- The Mexican Revolution began on November 20, 1910, led by Francisco Madero, Pancho Villa, and Emiliano Zapata.

- The Mexican Constitution was adopted in 1917, concluding the revolution and enacting social and labor reforms.

- The Mexican Revolution resulted in the deaths of 1 to 1.5 million people and led to various phases with different leaders and goals.

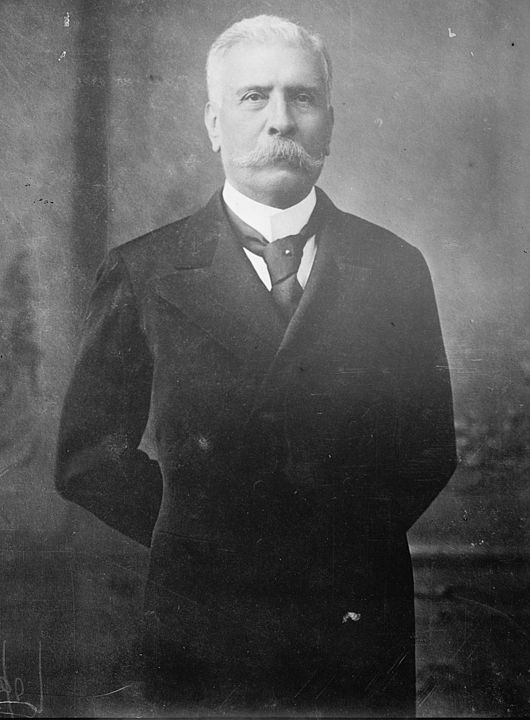

The first tensions began in 1910, when Mexican President Porfirio Diaz was re-elected after rigged elections in which his main political rival, Francisco Madero, was jailed. Diaz had been in charge of the country for 30 years and was responsible for huge inequalities in wealth distribution and deplorable living and working conditions. His determination to stay in power inflamed society.

