The Maginot Line was a system of fortifications built from 1928 to 1938, located on the northeast border of France. It is named after the Minister of War at the time, André Maginot, who had this defense project adopted by Parliament in 1930.

Following the trauma of World War I, the objective was to prevent a new German invasion and make the French territory impregnable. The Maginot Line became closely associated with the painful memory of the 1940 defeat. In the collective memory, it bears a significant responsibility, symbolizing the immobility, sclerosis, and archaism of the French army, strictly confined to a defensive strategy unsuitable for the realities of modern, fast-paced, and mobile warfare.

A Consequence of World War I

After the conclusion of World War I, France found it imperative to completely reassess its military strategy. The war experience marked a radical shift in warfare, with the emergence of aviation, armored forces, and the development of highly destructive artillery. The vulnerability of the traditional infantry became evident in the staggering losses suffered by the French army throughout the war. The previously untenable strategy of relentless offense, adopted by the French high command in 1914, needed reevaluation, paving the way for the formulation of a new strategy.

In the early 1920s, two rival doctrines emerged.

Marshal Foch advocated for the creation of a rapidly deployable mobile army, while Joffre and, particularly, Pétain argued that a continuous defensive front was invulnerable, forming the basis for France’s defense.

Additionally, the Treaty of Versailles returned Alsace and Lorraine to France. These newly acquired, richly populated territories necessitated inclusion in the new French defense policy. The existing line of forts from Montmédy to Belfort was inadequate for defending these territories in the event of a new war, a constant concern for the French high command.

World War I also led to a reevaluation of fortifications. The rapid fall of Belgian forts in August 1914 convinced the high command of the futility of such structures, leading to the disarmament of forts. The forts of Séré de Rivières, built in the 1880s, were scarcely used during the war’s initial phase. Troops moved forward beyond the forts, making them susceptible to quick capture by the Germans in the early days of the Battle of Verdun.

However, the Battle of Verdun played a pivotal role in the rehabilitation of fortifications. The resilience of Fort Vaux and the significant role of Fort Souville highlighted the utility of fortifications. Lessons from this battle were crucial in shaping future strategies. The new strategy became decidedly defensive, relying on massive fortifications housing effective artillery.

The construction of the new French fortifications adhered to principles such as protecting the Northeastern border facing Germany and the Southeastern border facing Italy. This involved establishing a continuous front and creating an uninterrupted line of fire along the fortifications. The backbone of the system comprised deeply entrenched fortified structures with dispersed organs and equipment, allowing crews to live and fight for months without external contact. The construction of this system was entrusted to the Commission de Défense du Territoire (CDT) and later to the Commission de Défense des Frontières (CDF) starting in 1922.

Construction of the Maginot Line

These two commissions would be tasked with defining the nature and layout of the new fortifications. However, it would not be their responsibility to implement the construction of the fortifications; they served as a reflective body where different concepts of fortification would be debated.

By the end of 1925, the Supreme War Council approved the commission’s report, envisioning the construction of a discontinuous fortification system, even during times of peace.

The project presented in November of the following year outlines the creation of three fortified regions—meaning three continuous lines of fortifications separated by non-fortified spaces, similar to Séré de Rivières’ fortified curtains—centered around Metz, the Lauter Valley, and Belfort, along with fortified positions behind the main ones.

This project was gradually streamlined, leading to the final 1929 plan that envisioned the creation of two fortified regions (Metz and Lauter), a specific defense line along the Rhine in Alsace, and the defensive organization of the Alps.

In 1927, the Commission for the Organization of Fortified Regions (CORF) was established. Its role was to implement the decisions of the CDF, and it became the primary architect of the Maginot Line. Comprising the best specialists from the three armed forces involved—artillery, infantry, and engineering—it was tasked with finalizing the positions’ layout, implementing construction projects, and managing equipment.

The CORF established regional delegations in Metz and Strasbourg, to which local engineering headquarters (Thionville, Bitche, Mulhouse, Belfort, and Nice, among others) are subordinate. The enormity of the task, the scale of the construction projects, the numerous technical challenges, and the overwhelming responsibility placed on the technicians and officers working on this colossal project necessitated the involvement of the country’s scientific and technical elite.

The next step was to gain approval for the project from political institutions. Early in 1929, the Council of Ministers approved the CORF’s project. When André Maginot succeeded Paul Painlevé as Minister of War at the end of 1929, he was tasked with taking over the dossier. He ensured the project’s approval in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, where it received over 90% of the votes.

On January 14, 1930, a law was passed allocating 2.9 billion francs over 5 years for the fortification projects. However, in reality, the work had already begun long before.

By the end of 1928, construction of the first structure of the Maginot Line, the Rimplas fortification in the Alps facing Italy, was underway, although the majority of the fortifications would later be oriented towards Germany.

