Sometimes great scientists make their greatest discoveries while they are working with a partner. This was true for Marie Curie and Pierre Curie, who complemented each other’s work in their research on radioactivity, and also for Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey, who pioneered research on the origins of man in East Africa. The Leakey team worked together on numerous research projects and excavations, which established the “Leakey” name as a prominent figure in the field of human evolution studies. Their work conclusively established that the origins of humankind can be traced back to Africa. Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey traced the origins of the human lineage over a period spanning 18 million years to learn more about the ape-like ancestors of Homo sapiens. They discovered the first human being to make a tool, called Homo habilis, and named it “Jonny’s child.”

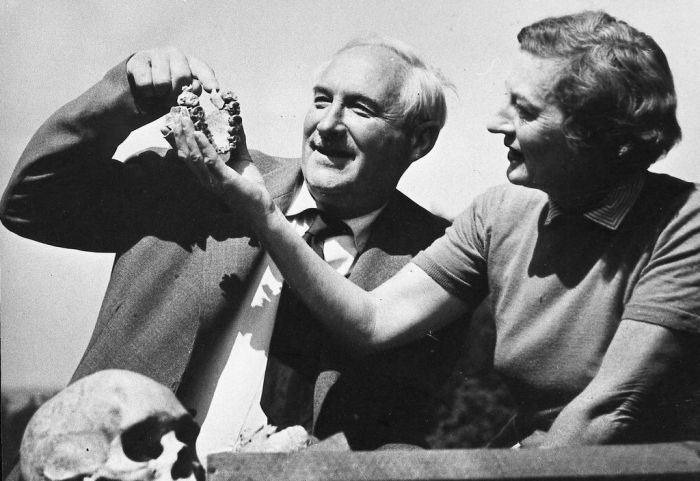

Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey

The couple also made independent discoveries. Mary found fossil footprints that show the first humans walking upright three million years ago—about a million years before our ancestors started making tools. The visionary Louis helped launch the first long-term field studies of wild primates by sending Jane Goodall to record chimpanzee behavior, Dian Fossey to observe mountain gorillas, and Birute Galdikas to observe orangutans. These studies helped shape our understanding of the social lives and cultures of our early ancestors. Together, Louis and Mary turned paleoanthropology from a simple study of rocks and bones into the complex and rich field it is today.

Although it was Mary Leakey who made many of the most important discoveries, Louis Leakey was the person who fueled the work. Louis Leakey’s idea to seek out the origins of humanity in Africa, disregarding the prevailing scientific consensus, was the driving force behind their expedition. At the time, paleoanthropologists believed that humans migrated to Africa after evolving in Europe and Asia. Louis proved this idea wrong, and over time, with Mary’s contributions, he completely ruled out the old belief.

Louis’ bias in favor of Africa was partly due to his origins. His parents were missionaries who lived with the people of Kikuyu in a village in the mountains above Nairobi, in British colonial East Africa (now Kenya). Although his parents were English, Louis always saw himself more as a Kikuyu. He was the first white boy born among the Kikuyus, and they accepted him into their lives. When he was 11, he joined the secret reception ceremony of the tribe with other children his age and became a member of the Mukanda.

His parents had hired a teacher for his two older sisters, his brother, and himself, but he eventually did not receive a regular education. Louis had plenty of time to participate in even more interesting events and adventures with the Kikuyu blood brothers. He learned their language and how to hunt with a bow and arrow, make traps, trace, and even hunt animals with his bare hands. Louis Leakey attributed his unique insights and perspectives on early humans and human evolution to his traditional Kikuyu education.

Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey: Exploring ancient Africa

However, it was the book his cousin gave him for Christmas that took him on this professional path. The book Days Before History was about the adventures of an English boy named Tig who lived in the Stone Age. The book included illustrations of the Stone Age peoples and the tools they created, with dates on them. Louis began collecting glass rocks inspired by the book, which he discovered in eroded carvings along streams near his home. His family made fun of his “broken bottles,” but Louis had an independent streak.

