The infantry in ancient times constituted the most crucial component of armies. The well-known examples include Greek phalanxes and Roman legions, but other military formations were equally vital. Infantry was present in all ancient armies, forming their most essential part for the majority of the time. During antiquity, there was a significant evolution in infantry tactics, accompanied by the emergence of diverse weapons. Most foot soldiers of that era fought with spears, swords, javelins, and bows. Perhaps the most potent weapon was the sword, a symbol of war even today.

Initially, ancient infantry was modestly equipped, armed only with spears and shields. Gradually, infantry started using armor, swords, bows, and various other weapons. As mentioned, the strongest infantry forces belonged to the Roman Empire and Greece. Their armies were nearly invincible, as evidenced by the vast extent of their territories. As infantry declined towards the end of antiquity, it coincided with the decline of the entire Roman army. In 476, the fall of the Roman Empire occurred, marking the end of ancient times, but infantry remained a crucial part of armies into our era.

The First Ever Infantry

Since around 9000 BC, with the advent of settled agricultural communities, warfare began to evolve. Disciplined and hierarchical agricultural societies started forming organized armies. The ownership of permanent territories created the need for large battles where the victorious army could destroy the defeated one, securing additional necessary territories for their leaders. With the advent of civilization, the need for organized, striking units arose.

The phalanx, a formation of infantry fighting in a closed formation with spears or pikes, is one of the oldest military formations. The name “phalanx” itself comes from Greek, meaning a cylinder. Its history is closely tied to the armies of ancient Greece and Alexander the Great, but phalanxes were used two thousand years earlier by the armies of city-states in southern Mesopotamia, which emerged around 3000 BC.

At that time, most weapons were made of low-quality bronze due to a lack of tin in the Middle East. Many weapons archaeologists find from that period are made of silver or gold, often deposited in the tombs of kings or aristocracies. Still, it is assumed that these are enhanced versions of standard field weapons, mainly spears, axes, and daggers. Spears at that time were evidently designed for stabbing at short range, not for throwing, and their tips were securely attached to the shaft to remain in place even after penetrating an enemy’s body or shield.

Axes had rounded edges capable of crushing the helmets and skulls of enemies. Elaborately decorated daggers served as last-resort backup weapons. Considering the importance of fortifications in Sumerian warfare, it’s intriguing that archaeological finds lack throwing weapons, although their use is not entirely unknown. The main component of Sumerian armies probably consisted of phalanxes, standing in the center during battles, while light units with spears and axes fought on the flanks.

Ancient Egyptian Infantry

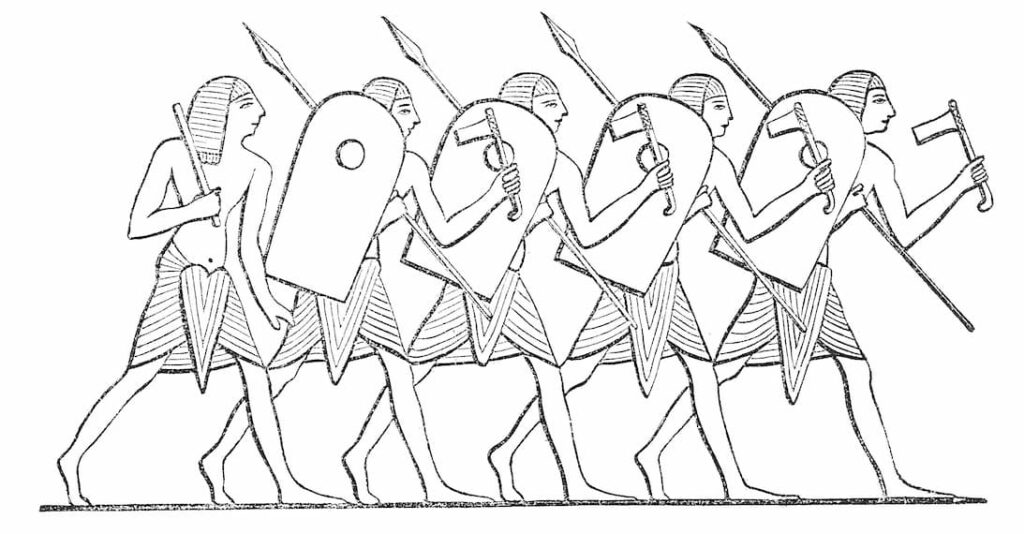

During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (circa 2650–2150 BC), the army consisted of conscripts numbering several tens of thousands, supplemented by mercenary fighters from the Nubian tribes south of Egypt. After the fall of the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom (2050–1640 BC) emerged. The Middle Kingdom’s army was composed of conscripts, where one man from every hundred inhabitants had to serve.

Professional commanders, subordinate to the pharaoh, led the army. Records indicate the existence of commanders of strike units, suggesting the presence of heavy infantry units even at that time. Around 1720 BC, Egypt was invaded by the Hyksos, Semitic people advancing from behind the Sinai, exploiting the country’s political discord and their technological advantage to subjugate Egypt, which they accomplished in 1674 BC. The Hyksos altered Egyptian military culture by introducing technologies from the Near East. They taught the Egyptians to build fast and sturdy chariots for decisive military actions, produce high-quality bronze weapons, and craft composite bows.

