It was Jawaharlal Nehru, head of the Indian government, who announced the official birth of India on the night of August 15, 1947. His announcement followed that of Ali Jinnah, who had just proclaimed the creation of Pakistan, split into two regions: West Pakistan and East Pakistan. The latter would later become Bangladesh.

The Turning Point of World War II

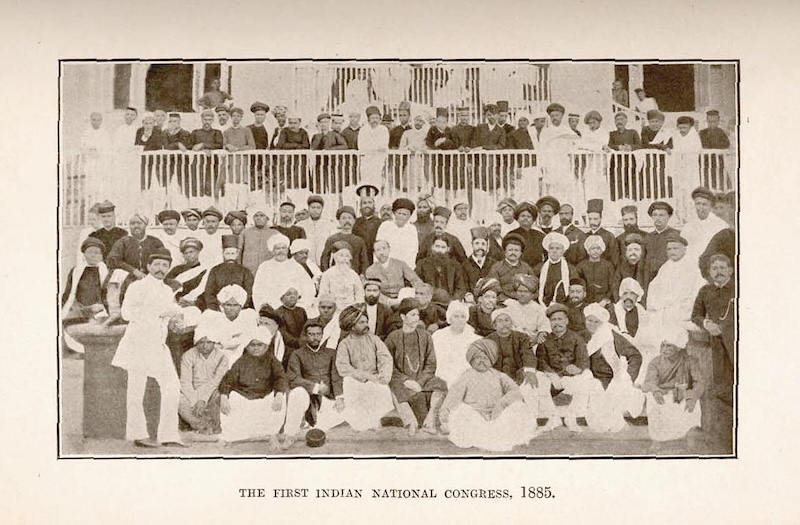

Demands for greater autonomy emerged at the beginning of the 20th century. Initially, these demands reflected a desire for greater Indian participation in the governance of the region. Indians aspired to exercise their own governance and make political decisions without interference from the British Empire. This desire mainly came from the Indian National Congress, founded in 1885 in Bombay, whose more radical wing resorted to terrorism at the dawn of World War I. During the conflict, Indians displayed perfect loyalty to the British.

The interwar period marked the beginning of the first boycott actions and non-cooperation movements. The main figure of this movement was Gandhi. Alongside this non-violent movement, a more radical faction emerged within the Congress, led by Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose. By the late 1920s, the demands had shifted towards a desire for complete independence.

After the tensions of the 1930s, the British granted a much more liberal regime, which only served to exacerbate tensions between Hindus and Muslims. However, it was truly World War II that marked a turning point in the progression of independence demands.

Indeed, the Indian Congress demanded a firm commitment from the British towards independence in exchange for Indian troops’ participation in the conflict. But as the situation in Asia became more complicated with Japan’s entry into the war and the invasion of China, Congress leaders launched the Quit India campaign, aimed at preventing Indian participation in the war.

Antagonism Between Hindus and Muslims

The end of the war coincided with the British government’s desire to resolve the issue of Indian independence. However, tensions between Hindus and Muslims were becoming increasingly acute. The Congress wanted to maintain the territorial unity of what had been the Indian Empire, while the Muslims, led by the Muslim League, sought the creation of an independent Muslim state.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, leader of the Muslim League, forcefully rejected the idea of a confederation between a future Indian state and a future Muslim state. A major issue was the lack of a clear territorial separation between Hindu and Muslim populations.

The creation of two states would thus require massive population displacements.

The Simla Conference on June 25, 1945, marked the first step towards independence. However, during this conference, Lord Wavell, the Viceroy of British India, failed to unite the Hindu and Muslim aspirations. The conference ended in failure on July 14, 1946.

Violent clashes between the two communities followed, and the Muslim League boycotted the Constituent Assembly in December 1946.

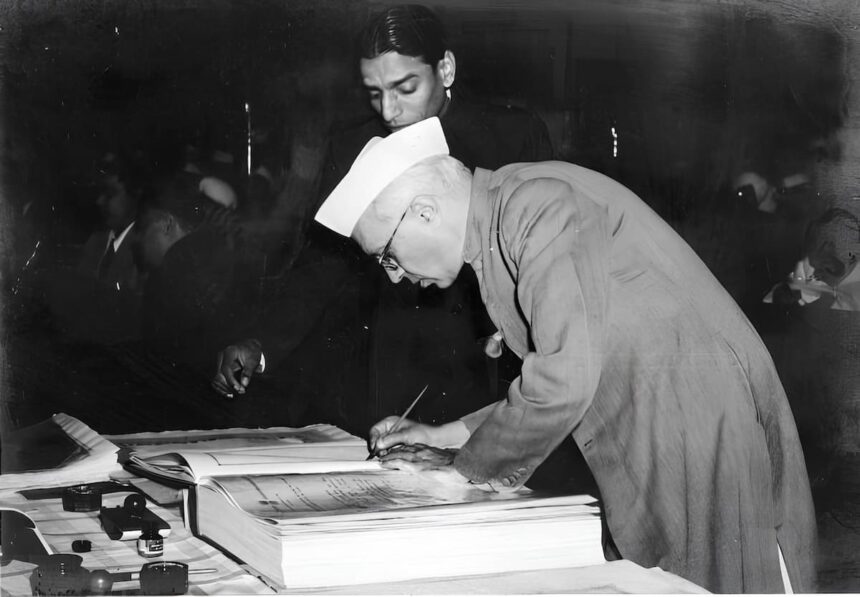

The Declaration of Independence

In this context, the British Labour Party accelerated the process of independence and passed the Indian Independence Act on August 15, 1947. Hindu and Muslim leaders, Nehru and Jinnah, immediately proclaimed the independence of India and the creation of Pakistan. Both states were given dominion status and were integrated into the British Commonwealth (Commonwealth of Nations).

Consequences of India’s Declaration of Independence

This partition had significant consequences. Between 1947 and 1950, over 7 million Muslims fled India for Pakistan, while 10 million Hindus and Sikhs made the opposite journey. These massive population transfers were accompanied by great poverty and extremely precarious conditions. Moreover, the division into two states did not ease tensions, and massacres continued. The summer of 1947 alone saw over 400,000 deaths. Finally, Gandhi, who had worked to avoid these extreme acts of violence, was assassinated by a Hindu fanatic on January 30, 1948.