He then consulted the only scientist he knew, Arthur Loveridge, the curator of the small natural history museum in Nairobi. Loveridge studied the finds and determined that some of them were indeed “tools,” but also explained to Louis Leakey that there is still much unknown about the Stone Age in Africa. These words changed Louis’ world; now he had research to pursue his entire life. In his autobiography, White African, he writes, “I definitely decided to go down this road until everything about the Stone Age [in Africa] was known.” He had just turned 13 years old.

It was not easy for Louis to pursue his desired career. His schooling was limited to the few years he attended school in England during his off days, but he managed to close this gap by working hard and was accepted into St. John’s College, Cambridge. After earning a dual bachelor’s degree in anthropology and modern languages (one was Kikuyu), he received a small research scholarship.

On this scholarship, he bought a ticket for a ship to Kenya and organized the first East African archaeological expedition in the summer of 1962. One of the Cambridge professors tried to dissuade him by saying that he would waste his time looking for the first humans in Africa because “everybody knows they originated in Asia.” Such negative remarks made Louis even more determined to find the evidence he is looking for and prove the professor wrong.

Eventually, Louis led four separate voyages to East Africa. On each, he uncovered further evidence of the continent’s obscure ancient epochs, such as bone fragments and prehistoric stone tools, that shed light on a time period that few scientists had ever considered. He was particularly interested in discovering stone hand axes from the Chellean (Abbevillian) civilization, named after those unearthed in the French town of Chelles. Large, oval-shaped hand axes were formerly seen as evidence of the world’s first civilization by archaeologists.

Louis Leakey and his axe

On the team’s second expedition, John Solomon, the team’s geologist, found such a hand axe in 1929 at the site called Kariandusi. He wasn’t sure what he found was a hand axe, but Louis made the correct diagnosis as always. He sent Solomon and a student to find more of these, which they did. In those days, there was no method for dating the geological layer where fossils and ancient man-made remains were found.

Geologists often estimated the age of such objects by measuring the depth of the sediments surrounding them, which were assumed to accumulate at a constant rate. Using this approach, Louis estimated the hand axes to be at least 50,000 years old. Later, more precise dating tools were used, and scientists found that hand axes were actually as old as 500,000 years.

Discovering tools in Africa that were at least as old as those in Europe was thrilling, and Louis had the funds to undertake his biggest expedition yet. In 1931, he set out for Olduvai in the Tanganyika District (now Tanzania). In the Rift Valley, the 25-mile (40-km)-long Olduvai Gorge meandered deep along the Serengeti Plateaus. German geologist Hans Reck surveyed the valley in 1913 and found an abundance of extinct mammal bones as well as modern human bones. Reading Reck’s report, Louis thought that although Reck did not find any stone tools in the valley, the geologist had overlooked them.

He invited Reck on an expedition. With four vehicles and a crew of eighteen people, they traveled overland, following the footsteps of Indian traders who had crossed Nairobi for three days, but the trail ended at some point. They then advanced about five miles (eight kilometers) an hour over two days and finally reached the border of the Olduvai Gorge on the morning of September 27. A little after dawn the next day, Louis walked on his own across the valley and found a hand axe. The feeling was enrapturing. He quickly ran to the camp with an axe in his hand and awakened others to share his joy.

Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey’s love

Louis met Mary after his expedition. Mary (Douglas) Nicol, as she was called at the time, was a young artist and a promising anthropologist. Louis was married, had a daughter, and his wife was pregnant. He was also truly broke. He had an income from anthropology and his lectures at St. John’s but felt he could get some funding with his popular book, Adam’s Ancestors, in which he described his discoveries. He needed someone to make drawings showing the stone tools, and a friend introduced him to Mary at a dinner party.