Most of the major works in the Northeast were initiated in 1929. The blocks were cast and armed between 1929 and 1934. Most structures became operational by 1935, even though considerable work was still required to enhance the comfort inside the fortifications.

Simultaneously, hundreds of casemates and thousands of small bunkers were constructed according to the CORF’s plans, and millions of rails were planted to establish a massive anti-tank barrier along the northeastern border. By 1936, the core of the Maginot Line was constructed and operational, leading to the dissolution of the CORF. However, this did not mean that construction of the Maginot Line ceased entirely.

Budget and Technical Limitations

The budget consistently put pressure on the CORF (Commission d’Organisation des Régions Fortifiées) throughout the construction process, either due to unanticipated costs, particularly for specific circumstances requiring special arrangements, or as a result of the extremely high inflation during those years. For these reasons, the ambitions of the CORF had to be constantly scaled-down, leading to the abandonment of the construction of certain blocks, bunkers, or even entire structures, resulting in serious weaknesses in certain sectors.

The Faulquemont region and the border with Belgium from Longuyon to Willy were both fortified as part of a second phase of work that began in 1934 to equip certain sectors that the first phase had neglected. However, the structures built in this second period had a much lower budget and, consequently, were of much lower quality than those constructed in the previous period.

After the CORF’s mandate ended in 1936, the construction of the Maginot Line continued under the guidance of the Main-d’œuvre militaire (MOM) or the Service Technique du Génie (STG) of each region, following plans drawn by officers present on-site.

These late achievements suffered not only from a significant lack of resources but also from a blatant lack of coherence, as each sector followed plans drawn by officers whose tactics could differ radically from those of the neighboring sector. These isolated construction campaigns did not cease with the declaration of war and sometimes continued until June 1940. Alongside the actual construction, a campaign of technical innovation had to be launched to equip the new fortifications.

By 1936, France possessed a brand-new and seemingly invulnerable system of fortifications. The years that followed, especially with the outbreak of World War II, provided an opportunity for the Maginot Line to prove its qualities in battle. Indeed, the Maginot Line played a genuine strategic role in the campaign in France, a role often unknown to the general public today, even though the battles that took place there were of great intensity.

The Maginot Line in the War

The moment the large fortifications are put into service, they are occupied by specialized troops created for the occasion—fortress troops comprising detachments of infantry, artillery, and engineering. In times of peace, these troops are stationed in barracks behind the fortifications they occupy at the slightest alert. Thus, even before the declaration of war in September 1939, the Maginot Line would be put on alert several times based on the convulsions in Franco-German diplomatic relations, such as the remilitarization of the Rhineland in March 1936 or the Anschluss in March 1938. However, on August 23, 1939, when reservists were put on alert, the occupation became permanent.

During the fall and winter of 1939–1940, similar to the rest of the front, no notable events occurred on the Maginot Line except for a few skirmishes and aerial combats. Half of the French army—the 3rd, 5th, and 8th armies—massed behind the line and remained entirely passive during these nine months of the “Phoney War.”

On May 10, 1940, the German army launched its major offensive against Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and France. The French army stationed behind the Belgian border immediately moved to engage the Wehrmacht in Belgium, while the troops of the Maginot Line remained in their positions. In the initial days of the campaign, the battlefield remains distant from the Maginot Line.

The first significant contact between the German army and the fortifications of the Maginot Line occurred on May 16, 1940, at the Ferté outpost near Montmédy. It is a small and lower-quality outpost built in 1934, but it is the first Maginot Line outpost that the Germans had the opportunity to attack. They unleash a barrage of shells on the two casemates, overwhelming the modest outpost. Three days of incessant bombardment filled the interior with smoke, causing the asphyxiation and death of all 107 soldiers in the crew.

Apart from this tragic episode, the majority of the Maginot Line remains away from the main axes of the German offensive. Fearing the resistance of the fortifications, the Germans launched assaults against the line itself only very late in the campaign, coinciding with the beginning of the evacuation of Maginot Line troops after Weygand’s general retreat order on June 12. By this date, the French army is already defeated, and the Maginot Line troops are the only corps holding their positions with intact equipment.

However, when the Germans launched their first major offensive against the Maginot Line, most of its garrison troops were still in place. The Wehrmacht chooses to attack in the Sarre Valley, where the Maginot Line consists of small casemates and large artificial water bodies forming a defensive line. On June 14, 1940, after artillery and aviation bombardment, the Germans assaulted the fortified line.

Fierce fighting ensues throughout the day in the woods of the Sarre Valley. By evening, French troops, reinforced by some Polish units, managed to repel the Germans at the cost of 500 casualties. The Wehrmacht, on the other hand, suffered over 1,000 losses. Paradoxically, this became the greatest French victory of the 1940 campaign, achieved on the same day as the fall of Paris.

However, it is a victory without lasting impact. The Sarre troops, like the rest of the French army, must retreat, abandoning the positions they fiercely defended on June 14. The general retreat of all field troops leaves the Maginot Line with only 22,000 defenders, from Luxembourg to Switzerland.

