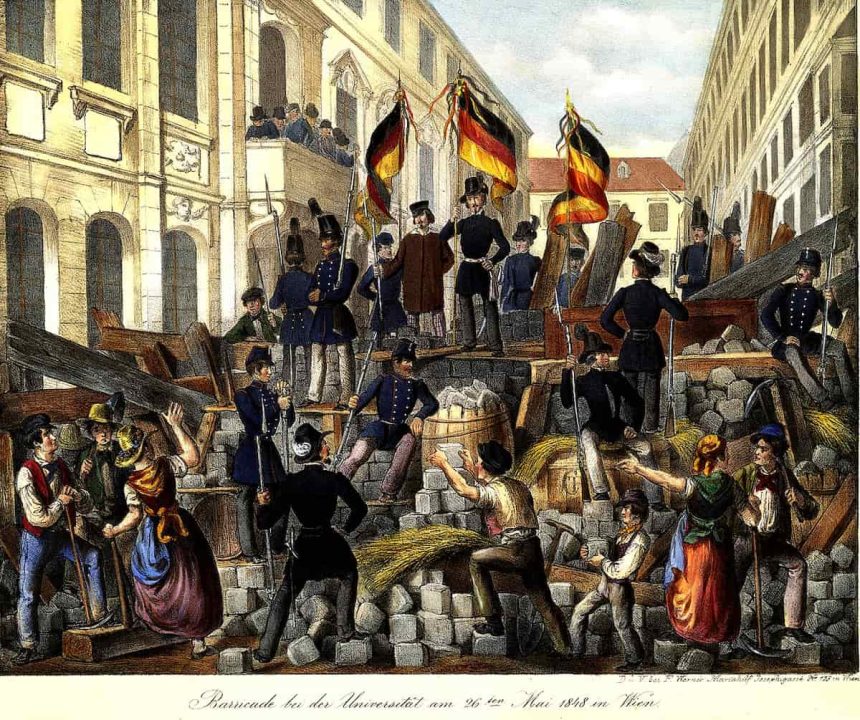

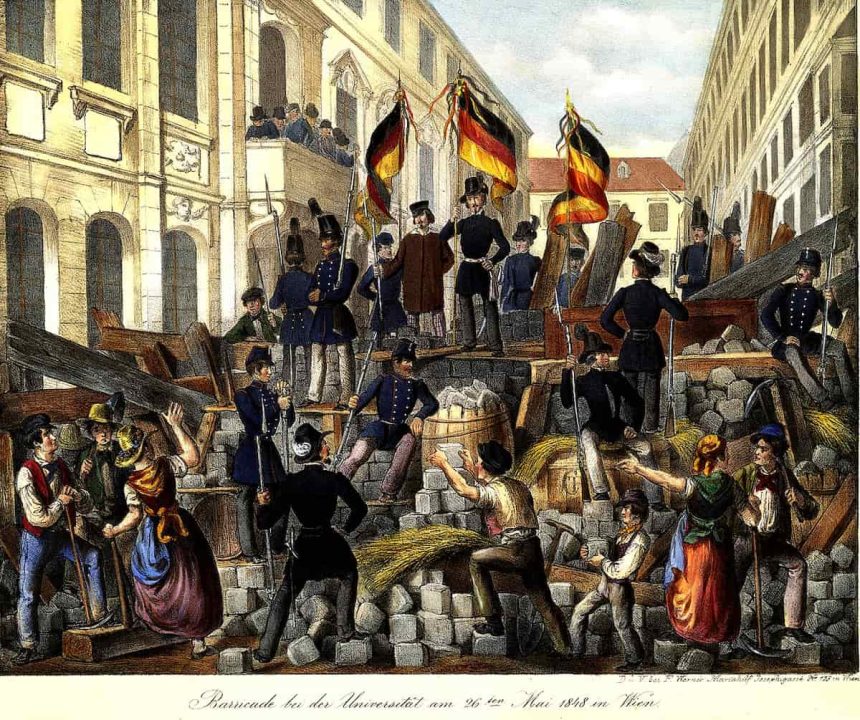

People’s Spring: Summary of the March 1848 Revolution

The revolution of 1848 was marked by popular uprisings in Italy and Germany, inspired by those that had begun in France and Switzerland a few months earlier: the People's Spring.

The revolution of 1848 was marked by popular uprisings in Italy and Germany, inspired by those that had begun in France and Switzerland a few months earlier: the People's Spring.