What did Jan Ingenhousz discover about photosynthesis and how did he make this discovery?

Jan Ingenhousz discovered the process of photosynthesis, which is the process by which plants convert light energy into chemical energy in the form of organic compounds. He made this discovery through a series of experiments in which he demonstrated that plants release oxygen in the presence of light. This led him to conclude that plants were using light energy to produce oxygen and that this process was critical for their growth and survival.

What other contributions did Jan Ingenhousz make to the field of plant physiology?

In addition to his work on photosynthesis, Jan Ingenhousz made several other significant contributions to the study of plants. He conducted experiments on the respiration of plants, and he was the first to recognize the importance of air circulation in the prevention of plant diseases. He also conducted research on the movement of fluids in plants, which laid the foundation for the development of modern plant physiology.

How did Jan Ingenhousz’s work on plant pathology contribute to the development of modern agriculture?

Jan Ingenhousz’s work on plant pathology helped to lay the groundwork for the development of modern agriculture by demonstrating the importance of disease prevention and control in the cultivation of crops. His research on the movement of fluids in plants also helped to improve our understanding of how nutrients are transported within plants, which has implications for crop yield and quality.

What was Jan Ingenhousz’s relationship to other prominent scientists of his time?

Jan Ingenhousz was a contemporary of several other prominent scientists of his time, including Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Priestley, and Antoine Lavoisier. He corresponded with many of these scientists and shared his findings with them, and his work on photosynthesis and plant physiology was influential in shaping the scientific community’s understanding of these subjects.

Who is Jan Ingenhousz? Charles Reid Barnes first used the term “photosynthesis” in 1893. But it was Jan Ingenhousz who first discovered and described the fundamental properties of this chemical process a century earlier. In the summer of 1779, Dutch physician Jan Ingenhousz conducted more than 500 detailed experiments at his country house near London and described his findings in Experiments on Vegetables. When his discovery was called “photosynthesis,” the name of the discoverer was long forgotten. Today, he reappears through the mists of time.

Indeed, Ingenhousz was not only a brilliant experimenter, a gifted medical doctor, and a prolific researcher in chemistry and physics, but also a critical examiner and a multilingual traveler.

Who Was Jan Ingenhousz?

Jan Ingenhousz was born in Breda, near the border of what is now Belgium and the Netherlands. As a Catholic, he was denied admission to Protestant universities in his home country, so he crossed the border to Louvain to study medicine. After graduation, he satisfied his curiosity and specialized in courses in gynecology, physiology, agriculture, chemistry, and pharmacology in Paris, Leiden, and Edinburgh. After his father died, he went to England because Sir John Pringle asked him to. He left his growing medical practice in his home city.

Pringle knew the young and talented Ingenhousz from his time with the British army on the European continent. Pringle was now the well-known author of Diseases of the Army and King George III’s court physician. He introduced Ingenhousz to London’s scientific and political elite. One of them was Benjamin Franklin; he and Ingenhousz became lifelong friends and partners in scientific endeavors.

In 1766, Jan Ingenhousz participated in a campaign to vaccinate the population against the deadly smallpox epidemic using a live smallpox virus. It was one of the first effective attempts at disease prevention in medical history. Although it was met with considerable resistance, especially in religious circles, it also attracted the attention of the enlightened elite in Europe. Empress Maria Theresia of Austria invited Ingenhousz to visit Vienna to treat her family. The treatment was successful, resulting in Ingenhousz being appointed royal physician and receiving an annual salary for the rest of his life.

Now wealthy and independent, he traveled throughout Europe, living in London, Paris, and Vienna, and meeting European intellectuals, politicians, and natural philosophers. Meanwhile, he spent long periods at the Wiltshire estate of the Earl of Sherburne, where Joseph Priestley’s laboratory is located and where he discovered oxygen in 1774. Jan Ingenhousz was elected to the Royal Society in 1779 but declined most invitations from other societies. He even turned down an imperial request to head all the universities and libraries in Austria. His fiery criticism of the charlatan Anton Mesmer was a by-product of his relentless quest for reliable knowledge and led to the expulsion of this inventor of “animal magnetism” from Vienna.