The daughter of a landscape painter, Mary grew up traveling in Italy, Switzerland, and France. Like Louis, she was struck by archeology as a child. A French archaeologist had guided her and her father through the rooms of the prehistoric Pech Merle Cave with murals and allowed them to search for stone tools in the excavated deposits. This trip lit a fire in her heart. “After that, I really never wanted to do anything else,” she said.

Mary was also not properly educated. After the sudden death of her father, her mother sent her to a convent school, but she managed to be expelled from school by pretending (she had put soap in her mouth) and causing an explosion in the chemistry class. “The explosion was quite noisy, a lot of nuns came running, it must have been good for some to run,” she said about the incident. She then volunteered for many excavations and attended archeology and geology lectures at University College London and the London Museum.

At the age of 20, she was unconventional, artistic, playful, and a glider pilot with a passion for French cigarettes. Whether she explained all this to Louis at their first meal is unknown, but they found each other very attractive and soon fell madly in love.

Louis invited her on his fourth (and final) East African archaeological expedition. He was returning to Olduvai in January 1935. This time they followed a new route, the long, muddy road to the summit of the Ngorongoro Crater and then the dark, narrow gully lines. There were herds of animals—elephants, zebras, rhinos, and buffaloes—on the plateaus, and Mary fell in love once again, this time with Africa.

Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey’s first discoveries

Louis and Mary were looking for stone tools and well-preserved fossils of animals that are no longer alive in the gully. They found numerous hand axes and more primitive tools that they later called the Oldowan culture (now known to be 2 million years old, the oldest man-made objects in the world). But they could only find two bone fragments from the first human skull.

It took 21 years before Louis was correct about the origins of humanity. During this time, he was divorced from his wife, married Mary, and had four children, three boys and one girl, but their daughter died in infancy. They settled in Nairobi, and Louis became the director of the museum where he first encountered his mentor, Loveridge. They spent all their spare time and every penny searching for bones and stones at sites in Kenya and Tanzania.

Sometimes they found surprising things. In 1942, in the Olorgesailie of the Rift Valley in southern Nairobi, they found a path literally paved with hand axes, as if the first humans once owned a factory to produce them. In 1948, on Rusinga Island in Lake Victoria, Mary discovered the skull and facial bones of an ancient but well-preserved 20-million-year-old ape, the Proconsul; it was the first such ape face to be discovered.

They found these fossils with the financial support of a London-based American businessman, Charles Boise. The businessman continued to provide them with small funds for expeditions, and in 1959, in Olduvai, finally, the financial support and the couple’s perseverance paid off. Mary Leakey made a discovery again. She went out alone while Louis was lying ill in the camp, and she slowly began to stroll down the rocky slope at the bottom of the gully. Around 11 o’clock, she noticed a piece of bone that stuck out of the ground rather than just standing on the surface. It looked like a piece of skull. She carefully brushed the soil above it and saw two large teeth on the jawbone. She immediately jumped into the Land Rover and drove frantically towards the camp.

“I found it. I found it. I found it.” Louis asked, “What did you find?” “Him, the man! Our man. The man we were looking for. Come now, I found his teeth!” Louis quickly pulled himself together and the two of them went to the site together. Mary was right: They had finally found the man they were looking for. Louis first named the skull Zinjanthropus, after the East African word for “man.” But it was later classified as a hefty form of Australopithecus, the hominin found in South Africa. Mary and Louis simply called it “Dear Boy.”

After the “Dear Boy,” Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey became famous. With new dating techniques, geochronologists were finally able to determine the age of the fossils at Olduvai. It proved to be “very, very, very old,” as one of the Dear Boy’s scientists told Louis. In fact, the skull was 1.75 million years old, tripling the initial assumption. It was a discovery that shook the world. The discovery made headlines around the world and sparked an anthropological rush to East Africa by scientists in an attempt to make a claim. The American paleoanthropologist Clark Howell, a colleague of the Leakeys, explained that the discovery of Zinj started the era of scientific research into human evolution.