The New Kingdom army (1565–1085 BC) combined Egyptian organization, Hyksos techniques, and a new doctrine based on aggressive maneuvers. The core of the army comprised professionals highly motivated by promises of loot, slaves, and land, giving rise to a new warrior caste. During times of war, this army was supplemented by conscripts, each of whom underwent basic training. Egyptian infantry was organized into companies of 250, further divided into squads of 50. There were two main types of infantry: archers, who were fully equipped with composite bows at the Battle of Kadesh, and the Nakhtu-aa (shock troops).

At that time, archers only wore loincloths and were apparently not intended to engage with the enemy directly. However, there was some development in the equipment of Nakhtu-aa soldiers. They were equipped with spears with broad heads, short axes with small bronze heads, and wooden shields with a round upper part. From 1500 BC onwards, armor became common—mostly a reinforced fabric encircling the body, but leather or bronze helmets were also used. Infantry tactics relied on massive salvos of archers, which could decide battles considering the power and accuracy of composite bows (with a range of over 655 feet), the training level of Egyptian archers, and the lack of suitable armor at that time. Archers were evidently deployed in ranks and trained to shoot in salvos, supporting the advance of war chariots or Nakhtu-aa.

The Egyptian infantry also included mercenaries. The Medjay were members of Nubian tribes used as archers in the early New Kingdom. Mercenaries from maritime nations were also employed. During the Battle of Kadesh, Ramesses II had personal guards from the Sherden tribe. The Sherden were the first specialized swordsmen in history, and the metal sword is undoubtedly a weapon of Indo-European nations. Swords were likely initially made of bronze, but iron usage increased around 1200 BC.

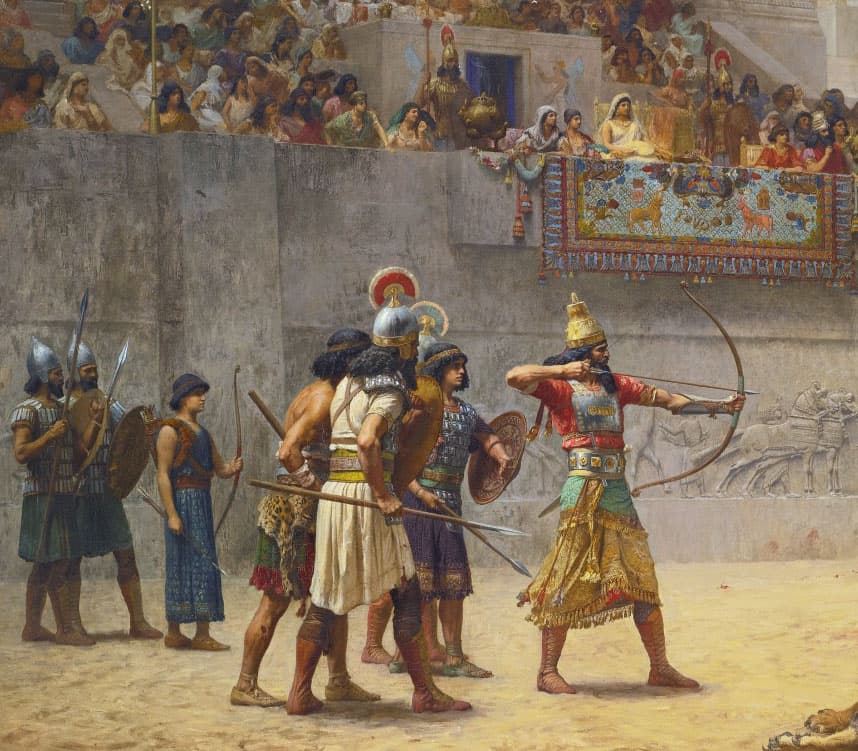

Assyrian Infantry

“I pierced the throats of raging lions, each with a single arrow.”

Ashurbanipal

The Assyrians, alongside the Hittites, were among the first to extensively utilize iron. Unlike tin, which was scarce in the Middle East, iron was abundant, allowing for the production of higher-quality weapons than those made of bronze. Additionally, iron weapons could be mass-produced, enabling the equipping of truly immense armies. In 845 BC, Ashurnasirpal III, the son of Shalmaneser III, marched into Syria with an army of 120,000 men, while the Egyptians had approximately 20,000 men at Megiddo and Kadesh. Shalmaneser III waged war for 31 of the 35 years he spent on the throne. The pinnacle of these conflicts was the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BC, where the Assyrians emerged victorious but suffered heavy losses. At this stage of expansion, the Assyrian army included strike units of war chariots and cavalry, but the backbone was the infantry.

In the Assyrian army, farmers were temporarily conscripted during the summer and released during harvest time to avoid disrupting the agricultural calendar. Archers played a significant role in the Assyrian army. They supported the war chariot attack by shooting from behind shields held by spearmen. Both types of units wore typical Assyrian conical helmets and sleeveless cloaks extending to the ankles—likely made of leather with vertically attached bronze strips. Archers also played a vital role in the siege of cities. Depictions on gates from that era show that each archer had his own shield-bearer, protecting him from enemy projectiles.

