Famous for her role in French history, Joan of Arc (1412-1431) was also known as Jeanne d’Arc, Joan the Maid, or the Maid of Orleans. She was a peasant girl from Domremy, Lorraine, who supposedly received divine guidance telling her to save the king from the English and the Burgundians. She convinced King Charles VII to give her an army in 1429 by traveling to Chinon. She helped end the Siege of Orleans with a group of royal warriors and then took Charles VII to be crowned at Reims.

But the Burgundians seized her and sent her over to the English the next year. On May 30th, 1431, she was put on trial for witchcraft and executed by being burned at the stake in Rouen’s central market. The Catholic Church canonized Joan of Arc as a saint in 1920, after reevaluating the 1456 trial that brought her to prominence. She is a legendary character in French history, inspiring many works of literature and art and serving as the focus of various political comeback campaigns.

Who was Joan of Arc?

Since the 1400s, Joan of Arc’s narrative has been the subject of several interpretations and recoveries, resulting in a vast library that dwarfs that of any other renowned figure from the Middle Ages, including Charlemagne and Saint Louis. After a cursory examination of her classical life, the question of how she would be remembered historically appears more intriguing.

Most historians believe that Joan of Arc was born at Domrémy, a village dependent on Vaucouleurs and so near to the French Empire, on January 6, 1412 (though different dates are also put forth). In 1425, Joan, a member of a family of prosperous farmers, had her first voices. She was told by the saints of Bar, Michael, Catherine, and Margaret, the patron saints of the area, that she must visit the dauphin Charles and aid him in “driving” the English out of France.

In the letters, Joan emphasized her virginity by referring to herself as “Jeanne la Pucelle” (Joan the Maiden) or simply as “la Pucelle” (the Maiden), and she signed her name “Jehanne.” She gained fame in the 1600s as the “Maid of Orleans.”

Though there were many prophets and prophetesses active in the time period, Charles VII welcomed her in March 1429. The Duke of Alençon, who had come to believe in Joan’s divine purpose, had the girl undergo both a medical and a theological examination at the suggestion of his advisors. Without a hitch, Joan breezed through both tests. King Louis listened to his court and consented to dispatch the Pucelle (Joan’s other name) to lift the siege of Orleans, even though he did not seem to have fully fallen into the extremely voluntary messianism of Joan.

Joan predicted that Charles would become king and that Paris would be taken back. In spite of certain French captains’ skepticism about Joan’s unorthodox “tactics,” the siege of Orleans was successfully lifted on May 8, 1429. Later triumphs followed, including the one at Patay (18 June 1429), and Joan ultimately succeeded in convincing her king to invade Burgundy in order to be crowned in the cathedral of Reims. On July 17, 1429, this action was taken.

Joan’s situation got increasingly difficult. Charles VII increasingly distanced himself from her under the influence of Georges de la Trémoille when she failed and was wounded in front of Paris, casting doubt on the veracity of her prophecies. Joan and her family were nobly elevated at year’s end in 1429, but she was soon given menial tasks and eventually sent to Compiègne on May 23 of the following year. She was tricked into a trap on the 23rd and sold to the English. After a highly politicized trial presided over by Pierre Cauchon, Joan of Arc was found guilty of heresy, relapse, and idolatry and executed by burning on May 30, 1431. The French monarch made no serious effort to get her back. To prevent a cult from forming, Joan of Arc’s ashes were dumped into the Seine.

Joan of Arc, between history and legend

By the late 15th century, Joan of Arc had already entered the annals of history as a figure of mythology. National heroine, she served under the Third Republic for the revanchist cause of the “blue line of the Vosges.” Since 1920, when she was canonized, she has been revered as a holy figure. When considering the significance of this narrative in French history, it is hard to overstate how vital it is. The first miracle would be that she was able to overcome the reluctance of Charles VII and arm herself against the English army while she was only seventeen years old (she was born in 1412). Her parents are well-to-do peasants.

Only two trials, Joan’s condemnation trial at Rouen in 1431 and her rehabilitation trial, which Charles VII consented to open in 1456 at the request of Joan’s mother Isabelle Romée, exist to provide historical context for the story. With her defenses up, Joan’s word is skewed, and the accounts of her contemporaries are heavily colored by myth. Historians have the responsibility of calculating Joan’s debt to and contribution to her era.

Despite being disproven nearly a century ago, the theory of “bastardy,” which claims she is the illegitimate daughter of Isabeau of Bavaria and Louis of Orleans, persists with remarkable tenacity among sensationalists. While accusations of witchcraft served the English well, evidence reveals that some people, notably Rouen’s judges, theologians, and jurists, really held such beliefs.