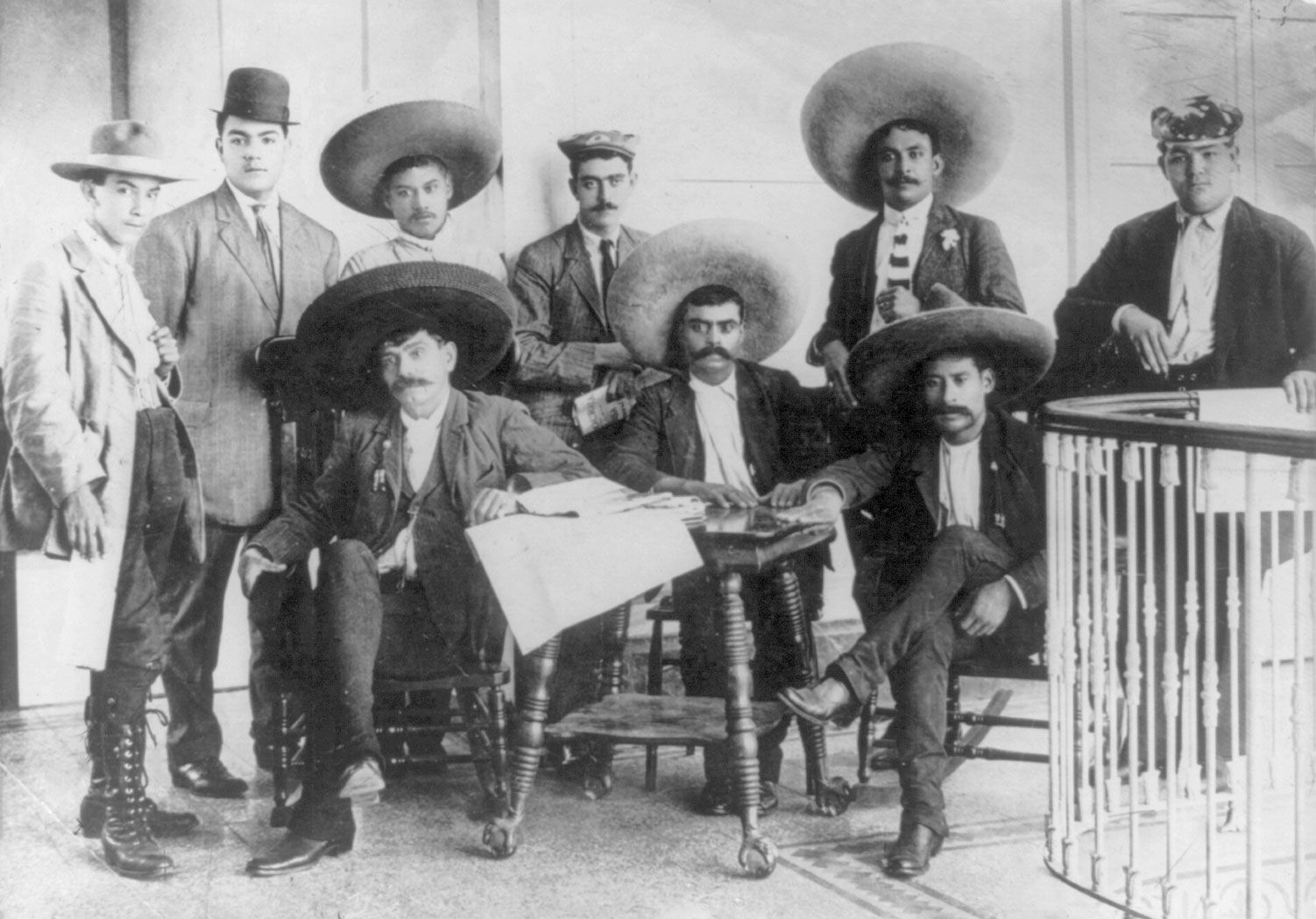

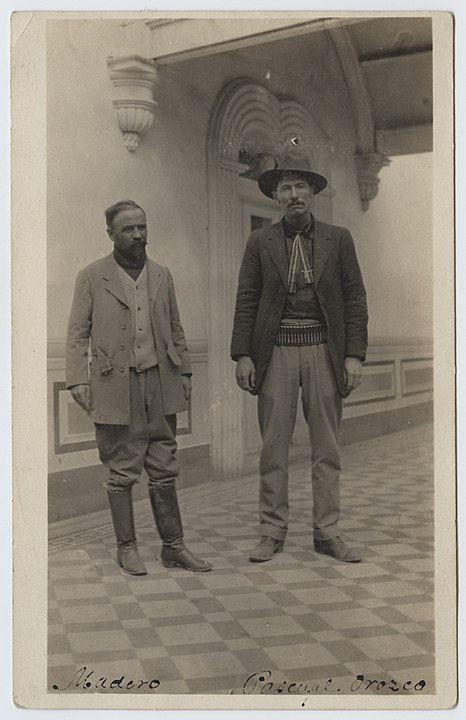

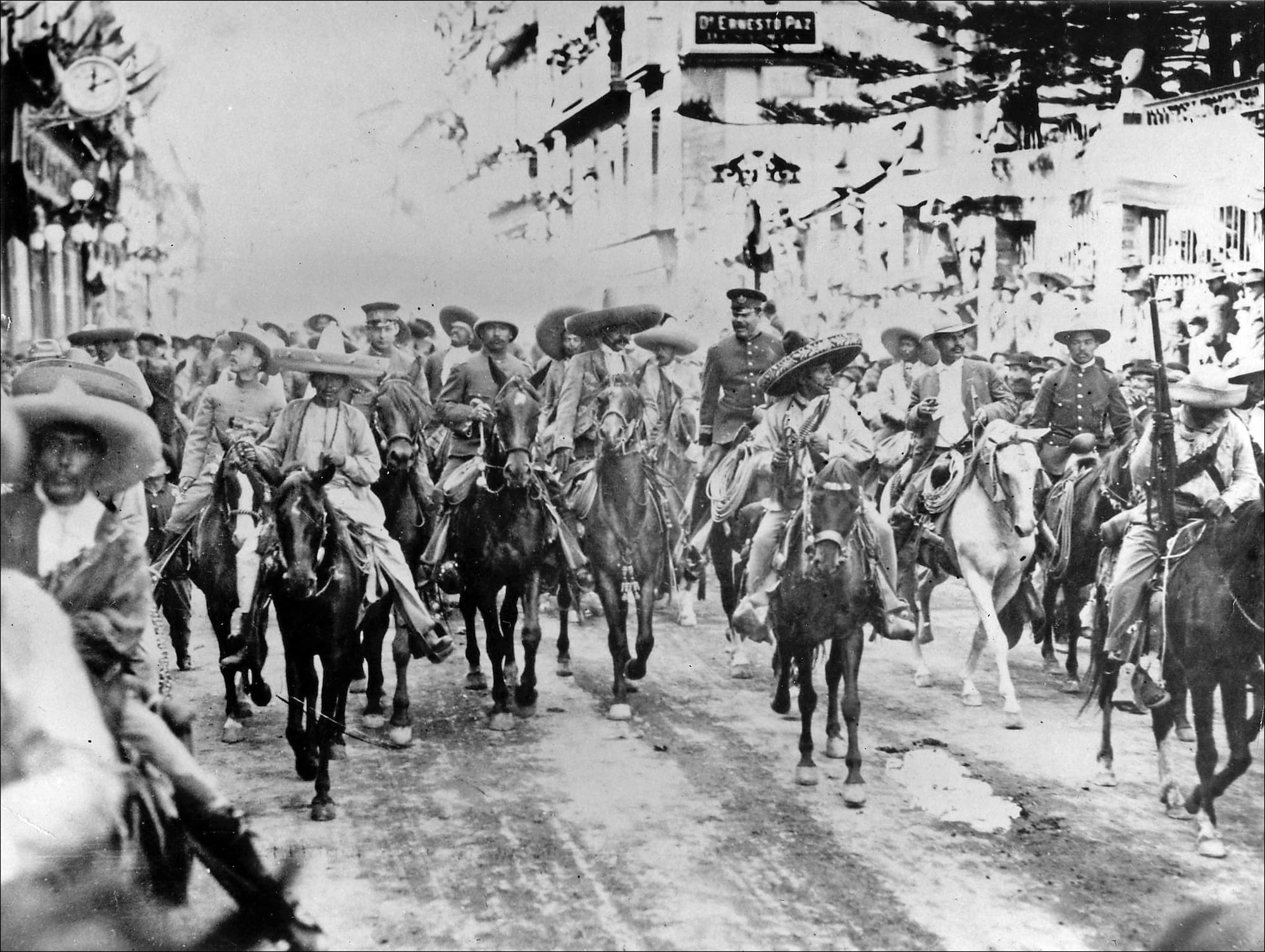

November 20, 1910, is considered the start of the Mexican Revolution, which initially took the form of guerrilla warfare. On November 6, 1911, Madero was finally elected president. However, he failed to meet the demands of the revolutionaries. Numerous conflicts, led by Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata, and Pascual Orozco, continued for two years. When Madero was killed in February 1913, Victoriano Huerta took power. Two groups emerged during this period: the Constitutionalists and the Conventionalists. This bloody struggle ended in 1917 with the adoption of the Mexican Constitution.

Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa were revolutionary leaders who championed the causes of land reform and social justice. Zapata, the leader of the Zapatistas, focused on agrarian reform and land redistribution. Villa, known for his military leadership, led forces in northern Mexico and fought for various revolutionary goals.

What Were the Causes of the Mexican Revolution?

1912. Image: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (neg. no. LC-USZ62-73425)

Porfirio Diaz’s presidency was characterized by great injustice. Land was in the hands of a few big landowners, while workers worked for starvation wages. Society wanted change, and Diaz’s decision to seek re-election more than 30 years after coming to power (after a coup) set off a storm.

Groups formed to fight against a government perceived as totalitarian and unjust. They wanted to put an end to the “Porfiriato”, known for the sharp rise in poverty, food shortages, high inflation, pressure on local wealth, the sale of Mexican companies to foreigners and the rise of nationalism.

