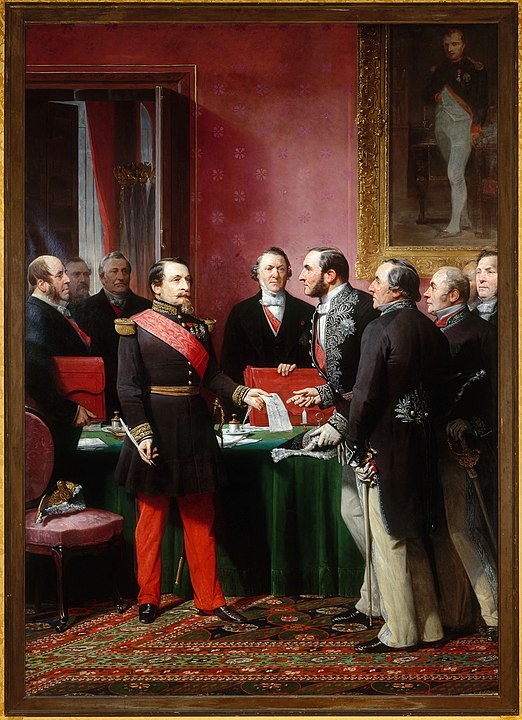

During the second half of the 19th century, during the Second French Empire, Paris underwent extensive renovation aimed at modernizing the capital’s architecture. Initially serving as the President of the Republic, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte worked to address the significant issues afflicting Paris. He observed a lack of hygiene, the absence of proper roads, and, notably, the lack of sewage systems. The evolving traffic in the capital, with the advent of motorization and the first automobiles, also prompted a reconsideration of the city’s road organization.

- What Is Haussmann Architecture? buy cephalexin online https://synemed.com/Media/png/cephalexin.html no prescription pharmacy

- Who Carried Out the Transformations? buy levitra soft online https://synemed.com/Media/png/levitra-soft.html no prescription pharmacy

- Why Was This City Model Chosen?

- How Did the Haussmann-style Construction Work Go?

- What Are the Consequences of Haussmann Architecture?

While Napoleon III outlined the initial plans for the New Paris during his presidency, the implementation of this urban overhaul took shape after his coup d’état and his coronation as emperor in 1852.

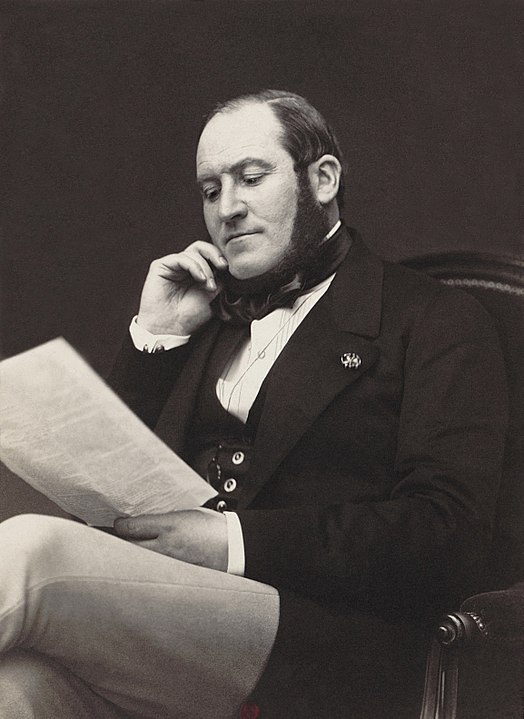

He then enlisted one of his most loyal advisors turned prefect, Baron Haussmann, to organize the construction and develop the plans for Paris, giving rise to what is now known as Haussmann’s Paris. Despite this, the project faced sharp criticism, particularly from liberals led by Adolphe Thiers. The construction efforts spanned nearly 27 years, from 1853 to 1870.

What Is Haussmann Architecture?

buy cephalexin online https://synemed.com/Media/png/cephalexin.html no prescription pharmacy

In Paris, Haussmannian architecture is named after Baron Haussmann, prefect of the Seine during the reign of Emperor Napoleon III. Its aesthetic is highly recognizable: Haussmannian buildings are constructed with cut stone, while the roofing is made of elegant and lightweight blue-gray slate, facilitating easy installation and reducing the load on the framework.

The buildings present distinctive facade lines, contributing to an architectural ensemble and providing more space along the new boulevards, thereby contributing to the modernization of the capital. Parisian urbanism undergoes a transformation!

Who Carried Out the Transformations?

buy levitra soft online https://synemed.com/Media/png/levitra-soft.html no prescription pharmacy

Louis Napoleon Bonaparte is responsible for the transformations in the city of Paris. In the midst of the 19th-century industrial revolution, the emperor aimed to regulate the city, whose architecture varied across districts and arrondissements.

Seeking assistance, he enlisted Baron Haussmann to contribute to this project of standardizing the capital. The initiatives led by Napoleon III were state-directed, involving public entities, while private entrepreneurs managed the implementation.

Why Was This City Model Chosen?

Napoleon III observed that France needed modernization, with the capital serving as the vanguard of 19th-century modernity. Before Haussmann’s interventions, Paris suffered from various disjointed projects initiated first by Henri IV and then by Napoleon I. These efforts focused solely on expanding the capital and its bridges to facilitate transportation across the Seine.

Overall, the city retained architecture inherited from the Middle Ages: narrow streets significantly impeded traffic flow. Additionally, waste and water drainage systems were inadequate, leading to serious hygiene issues. Lastly, the absence of gas lamps and lighting infrastructure increased insecurity when night fell.

How Did the Haussmann-style Construction Work Go?

The state proposed the Haussmannian city model in 1852, thanks to the plans developed by Baron Haussmann. In 1853, he formalized the expropriation of property owners residing in the areas targeted for renovations. Most of the capital’s neighborhoods were gradually demolished, except for the Marais, which retained a significant portion of its infrastructure. The city thus carried out a breakthrough and intersection at Châtelet-Rivoli (1st arrondissement), where commercial areas were concentrated, to facilitate traffic and alleviate congestion. Over forty thousand houses were constructed between 1852 and 1870.

Starting in 1855, the significant north-south and east-west thoroughfare facilitated the movement of populations between the outskirts and the city center. Housing was improved to enhance air quality. Finally, the establishment of sewer systems and an underground water circulation network allowed simplified access to running water while reinforcing the quality of life. Among the major infrastructures, there was the enhancement of the Pantheon, now elevated by the perspective of the Avenue des Gobelins, Boulevard Saint-Germain, Boulevard Sébastopol, Place Louis-Lépine, and the Gare de Lyon constructed for the occasion in 1855, along with the Gare du Nord in 1865.

What Are the Consequences of Haussmann Architecture?

Thanks to Haussmannian architecture, Paris became the symbol of 19th-century aesthetics, characterized by its distinctive facades and balconies, representing modernity. The city served as a preferred backdrop for numerous writers and painters of the time, including Maupassant and Zola, who made modernization a central theme in several of their novels. Monet painted the famous canvas “L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat,” depicting the Gare de Lyon.

Paris inspired other European cities, such as England, with the renovation of London, leading to an improved quality of life. However, critics argued that there was a certain monotony due to the standardization of the districts. Jules Ferry criticized the exorbitant expenses of this project in a pamphlet, while locals perceived these changes as purely for security reasons. The reforms and the availability of small rooms in new buildings attracted poorer populations from the provinces, who were poorly regarded by Parisians at the time.