Who are the Mapuche people? When it comes to Native Americans and the Great Plains, most people think of the North American Great Plains during the pioneering era and the Sioux people riding on horses with tomahawks in hand. However, on the other side of the Americas, in the Pampas grassland region of South America, there were other native Americans—the Mapuche people, who are the most representative indigenous people of South America. The hero of the Mapuche people, Lautaro, played a crucial role in the Latin American independence movement. The Lautaro Lodge was named after him, which was a revolutionary secret lodge in the 19th century.

Origins of the Mapuche People

The ancestors of the Mapuche people were the Araucanians, who lived in the Andes Mountain region and were known for their bravery and martial skills during the Inca Empire period (1400–1533).

Since the discovery of the New World, the rulers of the central highlands of South America changed from the Incas to the Spanish conquerors, and the Araucanians naturally became the most troublesome indigenous people for the Spanish.

In the American-Indian Wars, which lasted for nearly 200 years, the Araucanians produced many heroes like Lautaro, who resisted the Spanish, but ultimately, they were forced to move south under Spanish pressure.

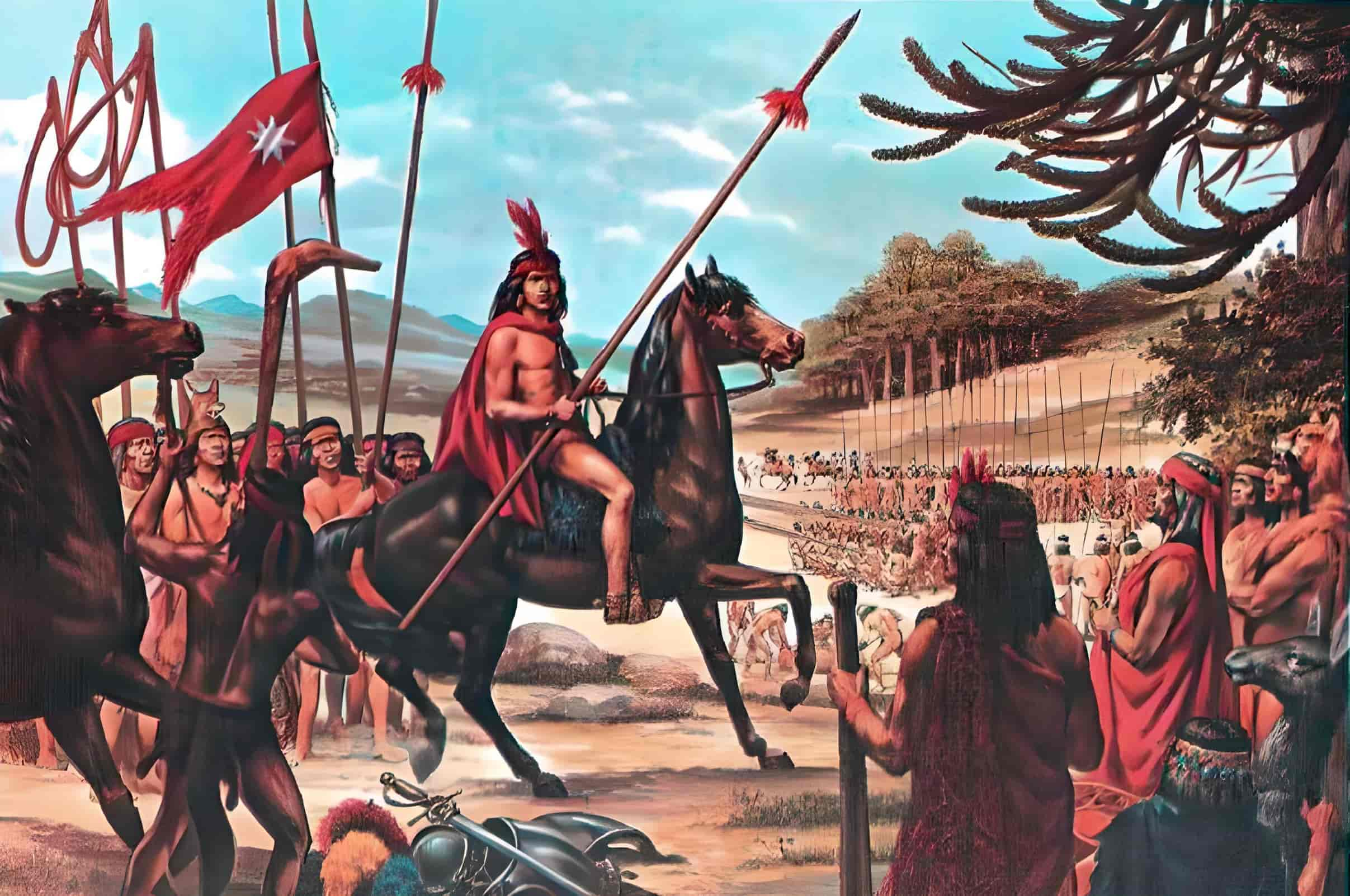

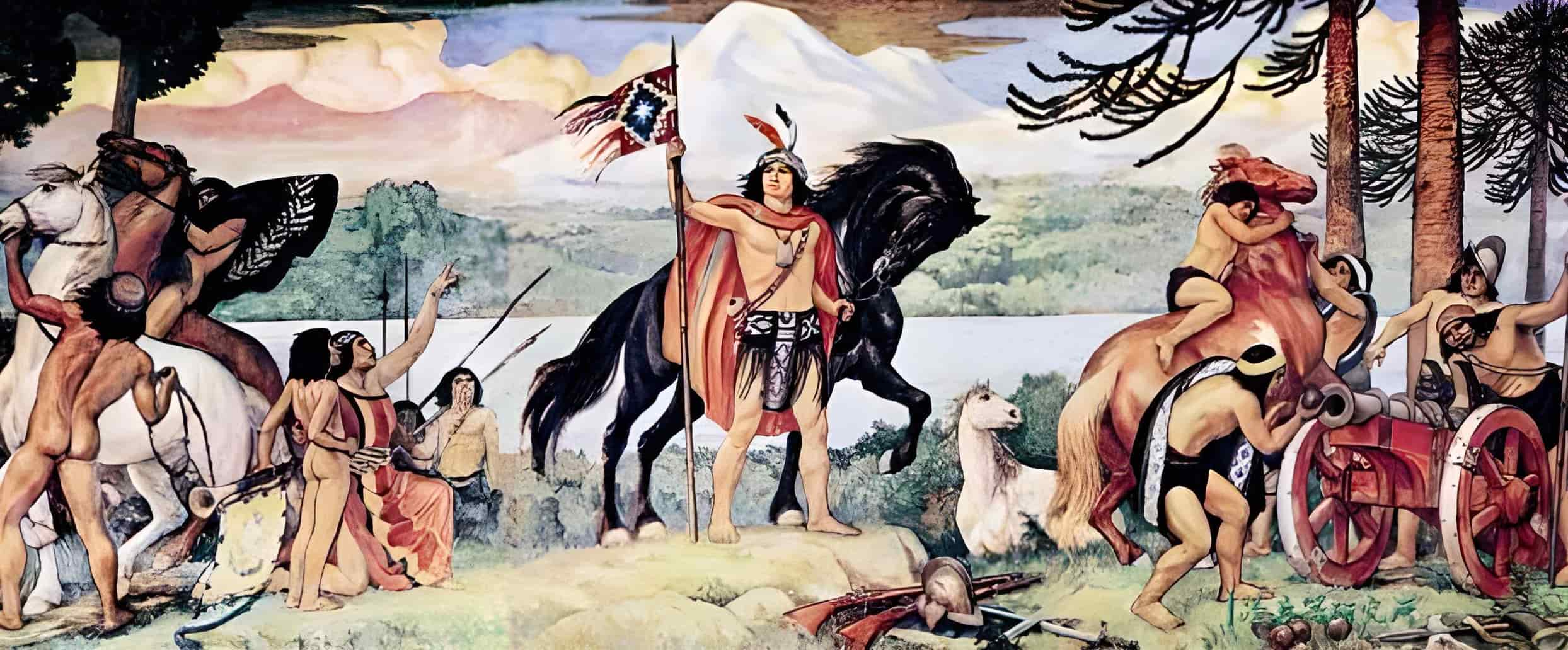

It was under Lautaro’s leadership that the Mapuche people were able to repel a Spanish invasion of Chile and ultimately execute the governor, Pedro de Valdivia, on December 25, 1553.

The Mapuche people originally lived in the forests of the southern Andes. In the 18th century, they arrived on the Pampas Steppe. It is located in southern South America, north of the Patagonian Desert, south of the Andes Mountains, and west of the Atlantic coast.

The word “pampa” means “plain” in Quechua, and it was named after the flat terrain. The entire grassland has a mild climate, abundant grass, and the La Plata River flowing through it, making it one of the world’s most suitable natural grazing areas.

History of Mapuche

During the Age of Exploration, the early Spanish colonizers were keen on plundering America’s gold and silver. But their attempts to establish colonies in the La Plata River basin failed.

However, the large number of livestock, such as horses and cattle, abandoned by the Spanish took root in the Pampas grassland and multiplied for generations, forming a massive herd in the grassland region.

After precious metals from South America began to run out, Spanish colonizers also recognized the value of the grassland.

Shepherds from Andalusia in Spain brought Iberian-style animal husbandry technology and crescent-shaped spears to the plains, gradually forming a unique American-style shepherd—the gaucho.

The indigenous South American people of the grasslands, who were originally in the gatherer stage, quickly transformed into nomads due to the introduction of the gaucho’s livestock-raising methods.

The bow and arrow were replaced by more convenient weapons such as bolas from the Incas and spears from Spanish shepherds, which could be easily used on horseback. The bolas were stone-slinging weapons.

