on no Egyptian monument. Queen Sobekneferu (1797 – 1793 BC or 1806 – 1802 BC), the last of the Twelfth Dynasty, assumed the title of “Lady of Upper and Lower Egypt” three centuries before Hatshepsut.

Ahhotep I, revered as a warrior queen, acted as regent between the reigns of her two sons Kamose and Ahmose I (reign: 1549 – 1525 BC), at the end of the Seventeenth Dynasty and the beginning of the Eighteenth (Hatshepsut’s dynasty). Amenhotep I (reign: 1525 – 1504 BC), another predecessor of Hatshepsut in the Eighteenth Dynasty, probably became pharaoh at a very young age, which is why his mother Ahmose Nefertari (possibly Hatshepsut’s maternal grandmother or great-grandmother) ruled as his regent. Other women whose possible reigns as female pharaohs are under study include the possible female coregent and successor (1334/1332 BC) of Akhenaten, named Neferneferuaten, and Queen Twosret (1191 – 1189 BC), who concluded the Nineteenth Dynasty. Among the later, non-native dynasties of Egypt, the most notable example is Cleopatra VII (51 – 30 BC), considered the last of the pharaohs, although she was never actually the sole ruler of Egypt, having reigned alongside her father (Ptolemy XII Auletes), her brother (Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator), her brother-husband (Ptolemy XIV), and her son (Ptolemy XV Caesar).