The Mysterious Life of Plants

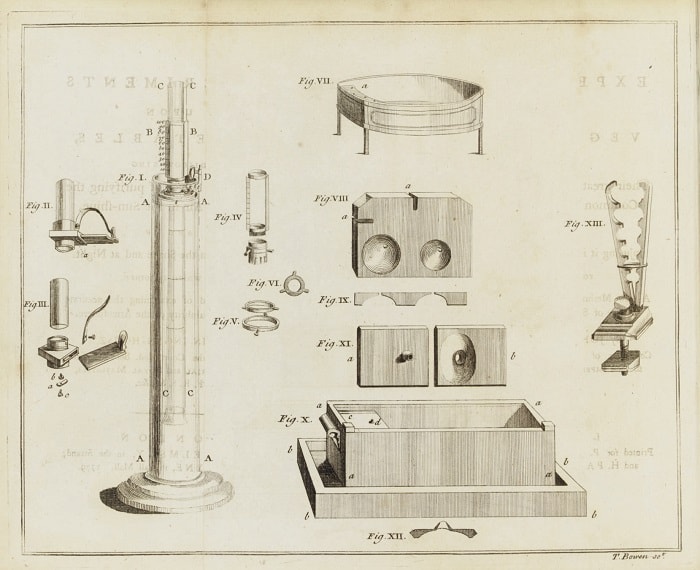

Above is the plate from Experiments on Vegetables describing the audiometer. This instrument was, in Ingenhousz’s words, “a new method of examining the accurate degree of salubrity of the atmosphere.” “Nitrogenous air” (nitrous oxide) was mixed with an air sample in a glass flask over water. It reacted with the “phlogiston-free air” (oxygen) in the sample, giving off a red fume that dissolved in the water and thus raised the water level. The final water level indicated the amount of oxygen in the sample.

His pragmatic mind led him to optimize the design of the audiometer. This instrument, which literally “measures the salubrity of the air”, was conceived by Priestley and developed by one of Ingenhousz’s peers, Abbe Fontana. Not only did the instrument become embedded in the roots of environmental science, but it also allowed Ingenhousz to study the gas production of plants. As the title of Ingenhousz’s 1779 book suggests, he understood the essence of this unexpected plant mechanism: “Discovering their great power of purifying the common air in the sunshine and of injuring it in the shade and at night.”

To put this in modern terminology, plants produce carbohydrates via the hydrogen from the water and the carbon from the air. They get the energy for this process from the sun through the green molecular compound chlorophyll. The waste product of this process is oxygen, which gives life to all creatures, including us. With his experiment, Ingenhousz eliminated all unrelated variables and explained how plants—only the green parts—purify the air by producing phlogiston-free air (oxygen). By comparing the “air” around different plants in the dark, in the sun, and near the stove, he showed that the “salubrity of the air” was “enhanced” not by heat but by sunlight. He also showed that, like all other respiring organisms, they damage the air by producing a “fixed gas” (carbon dioxide). This was best observed in the dark, when oxygen production did not exceed carbon dioxide production.

The publication of his findings in 1779 sparked a lifelong controversy with Priestley, Jean Senebier, and Willem van Barneveld, who claimed to have discovered them first and tried to prove Ingenhousz’s claims wrong. But with his friend Franklin’s full support, Jan Ingenhousz decided to keep researching and practicing instead of getting into endless arguments.

Jan Ingenhousz’s Other Works

He went on to emphasize the vital role of plants in the organization of the earth. He talked about the “plant economy” and explained that it is the force that moves the earth’s ecosystem. With urgent agricultural needs, he experimented with methods of improving plant growth and was elected an honorary member of the Board of Agriculture in London in 1793. Ten years after his groundbreaking description of photosynthesis, in 1789, he changed the way he talked about how plants, sunlight, and the air interact by using Antoine Lavoisier‘s new chemical terms of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen as the photosynthesis ingredients.

Ingenhousz’s research on photosynthesis was just one of his many endeavors. In 1785, he described the use of the coverslip in the microscope and the random motion of particles in solutions, now known as “Brownian motion.” He studied and published on electrical conductors, machines, and guns; lightning rods and gunpowder; magnetism; the properties of metals; and flammable gas lamps. He was also very interested in the medical applications of new discoveries. He was the first to talk about electroshock therapy for psychiatric disorders. He contributed to Thomas Beddoes’ invention of pneumatic medicine by designing a device for the treatment of various diseases by inhaling oxygen.

In July 1789, he left Paris to escape the French Revolution and returned to London. Throughout his life, political unrest prevented him from traveling to Vienna and finding his wife. In his last years, he struggled at his drawing table to complete his many experiments and research projects. He corresponded with Edward Jenner, who was inoculating cowpox instead of smallpox, to make a final suggestion for evidence-based medicine. Jenner’s new technique showed promise, but Ingenhousz feared it would be dangerous to use without sufficient evidence of its safety. Jan Ingenhousz died at Bowood House in 1799. It is not known where he is buried in Calne Church.

References

- Geerd Magiels, Dr. Jan Ingenhousz, or why don’t we know who discovered photosynthesis, 1st Conference of the European Philosophy of Science Association 2007

- Ingen Housz JM, Beale N, Beale E (2005). “The life of Dr Jan Ingen Housz (1730–99), private counsellor and personal physician to Emperor Joseph II of Austria”. J Med Biogr. 13 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1177/096777200501300106

- Dr Jan IngenHousz,or why don’t we know who discovered photosynthesis? by Geerdt Magiel (PDF)