After Shalmaneser’s death, weak kings ruled, and the empire declined for eighty years, eventually falling into subjugation to its hated rival, Babylon. Then Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) revived the empire. He implemented extensive reforms in the army. Under his successors, the empire reached its greatest extent. Tiglath-Pileser III replaced farmers with conscripts from each province and also demanded contingents from vassal states. Images from Tiglath-Pileser’s era again depict pairs of archers and shield-bearers, but shields are often replaced by tall, portable reed barriers covered with leather or metal, curved at the top to protect the pair from projectiles at a steep angle. By 700 BC, different formations were also in use. Panels from Nineveh dating between 700 and 692 BC, displayed at the British Museum, depict scenes from Sennacherib’s campaigns.

One panel shows the attack on the Jewish city of Lachish in 701 BC. In the foreground stands a phalanx-like formation of shock troops, deep in six to seven rows, armed with circular shields and 6.5-foot-long spears raised above their heads. The soldiers also wear shortened cloaks and new helmets with a horsehair crest—possibly the helmets of the Kisir Sharruti (Royal Guard). Behind them are six to seven rows of archers, some without armor and others with long cloaks similar to those worn by their ancestors. Three rows of slingers in armor follow. The firepower of archer units was truly formidable (the Assyrian composite bow could shoot up to 2100 feet). Regardless of formations, the Assyrian infantry excelled at sieges, field attacks, guerrilla warfare, coordination with other infantry units and various types of weapons.

Persian Infantry

In 550 BC, the Persian ruler Cyrus II overthrew the last Median king, Astyages, and embarked on campaigns to conquer Babylon and Anatolia. Cyrus’s successors added Egypt, northern India, and parts of southeastern Europe to the Persian Empire. The Persian army at that time relied on conscripts from the provinces and was immense even by standards prevailing 2000 years later. Units were organized into bazarabam (thousands), divided into sataba (hundreds), and then dathabam (tens). The backbone of early Persian armies was infantry, relying heavily on the massive deployment of archers, protected by shield-bearers accompanying them.

The forefront of infantry formations consisted of sparabara (shield-bearers), where sparabara carried rectangular shields made of reeds covered with leather, reaching from ankles to shoulder height. Each dathabam was deployed in a row of ten men, with shield-bearers standing in front of archers. The leader of the shield-bearers wielded a 6.5-foot-long spear for the defense of the entire section. In case their leader fell, archers had to defend themselves with short, curved, spikeless swords as best as they could. Initially, Persians used simple bows with an effective range of around 500 feet, not yet employing composite bows. Persian archers effectively supported attacking cavalry, but their shots lacked the power to deter determined shock units, as seen in the battles of Marathon and Plataea.

In hand-to-hand combat against Greeks and Macedonians, Persians faced a disadvantage due to inadequate armor. Consequently, whenever possible, Persians sought to shoot from prepared positions or behind natural obstacles. Besides Persians and Medes, the main part of Persian armies consisted of contingents from subjugated lands. These soldiers utilized their own national weapons, organization, and tactics.

Over the next 150 years, the Persian army evolved, partially influenced by experiences gained in battles against the Greeks. Between 490 and 479 BC, attempts were made to address the lack of heavy infantry by equipping Kurdish, Mysian, and other mercenaries with shields and spears. Persians also frequently hired Greek mercenaries, especially hoplites. Another unit, the Kardaka, comprised young Persian nobles and, according to Ptolemy, served as heavy infantry.

-> See Also: Panoply: The Equipment of the Greek Hoplites

Greek Infantry

In comparison to the armies of the Middle East, the ancient Greek armies appeared small, technically less advanced, and tactically straightforward. However, the Greeks achieved decisive victories over the Persians at Marathon and Plataea. In 480 BC, a mere 7,000 Spartans and their allies halted at Thermopylae a Persian force at least ten times their size. Greek military culture differed significantly from that of the Near East: Warrior ethics remained strong, and armies relied on aggressive attacks by shock units fighting in phalanxes. Heavy infantry, drawn from private units of wealthy citizens, had a personal stake in the battle’s success and were deeply infused with nationalistic ideology and heroic myths.