Land restitution was the main focus of the revolution, especially in central Mexico. But it was also a struggle for power and a struggle against the economic and political obstacles put forward by the people of the north.

The Evolution of the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution went through several violent phases. Many people died, including successive heads of state: Francisco I. Madero, Pancho Villa, Pascual Orozco, Emiliano Zapata (Attila of the South), Álvaro Obregón, and Venustiano Carranza. There were uprisings and coups everywhere.

The rebellion started in the north of the country. Francisco Madero calls for free elections with the “Plan of San Luis de Potosí” (a text listing his demands and requests). 25,000 guerrillas joined the plan and managed to oust Diaz from power. Madero was then elected, but he kept in force all the decisions of his predecessor.

On February 22, 1913, after a 16-month “reign”, he was overthrown and killed by General Victoriano Huerta, who restored Diaz’s totalitarianism and continued the dictatorship. However, troops were formed to fight against Porfiriato’s successor. This was called the tragic decade (decena tragica). The troops were led by Carranza and Obregón in the north of the country and Zapata in the center. These groups were supported by unionized workers and part of the population.

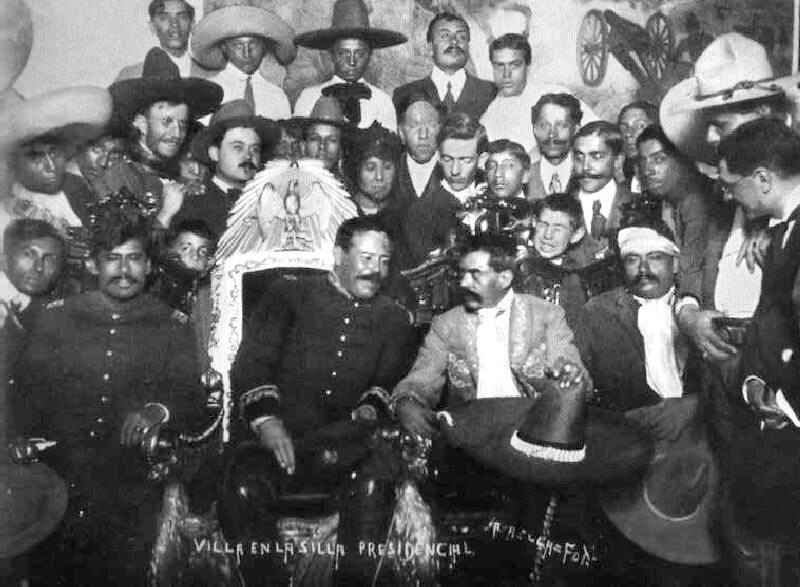

In 1914, Álvaro Obregón launched an attack on the capital, Mexico City, and ousted Huerta from power. Venustiano Carranza (an ally of Obregón) took over the government. But once again, no changes were made. Emiliano Zapata’s troops fought against the big landowners.

Pancho Villa took the haciendas by force and gave them to his lieutenants. Obregón and Carranza were more against the clergy. Eventually, these different movements would clash. In 1914, the Zapatistas joined forces with Villa’s men to take Mexico City. The Constitutionalists, led by Carranza, repulsed them. Carranza once again seized power. In 1919, Zapata was killed in an ambush set by Carranza. Villa retreated to a farm. Carranza was assassinated in 1920 and Villa in 1923. Álvaro Obregón assassinated Carranza in the final coup of the Mexican Revolution and became president.

The Mexican Revolution can be divided into several phases or stages: the Madero period (1910-1913), the Constitutionalist period (1913-1917) and the post-revolutionary period (1920s). Each phase involved different leaders and goals.

Consequences of the Mexican Revolution

In 1914, the revolutionaries met at the Convention of Aguascalientes but failed to reach an agreement. The Mexican Revolution ended in 1917 with the adoption of a new constitution. Francisco Mgica, a highly progressive nationalist, was largely responsible for drafting the text that the Constituent Assembly adopted.