It is heresy to cut ties with the militant Church in favor of hearing God’s message via the intercession of Saint Margaret and Saint Michael. For a layman at the turn of the fifteenth century, to partake in frequent communion was to defy the conciliar commands and thereby break with the church.

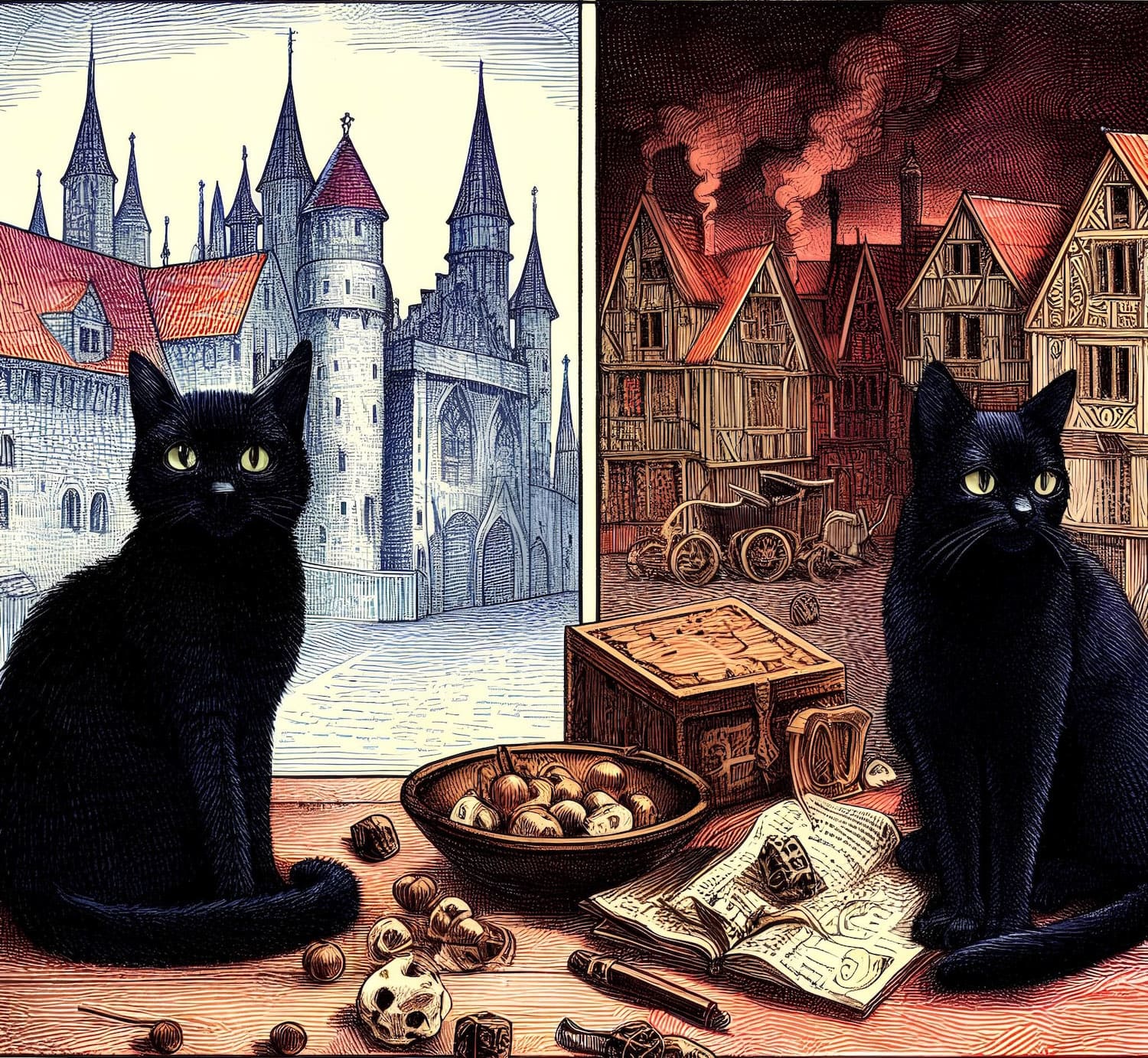

Domrémy’s proximity to the Empire’s borders heightened the already present sense of nationality. People struggled to protect the fleurs-de-lis from a pretend duke because they only had one king in their hearts. Ideas that speak to the resilience of Mont-Saint-Michel and the power of the coronation that spread among the people there. Joan of Arc then departed to “reveal” her mission to the king, following in the footsteps of earlier female prophets who had done the same for male monarchs. The difference this time was that Joan became a national icon.