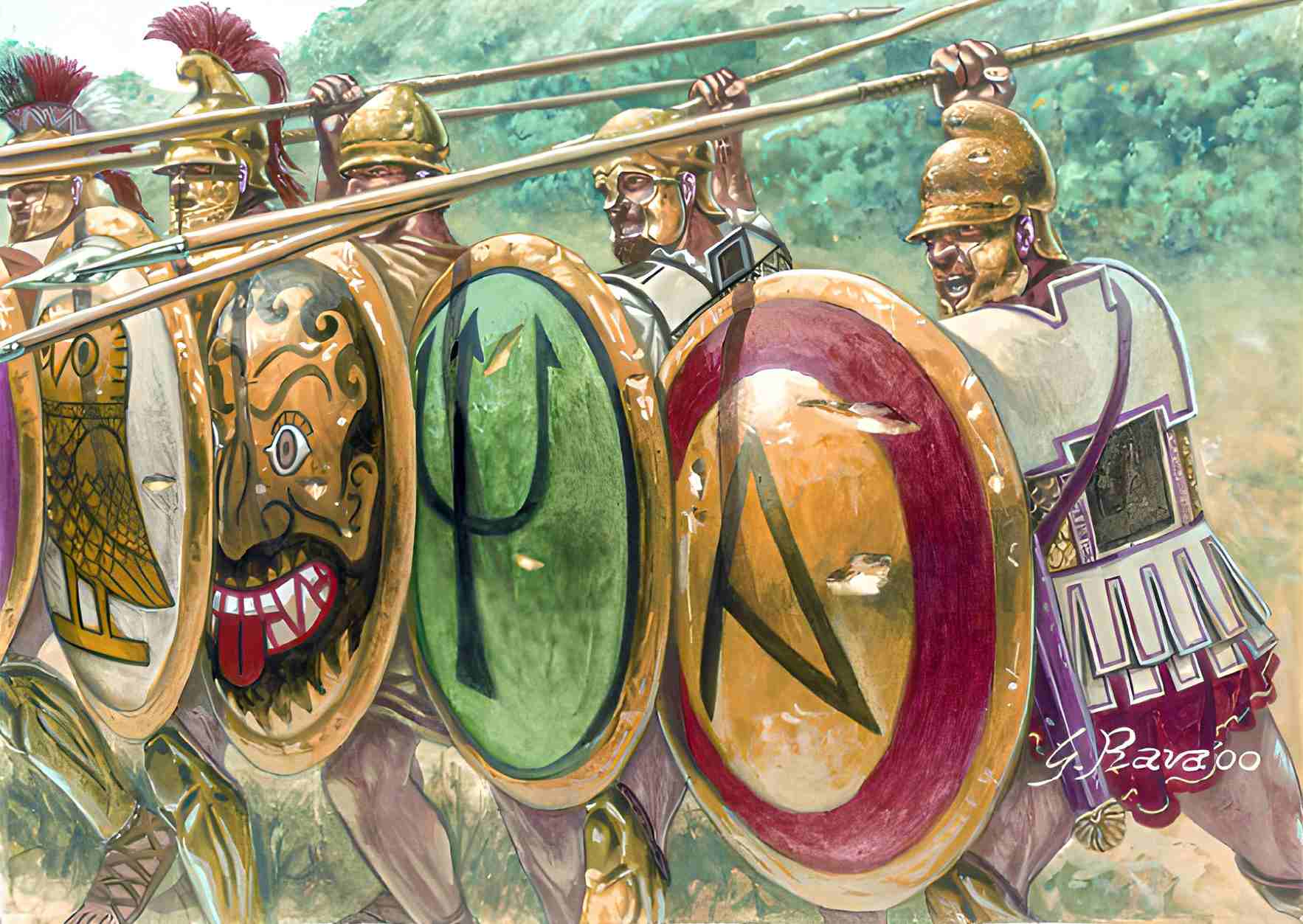

During the Greek Dark Ages, battles resembled uncontrolled brawls. Radical changes began around 700 BC when the phalanx of heavy infantry developed in Corinth, Sparta, and Argos. The political and cultural roots of the phalanx can be traced to the emergence of the polis, dated to around this time. The primary requirement for the polis was the ability to defend itself in times of war. Sparta represented an extreme case, where all men were lifelong soldiers and were not allowed to pursue any occupation other than the military. Even in democratic Athens, all men between 17 and 59 years old had to serve in case of war. Thus, the phalanx was a group of fellow citizens who stood in resistance to an attacker, and their motivation could hardly surpass the motivations of regular conscripts, professional soldiers, or mercenaries.

Basic Equipment

The most crucial part of a heavy infantryman’s equipment was the hoplon, or shield, which gave these units their name (hoplites). The hoplon was essentially a shallow dish made of wood, initially only rimmed with bronze, later fully covered in bronze, measuring on average 30–40 inches in diameter. It had a double handle consisting of a leather or metal strap across the center, through which the arm could be passed up to the elbow, and loops made of leather or rope at the edge, held by the hand.

-> See also: Aspis: The Iconic Shield of the Ancient Greeks

It could be held at the elbow, with part of the weight resting on the shoulder, making it easier to carry but less flexible than a shield with a single handle. The hoplon was adorned with a symbol—faces of monsters, minotaurs, and other creatures were particularly popular. Still, the Spartans enforced strict uniformity, decorating all their shields with the letter lambda, representing Lakedaimonioi, the ancient name for Spartans.

Another significant component of heavy infantry equipment was the helmet, and there were several variants. The most common type was the Corinthian helmet, covering the entire head and face, with a T-shaped cutout for the eyes and mouth; later versions also had a nose guard. Hoplites also used body armor. From the 6th century BC, laminated protectors made of many layers of fabric, with a total thickness of up to 2 inches, came into use. These protectors covered the shoulders and torso, and they included a skirt to protect the abdomen and groin, usually divided to allow walking and running. Leg guards, often shaped according to the wearer’s muscles, completed the heavy infantry’s equipment.

The primary weapon of hoplites was the spear, designed for thrusting and approximately 5 to 8 feet long, with an ash shaft, an iron flat head, and a bronze butt spike. Many swords have been found, but from the 5th century BC, two main types became standard: one was about 24 inches long, with a double-edged leaf-shaped blade for cutting. The second, of Etruscan or Macedonian origin, had an edge on one side and a curved hilt. Swords were used purely as backup weapons; the main weapon of shock troops was always the spear.

Common Tactics

The most common tactic of the phalanx was direct advance and contact with the enemy. Thucydides describes the advance of two armies at Mantinea: The opponent advanced wildly and angrily, while the Spartans advanced slowly to the sound of flutes. This custom had nothing to do with religion; the music aimed to maintain a steady pace, preventing their ranks from breaking during the march. Spartans, and later others, marched into battle to the sound of war songs that urged them to emulate their invincible ancestors. According to contemporary testimonies, phalanx battles against phalanxes were a mixture of shield pushing—othismos—and spear thrusting until one side gave way.