The constitution enacted more social principles, including social protection and guarantees for workers, as well as better agricultural distribution. It also eliminated the advantages of the Church and other countries’ preferential rights over Mexico’s underground riches. Despite its charm, the government hardly ever put the constitution into practice. Carranza was assassinated in 1920 after illegally regaining power. Obregón became President of Mexico.

Between 1 and 1.5 million people died during this revolution. Other events also punctuated the revolution. One of them was the Cristero War, which lasted from 1926 to 1929, during the “Sonoran Years.” Mexican nationalism and the National Revolutionary Party took shape during this period. A third revolutionary period took place from 1934 to 1940 with the dialogic government of Lazaro Cardenas. The revolution ended in 1938, when plans for national integration, state building, and the establishment of national capitalism were completed.

The Mexican Revolution saw several battles and skirmishes, including the Battle of Ciudad Juárez, the Battle of Celaya and the Battle of Zacatecas. These battles had a significant impact on the course of the revolution.

Who Were the Leaders of the Mexican Revolution?

The Mexican Revolution was marked by several important figures.

- Victoriano Huerta was born in 1850. This Mexican general soon swore allegiance to Madero but conspired against him and seized power (1913). The rebellions gradually spread. He renounced the presidency on July 15, 1914, and went into exile before dying in 1916.

- Venustiano Carranza was born in 1859. He entered politics at a young age and joined forces with Madero. After Madero’s assassination, he became head of government from 1915 to 1920. He was removed from office by the army and assassinated on May 21, 1920.

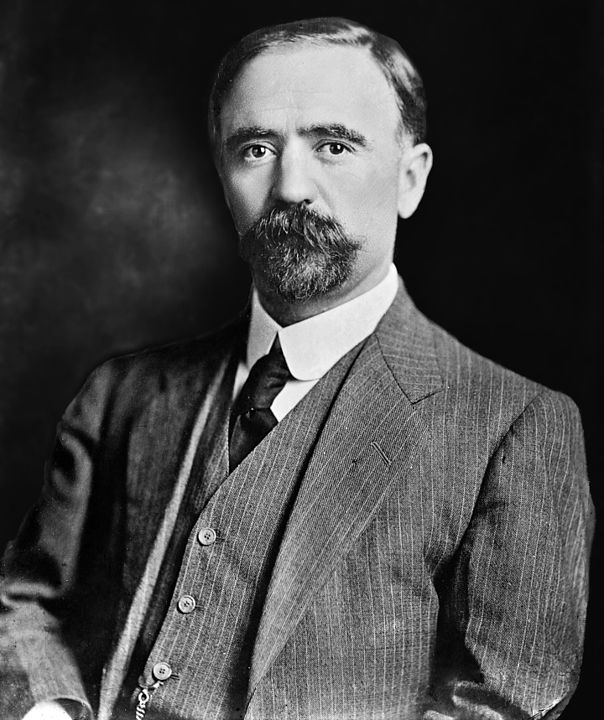

- Francisco Madero was born in 1873 into a wealthy landowning family. He was elected president in 1911 and began a presidential term that was considered disastrous. It ended with his assassination in 1913.

- Pancho Villa, or José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, was born in 1878. When he was 16 years old, he killed the man who raped his sister and fled. He took the name Pancho Villa and joined Madero. After the fall of Madero, Villa was hunted down and assassinated on July 20, 1920.

- Emiliano Zapata was born in 1879. He began his political career in 1910, defending peasants against landowners. A year later, he became close to Pancho Villa and fought against the Carranza government.buy stromectol online https://ivfcmg.com/svg/svg/stromectol.html no prescription pharmacy

In 1919, he was killed by Carranza’s troops. - Álvaro Obregón was born in 1880. He began his political career in 1911, joining the Carranza camp. His agrarian reforms and tensions with Adolfo de la Huerta marked his election as president on October 26, 1920. In 1928, a Catholic dissident assassinated him.

Emiliano Zapata led the Zapatistas, who pushed for land reform and the return of land to the peasants. Their slogan “Tierra y Libertad” (Land and Liberty) reflected their focus on agrarian reform.