The English recognized her symbolic value

One of Joan of Arc’s distinguishing features is that she stirred up emotions even while she was alive. Indeed, the English (the Duke of Bedford in the lead) and the Burgundians accused her of being a witch, while Jean Gerson and Christine de Pizan praised her. Thus, she earned the moniker “the whore of the Armagnacs” (because Robert de Baudricourt, commander of her local châtellenie, belonged to the Armagnac faction).

The symbolic value of Joan of Arc was immediately recognized by the English, who purchased her from Jean de Luxembourg for 10,000 livres and moved her to Rouen, the capital of seized France, to be tried by an ecclesiastical court. In the same vein as touching on the validity of its ruler, Charles VII, by having the populace believe in a religious trial while, in reality, it is mostly a political one, is the myth of Joan of Arc. Despite the trial and the subsequent dispersal of the ashes, the tale persists.

Since no corpse was ever found after the events of May 30, 1431, proponents of the theory that Joan was still alive and well swear to her being “not dead” at Rouen on the basis of the appearance of three imposter Jains between 1436 and 1460. The king has mastered the art of capitalizing on the legend of the person who approved his coronation and therefore confirmed his right to the throne. After the Armagnacs and Burgundians had made peace at the Treaty of Arras, he had Joan put on trial for rehabilitation and framed her actions in the context of a war against a foreign power (1435).

The death of Charles VII, however, began Joan of Arc’s steady decline into obscurity, even though she was still praised by François Villon or in the Mystères (a dramatic genre) towards the end of the 15th century. And this is hardly the moment in which to honor a medieval prophetess…

“Idiot” and “pious deceit” for Joan of Arc

True, the Ligueurs did a nice job of rehabilitating Joan of Arc for a while in the 16th century, but the Renaissance and the Enlightenment were not sympathetic to anything remotely “Middle Ages,” and so her reputation suffered.

Both Joachim du Bellay and Girard Haillan saw her as little more than a tool of the court, and the latter even cast doubt on her virginity. Voltaire called her an “unfortunate idiot,” a victim of the monarch and the Church, while Montesquieu found only “pious duplicity” in her, but the most violent were the thinkers of the Enlightenment. It wasn’t until the 19th century that Joan reappeared, this time as a cultural figure rather than with an air of holiness.

The romanticism of the 19th century, which was more receptive to medieval and “Gothic” motifs than the enlightened Enlightenment, helped revive the tale of Joan of Arc.

The most iconic example is perhaps Jules Michelet, who in 1856 wrote in his signature manner, “Let us always remember, Frenchmen, that the fatherland among us was born from the heart of a woman, from her compassion and her tears, from the blood she bled for us.” Joan of Arc personifies the common folk: strong and uncomplicated. One of the most potent tools used to build the national republican novel and the myth was Joan of Arc. No one anticipated that the prophetess would one day be revered as a cultural symbol.

The Holy Joan of Arc

The Church’s reacquiescence in Joan’s case was indirectly encouraged by Jules Quicherat, a Michelet student. And he was an anticlerical historian that he uncovered these primary documents in the 1840s, publishing them for the first time. The historian Quicherat “charged” King Charles VII with abandoning Joan of Arc and called the Church an “accomplice” in his prologue. It was the work of German historian Guido Görres (The Maid of Orleans, 1834) that spurred two Catholic historians to attempt a recovery of Joan.

In 1860, Henri Wallon released his biography of Joan of Arc. For him, Joan is a saint and a martyr; he emphasizes her devotion but acknowledges that she was actually abandoned. Wallon reaches out to Monseigneur Dupanloup in an effort to enlist his support in the cause of canonizing Joan of Arc. During a time of dechristianization and crisis of faith, Bishop of Orleans Félix Dupanloup felt it was crucial for the Church to use powerful symbols. Specifically, in 1869, he wrote a panegyric praising Joan of Arc and formally advocated for her canonization.

In addition to her continuing popularity and republican icon status, the political climate of the second half of the nineteenth century played a significant role in the Catholic recovery of Joan of Arc. The first major shift occurred in 1878, on the occasion of Voltaire’s centennial. Anyone who could call Joan an “idiot” and the Church as a whole would understand why Catholics would dislike this guy. As a protest against the philosopher’s glorification, the Duchess of Chevreuse urged all French ladies to bring flowers to the Place des Pyramides and place them at the feet of the monument of Joan of Arc.