Thucydides, in his description of the Battle of Delium (424 BC), recounts fierce fights on the Theban left wing, where soldiers were stuck together with shields until one of them yielded. Gaps were then created in the Theban lines, into which the Athenians sent their light infantry. Another piece of evidence for the importance of pressure is the increasing depth of the phalanx, which reached fifty ranks with the Thebans at Leuctra. Since their commander, Epaminondas, wanted them to please him and take one more step, it is quite possible that his phalanxes were essentially overwhelming the Spartans. So, even if the phalanx did not crush the enemy at first contact, it could defeat them through gradual weakening, with the most crucial factors being the depth of the formation and the combat determination of those involved.

Peltasts and Other Light Infantry

Similar to heavy infantry (hoplites), peltasts also got their name from the shield they used. The pelta was a crescent-shaped wicker shield with a single handle in the center, covered with goat or sheepskin. Although commonly used in the Mycenaean period, the pelta around the 5th century BC became associated with assault units generally referred to as peltasts. However, this name most appropriately applies to mountain tribes from Thrace (currently northeastern Greece and southern Bulgaria), where the pelta shield originated. Thracian tribes fought in wooded mountainous regions, and their tactics relied on sudden attacks, ambushes, and brief skirmishes, making the Thracians the most renowned light infantry of antiquity.

Thracian peltasts served as conscripts in the Persian army that invaded Greece in 480 BC and as mercenaries in the Greek army from the Peloponnesian Wars onwards. During the Peloponnesian Wars, Greek armies began to use not only shock troops (hoplites) but also assault units (peltasts) and ranged units (archers, slingers). The need to cooperate with and defend against these units of the enemy is reflected in the phalanx tactics.

The Significance of Light Infantry

Greek armies started incorporating light infantry into their forces around 490 BC, with Herodotus claiming that the Athenians had 800 archers at Plataea. However, light infantry was not a regular component of any Greek polis. The shortage of light infantry was felt, for example, during the Peloponnesian War by the Athenian commander Demosthenes, who led units of hoplites and a smaller number of archers into the mountains of Aetolia in central Greece. Like the Thracians, the Aetolians inhabited rugged terrain and developed a warfare tactic that perfectly exploited such terrain. Demosthenes’ hoplites were defeated in a manner later called guerrilla warfare:

They descended from all sides of the mountains, hurling their spears and retreating whenever the Athenian army advanced, only to reappear when it momentarily withdrew. The battle proceeded for a while in this manner, alternating between advancing and retreating. In both cases, the Athenians were at a disadvantage. However, they managed to hold their ground until the arrows of the archers ran out. With the ability to turn the situation using the arrows they had, the lightly armed Aetolians fell easily under the rain of Athenian arrows. However, once the commander of the archers fell, his men scattered. The soldiers, exhausted from constant maneuvering, were caught in riverbeds of dried rivers with no escape or died in other parts of the battlefield when they lost their way. — Thucydides, Athenian historian and general.

In the years following the Corinthian War from 395–387 BC, light units became an integral part of Greek armies, inspired by the talented military innovator Iphicrates of Athens. In the initial phases of the war, Iphicrates supported the Corinthian side and, utilizing large mercenary forces, including Thracians, organized several incursions into Arcadia in the central part of the Peloponnese. In 390 BC, the Spartan army was destroyed near Corinth. Peltasts continually attacked the Spartans, and whenever the Spartans tried to catch them, the peltasts quickly fled.

Due to their light equipment, the Spartans were unable to catch them. After the war, the Athenians hired Iphicrates and his peltasts for many clients, including the Persian king Artaxerxes. They fought in the Persian army, suppressing the Egyptian uprising and performed more than adequately. However, there are no records of using this light phalanx in battle. Still, its influence on the Macedonian phalanx cannot be ignored.

Philip II and the Macedonian Phalanx

After Philip II became the Macedonian king in 359 BC, he initiated a series of military reforms that transformed poorly disciplined feudal levies into one of the most impressive armies of the classical era. Philip professionalized the Macedonian army by introducing military training even in times of peace, regular, structured pay, and allocating land to veterans after completing military service.

Units underwent regular training and marches in full equipment to strengthen the physical condition and instinctive discipline of the soldiers. Alongside these fundamental changes, there were several organizational adjustments. One of the most important was the introduction of a new type of phalanx. During the reconstruction of the Macedonian army, Philip was likely inspired by several sources. From 368 to 365 BC, he was held hostage in Thebes and probably learned much about the Greek phalanx there. He also drew inspiration from Iphicrates and his peltasts.

Philip’s most radical innovation, however, concerned the weaponry. The primary weapon of the Macedonian and Hellenistic phalanx was the sarissa, a two-handed spear carried under the arm, similar to what Iphicrates had introduced. The sarissa adopted by Philip aimed to give his hoplites an advantage in longer reach compared to the spears of Greek armies, and it was also used because a two-handed weapon is more difficult to parry.

According to Polybius, a Greek historian from the 2nd century BC, the sarissa was 20–23 feet long, with 13 feet protruding in front of the hoplites preparing for impact. The Macedonian phalanx advanced in double strength, creating a dense barrier of spears, behind which marched massive rows of men. Philip also chose a formation based more on quantity than the individual’s skills because most men in the Macedonian army were farmers who couldn’t match the Greek hoplites in battle. The hoplites of the Macedonian army had less armor, making the Macedonian phalanx much more mobile than the Greek one.