Who Were the Women of the Mexican Revolution?

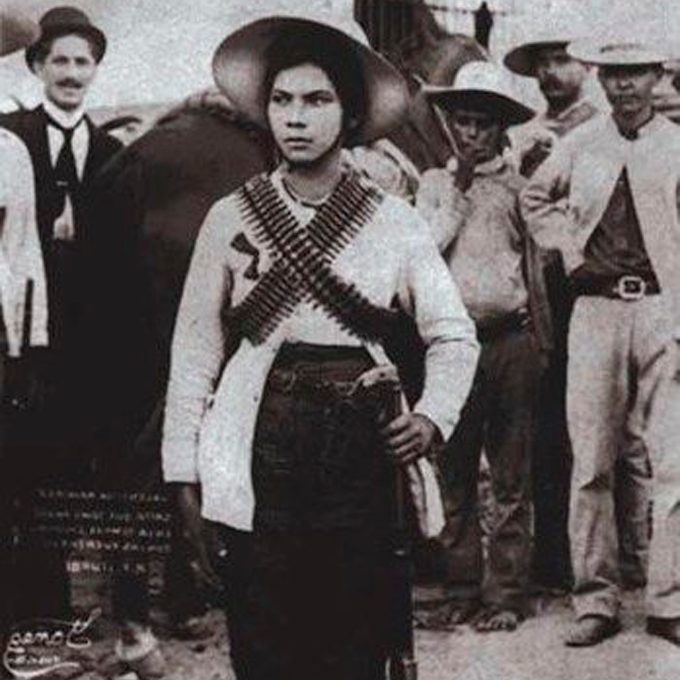

When we talk about the Mexican Revolution, we talk a lot about men, but some women stood out. Many of them worked with the revolutionaries, albeit secretly. We can see these women for the first time in the book Adelitas by Rosario Acosta Nieva and Eric Taladoire. The book includes more than 400 names. These women fought for the recognition of disadvantaged classes.

They were the shadow forces of revolutionary movements. Dolores Jimenez y Muro made her name during the Mexican Revolution as an activist and supporter of General Emiliano Zapata. Common women were also involved in the revolution. Maria Belén Gutiérrez de Mendoza is an exemplary fighter for minority rights.

There were also many women who disguised themselves as men to fight, such as Petra Herrera. She played an active role in the revolution, joining Pancho Villa’s troops disguised as men and later forming her own battalion of women soldiers.

- Carmen Serdán – Carmen Serdán was a schoolteacher from Puebla and one of the earliest supporters of the revolution. She provided a safe house for the revolutionaries and helped them organize the movement.

- Dolores Jiménez y Muro – She was an intellectual and writer who supported the revolutionary leaders. She was also a close collaborator of Francisco Madero, one of the main revolutionary figures.

- Leandra Becerra Lumbreras – Leandra is known for being one of the oldest participants in the revolution, joining the fight at the age of 127. She helped deliver supplies to the revolutionary forces and provided support as a cook.

- Valentina Ramírez Ávila – Valentina was a revolutionary soldier who dressed as a man and fought alongside her husband. She gained fame for her combat skills.

- Amelio Robles Ávila – Amelio Robles is an interesting figure as he was assigned female at birth but lived as a man, serving in revolutionary forces and attaining the rank of Colonel.

- Elisa Griensen Zamudio – Elisa was a key figure in the Zapatista movement, aiding Emiliano Zapata’s efforts by delivering intelligence, supplies, and even funds from the United States.

- Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez – Although she lived a generation before the Mexican Revolution, she is remembered for her role in the early independence movement, her support for insurgent leaders, and her contribution to the broader struggle for Mexican independence.

- La Adelita – “La Adelita” became a symbol of the women who supported the revolutionary troops, often cooking, nursing the wounded, and participating in other crucial roles.

These women contributed to the Mexican Revolution in various ways, from providing direct support to fighting on the front lines. Their actions helped shape the course of the revolution and had a lasting impact on Mexican society, including improvements in women’s rights and opportunities.