The anti-clerical Republicans, who didn’t want to give up on their party’s symbol, organized a counter-protest. Nothing happened because the prefecture forbade both. This, however, marked the beginning of a serious reappropriation of Joan by conservative Catholics. A nationalist right that wanted its own Joan of Arc emerged in the wake of the Dreyfus Affair (1898) and the subsequent Boulangist crises of the 1880s. Last but not least, the response of the Pope was significant; he reopened her trial in 1894, and Joan of Arc was beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920. The Catholics, and especially the nationalist right and extreme right, reclaimed Joan of Arc.

The nationalist heroin

This Joan was progressively forgotten by the Republic over the 20th century and into the 21st, while being glorified by nationalists and the far right. Nationalism, anti-Parliamentarianism, royalism, and Catholic fundamentalism, all tinged with anti-Semitism, overwhelm Joan of Arc.

After the Dreyfus case, the extreme right adopted Joan as their mythological anti-Jewish character. She had to be the one to preserve not just the military’s traditions but also the established order. To commemorate the 500th anniversary of the liberation of Orléans, a postcard was postmarked with the words “Joan of Arc against the Jews” in 1939. The emblem was clearly also adopted by the Vichy dictatorship.

After the war, both De Gaulle and the Communists hailed Joan, and by the end of the 1940s, she seemed to have returned to the Republican fold. But that influence eventually died down, and it wasn’t until Jean-Marie Le Pen revived Marian cults in 1988 that the Virgin Mary was once again used as a symbol of French nationalism. Despite left-wing protests, Joan of Arc eventually became a footnote in French history, with little to no mention in official textbooks, despite scholars still agreeing on her significance.

During her lifetime, Joan of Arc was mostly regarded as a myth, and she was quickly the subject of political and religious recuperation, neither of which helped historians. Because of this, it is difficult to determine who Joan of Arc really was; yet, it seems to have been established that her part in the events of the Hundred Years’ War was incidental. It wasn’t until later that she became really significant. Although she may not generate the same level of excitement as she once did, the constant stream of hypotheses about her, some of which are more plausible than others, demonstrates that she continues to pique the public’s curiosity.

THE TIMELINE OF JOAN OF ARC

Joan of Arc was born on January 6, 1412

Domremy, France, was the birthplace of the French heroine Joan of Arc, sometimes known as “the virgin.”

Beginning on January 1, 1425, at the age of 13, she started to hear voices

She hears voices for the first time. She claims that God and the archangels Saint Michel, Saint Catherine, and Saint Marguerite are behind these sounds.

In 1429, on April 29, Joan of Arc arrived in Orleans

Joan of Arc, a young lady from Lorraine, led an army into Orleans, claiming to have been sent there by God to declare Charles’s royal legitimacy and to expel the English from France. Since October 1428, the city has been under English siege. On May 8, 1429, Charles VII’s last army conquered the city of Orleans, and on July 17, 1429, Charles VII was crowned at Reims under the direction of Joan of Arc. Afterward, he was prepared to retake the country and restructure royal authority.

The coronation of Charles VII took place on July 17, 1429

Charles VII was crowned in Reims Cathedral with Joan of Arc present.

In Compiègne on May 23, 1430, Joan of Arc was taken into custody

Captured by a mercenary serving the Duke of Burgundy, Jean de Luxembourg, Joan of Arc was then sold to the English for 10,000 livres, despite having played a pivotal role in the liberation of Orleans the previous year. In 1431, she was prosecuted for heresy at the Inquisition Court in Rouen and executed by burning at the stake, even though she was not provided any legal representation. In 1456, she was rehabilitated.

The trial of Joan of Arc started on January 9, 1431

Joan of Arc, accused of heresy, was tried by a court at Rouen presided over by Pierre Cauchon, bishop of Beauvais. On February 21, at the royal chapel of Rouen Castle, the first open session began. On May 24, she publicly repented and admitted her faults, but by May 28, she had reversed her decision. On May 30, at Rouen, on the Place du Vieux-Marché, Joan of Arc was burned to death.

It was on May 30, 1431, when Joan of Arc was publicly executed

Rouen’s Place du Vieux-Marché (Haute-Normandie) is where Joan of Arc was burned to death for her “relapse” (return to heresy). The high stake prevented the executioner from suffocating Joan of Arc before the flames reached her. Two years earlier, in 1429, Joan of Arc had successfully freed Orleans from the English siege and had Charles VII crowned at Reims. But the Burgundians captured her at Compiègne and sold her to the English. The monarch made no overt attempt to save her.

Joan of Arc was canonized as a saint on January 1, 1909

After her death, Joan of Arc was elevated to sainthood.

On May 16, 1920, Benedict XV officially declared Joan of Arc a saint

The Catholic Church officially recognized Joan of Arc as a saint.