Leakeys started full-time excavations in Olduvai with funding from the National Geographic Society. Mary led these excavations, assembling a team of Kamba workers, many of whom would be famous fossil hunters in their own right. Excavations were often family business; Louis, Mary, and their sons Jonathan, Richard, and Philip worked together. It was Jonathan who first found the bone fragments of the new human ancestor. Louis and Mary believed that Homo habilis was the hominid who made the oldest, most primitive tools for carving.

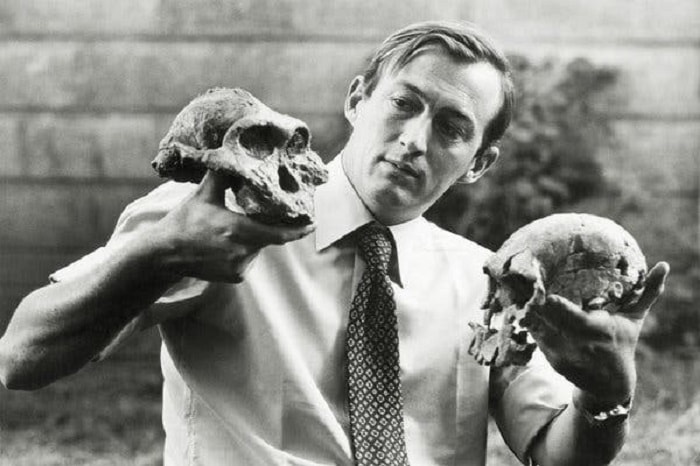

From the very beginning, Homo habilis has been the subject of debate. Being an organism different from the Dear Boy would mean that the two hominin species—the first upright, bipedal humans—lived on the African savannah at the same time. Louis argued that this possibility was very significant; by looking at other animals, it could be seen that a large number of antelope and primate variants lived together. But most contemporary scientists strongly criticized this branched family idea; they expected a long and linear human line, but it was never going to be the case.

3 million-year-old footprint

Then came the sought-after proof: Leakey’s middle son, Richard, went on his hominin hunt expedition around Lake Turkana in Kenya. Here they found the same footprints; two different hominin species lived side by side, one with thicker bones and the other with a larger brain but slender bones. “They won’t believe you.” That’s what Louis said when Richard gave him the Homo habilis skull.

But over time, they believed him. Today, paleoanthropologists draw many different human lineages, and they are all very branched. Louis Leakey died of a heart attack in 1972, a week after seeing Richard’s Homo habilis skull. He was 69 years old. Mary Leakey continued her excavations at Olduvai. Her team unearthed many fossils and thousands of stone tools. She mapped all of them in great detail, creating an almost 2 million-year-old record of the animal and human habitats that nestled in the gully.

In 1974 she turned her attention to another site, Laetoli, where fossils older than Olduvai had been found. This is where one of the team members spotted a very old set of footprints in 1978. These were the footprints left by three people walking in the rain when a nearby volcano erupted three million years ago. When she revealed one of the finest footprints, Mary sat back and gazed at its beauty. She lit a cigar and said, “This is really a piece to be placed over the mantelpiece.“

Mary was 65 years old when she made this discovery. Mary continued her research in Laetoli and Olduvai until the late 1980s. When she died in 1996, Mary Leakey was the world’s most famous female archaeologist. Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey had achieved the goal they set before they set out on this African expedition. They had unearthed the evidence that the first ancient humans evolved in Africa. Like all great scientists, they shattered old ideas and ways of thinking – with stones and bones.

Bibliography:

- Mary Bowman-Kruhm, The Leakeys: a Biography, Greenwood Press, 2005. ISBN 0-313-32985-0

- Roger Lewin, “The Old Man of Olduvai Gorge”, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2002.

- For an account of the incident refer to Hans Reck and the Discovery of O.H.1 Archived 3 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine at the “Always Something New” site.

- The source for this subsection is Morell, Chapter 3, “Laying Claim to the Earliest Man”.

- “The Leakey Foundation”. The Leakey Foundation.