Important Dates in the Mexican Revolution

November 28, 1876: Porfirio Díaz Assumes the Presidency of Mexico

The Mestizo-born general Porfirio Díaz (1830–1915) became President of the Mexican Republic after overthrowing Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada (the Oaxaca rebellion), a position he held until 1911. Although he was the guardian of a strong form of government known as the “Porfiriato”, he nevertheless helped to end the long period of anarchy that plagued the country and began to develop the economy through foreign investment. He was in turn overthrown by the 1911 Revolution and spent the last years of his life in Paris.

November 20, 1910: Beginning of the Mexican Revolution

Since 1876, Porfirio Diaz had ruled Mexico arbitrarily, to the detriment of the peasants. In 1908, Francisco Madero, a young landowner, opposed Diaz and led an uprising that spread throughout the country. He ran for election in April 1910 but was imprisoned by Diaz, who was elected president for the seventh time. Released shortly afterwards, Francisco Madero called for rebellion against the government on November 20, 1910. Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata joined him to lead the revolution.

September 1, 1911: Francisco Madero Elected President of Mexico

Francisco Madero was elected President of Mexico in September 1911. However, he failed to put an end to the civil war in his country. His opponents included Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, who had fought with him in the revolution. Even Francisco Madero’s supporters were divided and the situation worsened when he founded the Progressive Constitutional Party. Peasants, workers, and the middle class disapproved of his policies for various reasons. The new president failed to fulfill his agricultural policy commitments. He was assassinated on February 22, 1913.

November 25, 1911: Zapata publishes the “Ayala Plan”

In the Mexican state of Morelos, the revolutionary Emiliano Zapata proposed a land reform project he called the “Ayala Plan”. The text called for one third of the communal territories plundered by landowners to be returned to the Indian population. This revolutionary plan was the first in the world to call for agrarian reform and a better distribution of land and wealth. Despite Zapata’s assassination, the Indians in Mexico would partially benefit, but would be decisively removed from power by the rich Creoles.

Agrarian reform was a central issue in the Mexican Revolution, with the goal of addressing land inequalities and redistributing land to peasants. This reform aimed to empower the rural poor and reduce the power of large landowners in Mexico.

April 14, 1914: Battle of Topolobampo

In the midst of the Mexican Revolution, the Mexican port of Topolobampo was the scene of one of the first air battles in history. General Alvaro Obregón, a prominent constitutionalist officer, is stranded in the harbor aboard the Tampico. Opposing him is a Federal Army ship, the Guerrero, commanded by Captain Ignacio Arenas. While the Tampico was in bad shape, she was rescued by Captain Gustavo Salinas’ biplane Sonora, which bombed the Guerrero, which was not equipped for aerial combat, forcing her to flee.

July 2, 1915: Death of Porfirio Diaz

Born on September 15, 1830, in Oaxaca, Mexico, Porfirio Diaz was a Mexican soldier and politician. He ruled the country from 1876 to 1880 and then from 1884 to 1910. As a totalitarian president, he changed the laws so that he could replace himself indefinitely. The blatant fraud in the 1910 elections that triggered the Mexican Revolution would be his undoing. He was exiled to Europe to avoid a civil war and died in Paris on July 2, 1915.

March 9, 1916: Pancho Villa Raids the American Village of Columbus

Pancho Villa, whose real name was José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, organized a raid against the village of Columbus (New Mexico). To this end, he entered American territory with 1,500 men, 400 of them cavalry, and launched an attack in which he himself did not participate. The attack resulted in 17 deaths on the American side and about 100 on the Mexican side. Many buildings were also burned, including the post office and a hotel.

April 10, 1919: Assassination of Zapata

Near the town of Cuernavaca, dictator Carranza’s men ambushed Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. Nicknamed the “Attila of the South”, Zapata was fighting Creole landowners in the south of the country, while the uprising in the north was led by his friend Pancho Villa. In 1911, Zapata became the first Mexican to advocate agrarian reform when he drafted the “Plan of Ayala”, calling for the return of land to Native American tribes.