The Pampas Turned Into Mapuche Territory

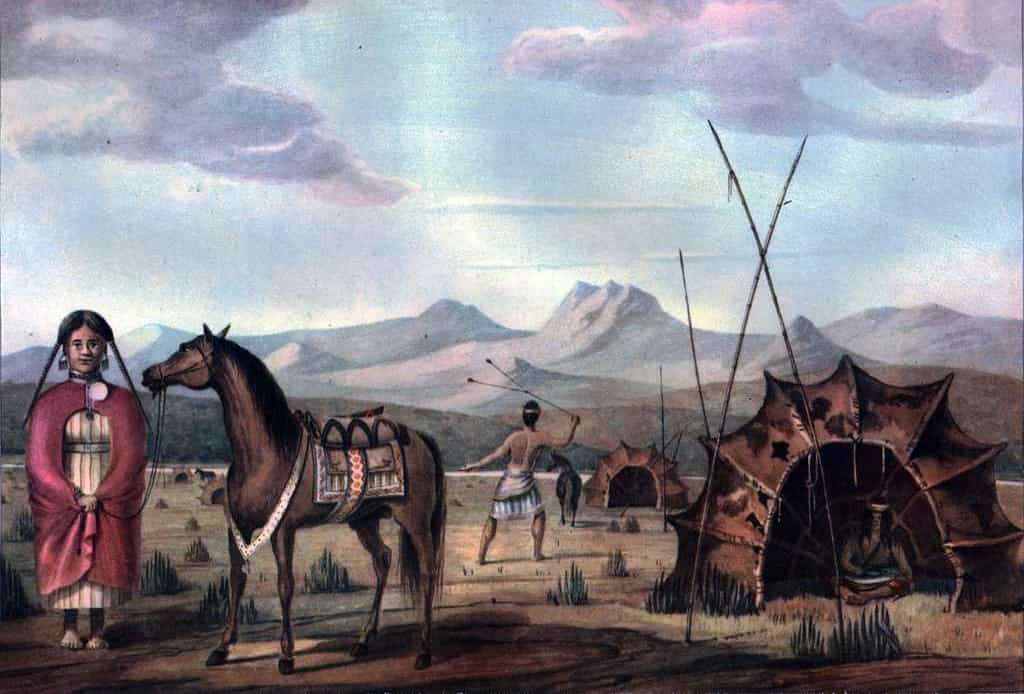

In 1708, the first group of Mapuche people arrived on the Pampas grasslands in search of trade opportunities for their horses. The Mapuche people’s martial prowess made them revered by the local indigenous people, and the abundance of resources and comfortable environment on the grasslands attracted even more Mapuche from Chile.

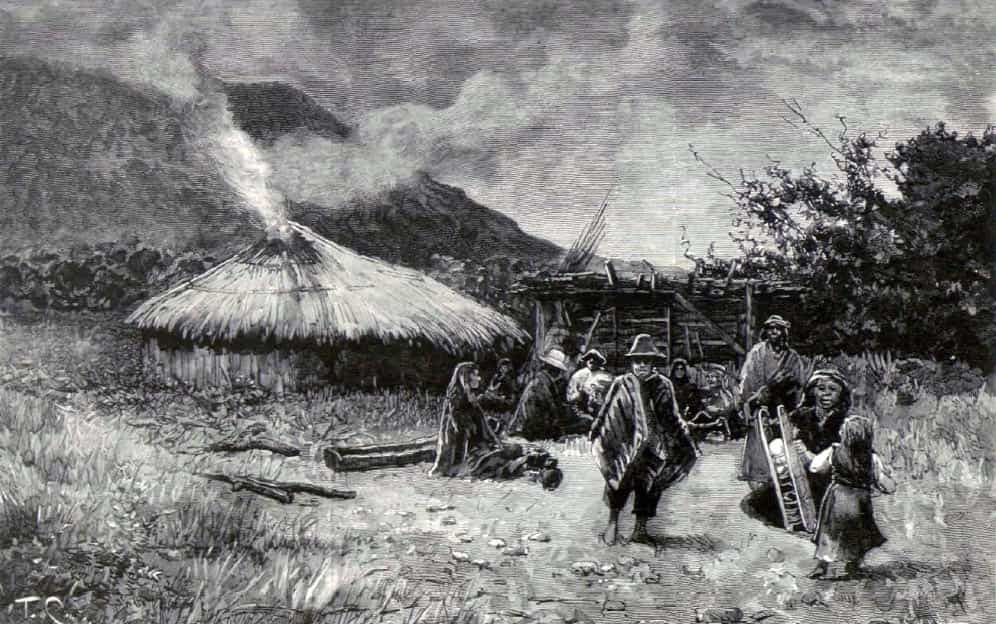

After arriving on the grasslands, the Mapuche gradually mixed with local indigenous tribes, intermarried with them, and abandoned their horticultural techniques from the Andean region in favor of the indigenous people’s livestock techniques, becoming pastoralists who lived in conical tents covered with animal hides.

The local indigenous people, in turn, adopted the Mapuche language, social customs, and rituals, establishing a warrior-centered society. Tribal leaders gained hereditary rights, and smaller tribes formed larger political alliances through closer cooperation.

This process was referred to by the Spanish as the Araucanization of the Pampas. By the 1770s, the Mapuche language had become the lingua franca of all indigenous people in the Pampas region, and the grasslands had become the Mapuche people’s domain.

Traditional Weapons of the Mapuche

Spears Were the Symbol of Power

During the long war with the Spanish, the Mapuche people assimilated many of the Spanish tactics, particularly those involving the use of spears. Even during the Araucanization period, spears had become the Mapuche people’s primary weapons.