From then on, the Germans exploited this breach in the Maginot Line to encircle it. Soon, most fortified outposts would find themselves attacked from all sides. On June 15, the German army launched an offensive on the corner of the Maginot Line in Lower Alsace.

For several days, the Germans attempted to breach the line of fortifications but failed.

On June 19, a new German attack was launched in the Vosges. The mountain range crest was defended only by a series of small casemates deprived of artillery support due to the withdrawal of field artillery. They could only resist fiercely before being taken.

On June 16, taking advantage of the French withdrawal in the Rhine Valley, the Germans launched a bold amphibious operation. In a state of significant numerical inferiority and almost without artillery support, the French could only delay the battle before gradually retreating. The fighting, however, continued until the armistice between France and Germany came into effect on June 22.

However, the battles are not confined to the Northeast. On June 10, 1940, Italy declared war on France and launched an offensive against the French fortifications in the Alps. Despite significant numerical superiority, the Italian advance was laborious and faced great difficulties, notably due to the effectiveness of the Maginot Line fortifications in the Alps.

After Armistice

When the armistice came into effect on June 24, 1940, the Maginot Line was largely intact. No major artillery fortifications had surrendered to the Germans. While a few casemates and small fortifications had fallen to the Wehrmacht from June 20 onwards, neither the artillery—the Germans utilized 420mm cannons—nor aerial bombardments succeeded in incapacitating the concrete and steel fortresses. When the fighting ceased, both adversaries faced each other, and the situation proved to be quite delicate to resolve.

According to the laws of war, as the troops of the Maginot Line were undefeated, they were entitled to withdraw without being imprisoned, a concession the Germans refused. The French negotiators at the armistice commission were compelled to yield.

For several days, a French military delegation bearing government orders toured all the Maginot Line fortifications to organize the surrender and captivity of all garrisons. On July 1, 1940, the 22,000 defenders of the Maginot Line abandoned their fortifications to surrender them to the Germans. Like two million French soldiers, they would endure nearly five years of captivity in Germany.

During the occupation, the Germans capitalized on the potential of the Maginot Line. Some fortifications were used to test new German weapons, while others became true underground war factories, sheltered from Allied bombardments.

As the prospect of an Allied attack on Europe became increasingly likely, the Germans conceived grand plans to repurpose the Maginot Line into a vast defensive line facing the West. The Germans had made no significant changes, however, when the Americans reached the back of the Maginot Line in October 1944.

In some areas, the Maginot Line impeded Allied progress, but it did not play a significant strategic role during this campaign. Before abandoning certain fortifications, the Germans sometimes carried out explosive demolitions.

Phased Abandonment of the Maginot Line

After the restoration of peace, the Maginot Line was not abandoned. It now plays a role in NATO’s strategy, considered a defensive line against a potential Soviet offensive in Western Europe. However, despite being at the forefront of military technology in 1939–1940, the Maginot Line is entirely obsolete in the face of new artillery and the realities of the Cold War and the atomic bomb era.

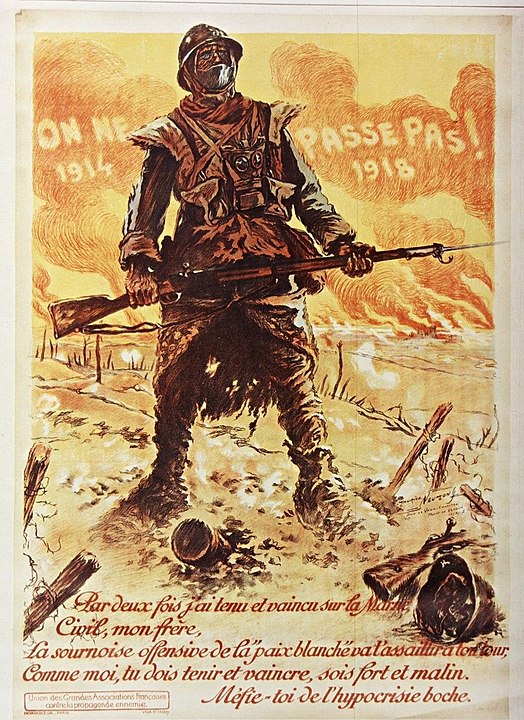

In the 1960s, the military gradually abandoned the Maginot Line. Many fortifications were simply left to decay and fall into oblivion. Some of them are still in use by the military, like the Hochwald fortification in Alsace, which currently houses one of Europe’s most significant radar bases. Others have been acquired by enthusiasts’ associations, restored, and opened to the public. It is now possible to visit some of these sites that played an important, albeit often overlooked, role during the 1940 campaign. The fortress troops ultimately lived up to the motto of their corps, “On ne passe pas!” (They shall not pass).

Featured Image: A5 Bois du Four Maginot Line, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0.