The Macedonian army was formidable and organized, but it also had its weaknesses. For its effectiveness, it was necessary for the men to trust each other because each individual covered his fellow soldier with his shield, and each unit functioned as a unified entity. Therefore, the men forming the phalanx had to maintain closed ranks under all circumstances, which, however, with proper soldier training and discipline, was not a problem in Philip’s army.

Roman Infantry

Roman Republic Infantry

Until the 6th century BC, the inland tribes of Italy were strongly influenced by the Celtic Hallstatt culture from the north more than the Greeks from the south. The influence of Celtic culture is evident in Roman military history. Combat means were closely related to the tribal model, and there is evidence of the existence of an elite order of victors and war priests dedicated to the god of war, Mars, the father of Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome. The Romans initially fought only with swords; blades up to 28 inches long were found alongside bronze arrowheads. They had helmet types like the calotte, initially shaped like a pot, made of bronze, and worn as hats. Armor primarily protected the chest.

Around 600 BC, the Romans subdued the Etruscans, a people of unknown origin whose culture was centered in several large cities in northern Italy. Shortly before achieving dominance, they incorporated the phalanx of hoplites into their arsenal and introduced its organization to Rome and other subjugated nations. In the Etruscan-Roman army, all adult male citizens of the state served. The population was divided into voting classes known as centuries, with each class equipping itself at its own expense for war according to its financial capabilities. The Romans expelled the Etruscans at the end of the 6th century BC, but they apparently retained the phalanx of the Greek type.

However, in many battles with the Gauls and Samnites, its weaknesses were exposed. The Samnites lived in harsh and mountainous terrain, so most of them were armed with spears, shields, and light armor. The Romans learned from these battles and introduced legions. Legions were divided into maniples, each consisting of two centuries. In the legions, there were hastati, principes, and triarii. Hastati were young men armed with spears (later swords), shields, and light armor. Principes were well-armed men in their prime. The Triarii were old veterans armed with spears and strong armor.

Further Reforms

The Roman legions underwent additional reforms after facing the fast and agile Carthaginian armies during the Punic Wars. As for the army, it still consisted of a militia composed of citizens of the middle and upper classes. Each man was expected to perform military service for sixteen years, up to the age of 46, to which he annually reported during times of war. However, the nature of Roman military power gradually changed: from 392 BC, soldiers received regular pay, making this army more like a modern professional army than a conscripted force.

The obligation to perform military service during the long wars in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC led many legionaries to practically become professional soldiers. Legionaries were granted increasingly more exemptions from property contributions, and after the catastrophic defeat at Cannae, farmers and even slaves were enlisted in the army. A legion consisted of 4,200 men, and this number could be expanded to 5,000. The legion was divided into centuries of 80–100 men, and two centuries formed one maniple, the main tactical unit of the Roman army at that time.