On the Pampas grasslands, the Mapuche people became skilled in mounted combat, and their spears grew to around 10 feet (3 meters) in length, with spearheads made of metal seized from the colonizers.

The number of spears a tribe possessed became a measure of their strength, and spear duels were often used to settle conflicts between individuals. For the Mapuche, spears became symbols of power and honor, and even religious artifacts.

Heavy Clubs and Clava

In addition to the spear, the Mapuche people often used the traditional weapon of their ancestors, the heavy club of the Araucanians.

The heavy club was typically about 6–9 feet (1.8–2.7 m) long and made of hardwood. For the Mapuche infantry, who did not use spears while on foot, the heavy club was a very advantageous weapon.

According to Spanish records, the Mapuche heavy club was highly effective against both horses and armored opponents. Their other traditional weapon was called the clava hand-club, and clava means club in Spanish. This polished stone hand club was also known as a clava mere okewa.

Mapuche Bow, Sticks, and Bola

The Mapuche people also commonly used bows, stone slings (bolas), and short sticks. The Mapuche bow was made from a mountain laurel tree, and the bowstring was made from the tendons of llamas. The bow was about 3.3 feet (1 m) long, and the arrow was about 20 inches (50 cm) long.

However, after the Mapuche people arrived in the Pampas grasslands, the bow was rarely used. The bolas sling was typically made from two or three stone balls tied together with a long rope.

This Inca traditional weapon became a useful tool for catching running livestock in the Pampas grassland region. In battle, Mapuche warriors used the bolas to entangle the legs of their opponents or their horses, rendering them powerless.

The War Between the Mapuche and the Spanish Colonizers

The Pampas grassland, which was transformed by the Araucanian culture, gave rise to powerful hereditary leaders who led large groups of spear-wielding cavalry to attack Spanish settlements, forcing the Spanish to establish long defensive lines in border areas.

As a result, the region south of the Buenos Ayres province remained unconquered by Spanish colonizers.

The Mapuche people raided Spanish strongholds in the past. In the 19th century, the Latin American region gained independence and was ruled by the descendants of the former conquerors, the Criollos.

They are people of Spanish descent born in the colonies. The indigenous people of this land, the Native Americans, remained oppressed. The newly formed country of Argentina began expanding southward.

Mapuche Were Finally Suppressed

However, the resilient Mapuche people were eventually defeated by the Argentineans, who possessed superior technology. Like the Native American conquest wars in North America, the railway eventually ensured the conquerors’ occupation of the land. Many Mapuche people were killed or driven back to Chile.

In 1884, the Conquest of the Desert (1870s–1884) war ended, and Chile and Argentina gained complete control over the southern region of South America. During this war, the Mapuches were led by Manuel Namuncurá.

Nevertheless, the Mapuche people of Chile and Argentina still retain their distinctive ethnic characteristics and regularly hold events to commemorate this last conquered Native American nation. During the parades and festivals, the spear is still a central focus of Mapuche.

The traditional Mapuche homeland is now an integral component of Chile. The Mapuche people participated in one of the longest wars in human history, lasting somewhere around 330 to 340 years and resulting in the deaths of over 200,000 individuals.

Chemamüll, Mapuche Funeral Statues

Chemamülls (which mean “wooden figures, “che” for figure, and “mamüll” for wood) are wooden statues created by the Mapuche people. They serve as grave markers for the deceased.

These statues, standing over 6 feet tall, depict a stylized human body and head and can be made from whole logs of hardwood or laurel.

They were used in pre-Columbian times as a form of headstone and were believed to aid the soul of the deceased in reuniting with their ancestors. After being present during the funeral, the chemamüll would be placed over the grave.

References

- George v Rauch. 2000. The Argentine Military and the Boundary Dispute with Chile. Google Books.

- Diego Rey, Carlos Parga-Lozano and others: “HLA genetic profile of Mapuche (Araucanian) Amerindians from Chile“. Molecular Biology Reports.

- Erika Wittekind. 2011. Argentina: Countries of the World.