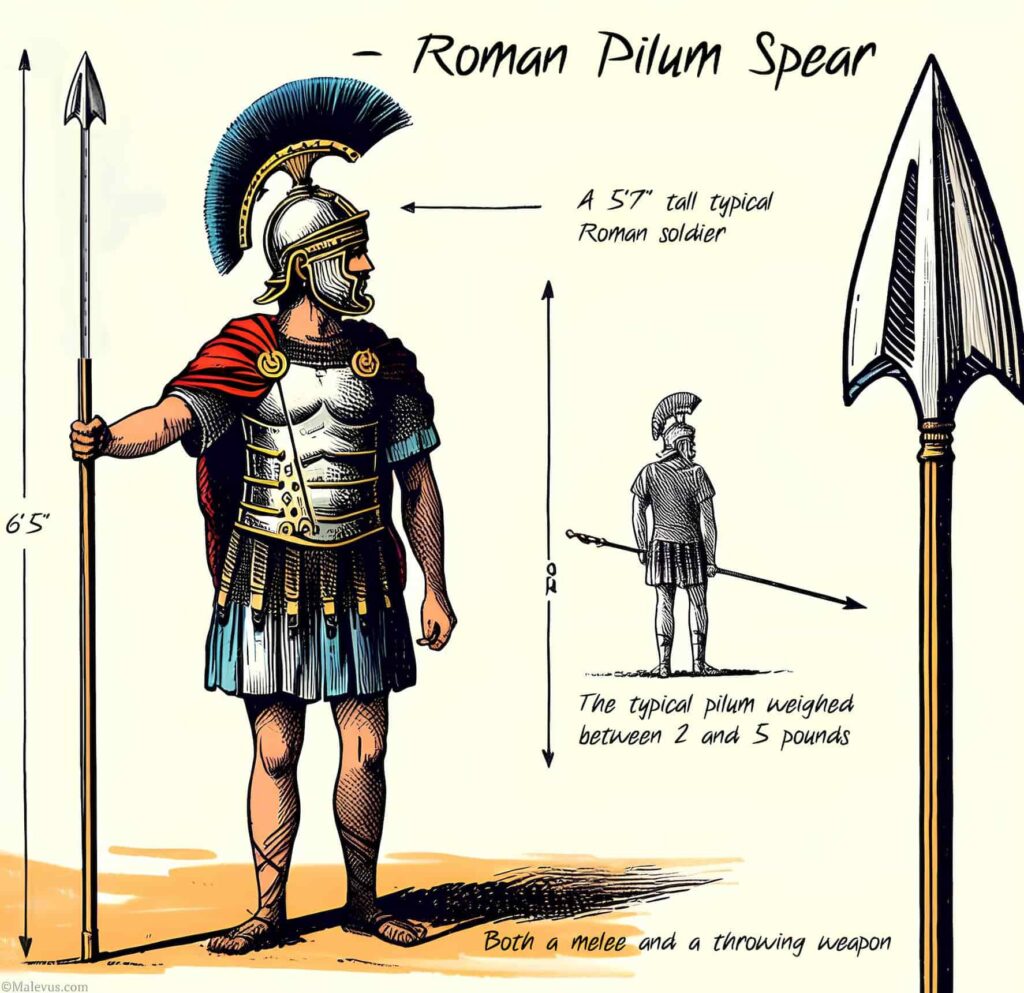

Each man had to protect himself with a scutum (shield), and his armament included two pila (spears). The pila were of two kinds – heavy and light. Some heavy pila were round with a diameter of a palm’s length, while others were square. Each was equipped with a head with backward hooks of the same length as the shaft. The head was firmly attached to the shaft with several rivets, so that in action, the iron cracked before it separated, although at the point of contact with the wood, it was one and a half fingers thick; such great care was taken in its secure attachment. — Polybius

The Hastati and Principes were primarily armed with the gladius hispaniensis, a sword described by Polybius as excellent, sharp, and strong. The gladius was likely adopted from the Spanish Celtiberian tribes after the Second Punic War. It was forged from iron, with a blade measuring 20 inches in length. Its long point suggests it was used for thrusting, which is more effective than slashing. Roman maniples provided more space than tight Greek phalanxes, resulting in a diverse mix of individual combat in battles. In this way, the Romans often emerged victorious due to the outstanding performance of individually well-trained fencers.

Roman Empire Infantry

The first Roman Emperor Augustus, like his great uncle Caesar, recognized that military success greatly contributed to political popularity. Therefore, a cautious expansion policy alternated with the improvement of the empire’s defense. This trend continued until the Germanic leader Arminius destroyed three Roman legions in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD. Augustus discouraged his successor Tiberius from aggressive wars, yet further conquests occurred. In 43 AD, Emperor Claudius ordered an invasion of Britain, and between 100 AD and 115 AD, Emperor Trajan conquered Dacia (modern-day Romania) and Mesopotamia. Trajan’s successor Hadrian adopted a passive defensive policy.

The strategy of the Roman Empire required only a small professional army. In 31 BC, there were 60 legions, but Augustus reduced them to 28 legions composed of long-serving volunteers. The traditional sixteen-year military service from the times of war became the minimum for conscripts. The property ownership requirement was completely abolished, allowing any Roman citizen who passed the selection process to join the army. Each legion was led by a legate (a senator appointed directly by the emperor) and six tribunes. The organization resembled that introduced by Gaius Marius. Therefore, ten cohorts consisted of six centuries of 80 men each, with the first cohort expanding to 800 men with an extra century.

The equipment of the legionaries underwent limited development. They used the pilum, with a design similar to the Republican era but significantly lighter, until around 200 AD. The sword was shortened, with a blade of approximately 20 inches, indicating a purely thrusting weapon. Legionaries wore mail armor until the end of the 1st century, when it gradually gave way to the distinctly Roman lorica segmentata, armor made of iron strips connected by hooks, straps, or bands. Around the same time, the original oval shield called scutum was replaced by a rectangular shield made of layers of wood covered with leather, with its sides protected by a bronze sheet. Regarding helmets, there was minimal uniformity, with the Gallic helmet being the most commonly used, named so because armorers in Gaul crafted it.

-> See also: Lorica Hamata: The Roman Chainmail Used For 600 Years

Auxiliary Forces

The Roman legions constituted the main striking force of the Roman army, facing the greatest threats. The responsibilities of barracks work and voluntary operations fell on the shoulders of auxiliary forces; these auxilia were comprised of non-Roman citizens and subjects of the Roman Empire. Auxiliary forces further supported legions in larger conflicts. Auxilia consisted of conscripts from tribes, mercenaries, or allies; since the time of Emperor Augustus, there were at least 70 cohorts of auxiliary infantry units composed of long-serving professionals organized similarly to legionary cohorts.

Each auxiliary cohort was recruited from a specific province of the Roman Empire, and its name indicated the province of origin. However, from the late 1st century AD onwards, cohorts were often assembled elsewhere, and conscriptions from new areas led to great diversity in their ethnic composition. The main incentive for conscripts was the prospect that after completing 25 years of service, Roman citizenship with full rights would be granted to auxiliary forces and their descendants. Cohorts were composed of archers, slingers, or heavy infantry. The equipment of auxiliary forces lagged behind that of legions by at least one generation.

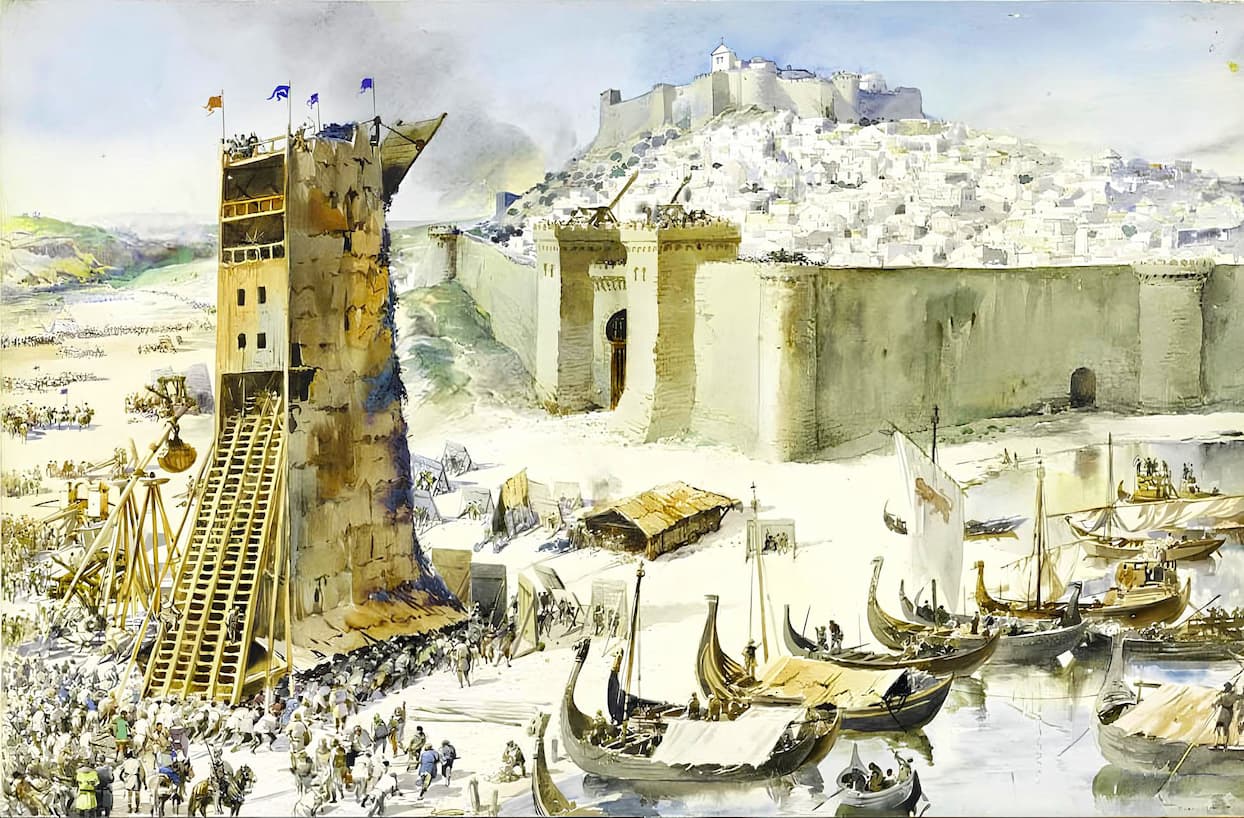

Tactics of the Roman Empire Army

During the early Roman Empire, large-field battles were not too frequent. Instead, there were campaigns against insurgents, typically concluded with legionary attacks against their fortifications. Military campaigns became more of a routine logistical and technical matter than a tactical problem. This period is characterized by a doctrine that relied on the formidable power of ranged weaponry. In 68 AD, future Emperor Vespasian besieged the Jewish city of Jotapata (Yodfat), initiating daily attacks with bombardment involving at least 350 missile throwers and 700 archers.

When his son Titus conquered Jerusalem two years later, he likely had the support of 700 missile throwers. The importance of ranged firepower in field battles continued to grow; against the Alans in 135 AD, Arrianus deployed his two legions behind a wall of overlapping shields, with two rows of archers and missile throwers standing behind the protective barricade formed by the legions, shooting down the Alan cavalry. Under the protection of ranged firepower, legions attacked fortified positions and sometimes used special formations. The most famous of these is the “testudo” (tortoise). This formation reflects the level of training in the Roman Empire army, as its execution required very intensive training.

The Decline of Roman Infantry

From the mid-2nd century AD, the primary external threats to Rome were the barbaric Germanic tribes. The decline in the effectiveness of the Roman army was a result of the expansion meant to counter the barbarian threat. Military service became mandatory, a highly unpopular move that contributed to the decline of the army. It was offset by the conscription of barbarians, leading to the barbarization of Roman weapons and tactics. The tactical advantage achieved through professionalism—the excellent equipment and tactics of legions from the time of the Republic and the early Roman Empire—was eventually sacrificed for strategic considerations.

The main weapons of Roman infantry included the spatha sword, a dagger, a heavy spear called the spiculum, which could be thrown or thrust, and a lighter javelin known as the vericulum. The spatha was a slashing sword with a blade length of 28 inches, likely derived from the Gallic longsword and used by cavalry in the Augustan period.

Many infantrymen of that time ceased wearing armor, even helmets, which proved to be a significant disadvantage when facing the Goths, who accompanied their raids with a hail of projectiles, and later against the Hunnic mounted archers. The armor consisted almost exclusively of helmets. The helmets bore signs of unskilled mass production, unable to meet the needs of the new conscript army. Ranged firepower was formidable and likely aimed to prevent barbarians from getting within reach, where their size and ferocity could decide the outcome of the battle.